Chrystina Häuber (2023): The major results of this book on Domitian

(preview from FORTVNA PAPERS 3)The

first part of this summary is dedicated to the Cancelleria Reliefs, which were

commissioned by Domitian. Concerning their interpretation, I follow Filippo

Magi (1939; 1945) and hope to be able to disprove the arguments of those recent

scholars, who have rejected his hypotheses. I hope to further support Magi's

ideas with some new evidence that has led me to suggest that these panels had

originally decorated the passageway of one of Domitian's arches on the Palatine.

Likewise new is the idea, pursued in this study, to compare the contents,

visualized on the Cancelleria Reliefs with those, represented on the pyramidion of the Pamphili Obelisk/

Domitian's obelisk on display on top of Gianlorenzo Bernini's `Fountain of the

Four Rivers´ in the Piazza Navona at Rome, and with the contents, formulated expressis verbis in the hieroglyphic

texts of his obelisk. We shall see that in both monuments stress is layed `on

the legitimation of Domitian's reign as emperor´. Then follows a short summary

of the results obtained in this study, which concern Domitian's building

projects at Rome. From this emerges that Domitian (or rather: all three Flavian

emperors together) have caused the effect, `that Rome is still nowadays basically

a Flavian city´. A third, much larger part of this summary is dedicated to

Domitian's Palace on the Palatine, his Domus

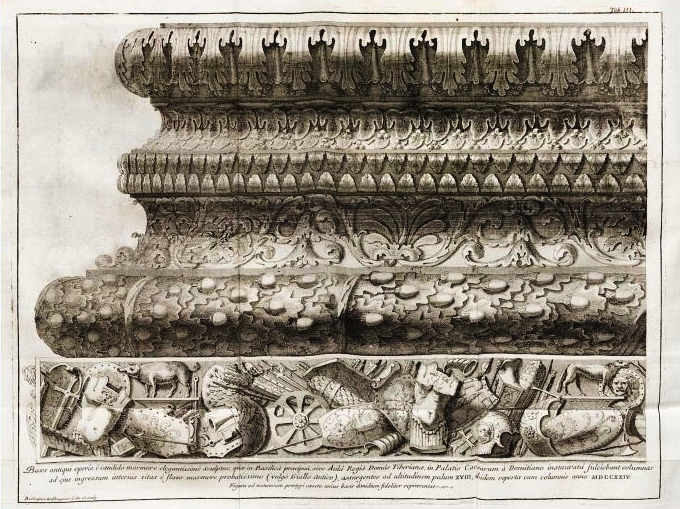

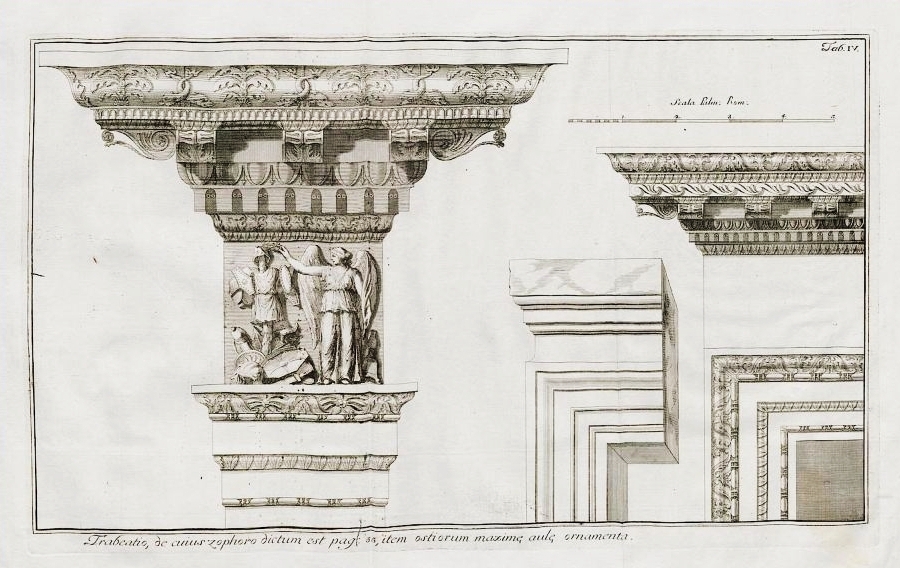

Augustana, concentrating on some of the finds, which Francesco Bianchini

had excavated in the `Aula Regia´,

published posthumously in 1738. The chosen artworks demonstrate ``Domitian's

claim to possess the virtus

`invincibility´´´, that `was on principle expected from all Roman emperors´ and

which, in its turn, `guaranteed Rome's wealth´.

The just-mentioned statements in inverted commas are quotes from scholars, who

will be discussed in the following text.

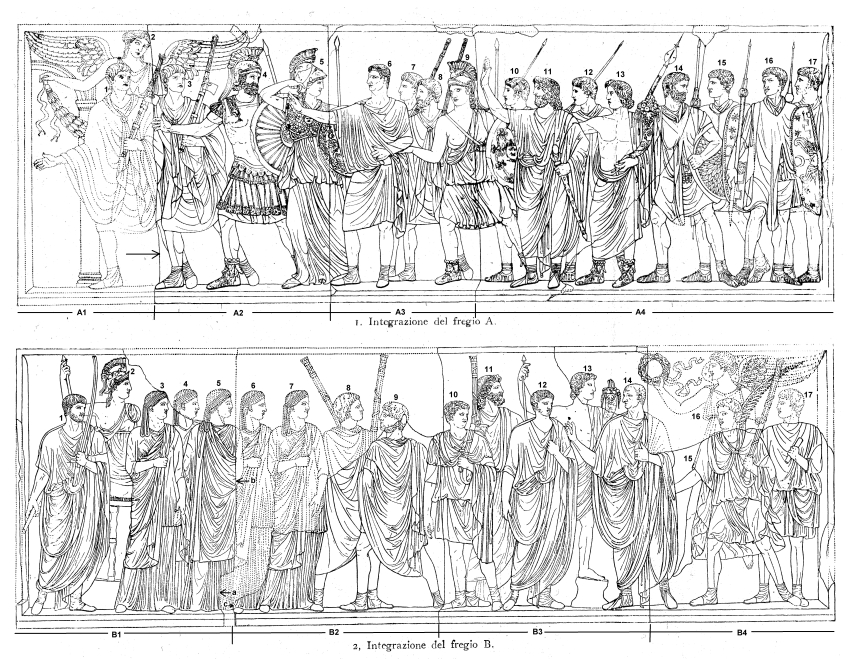

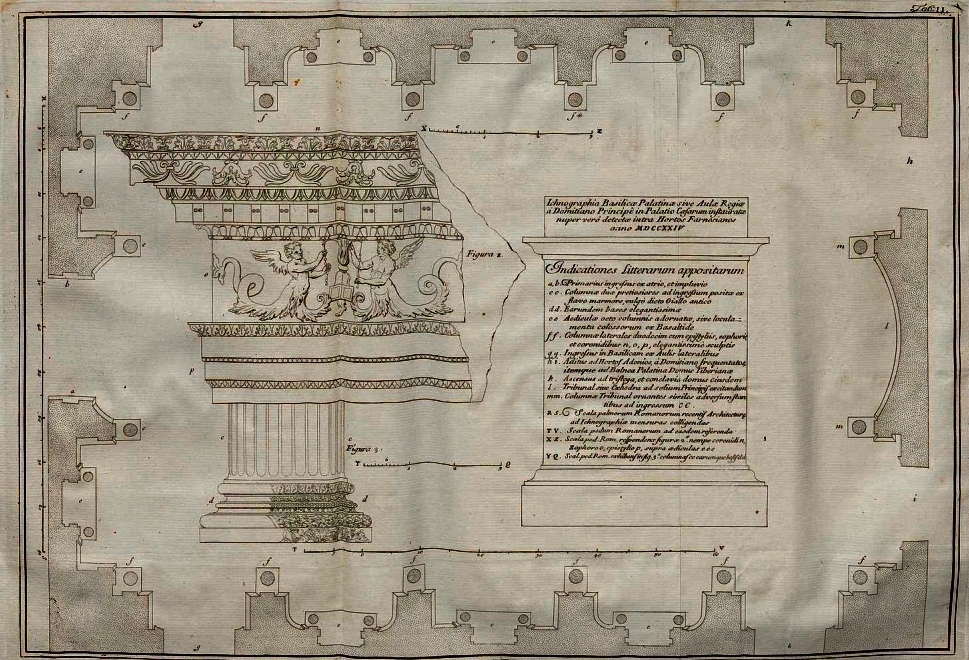

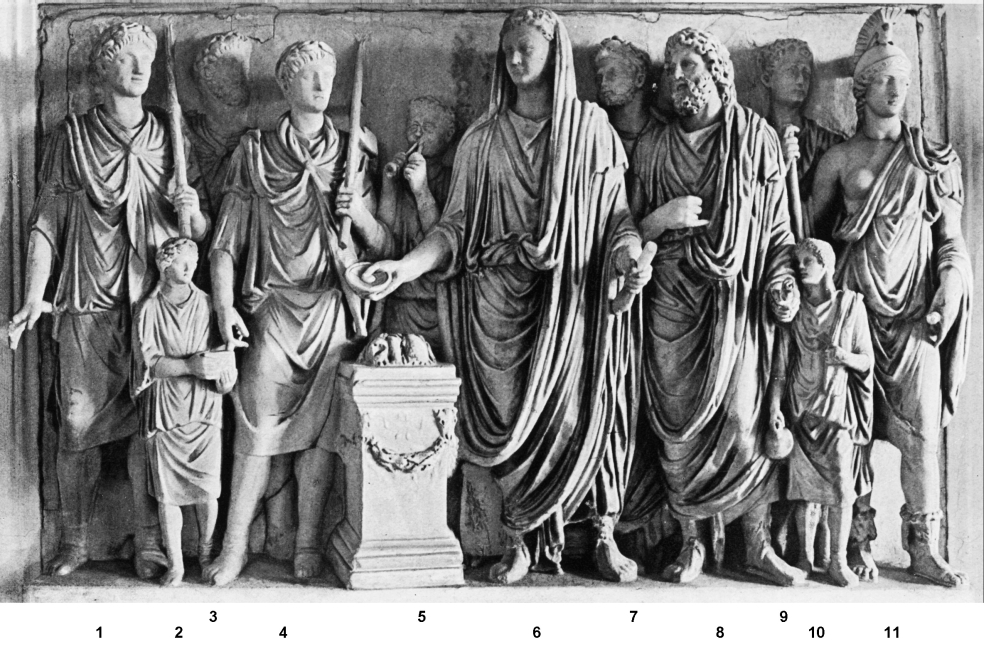

Figs. 1 and 2 drawing. F. Magis drawing of Frieze A and B

of the Cancelleria Reliefs, with numbering of slabs and represented figures.

From: F. Magi (1945, Tav. Agg. D 1 and

2). The slabs of both panels (A1-A4 and B1-B4) and the figures of both Friezes

(1-17) are numbered, as in S. Langer and M. Pfanner (2018, 19, Abb. 2).

Magi's

two drawings show his reconstruction of the Cancelleria Reliefs; cf. F. Magi

(1945, Tav. I), the display of the reliefs at the Musei Vaticani, Museo

Gregoriano Profano, follows Magi's reconstruction. This display has been

documented by the photographs here Figs.

1 and 2 (our Figs. 1 and 2 are not illustrated here).

I follow here Magi's reconstruction (1945) of the

Cancelleria Reliefs, which is the most important prerequisite for our

visualization of Figs. 1 and 2 of the Cancelleria Reliefs, drawing,`in situ´ (cf. infra).

My thanks are due to Giandomenico

Spinola and Claudia Valeri of the Vatican Museums, together with whom I could

study the Cancelleria Reliefs in front of those panels on 24th September 2018,

and on 8th March, 9th May and 19th September 2019. We found out that S.

