Diese Ergänzungen haben folgenden Titel:

Folgende weitere Abbildungen aus C. Häuber 1998a und 2014, die zu diesem Text gehören, werden hier abgebildet:

Abb. 1): Häuber 1998a, 85, Abb. 2; 3; Häuber 2014, 33, Fig. 7:

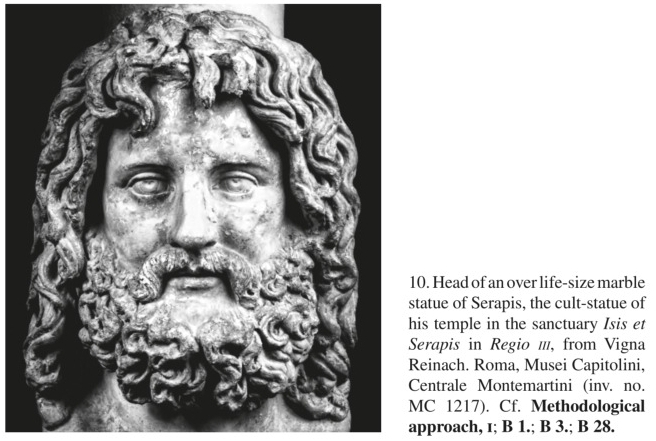

"7. Drawing from the `Paper Museum´ of Cassiano dal Pozzo, coffered ceiling. Represented are: Isis-Fortuna [die thronende Göttin] and Minerva, Harpocrates and a worshipper, doves and dancing men. Drawn in the sanctuary Isis et Serapis in Regio III. Windsor Castle, Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013 (inv. no. RL 11398). Cf. Methodological approach, I; II.2.; II.6.; B 32".

In unserm Aufsatz (2001, Seite 292, fig. 10) ist vom Fund eines großen Marmorfüllhorns die Rede, das im Jahre 1890 auf dem Esquilin in Rom, in der ehemaligen "Vigna Cappuccini", beim Bau der Via Buonarroti (heute: Via Angelo Poliziano), zu Tage gekommen ist. Im BullCom 18 (1890, 305, 341, Nr. 1) und in den NSc (1890, 282), ist der Fund dieses `großen Marmorfüllhorns´ angezeigt. Der Fundort befand sich im Bereich der antiken `Porticus mit Piscina´, die ich mit dem ägyptischen Heiligtum Isis et Serapis der augusteischen Regio III identifiziere.

