Chapter: The visualization of the results of this book on Domitian on our maps

(`Die Visualisierung der Resultate dieses Buches über Domitian auf unseren Karten´)

Änderungen auf unseren erweiterten und verbesserten Karten gegenüber den ersten Versionen von 2017:

Der

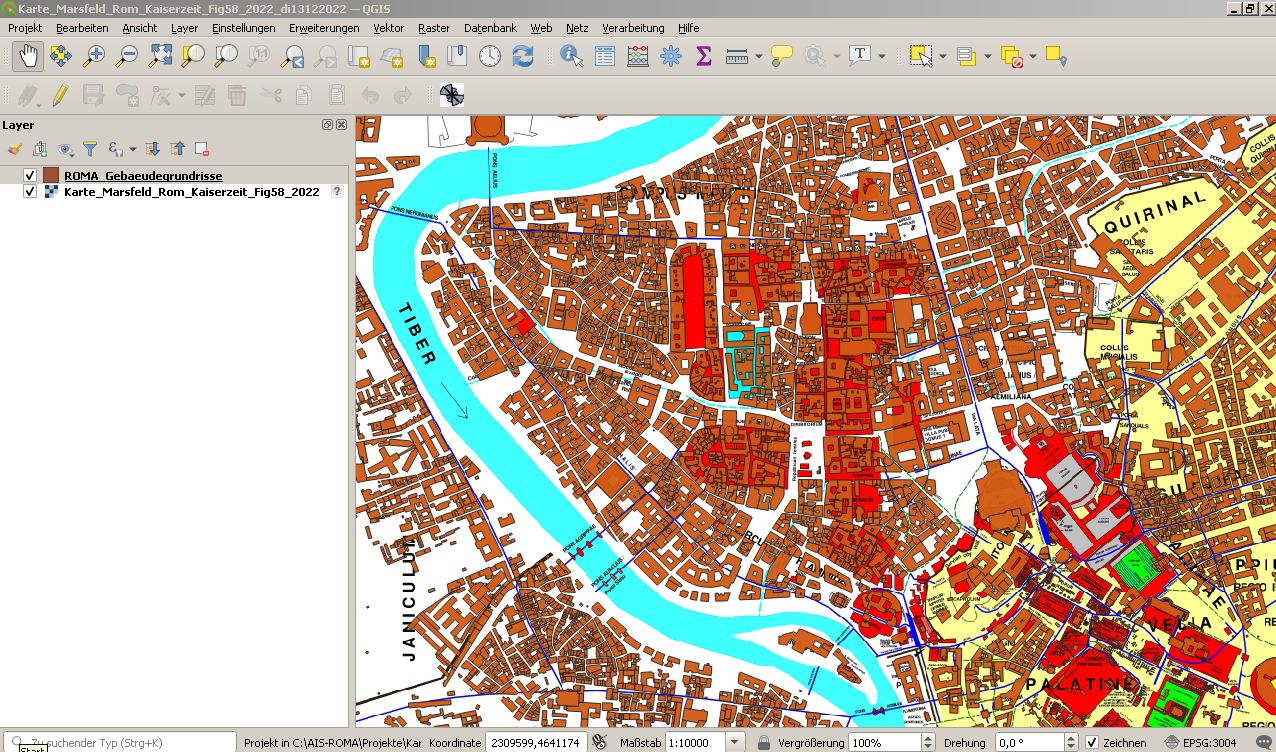

Titel unserer Karte Fig. 58 (links) lautet jetzt: "Karte des Marsfeldes

in Rom in der Kaiserzeit, mit anschließenden Stadtgebieten, 2022".

Vergleiche für die erste Version dieser Karte, die ein kleineres

Areal Roms wiedergibt, Häuber (2017, 63, Fig. 3.5).

The title of our map Fig 58 (left) is now: "Map of the Campus Martius at Rome in the Imperial period, showing also adjacent areas, 2022". For the first version of this map, comprising a smaller area: Häuber (2017, 63, Fig. 3.5).

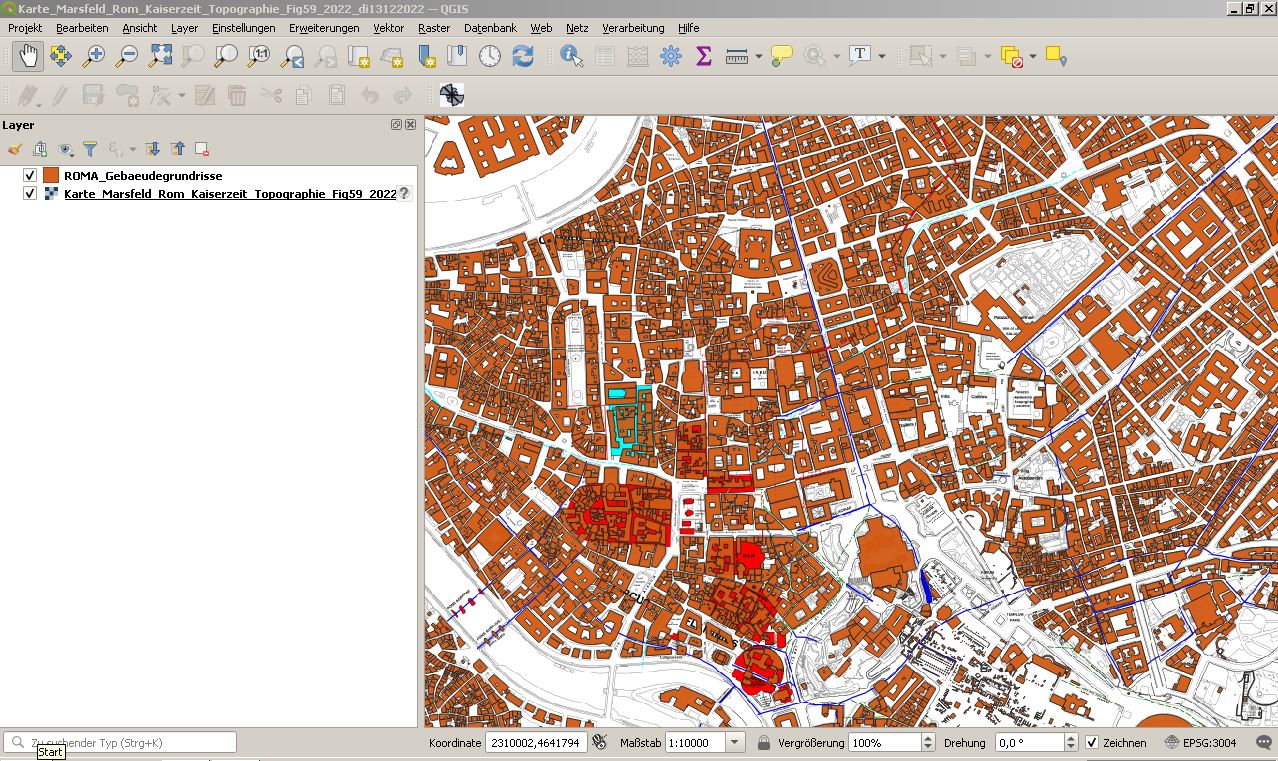

Der

Titel unserer Karte Fig. 59 (rechts) lautet jetzt: "Karte des Marsfeldes

in Rom in der Kaiserzeit, mit anschließenden Stadtgebieten, und mit

der aktuellen Topographie,

2022".

