"The colossal marble statue (to be identified with here Fig. 5.3 or Fig. 5.5?), seen by Poggio Bracciolini at a site that turns out to have belonged to the Iseum Campense

On pp. 235-246, with Fig. 3 [portrait of "Gian Francesco Poggio Bracciolini [1380-1459] (da J.-J. BOISSARD, Bibliotheca chalcographica, I-IV,

Heidelberg 1669, Cc 3)"], Arata (2011-2012) discusses a passage from Poggio Bracciolini's work De varietate fortunae. This text was written between 1432 and

1435 (or around 1440), and is of great interest to our context discussed here. On p. 238, Arata (2011-2012), suggests a different reading of a crucial detail of this

passage. Arata combines this with further hypotheses, which he has already published in an earlier article (cf. Arata 1999). In Häuber (2014), I have rejected the

latter hypotheses, adding further pertaining information that Arata (1999) had overlooked (he overlooked it again in his article of 2011-2012). In order to be able to

judge the situation, Arata's new and old hypotheses, in my opinion, should be re-

-------------------------------------------------------------- 136

considered together with my ideas (cf. Häuber 2014), but lack of time prevents me

from trying to provide myself a synthesis in this context. In order to facilitate further research, the relevant conlusions, at which I had arrived in Häuber (2014),

will be summarized below, cf. p. 324ff.

In n. 20, Arata (2011-2012, 235-236) quotes for Poggio Bracciolini inter alia Jean-Yves Boriaud 1999, and in n. 21 the publication, from which he has copied Poggio Bracciolini's text: Outi Merisalo 1993, "Lib. i.II. 122-130, p. 94".

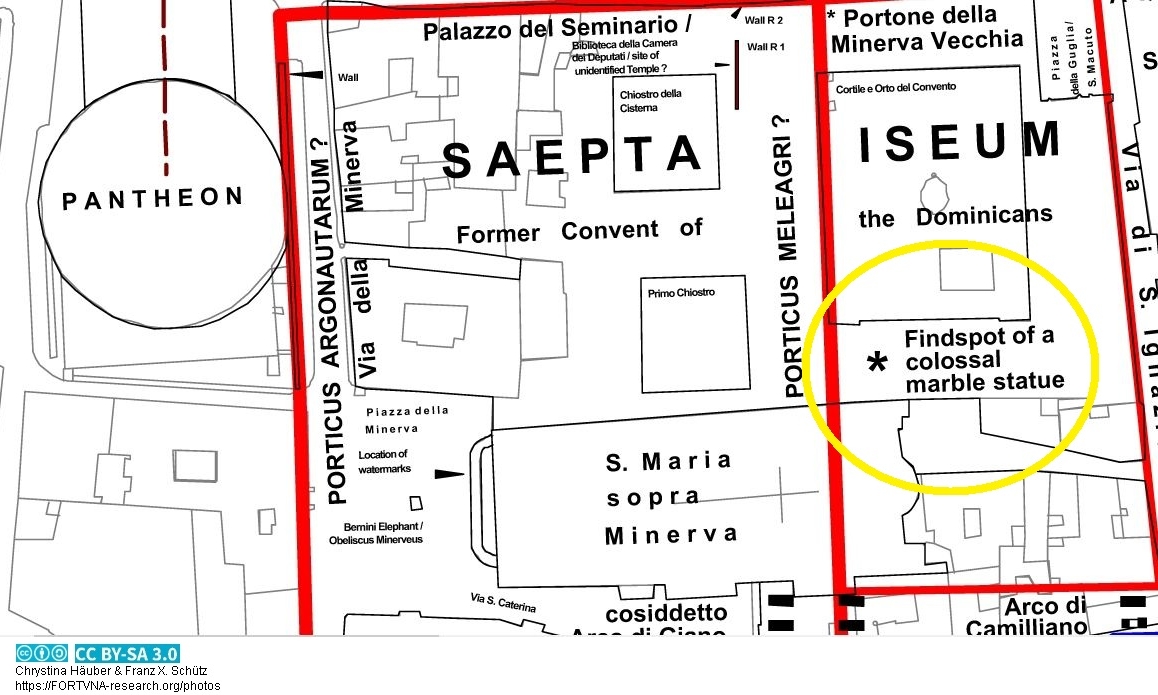

In the account just-mentioned, Poggio Bracciolini describes a spectacular find in the garden of a private individual, located within that area immediately to the east of the Church of S. Maria sopra Minerva, that was later likewise acquired by the Domenicans (cf. Arata 2011-2012, 241 with n. 44. Nolli's large Rome map of 1748 corroborates the assertion that this estate was later owned by the Dominicans): this find consisted in a colossal marble statue, comprising the head with its face intact ("Prope porticum Minervae statua est recubantis, cuius caput integra effigie, tantaeque magnitudinis ut signa omnia urbis excedat ..." (cf. Arata 2011-2012, 235), `next to the Porticus of [the Temple of] Minerva, there is a lying statue, the face of its head is intact, the statue's height excels that of all other [ancient] statues in Rome´. On his Fig. 4, Arata tentatively marks the findspot of this statue with a red asterisk - I have integrated this information into my maps (cf. infra).