Langer's and M. Pfanner's (2018, 29-31, Taf. 10,1, Abb. 7a; 7b, pp. 50, 52-53,

68, 70) assumption of an additional slab between B1 and B2 on Frieze B is based

on a number of errors: these errors concern some technical properties of the

slabs B1 and B2, as well as misunderstandings of Magi's (1945) description of

the Vestal Virgins on slabs B1 and B2. Langer and Pfanner (2018, 29, 73, 76)

themselves regard their assumption that all six Vestal Virgins should be

represented on frieze B as a support of their hypothesis.

Ranuccio Bianchi

Bandinelli (1946-48, 259) remarked on Frieze B that usually only five Vestal

Virgins (as represented on Frieze B) could participate in public ceremonies,

because the sixth Vestal Virgin had always to stay behind to keep the fire of

Vesta going. I have, therefore, asked the religious historian Jörg Rüpke,

whether this is reported by ancient literary sources, and how many Vestal

Virgins we might expect to have usually appeared in public ceremonies. Jörg

Rüpke was kind enough to answer my questions, and comes to the following

conclusion: "Kurzum, denkbar ist die Pflicht, dass eine stets Feuerwache

hatte" (`In short, it is conceivable that one [of the six Vestal Virgins]

had always to watch the fire´). In addition to this, Rüpke has kindly allowed

me to publish his E-mail as his first Contribution

to his volume. Cf. The first Contribution

by Jörg Rüpke in this volume on the question, how many Vestal Virgins we might

expect to appear at public ceremonies, such as the one shown on Frieze B of the

Cancelleria Reliefs (cf. here Fig. 2).

Giandomenico Spinola, Claudia Valeri and Jörg

Rüpke have thus greatly supported my efforts to verify Magi's reconstruction of

the length of Frieze B of the Cancelleria Reliefs.

Cf. infra, at Introductory

remarks and acknowledgements; and at Chapter V.1.d. The reconstruction, in

my opinion erroneous, of the length of Frieze B by S. Langer and M. Pfanner

(2018) and the correct reconstruction of the length of Frieze B by F. Magi

(1945), whom I am following here (cf. here Figs.

1; 2; Figs. 1 and 2 drawing; and

Figs. 1 and 2 of the Cancelleria

Reliefs, drawing,`in situ´).

With a discussion of how many Vestal Virgins we might expect to appear at

public ceremonies, such as the one shown on this panel, and with The first

Contribution by Jörg Rüpke.

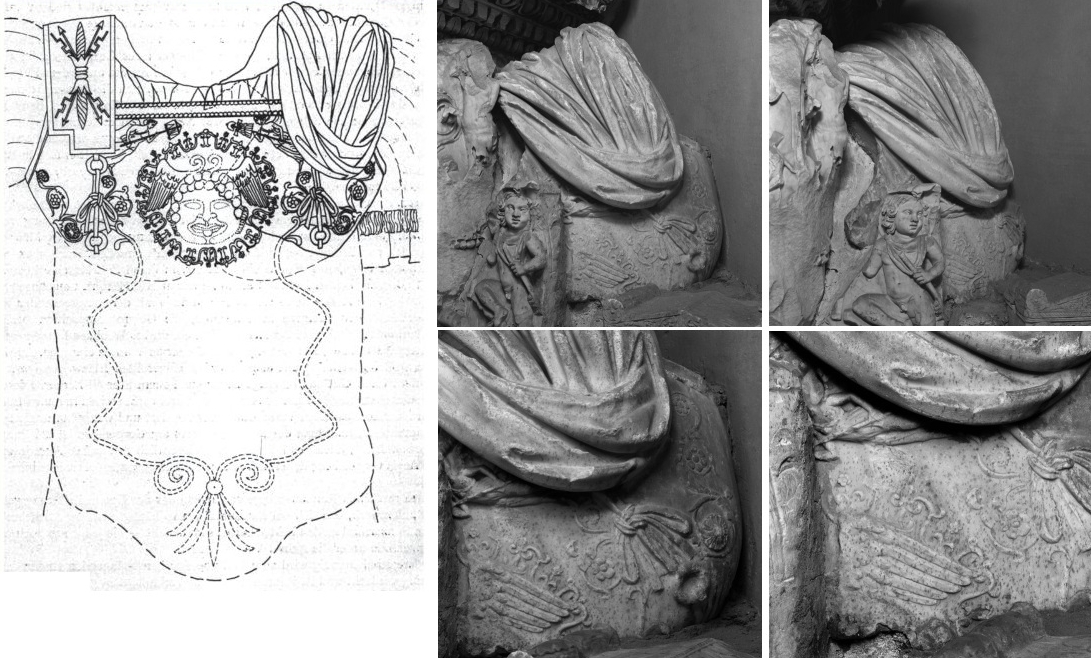

Claudia Valeri and Giandomenico helped me also in solving the

vexed problem, whether or not the head of Vespasian on Frieze B (cf. here Figs. 1 and 2 drawing: figure 14) is

the result of a reworking process. This had first been suggested by Marguerite

McCann (1972, 251 with n. 8; cf. infra,

at n. 111, in Chapter I.1.), and later by Marianne Bergmann

(1981, 24, infra, at ns. 111, 115, 190, in Chapter I.1.),

whose hypothesis has been followed by many scholars (cf. infra, at Chapter I.1.1.).

Stephanie Langer and Michael Pfanner (2018, 60 with ns. 49-52; cf. infra, at Chapter V.1.h.1.) state that both McCann's (1972) and Bergmann's (1981)

hypotheses have been rejected. According to Bergmann's hypothesis (1981, 23-24,

Taf. 11; 12; 9, p. 25), the emperor on Frieze B had originally been Domitian,

whose head was allegedly reworked into the extant portrait of Vespasian.

Langer and

Pfanner have contributed new observations to this discussion which, in their

opinion, prove that originally the emperor on Frieze B had been Domitian (cf. id. 2018, 57-58, 72-74, Abb. 22-24; Abb.

23: they demonstrate their observations by illustrating a photo of Vespasian's

neck after a plaster cast, but note that all the details indicated by them look

different on the original relief; cf. their Kapitel 2.9.4). Cf. infra, at Chapter V.1.h.2.

To show the results obtained by Giandomenico Spinola, Claudia

Valeri and myself, when studying together Vespasian's neck in front of Frieze B

of the Cancelleria Reliefs, I anticipate in the following a text passage that

was written for Introductory remarks and

acknowledgements:

`The other detail I wanted to study again on

9th May 2019 in front of the original was the neck of the emperor on Frieze B.

Langer and Pfanner (2018; cf. infra,

at Chapter V.1.h.2.)) assert that

Vespasian's larynx cuts through a wrinkle at the represented man's neck, an

alleged fact, which in their opinion proves that this wrinkle belongs to a

presumed earlier portrait, and that Vespasian's larynx was only carved at a

second moment. Langer and Pfanner, therefore, conclude that Vespasian's entire

head has been recut from this alleged earlier portrait. Their conclusion is

based on a wrong observation though: in front of the original is clearly

visible - with and without the aid of a lamp - that the wrinkle in question was

instead cut after the larynx was

sculpted. What we see is, therefore, the first and only larynx ever carved on

this figure's neck - a fact, which proves beyond any doubt that the extant

portrait of Vespasian is the original head of the emperor on Frieze B (cf. infra, at ChapterV.1.h.2.)).

Consequently, also Magi's assumptions

concerning the head of Vespasian prove to be correct, which he took for the

original head of the represented emperor on Frieze B (cf. id. 1939, quoted verbatim

infra, in n. 112, at Chapter I.1.; and id. 1945) [my emphasis]´.

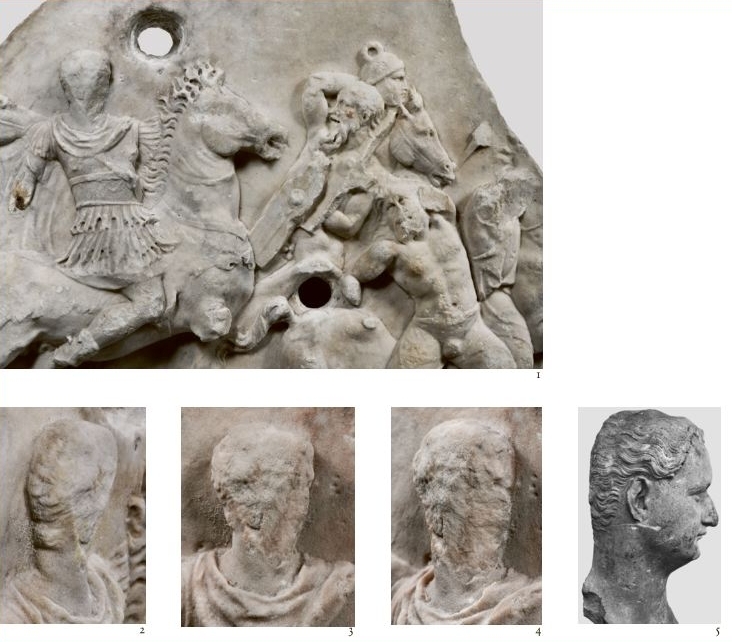

Fig. 1. [here not illustrated photo]

Città del Vaticano. Musei Vaticani. Frieze A of the Cancelleria Reliefs. Profectio of Domitian in AD 83, 89 or

92. After the emperor's assassination and damnatio

memoriae, Domitian's face on Frieze A (figure

6) has been reworked into a portrait of the Emperor Nerva. Therefore, the

panel now probably represents Nerva's (alleged) profectio to his bellum

Suebicum in AD 97. Cf. infra, at

Chapters I.-VI.; especially n. 232,

in Chapter I.2.), and Chapters II.3.1.a); II.3.3.a). See also Appendix

IV.d.2.e); Appendix IV.d.2.f): in

my opinion, this relief represents Domitian's profectio: of AD 89; and in Chapters II.3.1.a); II.3.2.; V.1.b); V.1.c): for Nerva's motivation to usurp this profectio relief of Domitian.

Fig. 2. [here not illustrated photo]

Città del Vaticano. Musei Vaticani. Frieze B of the Cancelleria Reliefs. Adventus of Vespasian at Rome in the 1.

half of October of AD 70, his coronation with the corona civica for having ended the civil war AD 68-69, and his investiture as the new Roman emperor.

The fact that Vespasian lays his lifted right hand on the left shoulder of

Caesar Domitian, who is standing right in front of him, means the legitimation

of Domitian's future reign.

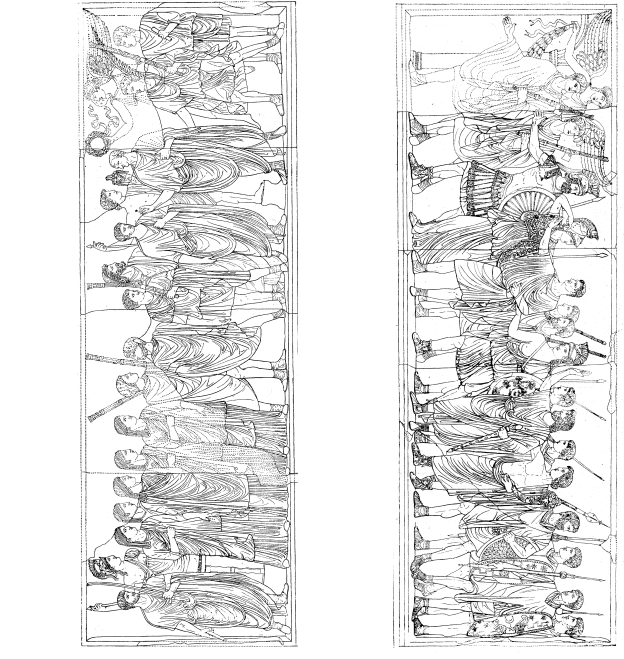

Figs. 1 and 2 of the Cancelleria Reliefs, drawing,`in situ´. Visualization created on the

basis of F. Magis drawings (1945), here `Figs. 1 and 2 drawing´.