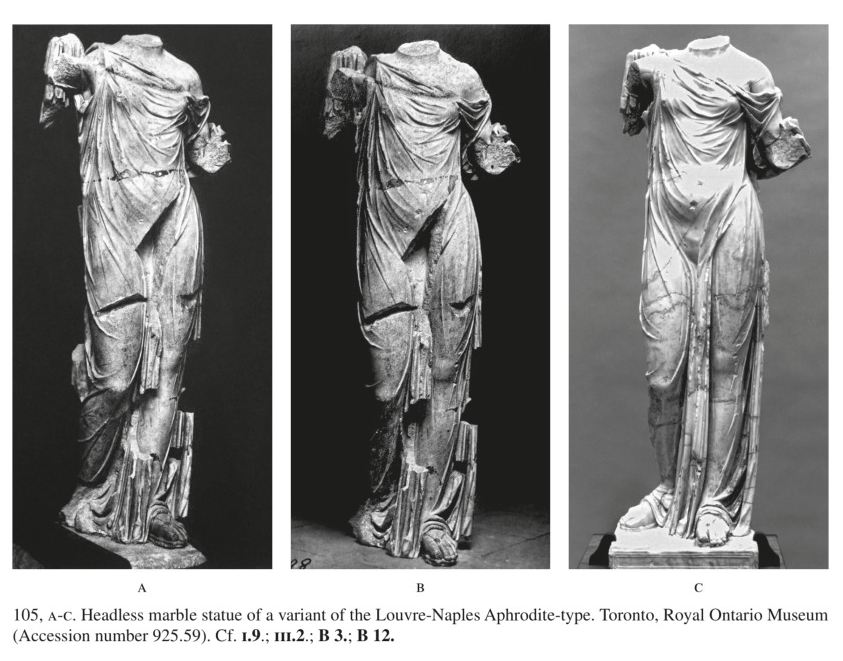

Glücklicherweise wurde das Marmorfüllhorn zusammen gefunden und beschrieben mit den Fragmenten des Marmortorsos einer Variante der `Aphrodite Louvre-Neapel´, die ich mit dem Torso dieses Aphroditetyps im Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto (Accession mumber 925.59; vgl. C. Häuber 2014, 471, Fig. 105A-C; hier Abb. 5) identifizieren konnte. Da diese Aphroditestatue lebensgroß ist und das Füllhorn in den Fundnotizen als `größer als diese Statue´ beschrieben wurde, wird es zu einer überlebensgroßen Statue gehört haben.

Dieses Marmorfüllhorn ist heute verschollen. Wegen seiner Größe kann es theoretisch zur Statue einer im Heiligtum Isis et Serapis der Regio III verehrten Gottheit gehört haben, zum Beispiel zum Kultbild der Isis-Fortuna, die, wie wir wissen, in diesem Heiligtum verehrt worden ist (vgl. C. HÄUBER 2014, 33, Fig. 7; hier Abb. 1).