Auf dieser Karte sind die photogrammetrischen Daten sichtbar (die das

aktuelle Kataster enthalten), auf denen alle unsere Karten basieren.

Vergleiche für die erste Version dieser Karte, die ein kleineres

Areal Roms wiedergibt, Häuber (2017, 69, Fig. 3.7).

The title of our map Fig 59 (right) is now: "Map of the Campus Martius at Rome in the Imperial period, showing also adjacent areas, and comprising the current layout of the city, 2022". On this map the photogrammetric data (comprising the current cadastre), on which all our maps are based, is visible. For the first version of this map, comprising a smaller area: Häuber (2017, 69, Fig. 3.7).

Die photogrammetrischen Daten, auf denen die Karten Figs. 58; 59 basieren, wurden uns großzügigerweise vom Sovraintendente ai Beni Culturali von Roma Capitale zur Verfügung gestellt. C. Häuber, Rekonstruktionen. Diese Karten wurden mit dem "AIS ROMA" gezeichnet (C. Häuber und F.X. Schütz 2017, aktualisiert 2022).

The photogrammetric data, on which the maps Figs. 58; 59 were based, were generously provided by the Sovraintendente ai Beni Culturali of Roma Capitale. C. Häuber, reconstructions. These maps were drawn with the "AIS ROMA" (C. Häuber and F.X. Schütz 2017, updated 2022).

Die Karten Figs. 58 und 59 wurden für das Buch über Domitian (FORTVNA PAPERS III) aktualisiert, indem alle in diesem Buch erwähnten, und im kartierten Bereich der Stadt lokalisierbaren Ortsbezeichnungen (Toponyme) darauf eingezeichnet worden sind. Eine Besonderheit dieses Buches sind die Beschreibungen von `Wegen nach Rom´ und `Wegen durch die Stadt Rom´, die auf diesen Karten nachvollziehbar werden. Dabei handelt es sich in chronologischer Reihenfolge um folgende Ereignisse:

1.) Rom, Bürgerkrieg, 18.-21. Dezember 69 n. Chr.: Wege des Flavius Sabinus und des Domitian:

Am 18. Dezember 69 n. Chr. begibt sich Flavius Sabinus, praefextus urbi (Vertreter des Kaisers in der Stadt und `Polizeichef´) und älterer Bruder Vespasians, zusammen mit seinen Leuten und Personen, die auf der Seite Vepasians stehen, von seiner Domus auf dem Quirinal aus zum Palatin, um mit Kaiser Vitellius die Modalitäten von dessen Abdankung abschließend zu verhandeln.

Als sie den Lacus Fundani (beim Fons Cati) auf dem Quirinal erreicht haben, werden Flavius Sabinus und seine Begleiter (die `Flavier´) überraschend von den Soldaten des Vitellius (den `Vitellianern´) angegriffen, flüchten sich in die befestigte Area Capitolina auf dem Capitolium (den Heiligen Bezirk des Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus) auf der südlichen Kuppe des Kapitolshügels, und werden in der Nacht vom 18. auf den 19. Dezember von den Vitellianern belagert. In dieser Nacht werden auch die Söhne des Flavius Sabinus und Domitian zu ihm gebracht.

Zu den Begleitern des Flavius Sabinus gehören einflußreiche Ritter und Senatoren, die amtierenden Konsuln, sowie die Offiziere der cohortes urbanae und der vigiles, die Flavius Sabinus direkt unterstellt sind; vergleiche hierzu Alexander Heinemann (2016, 191, Abb. 3), der ebenfalls die hier beschriebenen Wege diskutiert, jedoch, im Unterschied zu mir, die Auffassung vertritt, dass sich Flavius Sabinus auf die nördliche Kuppe des Kapitols, die Arx, begeben habe.

Am Morgen des 19. Dezember wird der Tempel des Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus in Brand gesteckt, die Vitellianern dringen in die befestigte Area Capitolina ein, und während die meisten Flavier getötet werden, gelingt einigen wenigen, u.a. auf Grund von Verkleidungen, die Flucht. So auch Domitian, der sich, als Isiacus oder Isispriester gekleidet, einer Prozession anschließen kann, die das Capitolium verlässt. Flavius Sabinus und seine Söhne werden gefangen genommen und dem Vitellius auf dem Palatin in der `Domus Tiberiana´ vorgeführt; später werden sie getötet. Auch Vitellius wird (am 20. oder 21. Dezember) getötet und sein Leichnam in den Tiber geworfen. Am 21. Dezember erkennt der Senat Vespasian als neuen Kaiser an; Vespasian selbst betrachtete dagegen den 1. Juli 69 n. Chr. als seinen dies imperii (siehe dazu unten, unter 2.)).

Domitian begibt sich nach seiner gelungener Flucht vom Capitolium entweder zu einem Freigelassenen seines Vaters ins Stadtviertel Velabrum, oder zur Mutter eines Schulkameraden nach Trastevere (Transtiberim); die ihn vor den Vitellianern verstecken. Nach der Eroberung Roms durch die flavischen Truppen unter M. Antonius Primus am 20. Dezember, kommt Domitian am 21. Dezember aus seinem Versteck, wird auf Veranlassung des Gaius Licinius Mucianus als Caesar und Princeps iuventutis anerkannt und feierlich von den flavischen Soldaten zur Domus seines Vaters Vespasian auf dem Quirinal geleitet. Dort war Domitian geboren worden; er selbst sollte später an dieser Stelle das Templum Gentis Flaviae errichten, in dem er seinen Vater, Divus Vespasianus, und seinen Bruder, Divus Titus, beigesetzt hat. - Soweit meine eigene Interpretation dieses gesamten Geschehens, das kontrovers diskutiert wird. Für eine ausführliche Diskussion aller Forschungsmeinungen zu diesen Vorgängen; s.o., Kapitel The major results of this book on Domitian (`Die wichtigsten Ergebnisse dieses Buches über Domitian´); und s.u., Kapitel IV.; Kapitel V.1.i.3.); Appendix I. und Appendix IV.; sowie die folgende Vorschau

2.). Rom, 1. Hälfte Oktober 70 n. Chr. : Ankunft Kaiser Vespasians auf der Via Appia an der Porta Capena:

Der Tod Kaiser Neros (Sommer 68 n. Chr) hatte zur unmittelbaren Folge gehabt, dass Vespasian sein Oberkommando im Jüdischen Krieg niederlegte; vergleiche Rose Mary Sheldon (2007, 141; wörtlich zitiert, s.u., Anm. 412, im Kapitel III.).