In the past, this colossal statue has often been identified with the `Minerva Giustiniani´ at the Vatican Museums, Museo Chiaramonti, Braccio Nuovo (inv. no. 2223), 2.23 m high (followed by Häuber 2014, 110 with ns. 583-585, p. 551 with n. 18, p. 788 with n. 64; cf. B 30.). Arata 2011-2012, 239-240, rightly rejects this identification, a) because the `Minerva Giustiniani´ is too small, and b) because its head was not found together with its body. For the separately found head of the `Minerva Giustiniani´, which occurred underneath the Church of S. Marta when that was destroyed in the course of building the Collegio Romano, cf. Federico Rausa (2000, 194; Häuber 2014, 110 n. 584, p. 788 n. 64; Arata 2011-2012, 239 with n. 37; cf. here Figs. 3.7; 3.7.1; 3.7.1.1, labels: Collegio Romano; Piazza Collegio Romano; Former site of S. Marta and of the Monastero di Agostiniane; Fountain: MINERVA CHALCIDICA).

Whereas in Häuber (2014, 788 with n. 64), I have followed those who asserted that the torso of the `Minerva Giustiniani´ was found at the Church of S. Maria sopra Minerva - ignoring at the time Poggio Bracciolini's account quoted above, who described the statue found there as colossal, adding that it comprised its head - I see now that the torso of the `Minerva Giustiniani´ cannot be identified with the statue that Poggio Bracciolini saw there. The findspot of the torso of the `Minerva Giustinini´ thus remains unknown. And because the literary sources, which (seemingly) attest this findspot, turn out to be unreliable (or have been misunderstood), we should perhaps also doubt that the head of the `Minerva Giustiniani´ was found in this area.

Arata himself identifies Poggio Bracciolini's colossal marble sculpture, found to the east of the Church of S. Maria sopra Minerva, with the double life-size marble statue of Minerva at the Musei Capitolini, Palazzo Nuovo (cf. here Fig. 5.3). To this I will return below.

Contrary to A. Ten's assertion quoted above (ead. 2015, 69-70 with n. 76), Arata (2011-2012, 237 with ns. 22-26) does not identify Poggio Bracciolini's Temple of Minerva with the Temple of Minerva Chalcidica. On the contrary, Arata (op.cit.), judges this old identification as erroneous, because he follows G. Gatti's reconstruction of the entire area in question, that comprises the location of the (alleged) Temple of Minerva Chalcidica to the south-east of the Iseum Campense. As we shall see in the following, this (alleged) Temple of Minerva Chalcidica was in reality a fountain (cf. here Figs. 3.7; 3.7.1; 3.7.1.1, labels: ISEUM; Fountain: MINERVA CHALCIDICA).

Arata (2011-2012, 236-237, 243-244 with n. 50) rather identifies Poggio Bracciolini's Temple of Minerva, found close to the Church of S. Maria sopra Minerva, with the Delubrum Pompei.

For Poggio Bracciolini, as well as critical comments on his personality and work, cf. Susanna Le Pera (2014, 68-70). On p. 68, she writes: "Serious study of the topography of Roma began with a controversial figure and his unscrupulous actions. The humanist Giovanni Francesco Poggio Bracciolini ....", giving in the following many examples of his `unscrupulous actions´ (my emphasis).

Already in his earlier article, Arata (1999) had suggested that this statue of Minerva (Fig. 5.3) should be identified as the cult-image of the Delubrum Pompei. In Häuber (2014, 600, 784-785, 787, 793), I have rejected this idea, because it is not even certain that the Delubrum Pompei ever existed, and if so, whether it stood at Rome. For the Delubrum Pompei, cf. also J. Albers (2013, 254).

