I. INTRODUCTION

"Caesar's

son [Octavian/ Augustus], born Gaius Octavius and adopted in his will, avenged

his father's murder and liberated the republic, as he put it, `from the

domination of a faction´. Fourteen years later [30 BC], when his army entered

Alexandria, he not only ended the civil wars but took over the last and richest

of the Hellenistic kingdoms, thus giving

himself the means to fund what everyone longed for - peace, prosperity and the

rule of law" (my italics).

T.P. Wiseman[1]

This research

was inspired by a talk recently delivered by Bernard Frischer in Munich[2]. As a result of the

discussion after Frischer's talk and subsequent email-correspondence, Frischer

invited me to collaborate in a multi-authored article on the subject: "New

Light on the Relationship between the Montecitorio Obelisk and Ara Pacis of

Augustus"[3].

I happily agreed, and as a result of this, I had the chance to see Frischer's

own contributions to this article, as well as those of his other co-authors,

all of whom have opened up a wide spectrum of information and ideas that were

previously unknown to me; all those texts and images were at that stage almost

ready to print. I could thus sharpen some of my own ideas concerning Augustus

which I have already published elsewhere and that I will summarize below. As an

introduction to this text, I have deliberately used parts of an email written

to Frischer after his talk in which was summarized what I had said in the very

lively discussion after his talk[4], referring back to those

initial ideas in the following chapters and Appendices, adding some later own

findings, as well as observations that I made by reading the texts of other

authors. After completing my research I read T.P. Wiseman's new book, from

which the passage above is quoted. Interestingly, my study could be seen as

illustrative of Wiseman's interpretation of the historical significance of

Augustus.

Since my husband

Franz Xaver Schütz and I are ourselves likewise dealing with computer

reconstructions of ancient Rome[5], I believe to understand

what Bernard Frischer with the simulation of the Campus Martius presented in his talk is providing the scholarly

community with: a computer-based tool that is generated in a way which allows

to perform three operations more easily than by applying paper-based methods:

1.) tests of other scholarly opinions concerning this subject, 2.) own

reconstructions of the overall design(s) of the buildings in question in their

topographical setting(s), and 3.) the creation of visualizations of ideas

concerning the meanings of these buildings in their relevant environment(s).

Using this simulation, everyone

33

who has access to it, and is authorized to

change the relevant data, can for example test, how the position of the

obelisk, its orientation and height, and how the position of the Ara Pacis, its

position, orientation and height determine the effects that the sun itself and

the shadow(s) cast by the obelisk produce over the year.

There are, of

course, many things that we do not

know and which therefore prevent us from coming in many points to really

certain conclusions. For example: are the Meridian line with its Montecitorio

Obelisk and the Ara Pacis really related in the way that Edmund Buchner was

first to suggest? Or: why are the Obelisk and the Ara Pacis oriented in the

unusual way they are? By using simulations as the one developed by Frischer we

have a better chance to come to educated guesses, why Augustus and his

collaborators came to certain decisions concerning these buildings.

In one respect

I have to take back what I said in the discussion after Frischer's talk.

Considering the great efforts that Augustus undertook: bringing to Rome a

monolithic Aswan rose granite obelisk weighing ca. 214 tons all the way from

Heliopolis in Egypt[6],

in its Augustan installation ca. 29,6/ 30,0 m to 30,7 m high[7] including its base and a

"gilded bronze globe-and-spike finial"[8], plus erecting it (!) on a

huge square in the Campus Martius - I

(thought and) said in my ignorance: then Augustus and his collaborators were

crossing fingers that it would cast a `significant´ shadow on a certain day or

days, and came to the conclusion that this scenario calls for a mock-up,

thinking of a wooden dummy of the

obelisk[9]. Only after reading

Michael

34

Schütz's[10]

recent article on gnomonics, I understood that in the Augustan period

astronomers were in theory capable of calculating the shadows of gnomons

perfectly well (to the shadows cast by the Montecitorio Obelisk and to

astronomers I will return below).

Thinking of the

spectacular occasion, when the emperor Claudius ordered the finishing moment of

the digging of the emissarium

(`outlet´) of the Fucine Lake to be watched by himself, his wife Agrippina minor and invited guests - a work in

progress, that, inter alia because it

was ambitiously styled as an event, unfortunately went wrong[11], opens up another

question: was the entire project discussed here officially inaugurated in an

event, and if so, when?

As observed by

many scholars, the erection of the Obelisk/ Meridian was, of course, and

certainly not by chance, not only typical for an emperor in his capacity as

Pontifex Maximus, but also an immense contribution to the public good[12] - like Claudius' emissarium of the Fucine Lake.

35

Fig. 1.1. The Montecitorio Obelisk

seen from north (also called `Campus

Martius obelisk´ and `Campense´). In 1792 it was re-erected in front of the

Palazzo Montecitorio in Rome, today in use by the Italian Parliament. Augustus

brought this obelisk from Heliopolis in Egypt to Rome and placed it on the Campus Martius. In the foreground is

visible part of its modern meridian line (installed in 1998). Note the `gnomon

hole´ (light shaft) in the modern globe, which was set on top of the Obelisk.

Cf. ns. 7, 21, 26, 46, 48, 94, 141, 168-179, 185, 193, 200, and chapters

Domitian's Obelisk, the Obeliscus Pamphilius,

Appendix 1, Appendix 2, Appendix 4, Appendix 6, Appendix 10, Appendix 11, VIII.

EPILOGUE, Fig.

3.7, labels: Piazza di Montecitorio; Montecitorio Obelisk; Fig. 10.1 (photo: F.X. Schütz September 2015).

36

Fig.

1.2. The obelisk standing on the Piazza del Popolo in Rome, also called

`Flaminio´. Augustus brought this obelisk from Heliopolis in Egypt to Rome and

erected it on the spina of the Circus

Maximus; cf. chapters Domitian's Obelisk, the Obeliscus Pamphilius, Appendix 4,

Appendix 10, VIII. EPILOGUE, Fig. 3.5, label: Piazza del Popolo

Obelisk (photo: F.X. Schütz May 2016).

37

Fig. 1.3. The obelisk standing on the Piazza di San Pietro in

the Vatican, also known as the `Vatican obelisk´. This obelisk was made for the

Forum Iulium at Alexandria and dedicated by Gaius Cornelius Gallus at the order

of Octavian/ Augustus, who had also commissioned the Forum Iulium. Caligula

brought this obelisk to Rome and erected it in the circus of his horti at

the ager Vaticanus. By doing so, he

copied Augustus’ concept of placing an obelisk on the spina in the Circus Maximus; cf. n. 210, chapters

Domitian's Obelisk, the Obeliscus Pamphilius, Appendix 1, Appendix 10, VIII.

EPILOGUE (photo: F. X. Schütz).