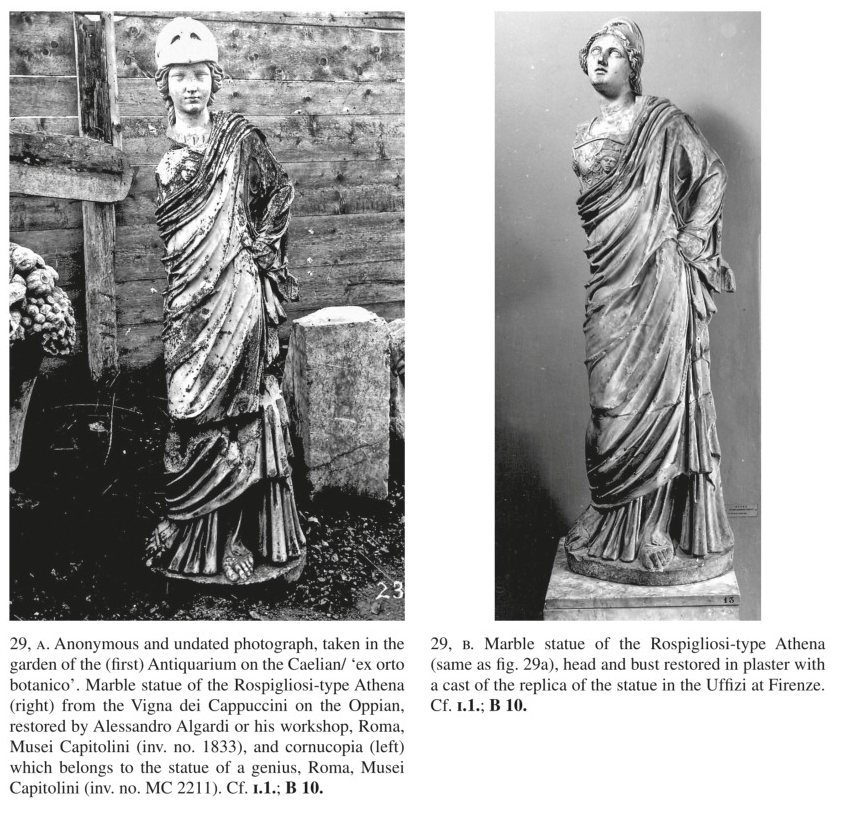

In unserem Aufsatz 2001 und in späteren Diskussionen bin ich (Häuber) irrtümlich davon ausgegangen, dass dieses Marmofüllhorn auf einem (undatierten) Photo sichtbar sei (vergleiche C. HÄUBER 2014, 141, Fig. 29a; hier Abb. 4), das im Garten des (ersten) ehemaligen Antiquariums auf dem Caelius entstanden ist. Und zwar deshalb, weil auf diesem Photo der antike Torso der Athena Rospigliosi in den Musei Capitolini (Inv. Nr. 1833; mit ergänzter Büste des Alessandro Algardi), neben einem Marmorfüllhorn erscheint (das ich irrtümlich mit dem gesuchten Füllhorn identifiziert habe). Von diesem Athenatorso wissen wir nämlich, dass er gleichfalls aus der Vigna der Cappuccini stammte, das heißt, vom selben Fundort auf dem Esquilin wie das verschollene Füllhorn.

Inzwischen (im September 2008) konnte ich, dank der bewährten und tatkräftigen Unterstützung der Freunde in den Kapitolinischen Museen: Claudio Parisi Presicce, Maddalena Cima und Emilia Talamo, herausfinden, dass das Füllhorn auf dem Photo (hier Abb. 4) zur Statue eines Genius (!) gehört (Musei Capitolini, Inv. Nr. MC 2211), die sich im giardino des Palazzo Caffarelli befindet.

Trotz meiner abenteuerlichen Irrtümer rund um dieses verschollene Marmorfüllhorn bleibt natürlich die Frage bestehen, wessen Attribut dieses Marmorfüllhorn tatsächlich gewesen ist.

Ich habe deshalb im Folgenden das kurze Kapitel kopiert, in dem nicht nur meine Irrtümer zu diesem Marmorfüllhorn aufgeklärt sind (siehe unten, Anmerkung 23), sondern in dem auch alle übrigen Marmorstatuen aufgezählt sind (u.a. hier Abb. 2; Abb. 3), die in der Gegend des Heiligtums Isis et Serapis der Regio III entdeckt worden sind, und die ich zum Teil für die in diesen Heiligtümern aufgestellten Kultbilder halte, beziehungsweise, die uns eine Vorstellung von diesen Kultbildern vermitteln können.

Dieser Text ist in meiner Monographie erschienen: The Eastern Part of the Mons Oppius in Rome. The Sanctuary of Isis et Serapis in Regio III, the Temples of Minerva Medica, Fortuna Virgo and Dea Syria, and the Horti of Maecenas, 22. Suppl. BullCom, S. 509-513, und wird hier nach meinem Originalmanuskript abgedruckt, mit einigen Änderungen: Die Querverweise in den Fußnoten zu anderen Teilen in diesem Band habe ich aus der gedruckten Version des Buches übernommen.

Für die Bibliography dieses Buches vergleiche diesen link"B 3.) The fragmentary cult-statues of the sanctuary Isis et Serapis in Regio III