In an important detail, Poggio Bracciolini's account concerning the statue he saw near the Church of S. Maria Minerva, has been interpreted in two different ways (cf. infra). Arata provides a new (i.e., the second) reading: according to his reading of this report, Poggio Bracciolini described a statue of Minerva. Arata tries to support his suggestions that a) the statue found near S. Maria sopra Minerva represented Minerva, and b) that it should be identified with the statue of Minerva at the Musei Capitolini, Palazzo Nuovo (cf. here Fig. 5.3), by adducing further arguments.

1.) On p. 243, Arata (2011-2012) states that, provided the statue actually represented Minerva, this fact could explain the toponym of the Church of S. Maria sopra Minerva. Arata (op.cit.) does not discuss Mario Torelli (2004), who has, in my opinion, convincingly explained that the toponym `sopra Minerva´ of that Church derives from the colossal statue of Minerva standing on top of the fountain Minerva Chalcidica, that the Emperor Domitian had erected to the south-east of the Iseum Campense (cf. here Figs. 3.7: 3.7.1; 3.7.1.1, labels: ISEUM; Fountain: MINERVA CHALCIDICA). For the (alleged) Temple of Minerva Chalcidica, cf. also J. Albers (2013, 154, 155, Figs. 80; 81, pp. 175, 209, 253-254, but note that he likewise does not discuss M. Torelli 2004).

2.) On p. 244 with Fig. 6, Arata (2011-2012) suggests that the statue of Minerva (Fig. 5.3) is represented under the central archway of the `Arcus ad Isis´, that is known from one of the reliefs from the tomb of the Haterii (cf. here Fig. 5.4), which Arata (op.cit.), like most other scholars identifies with the Arco di Camilliano. The former Arco di Camilliano stood to the south-east of the Iseum Campense (cf. here Figs. 3.7; 3.7.1; 3.7.1.1, label: Arco di Camilliano). The suggested identification of the `Arcus ad Isis´ with the Arco di Camilliano is also mentioned by J. Albers (2013, 228), who mentions also critical voices, who have rejected this identification.

In Häuber (2014), I have summarized the relevant discussion and hope to have demonstrated that the `Arcus ad Isis´ cannot possibly be identified with the Arco di Camilliano. This hypotheses was followed by Eric M. Moormann (2015, 261). To all of this I will return in more detail below; cf. infra, pp. 324ff.; 337ff.

Contrary to Arata (2011-20122, 235 with ns. 19, 20), I do not think that Poggio Bracciolini's report on a find at the Convent of the Dominicans, next to the Church of S. Maria sopra Minerva, necessarily means that the statue in question represented the goddess Minerva. As already mentioned, Arata (2011-2012) suggests on p.

238 a new reading of this passage. In the past, this detail of Poggio Bracciolini's account has been translated differently, leaving the identification

of the represented divinity (?) open (see my above offered translation of this passage on p. 137); cf. Arata (2011-2012, 236-237).

If Poggio Bracciolini intended to say, what earlier scholars have taken for granted, this could mean, that he left on purpose the

subject matter of the sculpture, he described, open (or simply forgot to mention it). And if it is also true, what I tentatively suggest in the following, namely,

that this statue represented the goddess Isis, Poggio Bracciolini's relevant decision could be explained by the assumption that the iconography of the statue was

unknown to him.

By looking at the plan, published by Arata (2011-2012, Fig. 4), the findspot, which he suggests for Poggio Bracciolini's colossal marble statue, turns out to be located within the Iseum Campense (cf. here Figs. 3.7; 3.7.1; 3.7.1.1, labels: ISEUM; * Findspot of a colossal marble statue), a fact, which Arata (2011-2012) himself does not address. Arata (2011-2012, 240, 244-245) writes that he has so far not found information that could explain, why and how the colossal statue, found near the Church of S. Maria sopra Minerva, ended up on the Capitoline. In order to identify the statue, found at the Iseum Campense, with the statue of Minerva on the Capitoline (,here Fig. 5.3), that was first mentioned a little bit more than 100 years after the colossal statue had occurred at the Iseum Campense, he needs these missing links, of course. One of the arguments, adduced by Arata (2011-2012, 243) in order to identify both statues, lies in the fact that he does not know another candidate, with which the colossal statue, found at the Iseum Campense, could possibly be identified. But note that, according to Arata (op.cit.), the colossal statue, found at the Iseum Campense, represented Minerva, an assumption, which he, in my opinion, has not proven so far.