38

Fig. 1.4. The reconstructed Ara

Pacis Augustae in Rome; cf. n. 24, 25, 45, 48, 49, 50, 57, 58, 242, 279,

Appendix 2; Appendix 6, chapter VIII. EPILOGUE, Figs. 3.7; 3.8, label: Museo dell'ARA PACIS (photo: F. X. Schütz

May 2016). Note that this is the west-side of the precinct that surrounds the

altar proper. In the current installation, this side is now oriented to the

south.

39

|

|

|

Left:

Fig.

1.5. The obelisk (one of a

pair) standing behind the Church of S. Maria Maggiore in Rome, also known as

the `Esquiline obelisk´. Augustus commissioned this obelisk for his Mausoleum (photo: F.X. Schütz May 2016).

Right:

Fig.

1.6. The obelisk (one of a

pair) standing in front of the Palazzo del Qurinale in Rome, also known as the

`Quirinal obelisk´. Augustus commissioned this obelisk for his Mausoleum. Cf. Fig. 3.7, label: Fontana di Monte Cavallo/ `Quirinal obelisk´

(photo: F.X. Schütz May 2016).

See

for both obelisks: n. 128 and chapters Domitian's Obelisk, the Obeliscus

Pamphilius, Appendix 1; Appendix 8; Appendix 10; The Mausoleum Augusti and its two obelisks, VIII. EPILOGUE, Fig. 10.1.

40

|

|

|

Left: Fig.

1.7. `Cleopatra's Needle´

(one of a pair of obelisks), London, Victoria Embankment. Augustus brought this

obelisk from Heliopolis to Alexandria and erected it in front of the Temple of

the divinized Caesar; cf. Appendix 1, Appendix 4 (photo: F.X. Schütz

21-II-2016).

Right: Fig.

1.8. `Cleopatra's Needle´

(one of a pair of obelisks), New York City, Central Park. Augustus brought this

obelisk from Heliopolis to Alexandria and erected it in front of the Temple of

the divinized Caesar; cf. Appendix 1, Appendix 4. After: L. Habachi 2000, Fig.

95 on p. 99.

See

for both obelisks: chapters Domitian's Obelisk, the Obeliscus Pamphilius, VIII.

EPILOGUE.

41

Fig. 1.9.

The Mausoleum Augusti in Rome.

Augustus began, as some scholars suggest, in 31 BC, or rather in 29, after his

return from Alexandria, to build this dynastic tomb for his family; cf. n. 128;

Appendix 10 (photo: F. X. Schütz 1-X-2016).

42

The raison d' être of Frischer's computer

simulation is of course in the first place - as in the cases of all of us who

are concerned with reconstructions of ancient Rome - to create serious

visualizations of his own interpretation(s) of the meaning(s) of the ensemble

of buildings in question.

As Frischer and

Fillwalk were earlier able to demonstrate, September 23rd `does not

work´ in the way as Edmund Buchner had suggested[13], which, as their

simulation proved, was not the case.

Buchner

wrote: "Die Äquinoktienlinie ist eine Gerade, genau in der Ost-West-Achse,

die anderen Tierkreiszeichenlinien sind Hyperbeln [cf. his Fig. 6]"; "Welch

eine Symbolik! Am Geburtstag des Kaisers ... wandert der Schatten von Morgen

bis Abend etwa 150 m weit die schnurgerade Äquinoktienlinie entlang genau zur

Mitte der Ara Pacis"[14]; es führt so eine direkte Linie von

der Geburt dieses Mannes zu Pax, und es wird sichtbar demonstriert, daß er natus ad pacem ist[15]. Der Schatten kommt von einer Kugel,

und die Kugel (zwischen den Läufen eines Capricorn etwa) ist zugleich wie

Himmels- so auch Weltkugel, Symbol der Herrschaft über die Welt, die jetzt

befriedet ist. Die Kugel aber wird getragen von dem Obelisken, dem Denkmal des

Sieges über Ägypten (und Marcus Antonius) als Voraussetzung des Friedens. An

der Wendelinie des Capricorn, der Empfängnislinie des Kaisers, fängt die Sonne

wieder an zu steigen. Mit Augustus beginnt also - an Solarium und Ara Pacis ist

es sichtbar - ein neuer Tag und ein neues Jahr: eine neue Ära, und zwar eine

Ära des Friedens mit all seinen Segnungen, mit Fülle, Üppigkeit,

Glückseligkeit. Diese Anlage ist

sozusagen das Horoskop des neuen Herrschers, riesig in den Ausmaßen und auf

kosmische Zusammenhänge deutend" (my italics).

Frischer has

now revised his opinion[16], cf. also infra. Interestingly, this date, 23rd

September, was chosen by Augustus, it

was not his real birthday[17]. I interpret this choice

as a means to say: `I am the son of Julius

43

Caesar and a direct descendent of

the goddess Venus[18], which was already

outlined in the stars when I was born´.

One of Frischer

and Fillwalk's earlier suggestions which Frischer has now abandoned, namely

that 9th October, the dies

natalis of Augustus' Temple of Apollo Palatinus (instead of 23rd September)

could have been the intended date[19], meaning: Octavian/

Augustus is the son of Apollo, sounded at first very intriguing to me because

Octavian/ Augustus[20] had been also Pharaoh of

Egypt since 30 BC[21]. This was actually the

reason

44

why I took an interest in the subject discussed here. Because, following

this hypothesis, this could mean: I, Augustus, am the son of the Egyptian

sun-god Re. Like the Egyptologist Friederike Herklotz[22], I have myself recently

studied this aspect of the construction of the rôle of the Roman emperor[23]. For the controversy

concerning the question, whether or not Augustus was Pharaoh of Egypt, cf.

Appendix 12 and the Contribution by Nicola Barbagli, infra, pp. 566ff., 651ff.

As we shall see

in chapter II, both Augustus and the Ara Pacis had anyway very close relations

to Apollo - which is why there was no real `need´ that the obelisk's shadow

would hit the Ara Pacis on October 9th. There appear, as a matter of

fact, in prominent positions some swans within the floral scroll reliefs of the

Ara Pacis; those birds are clearly related to Apollo[24]. The claim: I, Augustus,

am the son of the sun-god (Apollo and of Re; cf. infra), in my opinion is

in fact `visualized´ by the Ara Pacis - as I only realized by writing this

email to Bernard Frischer after his talk - and no other Augustan building would

qualify better.

To be precise:

the iconography of the Ara Pacis shows the blessings of Augustus' reign[25], of course, but those

achievements are exactly the same that already the king of Egypt in pharaonic

times had been expected to provide his people with. The Egyptian pharaoh, and

thus now Octavian/ Augustus, was believed by the Egyptians to be the son of the

sun-god Re[26],

who was (among other things) the force that enabled him to provide his subjects

with these blessings. Therefore, the pharaoh was the bringer of prosperity[27] because his

45

most important duty, to be achieved by actions and rituals he had to perform on a

daily basis and/ or on special occasions, was to establish Ma'at[28].