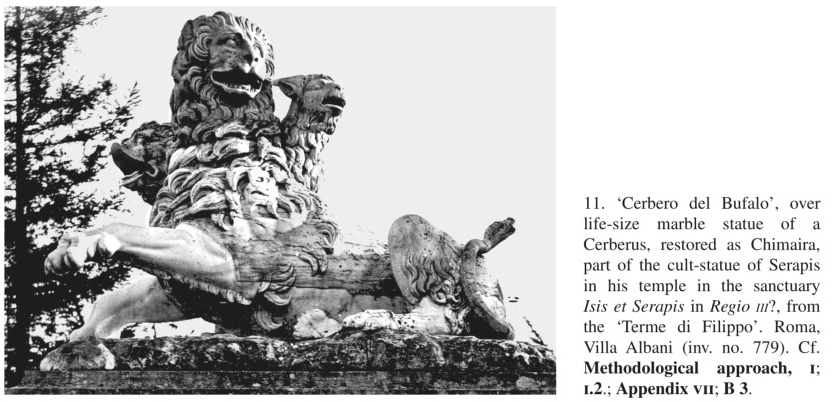

Roger Ling and Mariette de Vos did not know that fragments of over life-size marble sculptures were found in the area of the sanctuary Isis et Serapis in Regio III, which we have elsewhere tentatively identified with the cult-statues worshipped in this sanctuary of the Egyptian gods1. Pirro Ligorio recorded the find of the over life-size `Cerbero del Bufalo´ (fig. 11 [hier Abb. 3]; cf. I.2.; Appendix VII) in the `Terme di Filippo´/ the substructure on Via Pasquale Villari (maps 1; 2; 17; 18); this sculpture probably belonged to a cult-statue of Serapis. But because the `Terme di Filippo´ are drawn as portico quadrato on many reconstructions of ancient Rome, Ligorio may have seen the `Cerbero´ in the `Porticus with Piscina´ instead; cf. Appendix III.

This statue (fig. 11 [hier Abb. 3]), which is datable to the Antonine period2, is in my opinion the only replica (or rather variant, since there is no serpent entwined around the three animal forms) of the Aion of the `Macrobian type´3 (Macrobius, Sat. 1.20.13ff.) in over life-size of the cult-statue in the Alexandrian Serapeion, (allegedly) created by the Athenian artist Bryaxis of the 4th century BC; all the other replicas are statuettes. In this I follow Léon Homo's suggestion of 18984. In the meantime, the artist Bryaxis of the 4th century BC is no longer regarded as the author of this famous cult image, nor is this cult image still dated in the 4th or in the 3rd century BC, but in the 1st century BC instead; cf. B 26.). Sally-Ann Ashton and Mafoud Ferroukhi go even further than that by denying a Hellenistic prototype for the numerous copies of the cult-statue of Serapis: "The attributes associated with Serapis in the Ptolemaic period are a lotus crown, beard and carefully divided fringes. It is only later in the Roman period that the god is shown with a modius and is accompanied by the dog Cerberus"5. Note that already Lollio Barberi, Parola and Toti6 were of the opinion that Commodus had ordered the iconographic type of Serapis with fringes.