Based on hypotheses, suggested by A.M. Colini (1938,

270), H. Kähler (1950, 30-41), J.M.C. Toynbee (1957, 19), J. Henderson (2003,

249), and especially M. Pentiricci (2009, 61-62; cf. infra, ns. 262, 263, 264, in Chapter

I.3.2.), this visualization intends

to show the Cancelleria Reliefs, as if attached to the opposite, parallel walls

in the bay of an arch, built by Domitian. It made only sense to try this

reconstruction, because both panels certainly belonged together, a fact, which

is inter alia proven by their equal

heights. Since it is debated over which kind of building those panels may have

belonged, we wanted to know, whether or not the compositions of both friezes

were designed in order to stress relationships among the figures appearing on

both panels, once mounted on opposite walls and viewed together. The

prerequisite for this kind of inquiry was the correct positioning of both

friezes, when both were attached to opposite walls in the bay of an arch. We

knew that this could, in theory, be done for two reasons: a) both friezes were originally framed on all sides by identical

projecting ledges; b) these

projecting ledges are partly preserved on the right hand small side of Frieze A

and partly on the left hand small side of Frieze B. We could, therefore, mount

(first, in 2020, the photographs, here Figs. 1; 2), now the drawings of both

panels, used for this operation by basing our reconstruction on this common

axis of those two small sides of the panels which, in our reconstruction, now

stand opposite each other. (In this illustration of our reconstruction those

two small sides of both panels appear at the bottom of the page). For our

reconstruction we used (first the photographs of Frieze A and B of the Vatican

Museum, here Figs. 1 and 2, both of which follow Magi's reconstruction of

1945), now Magi's own drawings (1945) of both Friezes. In our visualization,

these (first the photos), now the drawings are `lying on their backs´ in order

to show, how an ancient beholder, passing through the bay of this arch, would

have seen both panels. Both visualizations demonstrate a) that the beholder who passed through this bay must have had the

impression of `moving together´ with the processions that are depicted on both

friezes; and b) that there is indeed

one such relationship amongst those two panels that we were looking for. The

figures in question are the Emperor Domitian (now Nerva) on Frieze A (figure 6)

and the togate youth on frieze B (figure 12) - when both panels are in situ, these two figures stand almost

opposite each other. Prior to our reconstruction, this fact had not been

observed. And because both figures are heading the two processions `that are

moving on these panels together with the beholder in the same direction´ these

two figures turn out to be the most important persons on both panels. Both

facts support the assumption that the Cancelleria Reliefs had been the

horizontal panels in the bay of one of Domitian's arches. Considering also that

Domitian commissioned the structure in question, both facts support at the same

time the hypothesis suggested here that the togate youth on Frieze B may be

identified as the young Caesar Domitian, who is represented on Frieze B in his

capacity as praetor urbanus.

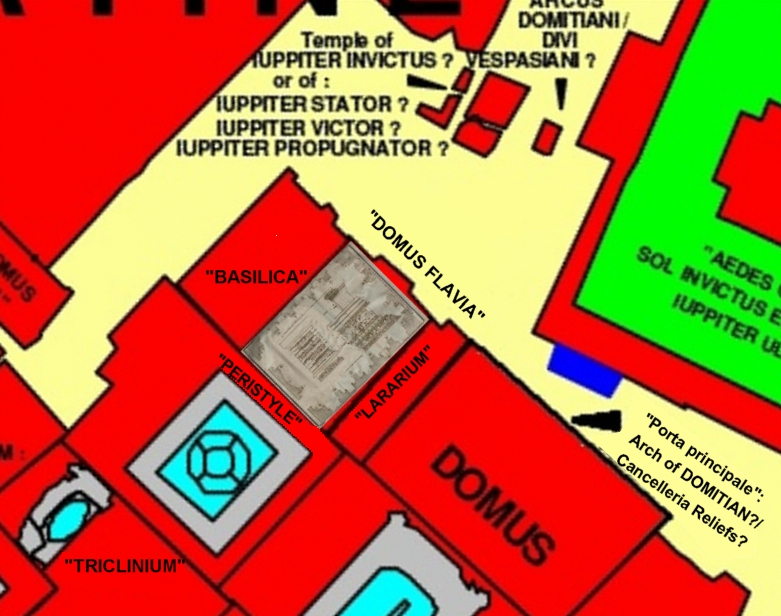

I tentatively suggest, in addition to this, that the

Cancelleria Reliefs may have decorated the bay of the `Arcus Domitiani´, which stood on the Palatine, in front of

Domitian's Palace Domus Augustana and

which, according to F. Coarelli (2009b, 88; id.

2012, 481-483, 486-491), Domitian may have dedicated to his father, Divus Vespasianus; or rather one of the

three bays of the Arch of Domitian, which Coarelli assumes at the "Porta

principale" of Domitian's Domus

Augustana. Coarelli identifies this arch with the Pentapylon, believing that this was a triumphal arch (for the

location of both arches; cf. here Fig. 58).

F.X. Schütz and C. Häuber 2022, reconstruction (cf. infra, at Chapters I.3.2.; II3.1-d); Section VII.; V.1.d); V.1.h.1.); V.1.i.3.);VI.3.; Addition; Appendix IV.d.2.f); Appendix

IV.d.4.b)).

Fig. 28. Obeliscus Pamphilius/ Domitian's Obelisk. From

the Iseum Campense. On display on top of Gianlorenzo Bernini's `Fountain of the

Four Rivers´ in the Piazza Navona at Rome (photo: F.X. Schütz 5th September

2019).

In my

earlier study on Domitian's obelisk (2017), I had come to the following

conclusion:

"In

the course of studying the Iseum Campense,

some new arguments have been found, which, in my opinion, support the old

assumption that Domitian had actually commissioned his Obelisk for this

sanctuary, that is now on display on top of Gianlorenzo Bernini's famous

Fountain of the Four Rivers in Piazza Navona [cf. here Fig. 28] ... In one of the inscriptions on his Obelisk, [the text

is Egyptian,] written in hieroglyphs, Domitian formulates his hope that his

contemporaries as well as posterity will always remember the achievements of

his family, the Flavian dynasty, especially their benefactions for the Roman

People. Domitian stresses that his family managed to consolidate the state,

which had severely suffered from those `who reigned before´ (i.e., the emperors of the Iulo-Claudian

dynasty)"; cf. Häuber (2017, 21; cf. pp. 158-168 for Domitian's obelisk

and its inscriptions, my quote on p. 21 is inter

alia based on K. LEMBKE 1994 and J.-C. GRENIER 2009). Cf. infra, n. 466, in Chapter IV.1., for those references in detail.

For the pyramidion and the texts of Domitian's obelisk see also E.M.

Ciampini (2004, 156-167; id. 2005,

published again, infra, in Chapter IV.1.1.d); see also the complete Chapter

IV. Frieze B of the Cancelleria Reliefs

(cf. here Fig. 2) and the Obeliscus

Pamphilius/ Domitian's obelisk (cf. here Fig.

28), especially Chapter IV.1.1.a)

- IV.1.1.h); and at Appendix II.a-e). Again on the Egyptianizing

marble relief allegedly from Ariccia at the Museo Nazionale Romano, Palazzo

Altemps (Fig. 111) - a

representation of the Egyptian festival of New Year?

As

mentioned above, in this new study, the contents of Domitian's obelisk (of the

reliefs represented on its pyramidion

and of its hieroglyphic inscriptions) are compared with the contents of Frieze

B of the Cancelleria Reliefs, which were likewise commissioned by Domitian. In

my opinion, both monuments express very clearly the same political message, and

in addition to this, how Domitian saw himself.

Concentrating predominantly on

Domitian, this study tries to answer the question, why Domitian felt the

desperate need to build `in such a pharaonic manner´, as has (similarly) first

been suggested by Mario Torelli (1987, 575, quoted verbatim in this study, in n. 228, at Chapter I.2.). This notorious characteristic of Domitian has aptly been called

"Bauwut" (`building rage´) by Stephanie Langer and Michael Pfanner

(2018, 41 with n. 23); cf. infra, in n. 480,

at Chapter VI.3.; and discussed in Appendix IV.d.4.b) Domitian's building

project comprising the Campus Martius,

the Capitoline Hill and the sella

between Arx and Quirinal. With

detailed discussion of the Templum Pacis.

Of

course, Domitian's building policy has already been studied by many previous

scholars. Personally I favour the following observations:

Eric M. Moormann (2018, 162) mentions

"three fields of interest in Domitian's building policy", as defined

by Jens Gering (2012, 210-211): "personal grandeur, family memory and

legitimization".

This is exactly how, in my opinion,

also the contents of Frieze B of the Cancelleria Reliefs can be defined. And

when we study the contents of Domitian's obelisk, we arrive, in my opinion, at

exactly the same result.

To

illustrate this last assertion, I will give you an example from one of the

hieroglyphic inscriptions of Domitian's obelisk, and will compare that with the

content of Frieze B of the Cancelleria Reliefs. In my opinion, the subject of

both is Domitian's legitimation as emperor, which he has received from his

father Vespasian (and from his brother Titus).

But there are two important differences:

whereas on Frieze B of the Cancelleria Reliefs Vespasian is represented as

still being alive, in the hieroglyphic text on Domitian's obelisk he is called Divus Vespasianus; and, contrary to

Frieze B, on which Titus does not appear (being at Jerusalem at that stage),

this hieroglyphic inscription declares that Domitian has received his reign of

the Empire also from his elder brother Divus

Titus.

It goes

without saying that in the case of Frieze B of the Cancelleria Reliefs any

interpretation of the represented scene depends on the identification of its

two protagonists. I myself follow Filippo Magi (1939; 1945) in identifying

those figures with the Emperor Vespasian and his younger son Domitian (cf. here

Fig. 2; Figs. 1 and 2 drawing: figures:

14; 12).

I

regard the hypothesis, according to which not only this hieroglyphic

inscription on Domitian's obelisk, but also the iconography of Frieze B of the

Cancelleria Reliefs prove that Domitian ordered the relevant people involved in

creating those artworks to address his legitimation as emperor, as the most

interesting result of my book on Domitian. I have, therefore, chosen the

following title for this study:

The Cancelleria Reliefs and Domitian's Obelisk in Rome in

context of the legitimation of Domitian's reign. With studies on Domitian's

building projects in Rome, his statue of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus,

the colossal portrait of Hadrian (now Constantine the Great), and Hadrian's

portrait from Hierapydna in Honour of Rose Mary Sheldon.

For

those, who wonder, why the Emperor Hadrian appears likewise in the title of

this study on Domitian: you will see that only by studying those subjects

related to the Emperor Hadrian, have I managed to find important facts

concerning Domitian. The study of the

colossal portrait of Hadrian (now Constantine the Great in the Palazzo dei

Conservatori; here Fig. 11) led to

the identification of the statue-type of Domitian's (fourth) statue of Iuppiter

Optimus Maximus Capitolinus (cf. here Fig.

10), and the study of Hadrian's statue from Hierapydna (here Fig. 29), via Hadrian's military campaigns, to Domitian's Dacian Wars and,

finally, to my dating of the Cancelleria Reliefs. The latest additional study I

have conducted, that on Hadrian's Temple complex in the Campus Martius, resulted in the (for me) surprising finding that

Domitian's prevailing bad image has been `commissioned´ by Trajan. I

anticipate, therefore, in the following a relevant passage from Introductory remarks and acknowledgements:

`Studying Hadrian's military

campaigns ... has also provided new insights concerning Domitian's Dacian Wars,

and has procured the answer to the question for which of his military campaigns

Domitian (now Nerva) is actually leaving for on Frieze A of the Cancelleria Reliefs

(cf. here Fig. 1; Figs. 1 and 2 drawing:

figure 6). Another result consists in the identification of the colossal

statue of Jupiter in the Hermitage at St. Petersburg (cf. here Fig. 10) as a copy of the colossal

(chryselephantine?) cult-statue of Jupiter in Domitian's (fourth) Temple of

Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus. This statue-type of Jupiter (and its

variants) was extremely successful in antiquity and has also been copied in

statuette format as Capitoline Triad, together with Juno and Minerva (cf. here Fig. 13). Most famous among these

copies in statuette format is certainly the statuette of `Euripides´ in the

Louvre at Paris (cf. here Fig. 12).