Dieser Krieg hatte im Sommer 66 begonnen, als im Tempel von Jerusalem die Opfer für Roma und den römischen Kaiser untersagt, und die römische Besatzung in der Stadt ermordet worden waren; vergleiche Sheldon (2007, 134); Eck (2022, Sp. 494-495). Für den Kult der Göttin Roma und den Kaiser in den östlichen römischen Provinzen; vergleiche Stefan Pfeiffer (2010b, 23, 24; wörtlich zitiert in: C. HÄUBER 2017, 341, Anm. 94).

Cestius Gallus, der Stadthalter von Syrien, war daraufhin mit seinen Soldaten angerückt, hatte bei der Rückkehr jedoch erhebliche Einbußen erlitten, da alle Soldaten der XII. Legion getötet wurden. Als Kaiser Nero davon erfuhr, entschloss er sich, keine diplomatische Lösung dieses Konflikts anzustreben, sondern sandte im Jahre 67 Vespasian als Legat nach Judaea, mit einem Heer von 60.000 Mann; Vespasians älterer Sohn Titus kam aus Ägypten mit einer weiteren Legion hinzu (!); vergleiche für das Ganze sehr detailliert Sheldon (2007, 133-139; s.u., im Kapitel V.1.i.3.)). Bis zum Sommer 68 hatte Vespasian bereits wunschgemäß Iudaea größtenteils unterworfen; vergleiche hierzu Eck (2022, 495); Sheldon (2007, 141).

Nach Neros Tod folgte der Bürgerkrieg (68-69), das sogenannte `Vierkaiserjahr´. Erst als sich in diesem Bürgerkrieg, zu Ende des Jahres 69, die flavische Partei durchgesetzt hatte, wurden die Kampfhandlungen im Jüdischen Krieg wieder aufgenommen. Titus sollte dann im Jahre 70 Jerusalem erobern und den Tempel zerstören; vergleiche Eck (2022, Sp. 495); sowie sehr detailliert Sheldon (2007, 141-146).

Zurück zu Vespasian. Im Sommer des Jahres 69 begab sich Vespasian - ohne seine Soldaten - von Judaea nach Alexandria, um dort die Getreideflotten, die demnächst nach Rom aufbrechen sollten, aufzuhalten und auf diese Weise Rom unter Druck setzen. zu können; vergleiche Trevor Luke (2018, 195; wörtlich zitiert, s.u., Kapitel II.3.1.c)).

Und um selbst Kaiser zu werden, entschloss sich Vespasian, wie Emmanuelle Rosso (2007, 127) treffend formuliert hat, für "l'investiture égyptienne" in Alexandria, das heißt, für `die ägyptische Investitur´ (die Einsetzung als neuer ägyptischer Pharao). Vespasian habe im Übrigen gar keine andere Wahl gehabt, stellt Rosso (2007, 127) fest, da er der erste römische Kaiser gewesen sei, der nicht mt einem divus verwandt gewesen ist: "Vespasien était précisément le premier empereur de l'histoire du principat à n'avoir aucun lien de parenté avec un diuus".

Als Abschluss der Zeremonien, die Vespasian als dem neuen Pharao galten, ließ ihn dann der praefectus aegypti, Ti. Iulius Alexander, ein Freund seines Sohnes Titus von den in Alexandria stationierten Legionen am 1. Juli 69 n. Chr. als Imperator (Kaiser) akklamieren; vergleiche Häuber (2014a, 152-153). Das war der bereits oben erwähnte dies imperii Vespasians. Für alle diese hochkomplexen Vorgänge und deren Bedeutung; s.u. Appendix II.a).

Nachdem Ende des Jahres 69 die Kampfhandlungen im Jüdischen Krieg wieder aufgenommen worden waren, und Vespasian das Oberkommando seinem älteren Sohn Titus übertragen hatte (vergleiche W. ECK 2022, Sp. 495; R.M. SHELDON 2007, 141), kehrte Vespasian nach Italien zurück.

In Brindisi angekommen, legte Vespasian seine militärische Kleidung ab, und zivile Kleidung an und machte sich auf den 500 km langen Weg nach Rom, wo er in der 1. Hälfte Oktober 70 n. Chr. eintraf; s.u., Anm. 195, in Kapitel I.1.1. Da Vespasian von Brindisi kam, muss er Rom, auf der Via Appia reisend, an der Porta Capena innerhalb der Servianischen Stadtmauer erreicht haben (vergleiche hier Fig. 58).

Meines Erachtens ist dieser adventus Vespasians in der 1. Hälfte des Oktober 70 n. Chr. auf Fries B der Cancelleria Reliefs dargestellt (hier Fig. 2; Figs. 1 und 2 Zeichnung: Figuren 14 [Vespasian] und 12 [Domitian]): Vespasian wird auf diesem Relief von den Repräsentanten der Stadt Rom empfangen (von links nach rechts), der Stadtgöttin Dea Roma, fünf Vestalinnen, dem Genius des Senats und dem Genius des Römischen Volkes, sowie dem amtierenden praetor urbanus, seinem jüngeren Sohn und Caesar, Domitian; Domitian hatte seit dem 1. Januar 70 die Magistratur praetor urbanus consulari potestate inne.

Vergleiche hierzu das Kapitel The major results of this book on Domitian (`Die wichtigsten Ergebnisse dieses Buches über Domitian´); sowie Kapitel I.2. Die Folgen von Domitians Ermordung ...; Einführung; Abschnitt I; und Kapitel V.1.i.3.).