The

Egyptologist Alessia Amenta lists some of the relevant obligations of the king,

for example that of being "vincitore sui nemici dell'Egitto e sui demoni

dell'Aldilà, conquistatore di terre lontane e anche del cielo, garante di vita

eterna ... Costruendo il tempio e mantenendolo in vita attraverso lo

svolgimento del culto, sconfiggendo i nemici e amministrando con giustizia il

paese, dunque, il faraone realizza Maat"[29].

Another, so far

not mentioned obligation of the king concerned likewise the gods: "In

traditional Egyptian theology the gods must be renewed each day to retain their

eternal youth", writes Frederick E. Brenk[30]. Another task of the

pharaoh was to guarantee the yearly Nile Flood[31]. The pharaoh's

establishment of Ma'at resulted in justice and peace on earth and

in the sphere of the gods (!)[32], and that in turn

resulted in universal prosperity for his people[33].

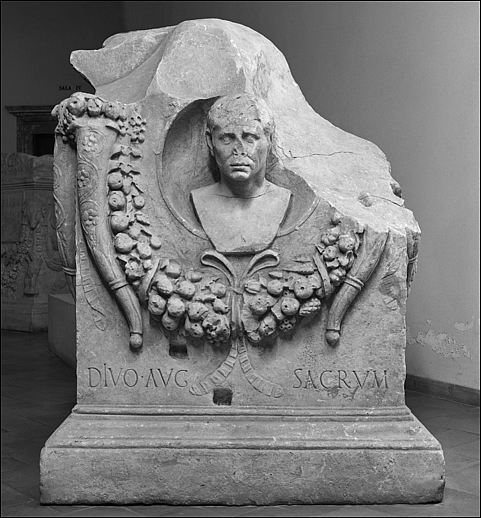

The altar

dedicated to Divus Augustus who was wearing a radiate crown

That exactly

these positive results of the monarch's reign - without indicating the cause

(but see below) - was also represented in Roman art, shows the marble altar at

Praeneste/ Palestrina which was dedicated posthumously to the deified Augustus,

who was wearing a (now lost) radiate crown (Fig. 2)[34]. The cornucopiae of this altar symbolize according to Paul Zanker the

`universal prosperity´, brought about by Augustus. In discussing this altar,

Zanker also mentions the Ara Pacis as `symbol of peace and universal

well-being´[35]

- because both monuments have basically the same meaning[36]. And nobody doubts that

the Ara Pacis is the building par excellence that celebrates the

`Augustan peace and prosperity´. The Ara Pacis was also a victory monument that

`symbolized the settlement of the western provinces´, as Robert Hannah reminds

us, and Eugenio La Rocca observes that `the supplicationes

performed on the day of its dedication, January 30th, 9 BC, were for

Augustus' imperium, as a guarantor of

the empire´[37]

(!).

46

Fig. 2. Marble altar dedicated to Divus Augustus. Palestrina,

Museo Barberiano (inv. no. not indicated; Iacopi 1973, no. 77: `found in recent

excavations at Praeneste; macellum´);

cf. ns. 34, 36, 94 and the Contribution by W. Trillmich in this Volume. After

Häuber 2014, p. 43 Fig. 17d.

47

Another issue

is also of importance. Somebody said after Frischer's talk: `I doubt that the

shadow was visible at all to someone who stood at the Ara Pacis on the day in

question´. From a technical point of view shadows constructed by applying

computer simulations are very reliable. Whether or not in reality shadows are in fact visible

to someone, or are at all noticed by this person, is, of course, a very

different, and at the same time very complex matter. In connection with the

observation that the Ara Pacis has something to do with Apollo, the authors

contributing to Frischer's article mention apart from the temple of Apollo

Sosianus[38]

also the temple of Apollo on the Palatine[39]. I myself[40] follow the ideas of T.P.

Wiseman[41] and Amanda Claridge

concerning the domus of Augustus on

the Palatine and the Temple of Apollo Palatinus (cf. here Fig. 3.5, labels: PALATINE; DOMUS: "AUGUSTUS"; DOMUS

AUGUSTANA; TEMPLUM: APOLLO). According to Claridge[42], the temple of Apollo

Palatinus faced north-east, not south-west, as is usually taken for granted.

This finding has important consequences for the so far published theories

concerning the iconographic `impact´ of this temple on its immediate, as well

as on its farther distant surroundings.

48

[1] Wiseman 2015, 95; cf. Wiseman 2016b, 108. `Liberation of the republic

from the domination of a faction´, refers to Augustus' Res gestae. For that and for the actual historical events referred

to by Augustus, cf. Wiseman forthcoming1, 15th page: "30.

Augustus Res gestae 1.1-4", and passim. For Octavian/ Augustus, 63 BC-14

AD (reigned 30 BC-14 AD), "the first emperor at Rome", cf. Nicholas

Purcell 1996, 216-218. On p. 218, he mentions that Augustus used "ethics

as a constitutional strategy"; cf. infra,

pp. 375-376 with n. 202 and pp. 549-550. For Caesar, cf. infra, n. 76. For a different image of Augustus than that painted

by Wiseman, because arguing from the point of view of the optimates, cf. Gotter 2012. For populares

and optimates, cf. infra, the text belonging to n. 180; and

Wiseman 2016b, passim. Williams 2001,

190, discusses the fact that "The nature of Octavian's interpretation of

what his posthumous adoption meant was ... rather irregular" (cf. infra, n. 203 and Appendix 11, p. 563ff.);

p. 197: "On some of the inscribed religious calendars that survive from

the first century AD, the Kalends (1st) of August, the date on which Octavian

captured Alexandria in 30 BC is noted as the day `on which Imperator Caesar

[Augustus] freed the Commonwealth (rem

publicam) from a most grievous danger´"; cf. id. 2000, 138, 142.

According to other scholars, the date on which Augustus had captured

Alexandria, was later defined as having been 8. Meroe (= August 2nd),

cf. Joseph Mélèze Modrzejewski 2001, 466, quoted verbatim in Appendix 12, infra,

p. 566ff. For Augustus, cf. also Syme 1939; id. 1957; La Rocca et al. 2013; Galinsky 1996; id. 2012;

id. 2013; Eck 2014; Zimmermann, von den Hoff, Stroh 2014; and Sheldon

forthcoming.

[2] "New Research on Edmund Buchner's Solarium Augusti", talk

delivered at the Kommission für Alte Geschichte und Epigraphik, München on 3rd

July 2015.