As Hans Rupprecht Goette (forthcoming) has demonstrated, this was created at

the order of Franceso Ficoroni by turning such a headless copy of Jupiter of a

Capitoline Triad into the tragic poet.

I am not saying that it would have

been impossible to find out those new data about Domitian's military campaigns

or concerning his cult-statue of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus

otherwise, but, as a matter of fact, I found them this way´.

See also the title of the latest

study added to this book:

Chapter

I.2. The consequences of Domitian's

assassination:

Nerva is forced to adopt Trajan and Trajan creates

Domitian's negative image to consolidate his own reign. With Hadrian's adoption

manquée in October of AD 97, his 20-year

long road to his accession and his thanksgivings for it, his Temple complex in

the Campus Martius ...

Let's now begin with the hieroglyphic text on Domitian's

obelisk that I have mentioned above.

Cf.

Emanuele M. Ciampini (2004, 163-164). In the following quotation, I have left

out Ciampini's drawing of the relevant hieroglyphic inscription and his

transliteration of this Egyptian text, but quote only his Italian translation

of it:

"Lato

verso Corso Rinascimento (est)

Pyramidion

- Domiziano di tronte [corr.: fronte]

a Mut, seguito da un'altra figura

H22 Horo [i.e.,

Domitian]: Quello per il quale dei e uomini fanno lode;

H 23 quando riceve la regalità da suo padre Vespasiano il dio, [page 164]

H 24 dal fratello maggiore Tito il dio, mentre il suo ba si muove verso la volta celeste [the

emphasis is by the author]".

Let's now turn to Frieze B of the Cancelleria Reliefs.

In the following,

I anticipate a text, written for Chapter I.2.

The consequences of Domitian's assassination .... Introduction; Section I. The

motivation to write this Chapter: ... and the subjects discussed here, as told

by the accompanying figures and their pertaining captions.

The

following text refers to our Rome map here Fig.

58.

`3.) Vespasian's 500 kilometre walk (?) on

the Via Appia from Brindisi to Rome,

where he arrived in the 1. half of October AD 70 at the Porta Capena in the Servian city Wall (cf. here Figs. 2; 58).

Vespasian's

itinerary is likewise discussed in this study on Domitian, because I suggest

that Frieze B of the Cancelleria Reliefs (here Fig. 2; Figs. 1 and 2 drawing: figure 14) shows Vespasian who,

coming back from Alexandria, and especially after this 500 kilometre journey on

the Via Appia, all the way from

Brindisi, has just arrived at his destination, the City of Rome.

There he is solemnly received by the

representatives of the City (from left to right): the city goddess Dea Roma, five Vestal Virgins, the Genius Senatus, the acting praetor urbanus (i.e., his son, Caesar Domitian) and the Genius Populi Romani. This panel shows at the same time how

Vespasian arrived for the first time as emperor at Rome or, in other words, his

adventus into Rome, which, as we now

know, had occurred in the 1. half of October in AD 70´. - For this date; cf. infra, at n. 195, in Chapter I.1.1. In the following, I will explain

my just-quoted interpretation of this scene in detail.

In my

opinion, the emperor on Frieze B (Fig. 2; Figs. 1 and 2 drawing: figures 14;

12), and the togate youth standing in front of him, were from the very

beginning the Emperor Vespasian and his son Domitian

I thus

follow Filippo Magi's (1939, 1945) interpretations of the two major figures on

Frieze B (cf. here Fig. 2; Figs. 1 and 2

drawing: figures 12; 14), and hope to be able to support in my book Magi's

hypotheses with further facts. Apart from Diana E.E. Kleiner (1992, 191, Fig. 158, quoted verbatim supra,

at n. 394, in Chapter III.),

Stefan Pfeiffer (2009, 62, quoted verbatim infra, as epigraph of Chapter V.1.i.3.)), as well as John Pollini

(2017b, 115-118, cf. infra, n. 72,

in Chapter I.1.), as well as

Giandomenico Spinola and Claudia Valeri (both Musei Vaticani); cf. infra, at Introductory remarks and acknowledgements; and at The Contribution by Giandomenico Spinola

in this volume (quoted below), who likewise follow Magi, most other scholars

have rejected Magi's relevant hypotheses and we shall see in this study that it

will take some time to prove all the arguments of those scholars wrong.

Two of the arguments against Magi's

interpretation that Frieze B shows Vespasian's adventus in AD 70, has always been that those scholars could only

imagine Vespasian in military garb, and accompanied by members of his

victorious army, since he was at that stage coming back from his victories in

the Great Jewish War. But precisely that was not true. I anticipate, therefore,

a passage written for Chapter V.1.i.3.):

`...

according to Cassius Dio 65,10, Vespasian, as soon as he had landed in Italy at

Brundisium (Brindisi) in AD 70, had changed from military into civilian garb -

this is at least how Jocelyn M.C. Toynbee (1957, 4-5 with n. 1 on p. 5; cf. supra, at n. 201, in Chapter I.1.1.) and Elisabeth Keller (1967, 211;

cf. infra, at n. 415, in Chapter III.), in my opinion convincingly, have

interpreted this passage; Cassius Dio tells us also that Vespasian went from

Brindisi to Rome. This means, by the way, that Vespasian has come down the Via Appia, and that, therefore, Frieze B

is set at the Porta Capena in the

Servian city Wall [cf. here Fig. 58]

- without picturing this gate.

That Vespasian is shown on Frieze B

as wearing a tunica and a toga at the represented moment, is

therefore historical, as well as the fact that he came to Rome in October of AD

70; even the most bewildering feature of Frieze B is true: we also know that

Vespasian came back to Rome without his army (but see now above and infra, at Chapter V.1.i.3.a))´.

To the

just-quoted facts we may add an observation, made by Rita Paris (1994b, 81-83),

that she herself has also applied to the emperor, who is represented on Frieze

B of the Cancelleria Reliefs (cf. Fig.

2; Figs. 1 and 2, drawing: figures 14; 16). This emperor (figure 14) is crowned by Victoria (figure 16) with the corona

civica : an honour only bestowed upon Augustus and Vespasian, because both

had been able to put an end to a civil war. The emperor on Frieze B was

certainly not Augustus (this has, of course, so far no scholar suggested),

because the kind of toga he is

wearing became only fasionable under Domitian; cf. Hans Rupprecht Goette (1990,

40, 41, Taf. 12, 5), and because Vespasian is also represented as wearing the corona civica on one of the reliefs from

the Templum Gentis Flaviae (cf. here Fig. 33), also this emperor on Frieze B

must have been from the very beginning a portrait of Vespasian, as rightly

stated by Rita Paris (1994b, 82). I anticipate in the following the relevant

passage concerning Rita Paris's observation from infra, Introductory remarks

and acknowledgement:

`Besides,

Rita Paris (1994b) had already found long ago an argument that proves beyond

any doubt that the emperor on frieze B was from the very beginning Vespasian.

In her discussion of one of the marble reliefs of the Templum Gentis Flaviae, which shows, in my opinion, Vespasian's adventus into Rome in October of AD 70,

Paris mentions the corona civica

Vespasian is wearing on this panel (cf. infra,

in Chapter V.1.i.3.a) and here Fig. 33). Paris (1994b, 81-83), in her

description of this relief, stresses that the decoration with this specific

wreath was a) regarded by Pliny (HN

16,3) as "l'emblema più fulgido del valore militare" (`the most

splendid symbol of military prowess´), highly superior to the decorations with

all other known crowns granted for military victories, and b) that Vespasian had

been honoured this way because, by conducting his victorious campaigns, he had

put an end to the civil war of AD 68-69. - Exactly as Augustus before him, who

had received the corona civica for

likewise having ended a civil war (cf. infra,

at Chapter V.1.i.3.a) and here Fig. 35)´.

Some scholars have, in addition to this, asserted that Filippo

Magi was by no means first to realize that the emperor on Frieze B of the

Cancelleria Reliefs represents Vespasian, (erroneously) asserting that this had

been first published by `S. Fuchs 1938´, but without providing a reference.

Those scholars ignored the fact that, already in his article of 1939, Magi had

identified the emperor on Frieze B with Vespasian (cf. infra, n. 112, in Chapter I.1., where the relevant passage of F.

MAGI 1939, 205, is quoted verbatim).

My thanks are due

to Michaela Fuchs, who found this publication for me: it is

Siegfried Fuchs 1937: but the author did not mention the

Cancelleria Reliefs at all. Not surprisingly, because the slabs B3 and B4 of

Frieze B with the portrait of Vespasian should only be found in 1938 (cf. infra, n. 113, in Chapter I.1.)

For a discussion;

cf. infra, ns. 5; 113; 191, in Chapter I.1.,

especially at: The Siegfried-Fuchs-Saga. The entire story reminds me of a

famous book by Carl Robert, to which my late supervisor Andreas Linfert (15th

May 1942 -21st May 1996) had alerted me many years ago - the title of which has

become proverbial:

Archaeologische

Maerchen aus alter und neuer Zeit (1886)

(`Archaeological

fairy tales from old and new times´)..

Already

Magi (1945; like all later scholars) knew that the matter is further

complicated by some decisions, obviously made by Domitian, who commissioned the

Cancelleria Reliefs.

Our extant literary sources describe,

for example, in great detail Vespasian's arrival at Rome on that occasion; cf.

Cassius Dio (65,9-10) and Flavius Josephus (BJ 7,2; 7,4,1). But these authors a)

do not mention such a formal adventus

ceremony at Rome, nor do they b) mention Domitian in this context

at all (!). On the contrary, we know from those sources that the first

encounter of father and son (which seems to be depicted on Frieze B), after

four years of separation, had instead already occurred a couple of days (?)

before, at Beneventum. In reality, Domitian must, therefore, have been among

those people, together with whom his

father Vespasian had arrived on that occasion at Rome; for all that; cf. infra, at Chapter V.1.i.3.).

Contrary

to myself, most other scholars follow those, who have (in my opinion

erroneously) asserted that the head of this emperor (or even the heads of both

figures) on Frieze B have been reworked. I have discussed these scholarly

opinions in great detail (cf. infra,

in Chapters I.1.; I.1.1.; V.1.i.3.); VI.3.), in my opinion, these assertions

have caused a great deal of confusion. To the effect that currently most

scholars believe that Frieze B showed originally another emperor (most scholars

believe: Domitian), in addition, many scholars believe that the togate youth in

front of this emperor cannot possibly be a portrait at all.

Against Magi's identification of the

togate youth in front of the emperor of Frieze B with Domitian (here Fig. 2; Figs. 1 and 2 drawing: figure 12),

scholars have mentioned three arguments; a) being a Senator (for that see

below), Domitian should have been represented with the calcei patricii, the togate youth is only shod with the simple calcei that were appropriate for

an eques; b) the facial traits of

the togate youth are not those of a portrait; c) if the togate youth

were a portrait of Domitian, it should have been destroyed after Domitian's

assassination and damnatio memoriae.

To illustrate

point a), the `wrong´ shoes, Domitian is wearing on Frieze B, I

anticipate here a text passage, written for Chapter I.2. The consequences of Domitian's assassination ...; Introduction; at Section XI.

`Elsewhere in this volume have been discussed the problems, caused

by the fact that some of the 34 figures, that appear on the Cancelleria Reliefs

(cf. here Figs. 1; 2), are

represented as wearing the `wrong´ shoes.

Cf. infra,

at Chapter: I.1. The discussion of the Cancelleria Reliefs, or the story of a dilemma:

wrong shoes or wrong interpretations?