3.) Rom, Juni 71 n. Chr.: Der Weg vom Iseum Campense zur Porticus Octaviae, den Vespasian und Titus (und Domitian ?) am Morgen ihres gemeinsamen Triumphzugs gegangen sind:

Titus war erst kurz vor ihrem Triumph im Juni 71, zusammen mit seinem siegreichen Heer, aus dem Großen Jüdischen Krieg nach Rom zurückgekehrt. Vespasian und Titus verbrachten dann zusammen mit ihren Soldaten die Nacht vor dem gemeinsamen Triumphzug auf dem Marsfeld, in der Nähe des ägyptischen Heiligtums Iseum Campense und der Villa Publica. Am folgenden Morgen (das heißt, vor dem Beginn ihres Triumphzugs) begaben sich Vespasian und Titus (und Domitian ?) zur Porticus Octaviae am Circus Flaminius, wo sie sich mit Vertretern des Senats trafen, die ihnen (erst zu diesem späten Zeitpunkt !) offiziell mitteilten, dass der Senat dem Vespasian und dem Titus für ihre Siege im Großen Jüdischen Krieg Triumphe zugestanden habe, sowie dem Domitian einen eigenen Triumph für seine gleichzeitigen Aktivitäten in Rom. Dieses Treffen fand in der Porticus Octaviae statt, weil sich dieses Gebäude außerhalb der heiligen Stadtgrenze Roms, dem pomerium, befand. Nota bene: Wir wissen von Flavius Josephus (Bellum Judaicum 7,5,3), der diesen Text im Auftrag von Vespasian und Titus verfasst hat (s.u., Anm. 201, in Kapitel I.1.1.), dass der Senat bei dieser Gelegenheit allen drei Männern: Vespasian, Titus und Domitian, je einen separaten Triumph zugestanden hatte; sie beschlossen allerdings, gemeinsam einen Triumph zu feiern.

Der hier beschriebene Weg von Vespasian, Titus (und Domitian) ist bislang in der Forschung noch nicht diskutiert worden, Ich habe mich bereits 2017 mit ihm beschäftigt und eine mögliche Route vorgeschlagen, nachdem Franz Xaver Schütz und ich den entsprechenden Teil des Stadtgrundrisses rekonstruiert hatten; s.u., im Kapitel I.2. Die Folgen von Domitians Ermordung ...; Einführung; Abschnitt I., wo ich diese Forschungen fortgesetzt habe.

4.) Rom, Juni 71 n. Chr.: Der Weg, des Triumphzugs von Vespasian, Titus und Domitian:

Hierzu gibt es sehr verschiedene Vorschläge, die ich bereits 2017 und erneut in diesem Buch im Detail diskutiert habe. Mit dieser Thematik hängen zwei weitere, ebenfalls umstrittene Fragestellungen zusammen: Welchen Verlauf hatte das Pomerium zum fraglichen Zeitpunkt, und welches Tor haben Vespasian, Titus und Domitian als ihre Porta Triumphalis gewählt? Auch für die ausführliche Diskussionen dieser Themen; s.u., Kapitel I.2.; Einführung; Abschnitt I.

5.) Rom: Unter der Herrschaft Domitians: Der Weg vom Forum zu Domitian's Palast auf dem Palatin:

Sobald Domitian seinen Palast auf dem Palatin, die Domus Augustana, vollendet hatte (Bauzeit circa 81-92 n. Chr.), schuf er einen repräsentativen Aufgang dorthin, indem er die Straße Vicus Apollinis ?/ `Clivus Palatinus´ anlegen liess. Diese Straße führte vom Titusbogen (das heisst, dem Bogen des Divus Titus) auf der Velia, der sich in der Nähe des Forum Romanum befindet, hinauf auf den Palatin zu seinem Palast.

Filippo Coarelli (2009b, 88; ders. 2012, 481-483, 486-491) hat diesen Weg und seine Bedeutung für Domitian beschrieben. Der `Arcus Domitiani´ (`Domitianischer Bogen´), der vor der Fassade seines Palastes stand und den `Clivus Palatinus´ überspannte, und von dem noch Reste eines der Pylone (die aus späterer Zeit stammen) sichtbar sind, kann nach Coarellis Ansicht von Domitian seinem Vater, dem Divus Vespasianus, geweiht worden sein. Der Clivus führte dann, so Coarelli, nach einer Linkskurve zum Haupteingang des Palastes, wo Coarelli einen dritten Bogen, und zwar für Domitian, annimmt, den er mit dem aus den Constantinischen Regionenkatalogen bekannten Pentapylon identifiziert, und den er sich als einen Triumphbogen vorstellt.

Die Motivation Domitians, den Weg zu seinem Palast mit Hilfe dieser Bögen für den Divus Titus und für den Divus Vespasianus `sakral zu überhöhen´, wie Coarelli (2012, 483) sich ausdrückt, hat er sehr treffend formuliert:

"La scelta di `sacralizzare´ questo percorso con monumenti dedicati ai due primi imperatori flavi si spiega con l'assoluta centralità dell'elemento dinastico nella politica di Domiziano [Hervorhebung von mir]".

Der Bereich des Haupteingangs auf der Nordseite von Domitians Palast ist sehr stark zerstört, weshalb sich Coarellis Hypothese, hier einen Triumphbogen für Domitian anzunehmen, augenblicklich nicht verifizieren lässt (siehe dazu unten). Aber bereits Ulrike Wulf-Rheidt und Natascha Sojc (2009, 268-272, Figs. 3; 4), auf die sich Coarelli (2012) bei seinem Vorschlag berufen hat, und Wulf-Rheidt (2020, 188), die jedoch ihrerseits Coarellis (2012) Hypothese nicht erwähnt, lokalisieren an derselben Stelle wie Coarelli den Haupteingang der Domus Augustana, und zwar stellt sich Wulf-Rheidt (2020, 188) diesen Haupteingang zum Palast ebenfalls in Form eines Bogens vor. Des Weiteren konnte Wulf-Rheidt (2020, 188) feststellen, dass dieser Haupteingang zu Domitians Domus Augustana mit Sicherheit bereits zur Zeit Domitians existiert hat.

Ausgehend von der Beobachtung anderer Gelehrter; s.o., Kapitel The major results of this book on Domitian (`Die wichtigsten Ergebnisse dieses Buches über Domitian´), dass die Cancelleriarelefs spätdomitianisch datierbar seien und dass die Werkstatt, welche die Cancelleria Reliefs geschaffen hat, auch im Palast Domitians auf dem Palatin und auf seinem Forum/ Forum Nervae/ Forum Transitorium tätig war, schlage ich selbst in diesem Buch Folgendes vor.

Die Cancelleriareliefs (hier Figs. 1; 2; Figs. 1 und 2 Zeichnung; Figs. 1 und 2 der Cancelleriareliefs, Zeichnung, `in situ´) waren möglicherweise im Durchgang von Domitians Bogen des Divus Vespasianus auf dem Palatin angebracht. Oder vielleicht eher in einem der Durchgänge des Domitiansbogens, den Coarelli am Haupteingang der Domus Augustana lokalisiert. Und zwar wegen der Inhalte der Friese, die beide Domitian verherrlichen, andererseits wird mit der Geste Vespasians auf Fries B (Figs. 1 und 2 Zeichnung: Figuren: 14; 12), der seine rechte Hand auf die linke Schulter Domitians legt (in Wirklichkeit berührt Vespasians Hand Domitians Schulter gar nicht, aber aus der Entfernung sieht es so aus), hervorgehoben, dass Domitian die Legitimation seiner Herrschaft von seinem Vater, dem Divus Vespasianus, erhalten hat; s.o., Kapitel The major results of this book on Domitian (`Die wichtigsten Ergebnisse dieses Buches über Domitian´; sowie The Contribution by Giandomenico Spinola in diesem Band, dessen diesbezüglicher Idee ich hier folge.