[3] cf. Frischer et al. 2017; Häuber 2017. Bernard Frischer was so kind as to revise the English of the latter

text, and because some passages of it appear also in this study, I have changed

some of the relevant parts of this text according to his corrections - with his

kind consent.

[4] Chrystina Häuber, email of 5th July 2015.

[5] cf. Häuber, Schütz 1997; id. 1998; id. 1999; id. 2001a; id. 2001b; id.

2004; id. 2005; id. 2006; id. 2010; Häuber et

al. 2001; cf. J. Bodel 2001; and E. La Rocca 2001; F.X. Schütz 2008; id.

2013; id. 2014; id. 2015; and his Contribution in this volume; Häuber, Schütz,

Winder 2014; Häuber 2014, Maps 3-18; ead. 2015. For the applied methodology, cf. also

Häuber, Schütz, Spiegel 1999; Häuber, Nußbaum, Schütz, Spiegel 2004.

[6] cf. Schneider 2004,

esp. pp. 161-167.

[7] so Frischer 2017, 23, quoting: "P. Albèri Auber 2014: 73" and

"M. Schütz 2014[a]:44" respectively,

cf. p. 33 with n. 33, p. 36. The height suggested by Albèri Auber 2014 for the

Montecitorio Obelisk (here Fig. 1.1)

was challenged by M. Schütz 2014b, esp. p. 99, wo contradicts this assumption;

cf. Haselberger 2014b; id. 2014d, 192 with n. 77. Albèri Auber 2014-2015, pp.

453, 454, 458, 461, 465, 470, discusses the different heights of the

Montecitorio Obelisk suggested by himself and M. Schütz and maintains his

suggestion [cf. Albèri Auber 2014, 76; cf. pp. 72-73] that the obelisk was 100

Roman feet high [so already Buchner 1982, 8-19, 47, 48, Fig. 17; id. 1996a, 35:

"also ca. 29.5 m"; cf. p. 36; and here Appendix 2, p. 388ff.]. I

thank Paolo Liverani for providing me with a copy of this article.

Albèri

Auber 2014-2015 still reconstructs the Montecitorio Obelisk (see his Figs. 1

and 3 on pp. 457, 459) with a "c.[irca]

1 m-long `distance rod´ supposedly between the tip of the obelisk and its

sphere", as Haselberger 2014d, 193; cf. p. 192, calls this detail of this

obelisk's finial - without discussing the following convincing remark by

Haselberger 2014d, 193 with n. 83: "this is not remotely similar to the

Antonine depiction of the Campus Martius obelisk, which shows the sphere's

attachment in detail", quoting for that relief in n. 83: "Alberi

Auber 2011-12, 515 fig. 26".

For

the relief in question, the "Pedestal of the column of Antoninus Pius,

apotheosis, 161 [AD]. Rome, Vatican Museums, Cortile delle Corazze", cf.

Kleiner 1992, 286, Fig. 253; Buchner 1982, Taf. 111,1 and front cover;

Schneider 1997, 111, Pl. 10.2; Claridge 1998, 193, Fig. 87; ead. 2010, 216,

Fig. 87; Schneider 2004, 166-167, Fig. 16; id. 2005, 422-423 with n. 31, p. 424

with n. 35, Fig. 6; Haselberger 2014c, 18 with n. 5, Fig. 3 [2011].

Paolo

Liverani, who was so kind as to read this section of my manuscript, wrote me

the following comment which I am allowed to publish here: "Haselberger's

remarks [id. 2014d, 193 with n. 83] are far from convincing! Non si è accorto

che la sfera dell'obelisco nel rilievo di Antonino Pio è di restauro! Alberi invece

lo sa bene (glielo ho detto io) e credo che lo dice in qualche punto del suo

primo articolo. La gente guarda le foto ma non i monumenti!".

[8] cf. infra, n. 216 and

Appendix 1, infra, p. 382ff.

[9] I was therefore pleased to learn that not only John Pollini has created

such a wooden model of the Montecitorio Obelisk (scale 1: 100), in order to

support his relevant research (cf. Pollini with Cipolla 2014, 59 with Figs.

3-4), but also Bernard Frischer; cf. Frischer and Fillwalk 2014, 86, caption of

Fig. 4: "small-scale model 30 cm in height (B. Frischer)", and Lothar

Haselberger; cf. id. 2014d, 197, with caption of Fig. 10: "Practical

demonstration of the precise, `mechanical´ linkage between a light source and

its shadow cast by a [small] gnomon-obelisk ...".

Labib

Habachi 2000, 109, wrote about the obelisk standing in front of the Church of

SS. Trinità

dei Monti [here Fig. 4; cf. infra, n. 63]: 1789 wurde er "unter Papst Pius VI. an seinen

heutigen Standort versetzt. Zur Überprüfung der Wirkung des Steinpfeilers im

Stadtbild ließ der Papst sogar vorab ein Holzmodell des Monolithen im Maßstab

1:1 anfertigen und auf der Trinità dei Monti aufstellen. Das Ergebnis scheint

zur Zufriedenheit aller Beteiligten

ausgefallen zu sein, denn im Anschluß daran begann man mit den notwendigen

Baumaßnahmen" (my italics).

We

learn from Gino Cipriani 1982, 50, why it had been necessary to obtain this

`consensus´: "L'idea di elevarlo [the `obelisk Horti Sallustiani´] davanti alla facciata di Trinità dei Monti al

Pincio cominciò ad essere studiata sino dal 1787; ma l'attuazione avvenne solo

nell' aprile del 1789, tre mesi prima della presa della Bastiglia [i.e., `la

Bastille´!], per opera dell'architetto Giovanni Antinori. E' curioso rilevare

come i frati Minori cui era affidata la chiesa furono ostili all'iniziativa

facendo il possibile perchè quel collocamento, che tanto completa la bella

scenografia dello Specchi e De Sanctis, non avenisse".

See

his fig. 29 on p. 51, the caption of which reads: "La lunga scala che

dalla strada di San Sebastianello conduce sul ripiano di Trinità dei Monti

[with the obelisk already in place]. Così la vide e disegnò [J.A. Dominique]

Ingres [August 29th, 1780-January 14th, 1867] quando era

<<prix de Rome>> all'Accademia francese di villa Medici"; cf.

his Figs. 30; 31.

For

the extremely deep foundation of this obelisk, see also the Contribution by

Vincent Jolivet in this volume, infra,

p. 673ff.

Also

Edmund Buchner 1982, 12 with n. 45 [= id. 1976, 333 with n. 45], mentions the

importance of the use of dummies in the process of constructing a sundial:

"Bei allen Sonnenuhren müssen natürlich Breitengrad (= Sonnenstand an den

Äquinoktien) und Ekliptik möglichst genau beachtet werden ... Der Breitengrad läßt

sich zweimal im Jahr empirische exakt festlegen, wobei sich auch das Problem

Randschatten, auf das noch einzugehen sein wird, ausschalten läßt [with n.