In that case, it took me a full year to analyse the discussion

concerning those `wrong´ shoes. Only to find out (cf. infra, in Chapter I.1.,

at n. 144), as also

suggested by Stephanie Langer and Michael Pfanner (2018, 76-77 with n. 123,

quoted verbatim infra, in Chapter I.1., at n. 193), that all the resulting problems can be explained by assuming

the simple facts that the artists had made mistakes. Langer and Pfanner (op.cit.) discuss the representation of

the Genius Senatus on Frieze B of the

Cancelleria Reliefs (cf. here Fig. 2;

and Figs. 1 and 2 drawing: figure 11),

who is clad in the simple calcei (as

appropriate for equites), instead of

wearing the calcei patricii (as

appropriate for Senators. For calcei

patricii; cf. supra, in Chapter I.1., at n. 145).

Langer and

Pfanner (2018, 66, Kapitel 2.9.3) write: "Fehler finden sich oft bei den Schuhen (A: Figuren 2, 3, 7, 8, 12,

15, 16, 17; B: Figuren 8?, 12, 14,

15, 17; s. dazu jeweils im Kapitel 2.8

unter "Technisches"): Sei

es, dass sie vergessen und nachträglich eingeritzt wurden, oder dass es

Verwechslungen mit der anschließenden Figur gab ... [my emphasis]" (`errors are often to be found concerning the

shoes´, mentioning the figures on Frieze A and B of the Cancelleria Relief

which, in their opinion, are wearing wrong shoes, inter alia figure 12 on Frieze B; `see for those figures Chapter 2.8, under: `technical observations´.

These shoes `have either been forgotten or have only been carved at a second

moment, or they have been mixed up with the shoes of the next figure´. For

a discussion; cf. infra, at ChapterV.1.d).

Figure 12 on Frieze B, mentioned by

Langer and Pfanner (2018, 66) in this context, is the togate youth, whom I

myself identify with Domitian (cf. here Figs.

1 and 2 drawing). In their discussion of this figure; cf. Langer und

Pfanner (2018, 55-56, Kapitel 2.8: "Figur 12 Junger Mann in Toga"),

where they observe that this youth is shod with the "einfachen calcei" (`simple calcei´), the authors unfortunately do

not address the fact (as we might expect after their statement on p. 66, quoted

above) in how far, in their opinion, figure

12 is wearing the `wrong´ shoes.

Ad point a). Why the togate youth on frieze B is wearing the

simple calcei,

and why he is the acting praetor urbanus and, therefore, Domitian

Personally I follow in this respect Erika Simon and Jocelyn M.C.

Toynbee, who have observed that the togate youth, whom they themselves identify

with Domitian, does not wear the

`wrong´ shoes.

Cf. Simon (1960,

134-135; ead. 1963, 10; quoted verbatim infra, ns. 175, 181, in Chapter I.1.).

Acknowledging that the head of this youth is his portrait (and explaining, why

he is wearing this kind of shoes), Simon identified this figure as Domitian,

shown in his capacity as praetor urbanus

(cf. infra), arguing that he could,

therefore, receive Vespasian in this adventus

ceremony because was the highest ranking magistrate currently present at Rome.

And I follow

Jocelyn M.C. Toynbee (1957, 7-8, quoted verbatim

infra, n. 176, in Chapter I.1.) in assuming that this togate

youth, whom she likewise identified with Domitian, is shod with the simple calcei, because he was also Princeps Iuventutis. To illustrate this

point, I anticipate in the following a passage from infra, Chapter I.1.1.:

`If at all the current magistrate praetor urbanus is portrayed in the togate youth on Frieze B, as

suggested by Erika Simon (1963, 10; cf. infra,

at n. 181), this is only

possible, as suggested by Jocelyn M.C. Toynbee (1957, 7-8), provided this praetor urbanus was Domitian in the year

70 AD. Only in his case, this magistrate, who belonged to the senatorial order,

could nevertheless have been shown as wearing the `simple calcei´, which were typical of members of the equestrian order,

because those shoes were appropriate for the Princeps Iuventutis, a title, which Domitian likewise held at that

time [with note 186: `as suggested by

J.M.C. TOYNBEE 1957, 7-8 (quoted verbatim

infra, n. 176)´]´.

Domitian held the

office praetor urbanus consulari

potestate since the 1st of January AD 70. We know also that already on 21st

December AD 69, Domitian had received the title Princeps iuventutis (for both; cf. infra, at n. 189, in Chapter I.1.). Cf. Jocelyn M.C. Toynbee (1957, 8 with n. 11, quoted verbatim infra, at n. 205, in Chapter I.1.1.), who suggested that the togate youth on

Frieze B of the Cancelleria Reliefs represents the young Domitian in his

capacity as Princeps iuventutis,

"a title that marked him out from other senators as heir presumptive to

the Empire [my emphasis]".

To Simon's (1960,

134-135; ead. 1963, 10) observation

we may add that only few Roman magistrates were allowed to welcome a newly

elected emperor in an adventus

ceremony, among them the praetor urbanus,

which means that the represented age of

the togate youth on Frieze B is decisive for the identification of this man.

The other magistrates, who could receive an emperor in an adventus ceremony, were the prafectus

urbi and the consules. The man,

who held the office praefectus urbi,

"was always a senator ... usually a senior ex-consul", as stated by

Theodore John Cadoux and R.S.O. Tomlin (1996, 1239; cf. infra, at n. 183, in Chapter I.1.), who was, therefore, definitely

much older than the togate youth. In the Republic the same had been true for

the consules, but not for Domitian !

For a detailed discussion of this subject; cf. infra, in Chapter V.1.h.1.).

I, therefore, anticipate here a text passage from this Chapter:

`The just

mentioned Republican "age limits" for all offices, inter alia that of the consules, "were often disregarded

as imperial relatives and protégés were signalled by the bestowal upon them of

the consulship"; cf. Peter Sidney Derow (1996, 384) ... With his

above-quoted remark that the traditional age limit for the consulship was

disregarded in the Imperial period, Derow was certainly right, as also the age

shows, at which Titus (at 30?) and Domitian (at 19) first became consul ... his

[i.e., Vespasian's] son Domitian

(born 24th October 51 AD) became "cos. suff." for the first time in

March-June AD 71 (at the age of 19); cf. Kienast, Eck and Heil (2017, 109,

110)´.

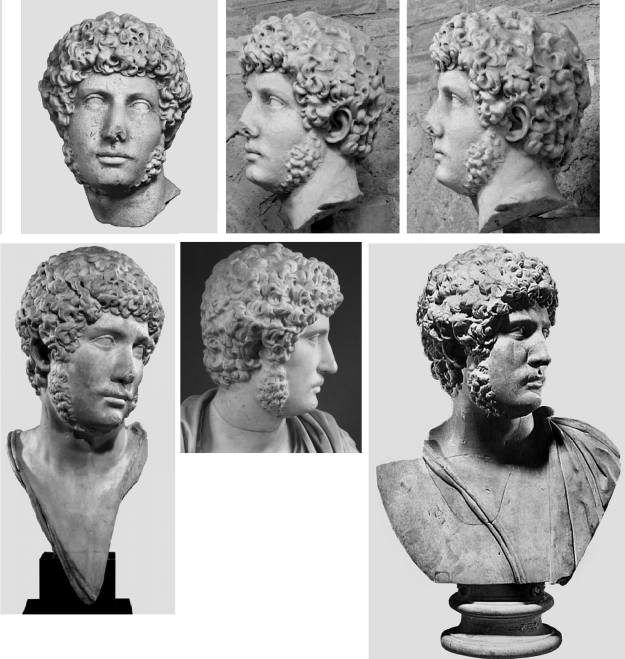

Ad points b) and c). The controversy whether the togate youth on

Frieze B is a portrait or not,

the proof that he is Domitian, and the reason, why this portrait

has not been destroyed

I myself follow in this study those scholars, who identify the

togate youth on Frieze B as Domitian, but I have also in great detail discussed

the arguments of those scholars, who deny this fact; cf. infra, in Chapters I.1.; I.1.1; V.1.i.3.; VI.3.). I see

no chance to convince those scholars `of the other Camp´ of my own opinion by

using the usual methods of scholars of `both Camps´: by describing the facial

traits of the togate youth. I have, therefore, pursued a different avenue of

research, namely by concentrating on contexts;

there are two such contexts, which are of importance here. One context is the

topography of the location at Rome, where the scene, represented on Frieze B,

is set. We know that Vespasian, coming from Brindisi, at the moment,

represented on Frieze B, has arrived at Rome on the Via Appia. The meeting place of Vespasian and Domitian, for a

variety of legal reasons, must, therefore, be the Porta Capena in the Servian city Wall. The inherent problems for

both, father and son, will be explained below.

The other context is the togate youth, seen in relation to the

figures, represented on Frieze A. Franz Xaver Schütz and I have, therefore

produced:

Figs. 1 and 2 of the Cancelleria Reliefs,

drawing,`in situ´. Visualization

created on the basis of F. Magis drawings (1945), here `Figs. 1 and 2 drawing´.

See above, at the captions of these illustrations.

We created this

visualization, because we asked ourselves, whether the assumption that the

Cancelleria Reliefs had decorated the opposite walls in the bay of an arch,

could help us to learn more about those reliefs.

Only after having

created in 2020 our own first visualization of the Cancelleria Relief `in situ´, based on the photos here Figs. 1; 2, did I have a chance to

study the similar visualization by John Henderson (2003, 249, Figs. 48; 49), which

has been mentioned by Massimo Pentiricci (2009, 61 with n. 427). For a

discussion; cf. infra, Chapter I.3.2., with n. 263. Henderson (2003, 249, Figs. 48; 49) based his visualization on

Filippo Magi's drawings (1945 = here Figs.

1 und 2 drawing), but he confronted Frieze A with Frieze B "reversed

right/left", that is to say: with a representation of Frieze B `back to

front´. Henderson has thus likewise found relationships of the figures on the

Friezes A and B. But because an ancient beholder could not possibly ever have

seen Frieze B "reversed right/left", we maintain our own method to

create this visualization. Now, in 2022, likewise on the basis of Magi's drawings.

Quite unexpectedly we thus found (first in 2020, by basing

our visualization on the photographs here Figs.

1; 2) the context of the togate youth within this pair of panels. When

these panels were in situ (cf. here Figs. 1 and 2 of the Cancelleria Reliefs,

drawing, `in situ´) the togate

youth on Frieze B (figure 12) stood

almost opposite the figure of Domitian/ Nerva in Frieze A (figure 6). Both men lead the processions, which are represented on

those friezes, and are, therefore, the main figures. Considering at the same

time that it was Domitian, who commissioned the Cancelleria Reliefs, it is

consequent to assume that the togate youth, leading the procession of the

representatives of Rome to the meeting with the homecoming new Emperor

Vespasian in an adventus ceremony,

must, therefore, be the acting praetor

urbanus, Caesar Domitian. To illustrate this point further, I anticipate

here a passage from Chapter V.1.i.3.):

`If so, Domitian [i.e.,

the togate youth] is thus only recognizable on Frieze B because of a

combination of his action - he heads the receiving party in an adventus ceremony - with the specific

topographical context, where this action is staged, the meaning of which has

just been analysed above [i.e., in

Chapter V.1.i.3.); see here below].

Although the fact

remains that the head of the togate youth, figure

12 on Frieze B (cf. here Figs. 1 and

2 drawing), has not been destroyed, which is why some scholars have

suggested that, therefore, it cannot possibly be identified as a portrait of

Domitian, which should have been destroyed after the emperor's damnatio memoriae, of course.

Whereas I myself

have developed a scenario to explain this fact (cf. infra, in Chapter II.3.1.a)

[see below], with reference to Chapter II.3.2.),

John Henderson (2003) offers a different solution to this problem, which does

not contradict my suggestion, since both hypotheses could be regarded as

complementing each other.