Diese Tatsache passt meiner Meinung nach sehr gut zu Coarelli's (2012, 483) oben zitierter Beobachtung, `dass für die Politik Domitians der Hinweis auf seine Dynastie von zentraler Bedeutung´ gewesen sei.

Die Cancelleriareliefs sind in grobianischer Weise von dem Gebäude abgenommen worden, an dem sie ursprünglich angebracht waren, da sie jedoch im Depot einer Bildhauerwerkstatt angetroffen worden sind, sollten sie womöglich (zum Teil) wiederverwendet werden. Des Weiteren haben bereits andere Forscher vermutet, dass das Gebäude, zu dem die Cancelleriareliefs gehört hatten, zusammen mit diesen Reliefs absichtlich zerstört worden sei. Vorausgesetzt, dass es diesen von Coarelli postulierten Domitiansbogen am Haupteingang von Domitians Domus Augustana tatsächlich gegeben haben sollte, dann würde meine Hypothese, die Cancelleriareliefs an diesem Bogen anzubringen, auf Grund von Tatsachen gestützt, die Wulf-Rheidt (2020, 188) feststellen konnte. Dieser Eingangsbereich von Domitians Palast auf dem Palatin ist nämlich von den nachfolgenden Kaisern sehr stark verändert worden, was offensichtlich bedeutet, dass im Zuge dieser Veränderungen die domitianische Phase dieses Haupteingangs zerstört worden ist.

Für eine Diskussion dieses 5. Weges, den man auf unserer Karte Fig. 58 nachvollziehen kann, vom Forum zu Domitians Palast, sowie zu meiner Hypothese, dass die Cancelleriareliefs an einem dieser beiden Bögen Domitians auf dem Palatin angebracht gewesen sein könnten; s.o., Kapitel The major results of this book on Domitian (`Die wichtigsten Ergebnisse dieses Buches über Domitian´); sowie Kapitel VI.3; Addition (Zusatz); und für die Auffindung der Cancelleriareliefs in einer Bildhauerwerkstatt; s.u., Kapitel V.1.; V.1.a); V.1.a.1.).

Für die Hypothese, dass das Gebäude, zu dem die Cancelleriareliefs gehört hatten, zusammen mit den Reliefs zerstört worden sei, zitiere ich eine Textpassage aus dem Kapitel The major results of this book on Domitian (`Die wichtigsten Ergebnisse dieses Buches über Domitian´):

`Im Unterschied zu allen früheren Gelehrten, schlägt Massimo Pentiricci (2009) Folgendes vor. Die meisten Platten der Cancelleriareliefs (vergleiche hier Figs. 1 und 2 Zeichnung) stammen aus dem von mir so genannten `Second sculptor's workshop´ (der `zweiten Bildhauerwerkstatt´), die Filippo Magi (1939; 1945) unter dem Cancelleriapalast neben dem Grab des Konsuls Aulus Hirtius, ausgegraben hat. Zusammen mit den Cancelleriareliefs hat Magi dort Architekturfragmente angetroffen, die zu einem Bogen gehören. Pentiricci ist der Auffassung, dass all das ursprünglich aus demselben Kontext stammt, weshalb dieses domitianische Gebäude zusammen mit den Cancelleriareliefs abgerissen worden sein müsse (vergleiche M. PENTIRICCI 2009, 61 mit Anm. 428-431; S. 62 mit Anm. 440-442, S. 162 mit Anm. 97, S. 204: "§ 3. La ristrutturazione urbanistica in età flavia (Periodo 3)"; vergleiche S. 204-205: "L'officina marmoraria presso il sepolcro di Irzio"); s.u., Kapitel I.3.2.), Anm. 297; zu Anm. 261, in Kapitel I.3.2; und zu Anm. 334, in Kapitel II.3.1.a). Zu dieser `zweiten Bildhauerwerkstatt´; s.u., Kapitel I.3.1.); V.1.a.1.).

Stephanie Langer und Michael Pfanner (2018, 82), die Massimo Pentiricci (2009) in diesem Zusammenhang nicht zitieren, sind ebenfalls der Ansicht, dass das Gebäude, zu dem sie gehörten, zusammen mt den Cancelleriarelifs abgerissen worden sei. Des Weiteren haben sie bereits vorgeschlagen (wegen anderer Gründe als ich), dass es Nerva gewesen sein könnte, der die Zerstörung des Gebäudes mit den Cancelleriareliefs in Auftrag gab; s.u., Kapitel V.1.a); V.1.b); V.1.i.1.)´.

Die folgenden Textpassagen stammen aus dem Kapitel:

I.2. The consequences of Domitian's assassination:

Nerva is forced to adopt Trajan and Trajan creates Domitian's negative image to consolidate his own reign. With Hadrian's adoption manquée in October of AD 97, his 20-year long road to his accession and his thanksgivings for it, his Temple complex in the Campus Martius. Or :

The wider topographical context of the Arch of Hadrian alongside the Via Flaminia which led to the (later) Hadrianeum and to Hadrian's Temples of Diva Matidia (and of Diva Sabina?). With discussions of Hadrian's journey from Moesia Inferior to Mogontiacum (Mayence) in order to congratulate Trajan on his adoption by Nerva, and of Hadrian's portrait-type Delta Omikron (Δο) (cf. here Fig. 3). With The fourth and the fifth Contribution by Peter Herz, with The Contribution by Franz Xaver Schütz (cf. here Fig. 77), and with The Contribution by John Bodel;

INTRODUCTION; Section I. The motivation to write this Chapter:

W. Eck's (2019b) new interpretation of the inscription CIL VI 40518, the decision to correct my own relevant errors in my earlier study (2017), and the subjects discussed here, as told by the accompanying figures and their pertaining captions:

Der Titel dieses Kapitels lautet, ins Deutsche übersetzt:

Die Folgen von Domitians Ermordung:

Nerva wird gezwungen, Trajan zu adoptieren und Trajan gibt das negative Image von Domitian in Auftrag, um seine eigene Herrschaft zu konsolidieren. Mit Diskussionen der adoption manquée Hadrians im Oktober 97 n. Chr., von Hadrians 20 Jahre dauerndem Weg zu seinem eigenen Herrschaftsbeginn und seinem Dank dafür, der Errichtung seines Tempel Komplexes auf dem Marsfeld. Oder :

Der weitere topographische Kontext des Hadriansbogens an der Via Flaminia, der zum (späteren) Hadrianeum führte und zu Hadrians Tempel der Diva Matidia (und der Diva Sabina ?). Mit Diskussionen von Hadrians Reise von Moesia inferior nach Mogontiacum (Mainz), um Trajan zu seiner Adoption durch Nerva zu gratulieren, und zu Hadrians Portraittyp Delta Omikron (Δο) (vergleiche hier Fig. 3). Mit Dem vierten und fünften Beitrag von Peter Herz, mit Dem Beitrag von Franz Xaver Schütz (vergleiche hier Fig. 77) und mit Dem Beitrag von John Bodel;

EINFÜHRUNG; Abschnitt I. Die Motivation, dieses Kapitel zu verfassen: ... und die in diesem Kapitel behandelten Themen, die von den begleitenden Abbildungen und ihren zugehörigen Bildunterschriften erzählt werden.