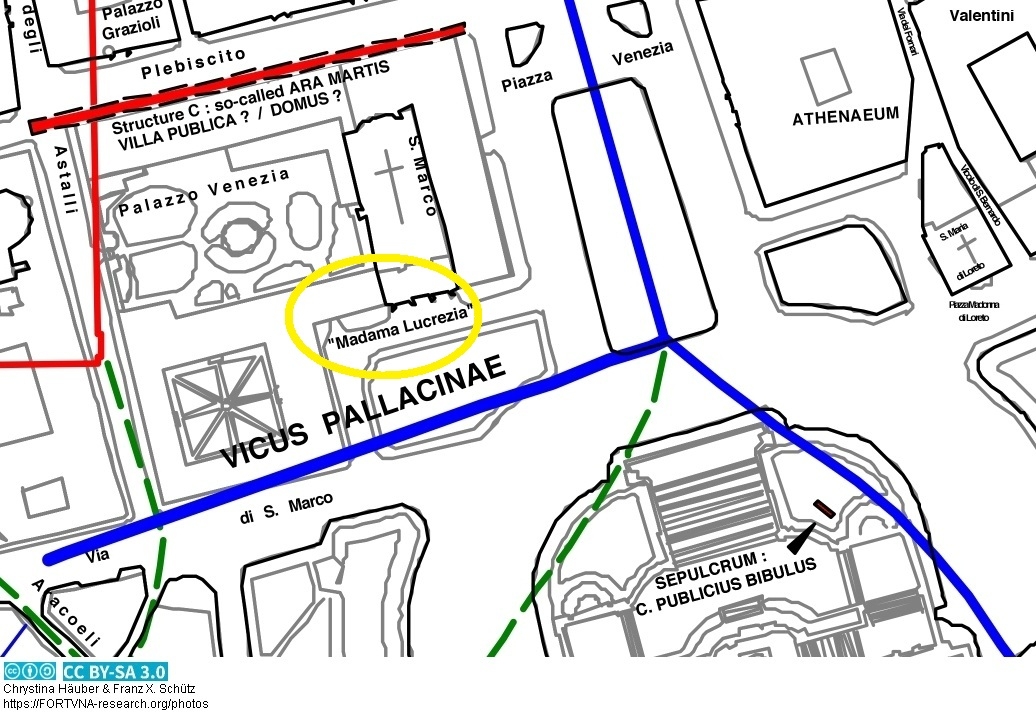

In my opinion, there is a possible candidate. Considering a) the findspot of this colossal marble statue within the Iseum Campense, as well as the facts that b) Poggio Bracciolini does not say to have seen a seated colossal statue; c) that the statue he saw was (in his opinion) the tallest ancient statue at the time extant in Rome; that d) the statue he saw comprised its head; and e) that in the case of my candidate the findspot is so far unknown, I tentatively identify the (seemingly) lost statue, found at the Iseum Campense, with the fragmentary colossal statue of a standing Isis, better known as "Madama Lucrezia" (cf. here Fig. 5.5).

Already many other scholars have attributed the "Madama Lucrezia" to the Iseum Campense - in very different ways. In their attempts to reconstruct the statue's original context, some scholars have asserted that the "Madama Lucrezia" represented the goddess Isis seated. This is not true: Johannes Eingartner (1999, 23-24; cf. Häuber 2014, 157 with n. 73) has seen that the "Madama Lucrezia", when intact, was instead a standing statue. For a detailed discussion, cf. Häuber (2014, 156-158 with ns. 63-81).

Currently, the "Madama Lucrezia" is on display in the corner of the Piazza di S. Marco near the Palazzo Venezia (cf. here Figs. 3.7; 3.7.1, labels: Palazzo Venezia; "Madama Lucrezia"), where it was brought by Cardinal Lorenzo Cybo around 1500 (so TCI-guide Roma 1999, 200). According to J. Eingartner (1991, 115, cat. no. 15, pl. XIV, with references), the statue is known since 1465, Katja Lembke (1994, 220, cat.no. E 9, pl. 28,3 [corr.: pl. 28,1], writes: "Herkunft unbekannt; seit etwa 1465 vor S. Marco". The head of "Madama Lucrezia" is 55 cm high (cf. Lembke, op.cit.), the remaining fragment of the statue is 2.28 m high (cf. Eingartner 1991, op.cit.). The "Madama Lucrezia" was thus originally much taller than the statue of Minerva (here Fig. 5.3), which is intact and `only´ 3.29 m high, that is to say, double life-size (cf. Häuber 2014, 703 with n. 92, p. 784 with n. 4). Let's now return to Tens's discussion of Alfano's hypotheses, and to her critique of G. Gatti's `mosaico´."

-------------------------------------------------------------- 140zu FORTVNA PAPERS 2 incl. download des kompletten Bandes

Datenschutzerklärung | Impressum