Henderson (2003, 246) writes:

"On Relief

`B´, we recognise the features of dear old Vespasian in the front-rank figure

to right who is being crowned by a Victory launch. And we wonder if (we can

ever decide if) the young man he is paired with has an individualised, or

blankly idealising, visage [with n. 54]: a youthful Domitian, or some worthy

public servant? A Domitian, some agree (never, in any event, a square-jaw

Titus) - a princeling Domitian re-imag(in)ed in a two decades retrospect from

the meat of his reign, and hence a Domitian unlike his former self? So Magi

reckoned, and `A´ is thus pinpointed as the start or finale of some (major?

enough to call for massive sculpture ...) campaign under Domitian's auspices,

while `B´ must B [corr.: be] a

contemporaneous resuscitation of an occasion way back in Vespasian'a era -

bringing together father and (second) son. If

Nerva displaced the head on Domitian's neck in `A´, perhaps the dead and damned

Domitian escaped defacement in `B´ precisely because he looks (so) little like

Domitian? [my emphasis].

In his note 54, Henderson writes: "His [i.e., of figure 12, the togate youth's] eyes bigger and deeper than the

lictors' [i.e., of figures 1 and 10 on Frieze B], his face more individualised than theirs, at least

(Simon [1960] 134; Bonanno [1976] 56)". - Note that Anthony Bonanno (1976,

56-57) mentions more arguments than the one, quoted by Henderson, which have

led him to identify this head of the togate youth as a portrait of Domitian´.

To conclude this point: I myself ask in this

study, whether Frieze B, when still in

situ at the Domitianic building, to which it belonged, was accessible at

all to people, who could have damaged it (cf. infra, in Chapter II.3.2.);

whereas John Henderson (2003, 246), who takes for granted that Frieze B was accessible, asks, whether the togate

youth was possibly not recognizable

as Domitian, and therefore not damaged.

Why the head of the togate youth/ Domitian on Frieze B was not

damaged

Most scholars, who discussed the Cancelleria Reliefs so far,

ignored the fact that Nerva actually had (in theory) a reason to usurp

Domitian's arch (provided, that assumption is true), for which the Cancelleria

Reliefs were created: his victory in the bellum

Suebicum. For the whole, very complex procedure; cf. infra, at Chapters II.3.1.a; II.3.2; II.3.3.a); V.1.c; V.1.i.3.).

The governor of

Pannonia, not Nerva had conducted this victorious military campaign, but

because Nerva was the reigning emperor, this victory was attributed to him. The

governor of Pannonia, therefore, sent Nerva in Rome a laurel wreath, as a sign

of his victory, which Nerva dedicated in late October or at the beginning of

November AD 97, in a solemn ceremony, to Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus;

on the same day, likewise in a solemn ceremony on the Capitoline Hill, Nerva

adopted Trajan, "whom he had previously appointed governor of Upper

Germany, as his son, co-emperor, and successor" (cf. J.B. CAMPBELL 1996,

1038-1039; cf. infra, n. 322, in Chapter II.1.e)).

Trajan was at Mogontiacum/ Mayence/ Mainz at that stage.

Cf. infra, at Chapters II.3.2.); and II.3.3.a),

and at The fourth Contribution by Peter

Herz in this volume ("Wann wurde Trajan von Nerva adoptiert?").

See also Chapter I.2. The consequences of

Domitian's assassination: Nerva is forced to adopt Trajan and Trajan creates

Domitian's negative image to consolidate his own reign ...

As a consequence of both facts (Nerva's

victory in the bellum Suebicum and

his adoption of Trajan), the Senate granted in November of AD 97 both Nerva and

Trajan for their victory in the bellum

Suebicum the title Germanicus,

which Nerva added to his official title, and which also Trajan accepted.

In my opinion, this sequence of events allows the assumption that

Nerva, when learning the news of his victory in the bellum Suebicum, gave the order to rework the portrait of Domitian

on Frieze A into a portrait of himself. As is plain to see (cf. here Fig. 1), this operation was never

finished, which allows the further assumption that Nerva must have ordered the

interruption of those works at some stage, possibly on the day, when he adopted

Trajan. I further suggest that Nerva finally ordered the destruction of the

building, to which the Cancelleria Reliefs belonged, at the latest after the

Senate, in November of AD 97, had granted him and Trajan together the

title Germanicus - for their

(alleged) victory in the bellum Suebicum,

at which neither Nerva, or Trajan had participated (!).

To further illustrate this point, I anticipate in the following a

passage, written for another Chapter

(cf. infra, at Chapter II.3.1.a) Nerva' victory in the bellum

Suebicum October AD 97):

`If indeed Nerva had wished to refer to his own victory over the Suebi in Pannonia in AD 97, when he

ordered to recut Domitian's face on Frieze A into a portrait of himself (cf.

here Fig. 1; Figs. 1 and 2 drawing,

figure 6), this idea was perhaps not so extravagant, as we might at first

glance believe. Because, provided Domitian actually had commissioned Frieze A

in order to commemorate his own victorious Sarmatian War, which the emperor had

fought in person in Pannonia in AD 92-93 against the Sarmatian Iazyges, and

likewise against the Suebi [with n. 345], as one scholar

has suggested [with n. 346], Nerva's idea

would become much better understandable (cf. infra, at Chapter II.3.2.)´.

I myself suggest

instead that Frieze A of the Cancelleria Reliefs shows Domitian's profectio to his (second) Dacian war in

the spring of AD 89 (cf. infra, at Appendix IV.d.2.e); Appendix IV.d.2.f). Further down in this Chapter, I suggest that the Cancelleria Reliefs may have decorated

the arch of Domitian, postulated by Filippo Coarelli (2009b; 2012) at the

"Porta principale" (`main entrance´) of Domitian's Palace on the

Palatine. If that is true, assuming at the same time that the Emperor Nerva

resided in Domitian's Domus Augustana

as well, it would be more than understandable that he had the intention to

appear with a portrait of himself on

Frieze A (cf. here Fig. 1, or, if

possible, on both Friezes ?), which decorated after all the arch at the

entrance of his Palace.

Cf. here Fig. 58,

labels: PALATINE; DOMUS AUGUSTANA; "Porta principale"; Arch of

Domitian ? / Cancelleria Reliefs ?

Contrary to all previous scholars, Massimo Pentiricci (2009)

suggests the following. Most of the slabs of he Cancelleria Reliefs (cf. here Figs. 1 and 2 drawing) were found in

what I call the `Second sculptor's workshop´, which Filippo Magi (1939; 1945)

excavated underneath the Palazzo della Cancelleria, next to the tomb of consul

Aulus Hirtius (cf. here Figs. 58; 59).

Together with the Cancelleria Reliefs, Magi has found there architectural

fragments, which belonged to an arch. Pentiricci believes that all those finds

belong to the same context, which means that this Domitianic building must have

been destroyed together with its pertaining Cancelleria Reliefs (cf. M.

PENTIRICCI 2009, 61 with ns. 428-431; p. 62 with ns. 440-442, p. 162 with n.

97, p. 204: "§ 3. La ristrutturazione urbanistica in età flavia (Periodo

3)"; cf. pp. 204-205: "L'officina marmoraria presso il sepolcro di

Irzio"). Cf. infra., Chapter I.3.2.), n. 297; at n. 261, in Chapter I.3.2; and at n. 334, in Chapter II.3.1.a).

For this `Second

sculptor's workshop; cf. infra, in

Chapters I.3.1.); V.1.a.1.).

Stephanie Langer

and Michael Pfanner (2018, 82), who do not discuss Massimo Pentiricci (2009) in

this context, are likewise of the opinion that the Cancelleria Reliefs were

destroyed together with the building to which they belonged. In addition to

this, they have already suggested (for different reasons than I myself) that it

could have been Nerva, who ordered the destruction of the building with the

Cancelleria Reliefs; cf. infra, in

Chapters V.1.a); V.1.b); V.1.i.1.).

In my opinion, Nerva ordered the destruction of this building

comprising the Cancelleria Reliefs because, after the above-mentioned decision

of the Senate, those Reliefs should, of course, have shown on Frieze A both Nerva and Trajan together, in their profectio ceremony for the bellum Suebicum. As is well known, the slabs of the Cancelleria

Reliefs are much too thin to allow major changes of such a kind, for example,

the carving of a second emperor next to Domitian/ Nerva on Frieze A, for

example between Minerva and Domitian/ Nerva (cf. here Fig. 1; Figs. 1 and 2 drawing: figures 5; 6); cf. infra, at Chapter II.3.2.

When trying to

find out what had actually happened to the Cancelleria Reliefs after Domitian's

assassination, we must also consider the fact that, like these panels (see for

that below), also the building itself, where those reliefs had been attached

and carved in situ (also the second

carving phase of these reliefs; see below, and infra, in Chapters II.1.d;

II.4.), was possibly not as yet

finished. To further illustrate this point, I anticipate another passage,

written for Chapter II.3.1.a):

`Nerva's victory in the bellum Suebicum October AD 97 ...

`Pfanner (1981, 516-517 with ns. 13-16, "Das Schicksal der

Reliefs", quoted verbatim infra,

n. 318, in Chapter II.1.d)) has proven, that Domitian's

face on Frieze A of the Cancelleria Reliefs [here Fig. 1; Figs. 1 and 2 drawing: figure 6] was recut into a portrait

of Nerva, when that panel was still in

situ on its Domitianic building. Domitian was murdered on 18th September AD

96. As we will learn below (cf. infra,

in Chapter II.3.2.), Nerva dedicated

at the end of October or at the beginning of November AD 97 the laurel wreath

to Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus on the Capitoline, which, as a token of

his victory over the Suebi, had been

sent to him from Pannonia - that victory, for which Nerva should receive,

together with Trajan, the title Germanicus.

When we combine these facts, it seems reasonable to assume that this Domitianic

arch, at the stage of Nerva's victory in October of AD 97, had survived

Domitian's assassination already by more that 13 months. If so, we can further

assume that this arch, following Nerva's decision, to convert this monument into

one that celebrated his own victory, had again become a building site.

Perhaps we can

even hypothesize something else: when we consider that the Cancelleria Reliefs

were not finished, when Domitian died (many parts of them have not as yet

received their final finish), the place may simply have remained, since

Domitian's death, `an abandoned building site´. - Also Giandomenico Spinola

writes in The Contribution by

Giandomenico Spinola in this volume that, in his opinion, the building, to

which the Cancelleria Reliefs belonged, had not been finished in Domitian's

lifetime.

For the fact that

many parts of the Cancelleria Reliefs had not received their final finish; cf.

also infra, ns. 135-137, in Chapter I.1;

Chapter II.1.b); n. 340 in Chapter II.3.1.a);

and Chapter V.1.i.1.).

Assuming that what was said above is true, I suggest in this study

that Domitian's portrait/ the togate youth on Frieze B (Fig. 2; Figs. 1 and 2 drawing: figure 12) survived simply because

it was not accessible to the public before the entire building, comprising the

Cancelleria Reliefs, was destroyed - at the order of Nerva, as I believe; cf. infra, at Chapter II.3.2.

And if also that

should be true, the following seems to be obvious. Only thanks to Nerva's

above-suggested decisions in AD 97, thanks to the fortunate find of the

Cancelleria Reliefs in the 1930s, which are still extant, and Filippo Magi's

exemplary publication of them (1939; 1945), we are today in the privileged

position of having the chance to study those panels.

Let's now turn to the underlying `topographical context´ of Frieze

B,

the Porta Capena in the Servian

city Wall

In my

opinion, the young Caesar Domitian is shown on Frieze B (cf. here Fig. 2; Figs. 1 and 2 drawing: figure 12)

how he, in the 1. half of October of AD 70, in an adventus ceremony, and in his capacity of praetor urbanus, receives at the boundary of the City of Rome the

newly elected Emperor Vespasian. Domitian held the office praetor urbanus consulari potestate since the 1st of January AD 70

(cf. infra, at Chapter V.1.i.3.)).

But with the subject adventus of Vespasian, as Domitian

wished his artists to represent it on Frieze B, were connected two problems:

the praetor urbanus (i.e., Domitian) could only act in this

capacity within the city of Rome, in addition to this we know that Vespasian

was negotiating at that stage with the Senate to be granted a triumph for his

victories in the Great Jewish War, from which he was just coming back (via his sojourn at Alexandria). For

Vespasian's motivation to go from Judaea

to Alexandria and for his actions there; cf. infra, at Chapter The

visualization of the results of this book on Domitian on our maps; and at Appendix II.a).