"Let's begin with the, in my opinion, easiest approach to the complex subjects, discussed in this Chapter (which, in reality, is another monograph within this study on Domitian): by looking at the following illustrations and by reading the captions of those figures.

All our maps, now updated and illustrated in the following, were already published in my earlier study of 2017. They are two large maps of the Campus Martius at Rome and adjacent areas: here Fig. 58 (this map shows the ancient buildings, discussed in my earlier study of 2017 and in this new book), and the map Fig. 59 (this map shows the ancient buildings and the modern topography together). This map can, therefore, help the user to find the precise sites of those ancient buildings more easily, when walking through Rome.

The maps that are details of those two larger maps: are here Figs. 60; 61; 64, 65 and 66. All of them are characterized by different additions to the maps Figs. 58 and 59, and some of the cartographic details they contain are addressed in this Introduction ...".

"Please note the corrections on our updated maps here Figs. 58; 59; 60; 61; 62; 63; 64; 65; 66.

Our maps here Figs. 58; 59; 60; 61; 62; 63; 64; 65; 66, first published in 2017 and illustrated here again, have been updated in the meantime. I maintain my hypothesis concerning the north-south axis, drawn on Figs. 62; 64; 65; 66, but I have corrected seven cartographic details in those maps:

The seven cartographic corrections on our updated maps

1:) the structure, labelled as "Tempio di Siepe" -

on the first versions of the maps here Figs. 58; 59; 60; 62; 63; 64; 65; 66 (cf. C. HÄUBER 2017, Figs. 3.5; 3.7; 3.7.1; 5.2; 3.7.3; 3.7.5.a; 3.7.5b; 3.7.5.c), and located within the first cortile of the Collegio Capranica at Palazzo Capranica, may instead be identified with the western half of the apse of the Temple of Diva Matidia.

[In my earlier study (2017), I had also discussed an alternative hypothesis (which I now believe is true), namely that the "Tempio di Siepe" stood to the north of this first cortile of the Collegio Capranica. For a detailed discussion; cf infra in this Chapter, at Section VI.]

This I have realized thanks to two visits on site at the Palazzo Capranica on 19th April 2018 and on 27th November 2019. Previously neither the Torre Capranica, nor the first cortile within the Collegio Capranica, the Teatro Capranica with its grandiose staircase (the "Scalone". For the Torre Capranica, the Teatro and the Scalone; cf. here Figs. 62; 66), nor the basements of Palazzo Capranica were accessible to me. These visits were kindly arranged for me by the art historian Laura Gigli, Arch. Giuseppe Simonetta, Arch. Gabriella Marchetti, and Arch. Marco Setti, who also accompanied me and gave me guided tours to the palazzo and to the architectural remains in its basements.

In addition to this, I have studied the article by Simonetta and Gigli, which comprises Simonetta's reconstructed ground-plan of the Temple of Diva Matidia that is based on the architectural remains documented by them in the basements of Palazzo Capranica (cf. id. 2018 [2021], 128-129 with n. 7, pp. 164-165, Fig. 1 = here Figs. 67; 67.1).

Giuseppe Simonetta has drawn his reconstructed ground-plan of the Temple of Diva Matidia with a thin green line; cf. here Figs. 67; 67.1. On our map Fig. 58, Simonetta's ground-plan of the Temple of DIVA MATIDIA is likewise drawn with a thin green line, whereas on all our other maps (here Figs. 59-66), Simonetta's ground-plan of the Temple of Diva Matidia is drawn with a thin red line.. All this is in detail discussed below in Section VI. of this Chapter.

Consequently, the "Tempio di Siepe" did not stand within the first cortile of the Collegio Capranica, as I myself (2017) and other scholars have (erroneously) suggested. According to my current knowledge, the "Tempio di Siepe", which, according to Alò Giovannoli's etching (1616; cf. here Fig. 69.2) stood `behind Palazzo Capranica´, cannot be located precisely, which is why it does not appear on our maps any more. For a discussion; cf. infra, in Sections IX and XII. of this Introduction;

2.) Hadrian's basilicas within his Temple complex, dedicated to Diva Matidia and to Diva Marciana:

as already mentioned above, concerning the identifications of the two basilicas, dedicated by Hadrian to Diva Matidia and Diva Marciana, respectively, I believe now that they may possibly be identified with the structures immediately to the west and east of my Temple of Diva Matidia, which on my maps of 2017 are labelled as follows: "Halls belonging to the Temple of [DIVA] MATIDIA ?". Whereas now they are labelled: "Halls belonging to the Temple of DIVA MATIDIA ? or BASILICA I ?; Halls belonging to DIVA MATIDIA ? or BASILICA II ?

The reason for this change of ideas is again Simonetta's reconstructed ground-plan of the Temple of Diva Matidia (cf. G. SIMONETTA and L. GIGLI 2018 [2021], 164-165, Fig. 1 = here Figs. 67; 67.1). We have integrated Simonetta's reconstruction of his Temple of Diva Matidia into our maps here Figs. 58; 59; 60; 62; 64; 65; 66. Whereas Simonetta himself has drawn the ground-plan of his Temple of Diva Matidia with a green line, I have drawn it with a red line (the exception being our map Fig. 58, where it is likewise drawn with a green line) to show shat this is Simonetta's reconstruction of this ancient building (normally I draw the ground-plans of ancient buildings as red areas).

When we compare our resulting new ground-plan of the Palazzo Capranica (here Figs. 58; 59; 60; 62; 63; 64; 65; 66) with the representation of the Temple of Diva Matidia on Hadrian's medallion, which shows his Temple of Diva Matidia (here Fig. 68), the just-mentioned conclusion seems to be obvious.