45]"; cf. n. 45: "Den genauesten Wert erhielt man, wenn man an den

Äquinoktien - wenn die Schattenlinie auf einer horizontalen Fläche genau eine

Gerade bildet (Abb. 5) - eine Kugel (oder anderen Gegenstand) mit dem

vorgesehenen Durchmesser in 100 Fuß Höhe anbrachte".

[10] M. Schütz 2014a [2011]; and Appendix 2, infra, p. 388ff.; cf. Hannah 2014, esp. p. 111 with n. 13.

[11] cf. Grewe 1998, 97-98; Häuber 2014, 295. For Claudius, cf. infra, n. 268. For Agrippina minor, cf. infra, n. 278.

[12] cf. M. Schütz 2014a, 45-46 [2011] on the "Purpose of the meridian

instrument [under scrutiny here]"; p. 45 with n. 8: "From antiquity

to modern times, a meridian provided the basic parameters for mathematical

astronomy and astronomical geography ... Astronomers such as Menelaos and his

circle could therefore use a meridian for educational purposes as well as for

scholarly research. The most elementary

problem consisted in determining the length of the year, because completely

depending on this was the calculation of the positions of sun, moon, and

planets for each day according to the zodiacal sign and degree. Even in the

3rd. c.[entury] A.D. Censorinus states (DN

19-20):

The year is

the amount of time within which the sun wanders through the twelve signs of the

zodiac, returning to its original

position. But

up to now, astronomers could not exactly determine how many days are contained

in this span of time.

The

length of the year was determined in antiquity by observing the solstices and -

especially important - the equinoxes. Serving this purpose was the gnomon.

Ideally one had to determine the equinoxes' point of time with the accuracy of

an hour. In this context, the "shadow-casting" border walls along the

meridian line deserve attention [with n. 10; referring to Augustus' Meridian

device; cf. infra, n. 75; and Fig. 3.6, labels: Wall 1; Excavated

Meridian line; Wall 2]. Assuming that these border walls ran, indeed, exactly

parallel to the meridian line, then the E[astern] border wall cast its shadow

onto the meridian line in the morning, the W[estern] one in the afternoon, while there was no shadow at precise

noontime - for about 3 minutes. Thus, true noon could be ascertained with high

accuracy ... Averaging the time

difference between the dates of several years then leads to the desired amount

of a year's length. A meridian was the crucial tool for this" (my

italics); p. 46: "In all, determining the length of a year created a major

challenge throughout antiquity and beyond. Addressing that challenge emerges as

the key rôle of a meridian instrument. In

short, the function of a meridian instrument alone complies perfectly well with

the evidence and context available for the meridian in the Campus Martius. It

is neither necessary nor justified to postulate a full sundial" (my

emphasis). In n. 10 on p. 45, M. Schütz 2014a [20111] writes: "For the

evidence of these lost but well-attested border walls, see Haselberger 2011,

54-55 (= above, [i.e. Haselberger 2014c] 22-23), with fig. 7; Buchner 1982,

69".

The

latter observation, marked in bold, sounds in my opinion convincing; so also

Heslin 2014, 39, 40 [2011]; Pollini with Cipolla 2014, 53; and Frischer and

Fillwalk 2014, 78. But the matter is by no means settled; cf. Hannah 2014,

115-116; and Haselberger 2014c, 17 with n. 4, pp. 36-37 [2011]; id. 2014d,

168-170 with n. 9, pp. 171-173 with ns. 14, 15, pp. 200-201 with n. 100; cf. infra, ns. 72, 175, 176, 190-194; and

Appendix 6, p. 429ff.

[13] see Buchner 1982, 37 (= id. 1976, 347) with n. 81; cf. Appendix 2, infra, p. 388ff.

[14] Buchner 1982, 23, 37 with ns. 82-84 [= id. 1976, 335, 347 with ns.

82-84]. As we shall see in Appendix 2, Buchner's assertion is impossible.

Although based on a minor misunderstanding of Buchner's relevant text (but cf.

Appendix 2, infra, p. 388ff.),

Frischer and Fillwalk 2014 were nevertheless right. For the demonstration of

this, cf. Frischer and Fillwalk 2014, Fig. 1 on p. 82. Its caption reads:

""Campus Martius, digital simulation of Ara Pacis and shadow of

gnomon-obelisk at sunset on September 23, A.D. 1. The shadow of the obelisk

does not hit the middle of the Ara's W[est] façade, as required by the

"strong" reading of Buchner's thesis; it only grazes the lower right

(S)[south] side of the façade before continuing to the right beyond the altar

(Frischer-Fillwalk simulation)""; for the `"strong" reading

of Buchner's thesis´, cf. Frischer and Fillwalk 2014, pp. 80-81. Frischer and

Fillwalk 2014, 79 with ns. 11-13, offer an explanation for this: "Buchner

placed the obelisk c.[irca] 2 m too

far east (i.e., in the direction of the Ara Pacis): he measured the distance

from the obelisk to the W[west] façade of the Ara Pacis as c.[irca] 87 m, but we find that it is 89 m". Pollini with

Cipolla 2014, 57 with n. 20, report this differently: "this is based on

their [Frischer and Fillwalk 2014's] measurement of the distance from the base

of the obelisk to the Ara Pacis, which differs from that of Buchner by c.[irca] 4-5 m".

For

the Ara Pacis Augustae, cf. M. Torelli: "Pax Augusta, Ara",

in: LTUR IV (1999) 70-74, Figs.

17-22; V (1999) 285-286 (with further bibliography).

[15] cf. La Rocca 1983, 57, quoted verbatim,

Appendix 2, infra, p. 388ff. Cf.

Pollini 2017, 56: "Augustus was

born to bring peace to the world (natus

ad pacem)". In the relevant footnote 98, he writes: "For this

neologism, see Buchner 1982:37". He continues: "The new simulations

published here are based on Frischer's forthcoming correction of Buchner's

positioning of the meridian fragment and obelisk on the map of contemporary

Rome, and they update the position of the shadow in relation to the Ara Pacis

on Augustus' birthday. They show that at that time the shadow of the obelisk

with its finial fell on the western staircase of the altar (Fig. 18)"; cf.

infra, n. 74 and Appendix 2, infra, p. 388ff. Cf. Frischer 2017,

19ff. La Rocca 2014, p. 158 writes: "regardless of whether or not the

obelisk was included within an articulated calendrical system - this

relationship was carefully rephrased as a new metaphor: following the gods'

will, the princeps was born to bring

peace and prosperity to the people". Cf. Appendix 6, infra p. 429ff.