Vespasian's wish to celebrate a

triumph, in its turn, meant (in theory), that he was not allowed to transgress

the pomerium of Rome, the City's

sacred boundary, unless the Senate had granted him this triumph. We also know

that the Senate should only grant Vespasian (Titus, and Domitian !) the privilege of celebrating this triumph on the very

morning of their triumphal procession, in June of AD 71 (!).

In this specific case, the Senate

granted all three of them - Vespasian and Titus for their victories in the

Great Jewish War - and Domitian for his contemporary actions at Rome (and/ or for

his military `adventure´ in Gaul and Germany in AD 70 ?) - three separate

triumphs (so Josephus, BJ 7,5,3),

which they decided to celebrate together: this happened in June of 71 AD. Cf. infra, at Chapter III., with n. 458, providing references; Chapters V.1.i.3.); V.1.i.3.a); and at Appendix

I.c). - For Domitian's military `adventure´ in Gaul and Germany in AD 70;

cf. infra, at Chapters I.1.; I.2, ns. 229; 230, n. 458 in Chapter III., Chapter V.1.i.c.3.)

and Appendix I.c).

After

what was said above, the scene, represented on Frieze B was, therefore, in my

opinion, on purpose set at the sacred boundary of Rome, the pomerium. The Genius Populi Romani (cf. Fig.

2; Figs. 1 and 2 drawing: figure 13), who has come with Domitian (to the Porta Capena in the Servian city Wall)

to receive Vespasian in this adventus

ceremony, and who, on this relief, appears not by chance between father and son, therefore, sets his left foot on a cippus, which must mark the pomerium line. By positioning this pomerium cippus within the composition

of this relief right there, the artist has divided the areas domi (on the left hand side of the

relief) and militiae (on the right

hand side of the relief) from each other, and that for the following reasons.

Domitian in his capacity as praetor urbanus, and, on principle, the Genius Populi Romani, and likewise the

city goddess Dea Roma, were not

allowed to leave the City of Rome (i.e.,

the area domi), where all three of

them, therefore, appear on Frieze B (cf. here Fig. 2; Figs. 1 and 2 drawing: figures 2; 12; 13). Outside the City

of Rome (i.e., within the area militiae) we see on Frieze B, on the

other hand, the homecoming victorious general Vespasian (cf. here Fig. 2; Figs. 1 and 2 drawing: figure 14),

who is currently not as yet allowed to leave this area (i.e., by entering the City of Rome, that is to say, the area domi). And because we know that

Vespasian had approached the City of Rome by coming down the Via Appia, father and son are obviously

meant to meet on Frieze B of the Cancelleria Reliefs at the Porta Capena within the Servian city

Wall (cf. here Fig. 58), although

the gate itself is not represented. For a discussion of all aspects of the

Cancelleria Reliefs; cf infra, in

Chapters I.-VI.; and at The Contribution by Giandomenco Spinola

in this volume.

I myself follow Giandomenico Spinola's overall

interpretation of Frieze B of the Cancelleria Reliefs, and, therefore

anticipate here a passage, written for Chapter III. (for the following see also The Contribution by Giandomenico Spinola in this volume):

`Spinola's

new addition to all this previous knowledge consists in the following

observation. He has alerted me to the possible meaning of the gesture, which,

on Frieze B, Vespasian makes with his right hand. The emperor lifts it and lays

it on the left shoulder of the togate youth standing in front of him [in

reality, Vespasian does not touch the youth's shoulder, but from a distance it

looks like that] ... Since Spinola takes it for granted that Frieze B shows the

original portrait of that emperor and, therefore, Vespasian and Domitian, he

believes that Vespasian's gesture means that he thus bestows the (future) reign

of the Empire on his younger son Domitian. Which, if true, would mean that

Frieze B shows not only the very moment of the investiture of the Emperor Vespasian himself - as has already

earlier been observed by many scholars - but at the same time the (future) investiture, or the

"legittimazione" (so Spinola) of Domitian [my

emphasis]´.

And

because I follow Giandomenico Spinola's just-quoted interpretation of Frieze B

of the Cancelleria Reliefs, I suggest in this study, for which building

Domitian may have commissioned the Cancelleria Reliefs.

For the reasons, discussed in the following points 1.) - 5.), I believe that the Cancelleria Reliefs may have decorated one

of Domitian's two arches on the Palatine.

1.) because of the date (`late Domitianic´),

suggested for the Cancelleria Reliefs and/ or because scholars suggest that the

workshop of the Cancelleria Reliefs was also active in Domitian's Palace on the

Palatine, and in Domitian's Forum/ Forum Nervae/ Forum Transitorium (in the following called: `Domitian's Forum´).

Domitian's

Palace on the Palatine was erected between AD 81 until around 92; cf. John

Pollini (2017b, 120); and Françoise Villedieu (2009, 246), discussed infra, at Chapter V.1.i.3.b);

Section III.

Hans Wiegartz (1996, 172, quoted verbatim infra, at Appendix IV.d.2.a)) was of the opinion that the sculptural

decoration of Domitian's Forum and

the Cancelleria Reliefs were contemporary.

Giandomenico Spinola was kind enough

to tell me that, in his opinion, the Cancelleria Reliefs (cf. here Figs. 1; 2) are datable to the late

Domitianic period (cf. infra, at n. 75,

in Chapter I.1., see also The Contribution by Giandomenico Spinola

in this volume).

Pierre Gros (2009, 106-107, quoting

P. GROS 2004) suggests that Domitian's architect Rabirius, who built his Palace

on the Palatine, created at the same time Domitian's Forum; cf. infra, at Appendix IV.d.2.a); Appendix IV.d.2.f). Gros (2009, 106-107) reports also that, as a

result of the recent excavations at Domitian's Forum, quoting for that Eugenio La Rocca (1998a, 1-12), "Le

ricerche recenti hanno messo in evidenza tre fasi diverse di un cantiere che,

cominciato nell'84, durò più di un decennio ...", quoted in more detail

and discussed infra, at Appendix IV.d.2.a).

Klaus Stefan Freyberger (2018, 97;

cf. infra, at Chapter V.3.) observes that the architectural

fragments, found together with the Cancelleria Reliefs (here Figs. 1; 2), were carved by a late

Domitianic workshop that was also active in Domitian's Domus Augustana. In addition to this, Freyberger (2018, 97)

compares on stylistical grounds the architrave block, carrying the inscription

PP FECIT (CIL

VI, 40543), that was found together with the Cancelleria Reliefs, with Le Colonnacce at Domitian's Forum (cf. here Fig. 49). To this I will come back below.

For a discussion; cf. infra, at Chapter VI.3. Summary of my own hypotheses concerning the Cancelleria Reliefs

presented in this study; Addition: My

own tentative suggestion, to which monument or building the Cancelleria Reliefs

may have belonged, and a discussion of their possible date.