The reason being that our new ground-plan of Palazzo Capranica has three parts, with Simonetta's reconstructed ground-plan of his Temple of Diva Matidia (here Figs. 67; 67.1) in the precise geometric centre (at the site of the Teatro Capranica on Nolli's ground-plan of Palazzo Capranica; cf. here Figs. 62; 63), flanked by two smaller areas of exactly the same sizes on either side (at the site of the Torre Capranica in the west, and at the site of the "Scalone", grand staircase, of the Teatro in the east, respectively). Exactly as the Temple of Diva Matidia, represented on Hadrian's medallion (here Fig. 68), which shows three aediculae: a larger one in the centre, with the seated cult-statue of Diva Matidia, flanked on either side by smaller aediculae of equal sizes, each with a standing female statue. And immediately adjacent to those two smaller aediculae follow on Hadrian's medallion (here Fig. 68) the two basilicas. In my reconstruction of 2017, I had instead located those two basilicas at the (presumed) site of the Church of S. Salvatore in Aquiro ?/ the `Casa Giannini´, and at the site of the Church of S. Maria in Aquiro, that is to say, to the west and to the east of Piazza Capranica (cf. here Fig. 66).

This change of ideas concerning the locations of Hadrian's two basilicas has, of course, consequences that are in detail discussed infra, in the caption of here Fig. 68. There, I have come to the following conclusion:

`If the two basilicas, dedicated by Hadrian to Diva Matidia and to Diva Marciana, stood instead at the sites of my so-called `Halls´, flanking my Temple of Diva Matidia on either side, we need to explain, what kind of ancient buildings were standing at the site of the Church of S. Salvatore in Aquiro ? and at the site of the Church of S. Maria in Aquiro´.

Besides, when comparing my new hypothesis concerning Hadrian's two basilicas with Heinz-.Jürgen Beste's and Henner von Hesberg's reconstructions of their Precinct and Temple of Diva Matidia (2015, 242, Fig. 28; Tav. II, K; cf. here Fig. 64), they have basically suggested the same arrangements of those three buildings: the Temple of Diva Matidia in the centre, flanked on either side by the two basilicas of equal size, dedicated to Diva Matidia and Diva Marciana, respectively. With the crucial difference that in Beste's and von Hesberg's reconstructions (here Fig. 64) these three buildings are located more to the south than in my own reconstruction, with their Temple of Diva Matidia standing right in the middle of Piazza Capranica, in front of Palazzo Capranica;

3.) my new reconstruction of the ground-plan of the Temple of Diva Sabina ?:

thanks to the relevant critique by Francesca Dell'Era (2020, 118 with n. 40), who has rejected (the northern part of) my reconstruction of the Temple of Diva Sabina ? in my earlier study (2017), I have now changed my reconstruction of the Temple of Diva Sabina ? accordingly. In my new reconstruction, the ground-plan of my Temple of Diva Sabina ? does not `overlap´ any more the area of the Istituto di S. Maria in Aquiro, where Fedora Filippi and Francesca Dell'Era have conducted their excavations; cf. Filippi and Dell'Era (2015, 220, Fig. 1; see also here Fig. 66). As Dell'Era (2020, 118 with n. 40) states, no finds that could be attributed to such a temple, have occurred within the area excavated by them. To my new reconstruction of the Temple of Diva Sabina ? (cf. here Fig. 66) I will come back below; cf. infra in this Introduction, at the Sections XII. and XIII.;

4.) the ground-plan of the Palazzo Capranica, drawn by Giambattista (G.B.) Nolli on his Large Rome map (1748):

In the updated versions of our maps Figs. 59; 60; 62; 63; 64; 65; 66, shown here, the ground-plan of the Palazzo Capranica is not any more drawn with red broken lines, but instead with black broken lines The reasons for this decision are explained in detail above (cf.supra, the caption of Fig. 66). This palazzo stands on the north-side of Piazza Capranica (here Fig. 62.8). In the first versions of our maps here Figs. 59; 60; 62; 63; 64; 65; 66, I had copied the ground-plan of this palazzo from Giambattista (G.B.) Nolli's Large Rome map (1748; cf. here Figs. 62; 62.1; 62.1.A; 62.2; 63). Nolli's drawing of the ground-plan of Palazzo Capranica had been the reason for me in my earlier study of 2017 to (tentatively) assume the Temple of Diva Matidia at the site of Palazzo Capranica, because of the similarity of Nolli's ground-plan of Palazzo Capranica with Hadrian's medallion (here Fig. 68), which shows his Temple of Diva Matidia. Giuseppe Simonetta and Laura Gigli (2018 [2021], 128-129 with n. 7, pp. 164-165, Fig. 1 = here Figs. 67; 67.1) have now followed my relevant hypothesis.

5.) the course of the "Acqua Sallustiana" or of the Amnis Petronia, the Palus Caprae, and the Euripus:

Contrary to the first versions of the maps here Figs. 58; 59; 60; 62; 65, I have now added between the Thermae Agrippae and the eastern end of the Euripus an extension of the "Acqua Sallustiana" and/ or of the Amnis Petronia, which now ends at the Euripus; this water course thus emptied into it. In the first versions of our maps, this watercourse, coming down from the Fons Cati on the Quirinal, ended at the Thermae Agrippae; because I followed Filippo Coarelli's hypothesis (and still do so), according to which this water course had emptied into the (former) Palus Caprae, which he, like other scholars, has located there, assuming that it extended from there further in westerly direction; cf. Coarelli ("Petronia Amnis", in: LTUR IV [1999] 81; cf. id. 1997, 16: Fig. "2. Pianta del Campo Marzio intorno al 100", labels AMNIS PETRONIA; ARA MARTIS; VILLA PUBLICA; SAEPTA; PALUS CAPRAE); cf. here Figs. 58; 59; 60; 65; labels: QUIRINAL; FONS CATI; AMNIS PETRONIA ?; DELTA; SAEPTA; "ACQUA SALLUSTIANA" ? and/ or AMNIS PETRONIA ?; THERMAE AGRIPPAE; ( Former site of the PALUS CAPRAE ); EURIPUS.

All just-mentioned subjects are hotly debated; cf. Häuber (2017, 204-217). In this text I have declared to mark on our maps all the different suggestions concerning the identifications and locations of the topographical features in question, especially of those watercourses. And because several scholars have suggested that the watercourse discussed here emptied into the Euripus, I have now also drawn the above-mentioned addition of this watercourse accordingly.

Contrary to those scholars, Valentino Gasparini (2018, 88 with n. 61) follows Leonardi et al (2010, 86) in assuming the following: "... a series of well loggings recently drilled in the entire area of the Campus Martius seems to suggest that the amnis Petronia was probably not able to overtake the difference in altitude between the flood plain and the area of the meander, and it had likely to flow South, reaching the Tiber in front of the Tiber island [with n. 61]". Gasparini (2018, 88 with n. 61) does not discuss in this context the fact that also several earlier scholars had suggested exactly the same course of the Amnis Petronia (flowing in southerly direction, and reaching the Tiber in front of the Island) which I have, therefore, likewise drawn on our maps and discussed in my text. Nor does Gasparini (op.cit) mention the fact that (again) other scholars have rejected precisely this hypothesis.