[16] Frischer 2017, 84, has come to almost the same conclusion as I myself,

although he has based it on different evidence than I will do in the following

(cf. infra, n. 199). He writes:

""If a new slogan is sought, one might emend Buchner's text to read:

"Augustus was natus ad pacem

because of his devotion to Sol-Apollo". That is, Augustus' ability to

bring Rome victory in war and prosperity in time of peace was made possible by

the divine origin and sanction of his rule as well as by his own pietas"".

[17] cf. Häuber 2014, 729 note 11: "Interestingly, the horoscope of

Octavian/ Augustus was a clever forgery (and we may wonder, which birthday he

had told Theogenes). BARBONE 2013, p. 89, writes: "il principe [Octavian/

Augustus] voleva che il suo natale

cadesse il 23 [September]", explaining also the reasons for that choice;

cf. p. 91: "Capricorno era il segno del suo concepimento": by

choosing September 23rd as his birthday, Octavian/ Augustus stressed

his close relation to Venus, the planet, reigning the zodiacal sign libra, and thus, as the adopted son of

Julius Caesar, to be the direct descendent of Venus, the goddess"".

For further observations concerning Augustus' birthday, cf. M. Schütz 1990,

446-448. For verbatim quotes, cf.

Appendix 2, infra, p. 388ff.; M.

Schütz 2014a, 49 [2011]; Hannah 2014, 109-110 [2011]; La Rocca 2014, 122 n. 5,

pp. 128, 154, 155 with n. 158, p. 156 with n. 161; Haselberger 2014d, 190 with

n. 69, pp. 191, 199: here he calls it: "Augustus' official birthday" (my italics).

As

I have only found out recently, Capricorn was not the sign of Augustus' conception (nor was it winter solstice),

as asserted by Buchner. The emperor had, instead, been born under that sign. Cf. infra,

ns. 216, 297.

For

Augustus' birthday, cf. now also Angela Pabst 2014, 68-70. I thank Stefan

Pfeiffer for the reference.

[18] so also Pollini with Cipolla 2014, 56; and Pollini 2017, 61-62 with n.

125.

For

a different hypothesis, La Rocca 2014, 124, 127, 128, 131, 134, 151-152.

Analysing the site that was chosen for Agrippa's Pantheon, the former palus

Caprae (cf. his Figs. 2; 3), and because of the following, La Rocca

believes that Augustus' propagated birthday, September 23, 63 BC, aimed at his

own equation with Romulus; p. 128 with n. 25: "The spot of sunlight inside

the Hadrianic (but perhaps also the Augustan) Pantheon from the oculus falls above the entrance locally

at noon on the autumn equinox, the birthday of Augustus. After that, the beam

moves down, illuminating the entrance, which is `crossed´ at noon on April 21,

the birthday of Rome"; p. 131: "This [the palus Caprae] is where the ascensio

ad astra of the first king of Rome took place"; p. 135: "the

Pantheon whose exceptional architectural structure was perhaps meant to

emphasize the same spot where, according to one version of the legend, Romulus

ascended to the sky"; p. 124: "Augustus would have presented himself

ideally as a second Romulus, a re-founder of the city under the sign of peace

and the birth of a new golden age"; cf. pp.151-152, quoted verbatim infra, text related to n. 181, and in n. 287. La Rocca 2015a, in

his chapter "Il Pantheon come luogo di commemoratio e di culto

imperiale", writes on p. 55: "Filippo Coarelli [with n. 147] ha

acutamente intuito che la scelta del sito dove costruire il Pantheon sia correlato con la leggenda

della scomparsa di Romolo (Fig. 1)"; cf. n. 147: "COARELLI 1983, p.

41 ss. spec.[ialmente] p. 45. Vd.[edi] inoltre: RODDAZ 1984, p. 275 s.; THOMAS

1997, p. 163 s.; THOMAS 2004, p. 30".

[19] cf. Frischer and Fillwalk 2014, 88-89 with Fig. 6; Frischer 2017, 21.

[20] cf. Hölbl 2004b; Häuber 2014, 735 with n. 68: "Hölbl [2004b]

traces the development from the Egyptian pharaoh to the Roman pharaoh (the

Roman emperor as pharaoh of Egypt) from Octavian/ Augustus to Diocletian, who

interpreted this rôle very differently ...". Cf. Hölbl 1996; id. 2005b.

Some relevant passages are quoted in Appendix 12, infra, p. 566ff.

[21] cf. Herklotz 2007, 220

with n. 589: "Und schließlich war er [Augustus] für die Ägypter der

Pharao, denn dieser war der inkarnierte Sonnengott Re-Apollon"; p. 209:

"Durch die Einbindung des Augustus in die altägyptische Königsideologie

war es den Priestern möglich, sich mit der römischen Herrschaft zu arrangieren.

Für Augustus dagegen stellte die Unterstützung und Förderung der ägyptischen

Religion ein wichtiges Mittel bei der Legitimierung seiner Macht und dem Erhalt

des inneren Friedens in einer der reichsten Provinzen des Römischen Reiches

dar". Cf. Herklotz 2012. I thank John Pollini for the

reference.

For

a detailed discussion concerning the controvery, whether or not Octavian/

Augustus was Pharaoh of Egypt, cf. Appendix 12 and the Contribution by Nicola

Barbagli, infra, p. 651ff. Cf. La

Rocca 2014, 145-46 with ns. 102, 103; Haselberger 2014d, 198.

M.J.

Versluys 2010, 19 with n. 39 remarks on Aegyptiaca: "It evokes imperial

connotations and monumentality: obelisks are (and remain) symbols of the sun

after having been transported to Rome but they develop into a most spectacular

symbol of imperial power (fig. 1)". I thank Miguel John Versluys for

providing me with a copy of this publication.

Stefan

Pfeiffer, who was so kind as to read my manuscript, wrote me on 27th August

2016, the following comment concerning the two equal Latin inscriptions on the

Montecitorio Obelisk: `... redigere

kann auch "einziehen, verwandeln, in etwas aufnehmen", heißen. Ägypten war selbständiges

Königreich und der Ptolemäerkönig amicus

et socius der Römer ...[Ägypten] wurde mit der Eroberung römische Provinz,

wurde also "in die Verfügungsgewalt des römischen Volkes versetzt"´.

See also Joseph Mélèze Modrzejewski 2001, 459. Cf. S. Pfeiffer 2015, 225-228:

"48. Das solarium Augusti in Rom

(zwischen 26. Juni 10 und 25. Juni 9 v. Chr.), with annotated

bibliography on p. 228. On pp. 225-226, he translates the inscription as

follows: "Imperator Caesar, Sohn Gottes, Augustus, pontifex maximus, zum 12. Mal Imperator, zum 11. Mal Konsul, zum 14. Mal

Inhaber der tribunizischen Gewalt, hat, nachdem/weil Ägypten in die

Verfügungsgewalt des römischen Volkes versetzt worden war, (den Obelisken) dem

Sol als Geschenk gegeben". On p. 228, he writes: "E. Winter ... [II

2013] 522-527 (aktuelle Darstellung des Forschungsstands)". I thank Stefan Pfeiffer for providing me with copy of this publication.