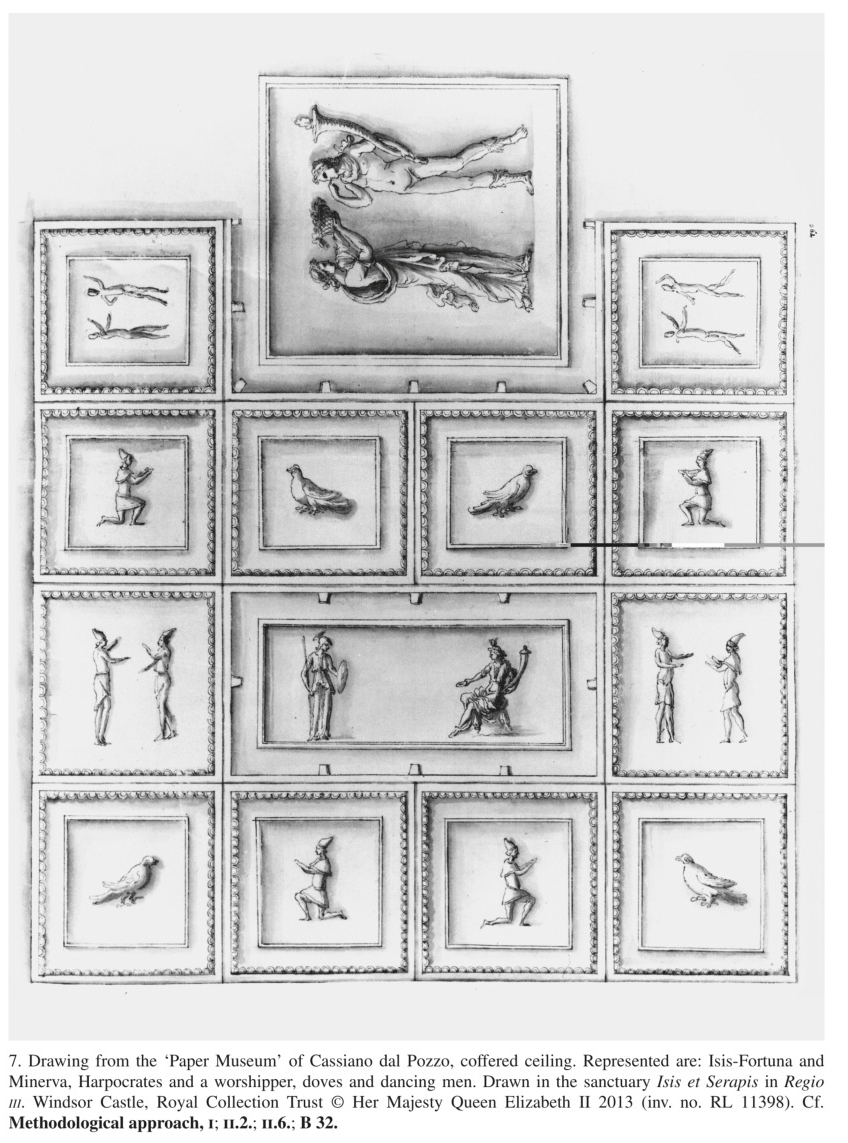

If so, this would mean that our Cerberus (fig. 11 [hier Abb. 3]) was copied after a Roman creation of a Serapis with Cerberus. A likewise over life-size head of Serapis (fig. 10 [hier Abb. 2])7, which had probably [page 510] belonged to a cult-statue, was found in 1886 in the `statue walls´ of the former Vigna Reinach (maps 2; 3; 17; 18, label: Statues); the provenance of this sculpture was previously unknown. So far another head in the Musei Capitolini is usually identified with the head of Serapis found in the former Vigna Reinach. This old identification is wrong, since Carlo Pietrangeli described this head as follows: "Nella parte superiore della testa è una profonda incassatura per l'inserzione del modio, ora mancante"8, `on the top of the head there is a socket9, into which the separately worked modius, now lost, was set´.

The head of Serapis from the Oppian (fig. 10 [hier Abb. 2]) is the only one in the Musei Capitolini lacking its modius which has a flat area for its addition. This, its statue-type, and the fact that it had belonged to a statue, matches Visconti's10 description of the head found in the former Vigna Reinach: "Giove Serapide, o Plutone ... già parte di una statua. È del tipo consueto (Museo Pio-clement. 2, 1). Sull'alto del capo rimane una parte piana, destinata a ricevere il modio, forse di metallo. Marmo greco, buona scultura". Note that according to Visconti11 this head was smaller than life-size, but since Lanciani12 mentioned among those finds some heads `of quasi colossal proportions´, I believe my identification is nevertheless correct. Since the sculptures from the Vigna Reinach were acquired by the Comune and at first deposited in the `Auditorium of Maecenas´13, the head of Serapis found there must belong to the collections of the Musei Capitolini. The head of Serapis from the Oppian was in the former `Sala ottagona´ of the Palazzo dei Conservatori14, and is listed in a Rome guide published in 1889 which described the statues on display there15. This means that this sculpture was excavated or purchased by the Commissione Archeologica before 188916.