I myself have added to this discussion the new observations that the existence of this water course, flowing in a southerly direction, is proven by lineaments in the photogrammetric data/ the current cadastre (cf. here Figs. 58; 59); cf. Häuber (2017, 208-209, 213-214). But this fact, in my opinion, does not preclude the assumption that (other) parts of the "Acqua Sallustiana"/ Amnis Petronia could have flowed in westerly direction - and then drained into the Euripus.

See for those watercourses, especially for the "Acqua Sallustiana", as well as for the Palus Caprae; also Giuseppina Pisani Sartorio (2017, 41, with ns. 56, 57, who provides further references, not discussed by myself in 2017).

When studying these subjects for my book of 2017, I have discussed the matter for a long period of time with Valentino Gasparini. He then and now in his relevant publication (2018, 90-91), in my opinion convincingly, suggests that it was not Agrippa, who created the Euripus, as had hitherto been taken for granted, but already Pompeius Magnus. Gasparini kindly allowed me at the time to quote passages verbatim from his own relevant manuscript in advance of publication, and.I have also followed some of his ideas. See now Gasparini ("Bringing the East Home to Rome. Pompey the Great and the Euripus of the Campus Martius", 2018). Because Gasparini (2018) does not mention our relevant discussions, nor addresses the relevant observations, made in my published text (2017), I repeat in the following, the relevant results, which I maintain here.

Cf. Häuber (2017, 212):

"At about the same time, Valentino Gasparini has mentioned to me in a telephone conversation the fact that R. Leonardi, S. Pracchia, S. Buonaguro, M. Laudato and N. Saviane (2010) have formulated different hypotheses concerning the Palus Caprae than those mentioned above. Since I am a) not a geologist myself, and b) the publication by R. Leonardi et al. 2010 has caused a very lively discussion, I refrain from trying to summarize all these new findings in this context.

On the other hand, the toponym `chiavica´ of the Church of S. Lucia della Chiavica/ del Gonfalone obviously refers to a man-made hydraulic installation, which, if true, could mean that the Romans had drained the Palus Caprae by means of several channels (as in the case of the drained swamps personally known to me), and likewise described for Rome by A. Corazza and L. Lombardi (1995, 181). It is certainly worth while to study Coarelli's two `emissarii´ and the very location and the strange course of the Euripus under that perspective as well. Although Valentino Gasparini tells me that R. Leonardi et al. (2010) suggest instead that the Euripus functioned as `imissario´ of the Palus Caprae, since they explain the depression, indicated by the toponyms of the Churches of S. Andrea della Valle, and of the Chiesa Nuova/ S. Maria in Vallicella [for both Churches; cf. here Fig. 59] differently than hitherto assumed.

All these hypotheses concerning the geology of the area just-mentioned, could, of course, only be proven, provided the Euripus had been sloping down from the north-west to the south-east. The seeming paradox alone, when looking on a map, on which the Euripus is marked (cf. here Figs. 3.5; 3.7 [= here Figs. 58; 59]), that this water course emptied into the Tiber upstream (instead of flowing downstream), cannot, in my opinion, really be judged, as long as the original landscape of the area in question has not been reconstructed in all its relevant details [my emphasis]".

Whereas Gasparini (2018, 88-89, with ns. 63-69) follows the hypothesis of Leonardi et al. (2010) that the Euripus served the purpose of leading water of the Tiber, `from west to east´, into the Campus Martius; most other scholars suggest that the water of the Euripus flowed in the opposite direction (`from east to west´), and thus emptied into the Tiber.

In my earlier study of 2017, I have quoted the opinions of scholars concerning the above-mentioned topics, who come from very different disciplines, which is why in many of these cases, those scholars did not know of each other's research. Therefore, these very complex interrelated problems can, in my opinion, only be solved, once all those available data are considered together, and that by a group of competent scholars who come from all those disciplines.

After having written this down, I discussed the matter with Franz Xaver Schütz, especially Gasparini's (2018, 88-89) hypothesis, according to which the water in the Euripus flowed `from west to east´ into the Campus Martius. A hypothesis which, as I have stated in (2017, 212, quoted verbatim supra) could only be verified, `as soon as the original landscape of the area in question has been reconstructed in all its relevant details´.

Franz Xaver Schütz told me on that occasion that he intends to create precisely that, a DTM (`digital terrain model´) of the Campus Martius, using for this visualization of the ancient landscape my map here Fig. 59; cf. Franz Xaver Schütz (FORTVNA PAPERS, vol. I);

6.) The Clivus Capitolinus, leading from the Forum Romanum to the Area Capitolina on the Capitolium:

Contrary to the first version of our map Fig. 3.5 of 2017 (= for the updated map; cf. here Fig. 58), I have now reconstructed the last section of the Clivus Capitolinus differently, by drawing it as a curve. The reason being that it occcurred to me that visitors to the Area Capitolina (the sacred Precinct of the Temple of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus) would thus have been able to see the façade of this temple in front of them, when approaching it. Unfortunately this part of the Clivus Capitolnus is not preserved, due to a landslide. For the Area Capitolina and the Clivus Capitolinus, which led to it; cf. Häuber (2005, 18-21, 41-42, with Abb. 2-5 (= here Figs. 74-76 and Fig. 73). See here Fig. 73, for a documentation of the small preserved part of the Clivus Capitolinus. As explained in detail in Häuber (2005, 18-55, Abb. 2-5 = here Figs. 73-76), I myself refrain from drawing a reconstruction of the Area Capitolina on the Capitolium - contrary to many other scholars, whose hypotheses I have discussed and mapped in this article.

As I only realize now, already Filippo Coarelli has drawn the Clivus Capitolnus ending with a similar curve (cf. LTUR I [1993] 432, "Fig. 126. Campus Martius. Pianta del c. M. [Campus Martius] in età augustea (da F. Coarelli [i.e., here F. COARELLI 1983a], in Città e architettura [1983], 43)".

7.) The main entrance of Domitian's Palace on the Palatine, the Domus Augustana.

Contrary to the first version of our map Fig. 3.5 of 2017 (= for the updated map; cf. here Fig. 58), I have now adapted that detail of the north side of the ground-plan of the Domus Augustana, where its main entrance was located, and which is very badly preserved. I have corrected this detail according to the most recent findings, published posthumously by the late Ulrike Wulf-Rheidt (2020, 185, Fig. 1). In the first versions of our maps, we had drawn the ground-plan of the Domus Augustana after the map SAR 1985. For a detailed discussion of this subject; cf. supra, at Chapter The major results of this book on Domitian (`Die wichtigsten Ergebnisse dieses Buches über Domitian´).

Datenschutzerklärung | Impressum