Pollini

2017, 54, translates and comments the inscription differently: ""The

pertinent part of the Latin inscription on the base of the [Montecitorio]

obelisk [here Fig. 1.1] makes clear

that it was to be understood as a Roman victory monument dedicated to Sol: Augustus ... Aegypto [note that in both inscriptions the term is written:

AEGVPTO; autopsy: 29-V-2016. So also Buchner 1996, 36; and Pfeiffer 2015, 225] in potestatem populi Romani redacta Soli

donum dedit ("with Egypt restored to the power of the Roman people,

Augustus dedicated [this] to Sol") [CIL

6.702 = ILS 91]. With Egypt again

under Roman sway, Augustus had now become the direct successor of the Ptolemies

and officially the upholder of ancient Egyptian religious

traditions"". In the pertaining footnote 92 he writes: "Prior to

Octavian's conquest of Egypt in 30 BC, the country under the Ptolemies had become

so weakened that it became de facto a

protectorate of Rome, hence Caesar's intervention on the matter of who would

rule Egypt. This is why the specific verb redacta

(`having been restored/brought back´) is used with Aegyptus in the dedicatory inscription"". For the

political situation to which Pollini here refers, cf. Maedows 2000; id. 2001.

For

the precise date of this inscription, cf. also Buchner 1982, 10, Taf. 109,1 (=

id. 1976, 322, Taf. 109,1); and La Rocca 2014, 121 with ns. 2, 3:

"According to the socle inscription ... Augustus dedicated the obelisk at

the time of his fourteenth tribunicia

potestas - that is, between the second half of 10 B.C. and the first half

of 9 B.C.; this may have coincided with the dedication of the Ara Pacis by the

Senate on January 30, 9 B.C."; in his n. 3, La Rocca, op.cit., writes: "Another possibility ... is that the obelisk

had been dedicated on August 1, 10 B.C., on the occasion of the 20-year

celebration for the conquest of Alexandria"; cf. pp. 133-134 with n. 40; p.

141: "The two obelisks [referring also to the obelisk, here Fig. 1.2] were dedicated when Augustus

was tribune for the 14th time (from June 26, 10 B.C. to 25 June of the

following year). As an hypothesis, one could suggest narrowing down the dating

to August 1, 10 B.C., on the twentieth anniversary of the victory over

Alexandria, or to January 30, 9 B.C., to coincide with the dedication of the

Ara Pacis, or to another day closer to the calendrical reform which took place

in 9 B.C."; cf. pp. 143-144, 149-151 (further for the Montecitorio Obelisk

and its inscription, and for the reason, why Augustus dedicated this Obelisk to

Sol); p. 143: the inscription reads: "Imp(erator) Caesar divi f(ilius) /

Augustus / pontifex maximus / imp(erator) XII co(n)s(ul) XI trib(unicia)

pot(estate) XIV / Aegupto in potestatem / populi Romani redacta / Soli donum

dedit".

Further

for the inscription of the Montecitorio Obelisk, cf. Schneider 2004, 164, 167.

Cf. Michele Salzman 2017, 74: "Just as Augustus sought to associate his victory

over the Egyptian queen Cleopatra with the divine power of his defeated enemy,

so too, Aurelian could associate his victory over the defeated Eastern queen

Zenobia with the divine power of the Palmyrene Sol"; cf. op.cit., p. 75: "If I am correct, the

celebration of the dedication of Aurelian's [Sol] temple on December 25th

in the Campus Agrippae area follows Augustan precedent by linking Aurelian's

victory and Sol worship with Augustus's victory and the Egyptian Sol

cult".

Also

Augustus himself (who was born under the sign Capricorn), as well as his

Meridian device, were closely related to the winter solstice, cf. infra, n. 216; and chapter VII. SUMMARY:

What is left of E. Buchner's hypotheses

concerning his `Horologium Augusti´? Cf. infra, p. 582ff. For a reconstruction of Aurelian's Temple of Sol,

cf. Torelli 1992; followed by Häuber 2014, 404-406. Cf. Liverani 2004; id.

2006-2007, 302-303, with a discussion of all so far suggested reconstructions;

La Rocca 2014, 140 with n. 71.

[22] cf. Herklotz 2007, 209-220, and passim;

Strocka 1980.

[23] Häuber 2014, 695-744, chapters B 25.-B 28., esp. pp. 733-736, on the

iconography of the bust of Commodus as Hercules Romanus, here Fig. 6; cf. Lembke, Fluck; Vittmann

2004, 5-12. Cf. supra, n. 20.

[24] cf. La Rocca 1983, 18: "Il Fregio a girali di acanto ... Su alcuni

rami, in alto, in posizione araldica, si dispongono cigni ad ali

spiegate", see the photos on pp. 19, 22; p. 20: "Non grosse

difficoltà offre anche l'interpretazione del tema. I girali di acanto intorno a

cui si annodano altre piante, simboleggiano l'avvento

dell' età d'oro, di un periodo di pace e prosperità sotto la guida

dell'imperatore [Augustus], e sotto

lo sguardo benevolo degli suoi protettori, in principal modo Apollo il cui

simbolo - il cigno - domina nel fregio" (my italics); cf. p. 57.

Cf.

Pollini 2012, 271-308, esp. Figs. VI.5, VI.7. My thanks are due to John Pollini

who presented me a copy of this book. Cf. Pollini 2017; and infra, ns. 32, 94; Frischer and Fillwalk

2014, 89; cf. M. Swetnam-Burland 2017, 45 with n. 59.

[25] cf. previous note.

[26] Herklotz 2007, 219: "Der Pharao ist der Sohn des Sonnengottes

Re"; cf. p. 220 with n. 589, pp. 227-228, quoted verbatim infra, n. 89; cf. Swetnam-Burland 2017, 41: "The

Montecitorio obelisk [here Fig. 1.1]

... was commissioned by the second and third kings of the 26th

Dynasty, Necho II and his son Psametik II (r.[eigned] 610-595 and r.[eigned]

594-589 BC) ... It was most likely one of a pair, as were most Egyptian

obelisks, erected in the city of Heliopolis ... The Egyptian inscription on the

... [Montecitorio Obelisk] - though only partially preserved ... states that this obelisk honored the

sun-god Re-Harakhti, an incarnation of the sun-god that celebrated his rise at

dawn. The text of the Montecitorio Obelisk affirms his role in granting the

king life, happiness, and power ...". Frischer 2017, 76, commenting on

this, writes: "Hence, in its original Egyptian context the [Montecitorio]

obelisk celebrated the divine rights of the king while honoring the Sun god who

bestowed those rights on him". For the Montecitorio

Obelisk see also Habachi 2000, 75-76, Figs. 70; 72; 78; p. 75: "Sein

Material ist Rosengranit und der Koloß weist heute noch die stolze Höhe von

21,79 m auf - ursprünglich dürfte er jedoch noch höher gewesen sein", p.