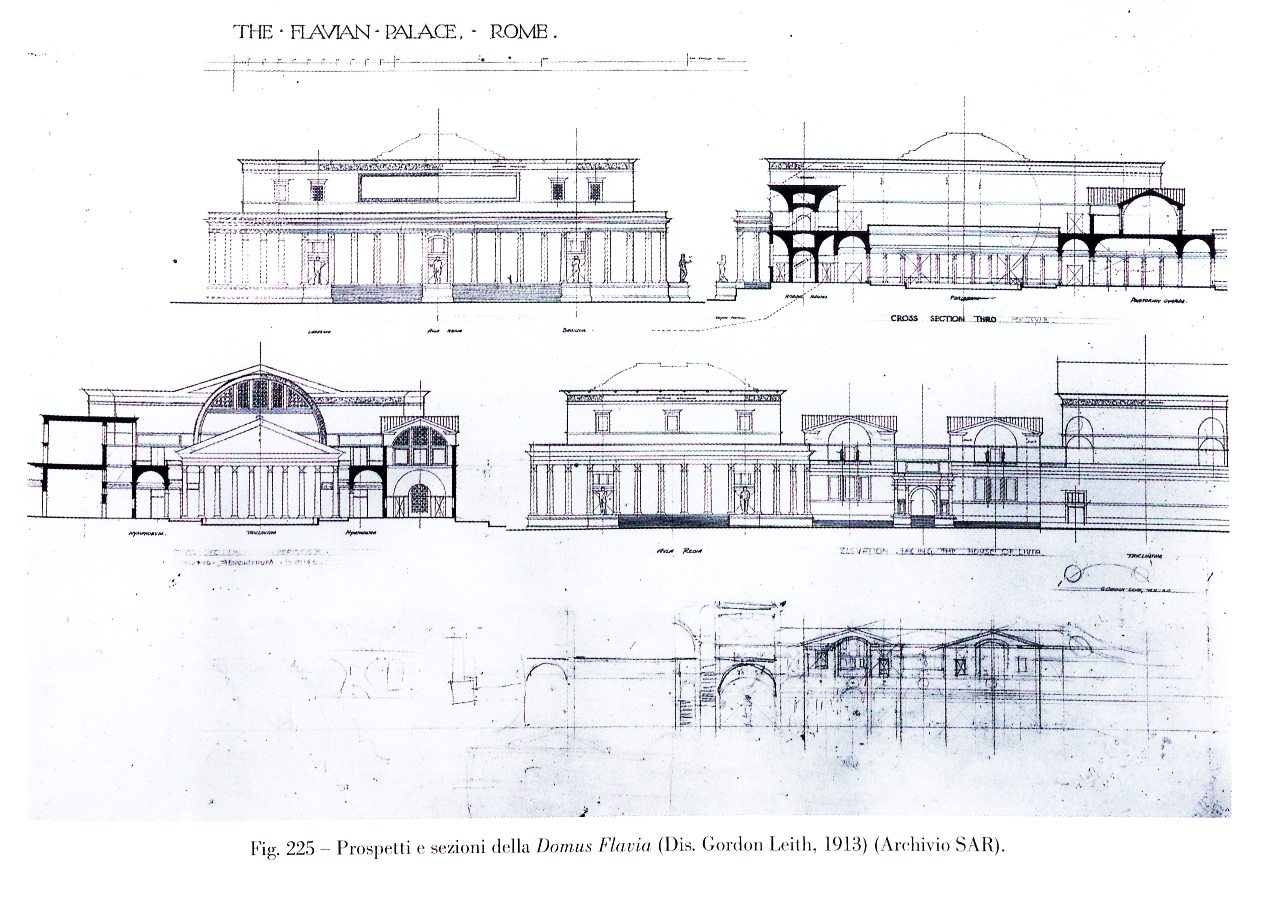

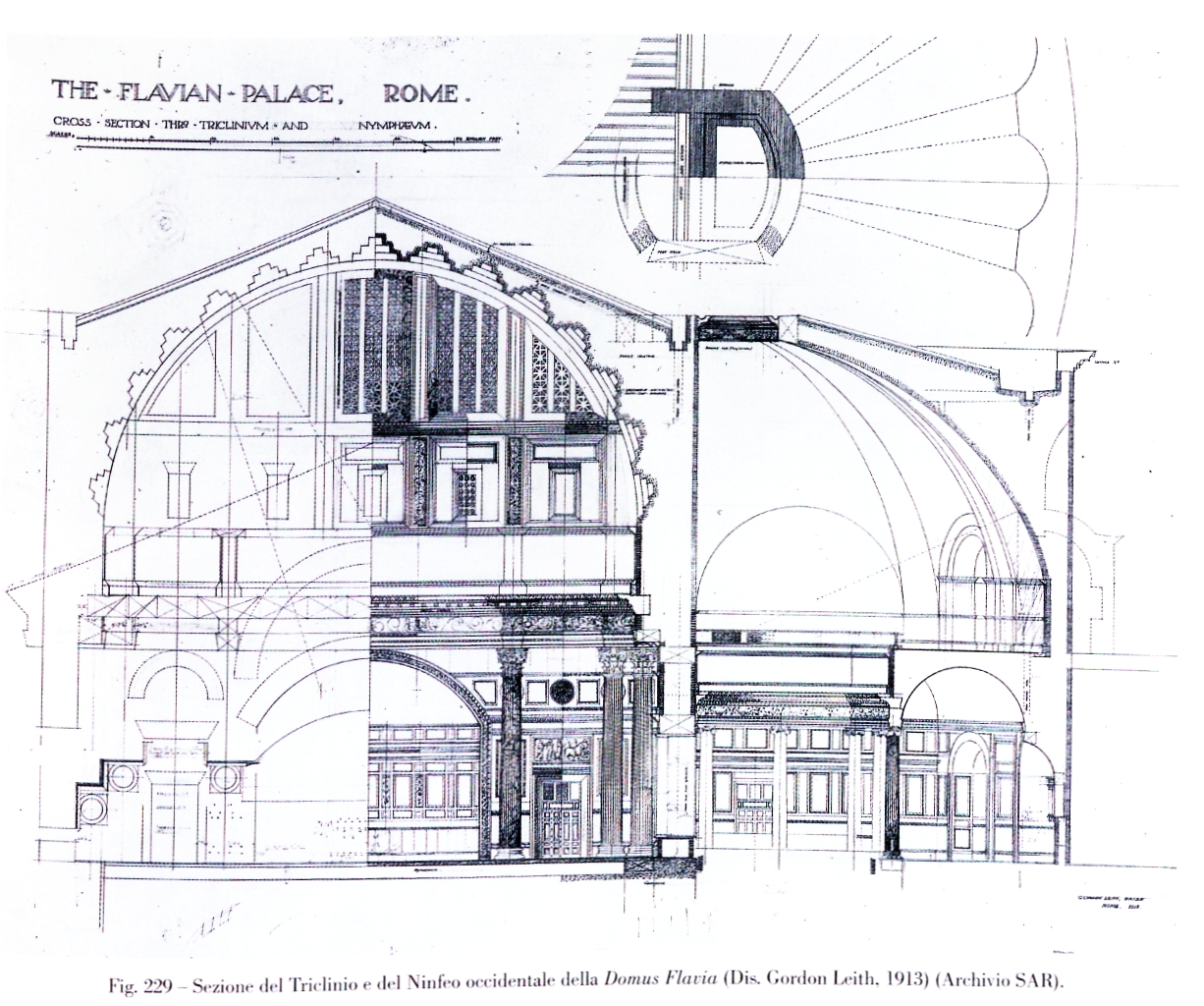

For Domitian's Palace on the

Palatine most recently; cf. the last, posthumous publication (of 2020) on this

subject by the late Ulrike Wulf-Rheidt (21st December

1963 - 13th June 2018). See also Aurora Raimondi Cominesi and Claire

Stocks (2021); Natascha Sojc (2021); and Aurora Raimondi Cominesi (2022). My

thanks are due to Hans Rupprecht Goette for sending me the article by

Wulf-Rheidt (2020).

2.) The representation of the Piroustae (here Fig. 49) in Domitian's Forum provides the date of the creation of the Cancelleria Reliefs (i.e., post AD 89).

The

representation of the Piroustae in

Domitian's Forum (here Fig. 49) helps:

a)

to date the sculptural decoration of this Forum

itself; and -

b)

because the same workshop created also the Cancelleria Reliefs (cf. supra, at point 1.)), it allows the

hypothesis, that Domitian (now Nerva) on Frieze A of the Cancelleria Reliefs

(here Fig. 1) is leaving in the

Spring of AD 89 for his (second) Dacian War,

which was victorious and that Domitian celebrated in December of AD 89 with a

triumph at Rome `over the Chatti and the Dacians´. - If true, this fact may be

regarded as a terminus post quem for

the realization of the Cancelleria Reliefs.

Cf. infra, at Appendix IV.d.2.f)

Domitian's choice to represent the Piroustae (cf. here Fig. 49) in his

Forum/ Forum Nervae/ Forum Transitorium and the date of the Cancelleria Reliefs.

For Domitian's war of AD 89; cf.

Peter L. Viscusi (1973, 58-60), quoted verbatim

and discussed infra, at Preamble: Domitian's negative image;

Section I. `The intentional creation of

Domitian's negative image´, here presented by discussing relevant text passages

from Markus Handy ("Strategien zur Legitimierung der Ermordung des

Domitian", 2015) and from Peter L. Viscusi (Studies on Domitian, 1973).

---

---

Fig. 49. Rome, Domitian's Forum/ Forum Nervae/ Forum Transitorium, detail from the only

extant part of the colonnade on the south-east side of the Forum, called Le Colonnacce.

Photo: Courtesy F.X. Schütz (March 2006).

Marble relief of a female figure in the attic storey of Le Colonnacce, previously identified as

Minerva but, as H. Wiegartz (1996) realized, actually depicting a

representation of a people; as he observed originally 42 such representations

of gentes had decorated this Forum. This figure represents the Piroustae, who, as Wiegartz observed, is

also represented in the Sebasteion at

Aphrodisias, where this representation is labelled as `Piroustoi´ (here Fig. 50). Photo: Courtesy H.R. Goette (May 2012).

The Piroustae were an Illyrian tribe (also called a

Dalmatian tribe and a Pannonian tribe), who lived in that part of the Roman

province of Illyricum, which, after the division of this province (which

probably occurred in AD 9), became the Roman province of Dalmatia.

Fig. 50. Aphrodisias, Sebasteion,

Iulo-Claudian period. Marble relief depicting a representation of the same

people as illustrated at Le Colonnacce,

called in the pertaining inscription `Piroustoi´.

Photo: Courtesy Aphrodisias Excavations (G. Petruccioli).

My

thanks are due to Amanda Claridge, Hans Rupprecht Goette, Peter Herz, Eugenio

La Rocca, Stefan Pfeiffer, Franz Xaver Schütz, Rose Mary Sheldon, and Bert

Smith, whose combined efforts - during the pandemic, when all the libraries

were closed - have helped me to understand this very complex subject.

The enquiry began when I read a

remark by the military historian Rose Mary Sheldon (2007, 199) on the effect

his suppression of the Bar Kokhba Revolt may have had on Hadrian himself. Pursuing this question further

had for me the unforeseen result that I have added to this book a detailed

study on Domitian's building projects at Rome.

Cf. infra, at Appendix IV.c.2.);

and Appendix IV.d) The summary of the

research presented in Appendix IV. has led to a summary of Domitian's building

projects at Rome. - To this I will come back below.

The reason being that I began to

study the representations of `peoples´, wich decorated the porticos of the Hadrianeum (here Fig. 48), interpreted by Marina Sapelli (1999)

as `provinciae fideles´,

ending up with Domitian's Forum.

Reading Amanda Claridge's Rome guide (2010, 174-175), I

came across an important finding, for which she herself did not provide a

reference : at Le Colonnacce in

Domitian's Forum "On the attic

storey the surviving sculptured panel in the recess shows a helmeted [page

175] female carrying a shield, recently

recognized (thanks to a labelled version found at Aphrodisias in Turkey) as the

personification of the Piroustae, a

people of the Danube".

When

asking Amanda for advice, she thought to have found this hypothesis in a

publication by R.R.R. Smith, sending me, on her own account, Bert Smith's

article ("Simulacra Gentium: The

Ethne from the Sebasteion at Aphrodisias", 1988), but in which, as Amanda

herself knew, the Piroustae are not mentioned.

Also Stefan Pfeiffer (2009, 61-62)

mentions the Piroustae (here Fig. 49) in his book on the Flavians,

but quotes Hans Wiegartz for this identification, likewise without providing a

reference. Unfortunately I could not ask any more Hans Wiegartz (23rd January

1936 - 27th March 2008) himself for advice, since he has passed away a long

time before.

These figures of representations of `peoples´ in

Domitian's Forum (cf. here Fig. 49),

of which according to H. Wiegartz (1996) originally 42 had decorated this Forum, symbolized, according to Stefan

Pfeiffer (2009, 61-62), `Domitian's

"Sieghaftigkeit", which in its turn guaranteed Rome's wealth´. This

passage is quoted in more detail infra,

as the epigraph of Appendix IV.d.2.e).

Elsewhere, Pfeiffer (2018, 189; cf. infra,

in Chapter I.2.1.a)), by analysing

the themes of Domitian's self-presentation, explains what he means with

"Sieghaftigkeit": "1. It was a key issue for Domitian to show

his virtus militaris and his

victoriousness [with n. 85, providing a reference]". Domitian in his self-presentations

thus claimed his `invincibility´.

For a detailed discussion; cf. infra, at Appendix IV.d.2.a). - To this I will

likewise come back below.

At my

request, Stefan Pfeiffer was kind enough to write me the reference of Hans

Wiegartz ("Simulacra Gentium auf dem Forum Transitorium", 1996), but

because of all the articles of the periodical Boreas precisely that article is not

available on the Internet, Hans Ruppreht Goette was kind enough to send me this

article by Wiegartz (!). In addition to this, I may publish here with Franz Xaver

Schütz's kind consent one of his photographs of Le Colonnacce (here Fig. 49).

And because Pierre Gros (2009, 106-107) had in the meantime

returned to the older opinion that this `Piroustae

relief´ in Domitian's Forum represents

Minerva, (allegedly) following with this decision Maria Paola Del Moro (2007),

I asked also the other above-mentioned scholars for help. As I should only find

out much later, Pierre Gros (2009, 107), quoting for this opinion: "(Del

Moro 2007b [i.e., here M.P. DEL MORO

2007], pp. 178-187)", erroneously asserts that it was Del Moro (2007), who

has re-identified the `Piroustae relief´

(here Fig. 49) with Minerva.

Hans Rupprecht Goette sent me, on

his own account, his photo of the Piroustae

at Le Colonnacce in Domitian's Forum (here Fig. 49), which I may publish here with his kind consent. He sent

me also a reference concerning the Piroustoi

in the Sebasteion at Aphrodisias (cf.

here Fig. 50); cf. R.R.R. Smith

(Aphrodisias VI. The Marble reliefs from

the Julio-Claudian Sebasteion, 2013), and a photo of the Piroustoi there. I knew, of course, this

relief at the Sebasteion (here Fig. 50), but had so far not realized

that this relief and the Piroustae in

Domitian's Forum (here Fig. 49), are copies of the same

prototype (!).

Because I wanted to know, whose idea

it had been first, and because Pierre

Gros (2009, 106-107) had in the meantime re-identified the `Piroustae relief´ (here Fig. 49) as a representation of

Minerva, I asked R.R.R. Smith for advice. Bert Smith wrote me that it had been

Hans Wiegartz (1996), who identified this representation as the tribe called Piroustae/ Piroustoi, a fact, which also he himself has stated; cf. Smith

(2013, 91 n. 50). In addition, Bert explained to me in this E-mail that, for

iconographic reasons, this relief at Domitian's Forum cannot possibly represent Minerva. With Bert's kind consent,

I publish here his Email as ("The

first Conribution by R.R.R. Smith on the iconography of the representation of

the Piroustae at Le Colonnacce in Domitian's Forum/ Forum Nervae/ Forum

Transitorium"). Bert Smith sent me also, on his own account, the relevant

parts of his publication of 2013, and the photo of the Piroustoi at the Sebasteion

(here Fig. 50), which I may publish

here with his kind consent.

Cf. infra, at Appendix IV.d.2.a) Who invented this iconography of defeated and

pacified `nations´ and what does it mean? With The first Contribution by

R.R.R. Smith.

In this Chapter

are discussed the publications by R.R.R. Smith (1988 and 2013), in which he has

studied all representations of `nationes´,

beginning with those of Pompeius Magnus in his theatre at Rome, but also those

of Augustus's Porticus ad Nationes at

Rome and those that derive from the `nationes´

of Augustus's Porticus ad Nationes :

the ethne of the Sebasteion at Aphrodisias (here Fig. 50), the `provinces´ of the Hadrianeum at Rome (here Fig.

48), and the `peoples´ of Domitian's Forum

(here Fig. 49). According to R.R.R.

Smith (2013, 119), Domitian's Forum