106, Kat. 4: "Gew.[icht] ca. 214 t[ons]". Haselberger

2014c, 16 [2011], writes: "Restored to its original height of c.[irca] 21,80 m with material from the

collapsed Column of Antoninus Pius nearby"; cf. Haselberger 2014d, 189-190

with ns. 63-67; Herklotz 2007, 223-228; cf. infra,

n. 38. Cf. La Rocca 2014, 121-125,

131, 133, 136, 137, 138, 141, 143-145, 148, 150, 151, 155-158.

[27] cf. Häuber 2014, 714 with ns. 219, 220: "Because Commodus was the

Roman emperor, his subjects could duly expect from him the constant gift of abundantia [`abundance´], as J. Rufus

Fears [i.e., FEARS 1999, p. 169] explains the expectations expressed in the

iconography of our bust (Fig. 17 [here Fig.

6]), which are indicated by the fruit-laden cornucopiae [with further references]". Fears himself does not

discuss the possible cause for those expectations, as I try to do in this

contribution; cf. next note.

[28] cf. the publications by the Egyptologist Jan Assmann 1989-2006. I thank

the Egyptologist Rafed El-Sayed for the references. For relevant verbatim quotations from Assmann 2006,

cf. Appendix 3, infra, p. 418ff.

[29] Amenta 2008, 72;

Häuber 2014, 735 with n. 58.

[30] Brenk 1993, 154;

Häuber 2014, 735 with ns. 60, 61; cf. Carola Vogel, in: Habachi 2000, p. 117

with ns. 14, 15: "Exkurs 3: Neuere Forschungen, 7. Forschungen, die der

kultischen Aussage von Obelisken nachgehen", quoted verbatim in Appendix 4, infra,

p. 424ff.

[31] cf. Hölbl 2004b, 531; Häuber 2014, 153 with n. 21, p. 735 with n. 62.

[32]

My thanks are due to the Egyptologist

Konstantin Lakomy for pointing the latter fact out to me. Cf. Herklotz 2014, 221,

remarks on the function which has been attributed to obelisks in Pharaonic

Egypt: "Martin sieht in ihnen die Wechselwirkung zwischen Erde und Himmel

verdeutlicht, die zum Gedeihen des Landes erforderlich und für deren

Funktionieren der König zuständig war", with n. 595, quoting: Martin 1977,

24, 201. For the meaning of the obelisks, infra, n. 46. Pollini 2017, 64, writes: ""An auspicious

future is to be expected under the guidance of Augustus, appearing in the

exterior friezes [of the Ara Pacis] with his family and the pious leaders of

the state. With their assistance, Augustus has achieved the correct

relationship with the gods, what the Romans called the pax deorum ("peace of the gods"), which was essential to

the realization of the Pax Augusta, the very concept embodied in the Ara Pacis

Augustae"".

[33] cf. Goyon 1988, 29-30; id. 1989, 33-34; Häuber 2014, 733-735; Assmann

2006, 226-228; cf. infra, ns. 204,

205.

[34] cf. Häuber 2014, 716 with n. 240 and Fig. 17d on p. 43, quoting Zanker

2006, 325, caption of Fig. 240: "... Il ritratto di Augusto era munito di

una corona di raggi. Le cornucopie indicano in lui l'artefice della prosperità

universale". Cf. the Comments by Walter

Trillmich, infra, p. 727.

[35] Zanker 2006, 333-34; Häuber 2014, p. 716 n. 240.

[36] cf. Häuber 2014, 716 n. 240: ""ZANKER 2006, p. 325, caption

of Fig. 240 [on the altar, here Fig. 2];

cf. p. 334, caption of Fig. 247: "Altare da un santuario per la gens Augusta, eretto a Cartagine dal

liberto P. Perellio Edulo. Roma con la Vittoria davanti a un monumento che

celebra la pace e la prosperità universale. Prima età imperiale"; pp.

333-334 on the same relief of this altar: "un strano >monumento<, formato

da un globo, da una cornucopia e da un caduceo ... La composizione va intesa

come una versione semplificata di quelle che è, sull'Ara Pacis, la coppia Roma-Pax,

dove il secondo termine è rappresentato dagli oggetti - simbolo della pace e

del benessere universale""; cf. id. 1987, p. 304, Fig. 240; Schneider

1997, 111 with n. 103 (with further references), Taf. 10.1; Pollini 2012,

229-231, Fig. V.20; cf. Figs. V.19a; V.21.

[37] My assumption `nobody doubts ...´ was wrong: according to M. Schütz

2014a, 50 [2011], the Ara Pacis Augustae

has not as yet correctly been identified (!). This was refuted by La Rocca

2014, 124-125. Also H. Lohmann 2002, 52 doubts that the identification of the

building discussed here with the Ara Pacis is correct. For a discussion of

earlier doubts, cf. J.C. Anderson 1998, 29 with n. 8. For the Ara Pacis and the

settlement of the western provinces, cf. Hannah 2014, 110 and infra, n. 216. So already Buchner 1982,

10 (= id. 1976, 322), and I. Romeo 1999. R. Billows 1993 has convincingly

identified the procession, shown on the Ara Pacis, as a supplicatio; cf. I. Romeo 1999, 341 with n. 1, and passim. For the supplicationes on January 30th, La Rocca 2010, 220; cf. infra, n. 48.

[38] cf. Pollini 2017, 60-61: "These solar alignments bring to mind

Augustus' special relationship with Apollo, especially Apollo Palatinus, with

his strong solar aspect, which is discussed below by Galinsky (section 9). This

phenomenon also played off Augustus' birth, since another very important Temple

of Apollo, that in Circo Flaminio

(also known as the Temple of Apollo Sosianus), was rededicated on Augustus

birthday", with n. 119.

[39] All this is discussed by many contributors to Frischer et al. 2017: Jackie Murray 2017; Karl

Galinsky 2017; John F. Miller 2017; Frischer 2017, 76, 77. See also Herklotz

2007, 215-217 with n. 550.

[40] cf. Häuber 2015, p. 7; ead.

forthcoming. Contra: K. Galinsky

2017, 65 with n. 135; and Filippo Coarelli in his Contribution in this volume,

cf. infra, p. 667ff.

[41] Wiseman 2012a-2014b; and Wiseman forthcoming2.

[42] cf. Claridge 1998, 128-134; ead. 2010, 135-144; Claridge 2014.