Serena Ensoli Vittozzi17 has recognized that the modius of our head (fig. 10 [hier Abb. 2]) is a modern restoration, and she dates this head stylistically in the time of Commodus (cf. B. 28)). Ulrike Egelhaaf-Gaiser18 makes the following suggestion concerning this head (fig. 10 [hier Abb. 2]): the statue (?) of Serapis "Kapitolin. Museen Inv. 217, die vermutlich aus den Trajansthermen [here map 3, label: Baths of Trajan] stammt, sollte eventuell auf die Nähe des Iseum Metellinum aufmerksam machen". The head of the cult-statue of Serapis from the Oppian (fig. 10 [hier Abb. 2]) is like the `Cerbero del Bufalo´ [hier Abb. 3] a creation which differs significantly from other heads of Serapis that are commonly regarded as copies of the cult-statue in the Alexandrian Serapeion, attributed to Bryaxis; cf. B. 26.). It is tempting to believe that both sculptures (figs. 10; 11 [hier Abb. 2; 3]) originally belonged together and that both were commissioned by Commodus.

The `Cerbero del Bufalo´ (fig. 11 [hier Abb. 3]), this head of Serapis (fig. 10 [hier Abb. 2]) and the inscription ISIS E[t Serapis] (CIL VI, 35571)19, the latter two found in `statue walls´ in the former Vigna Reinach, are the only archaeological proofs20 that Serapis [page 511] was worshipped in this Egyptian sanctuary of the Oppian (maps 3; 17, label: Vigna XII Apostoli/ Reinach, the findspot is marked with the label: STATUES). We do not know whether or not Isis and Serapis were worshipped together in the sanctuary of Regio III from the beginning, given its name Isis et Serapis in the `Constantinian´ regionary catalogues. But Serapis is missing in the two drawings of the stucco-work decoration of this temple (figs. 7 [hier Abb. 1]; 8), dating to the Neronian period (cf. II.6.), and on the reliefs of the Arcus ad Isis (fig. 117a) which in my opinion stood close to the sanctuary Isis et Serapis in Regio III, replacing the Porta Querquetulana in the Servian city wall (maps 3; 17; labels: Servian city Wall; PORTA QUERQUETULANA/ ARCUS AD ISIS). The marble decoration of the tomb of the Haterii, to which this relief once belonged, has been dated between the late Flavian period and 120 AD21. As for the aedituus templi Serapei22, we cannot know whether the temple in question was the one in the sanctuary Isis et Serapis of Regio III.

In addition to the fragmentary over life-size cult-statue of Serapis (figs. 10 and 11? [hier Abb. 2; 3]), there is a chance that a fragment of an over life-size cult-statue of Isis-Fortuna was also documented by the excavators of the 19th century. I am referring to the "grande cornucopia marmorea"23 found together with the statue now in the Royal Ontario Museum at Toronto (figs. 105a-c [hier Abb. 5]; cf. B 12.)), but belonging to a different sculpture. Unfortunately the cornucopia was not measured. But since the author of the relevant report in the Notizie degli Scavi described it as "grande", its proportions were obviously larger than those of the headless statue (figs. 105a-c [hier Abb. 5]), which is life-size. Since this cornucopia belonged to an over life-size statue, it may in theory have belonged to the cult-statue of Isis-Fortuna, as drawn in the temple on the Oppian (fig. 7 [hier Abb. 1]), which is probably also represented on the marble base (fig. 9a).

This is only a hypothesis, since the cornucopia is not documented on photographs, and its current whereabouts is unknown. The cornucopia was found while building Via Buonarroti/ Angelo Poliziano), in the former garden of the Capuchin monks, the area of the `Porticus with Piscina´ (maps 3; 17; fig. 100). De Vos, who had not herself identified the relevant statue (here figs. 105a-c [hier Abb. 5]), believes that this lost cornucopia could have belonged to a statue of Fortuna, and [page 512] Marroni24, who is also unaware of the fact that the statue (here figs. 105a-c [hier Abb. 5]) has been identified in the meantime, tentatively suggests an identification of this alleged statue of Fortuna with Isis. If my suggestion is true that the lost cornucopia had belonged to a cult-statue of (Isis-)Fortuna, this would be one of the few statues of Fortuna datable in the imperial period recorded for this area25; we may for example wonder whether the statue of Isis-Fortuna (fig. 115)26 from the late antique `Lararium´ on Via Giovanni Lanza (map 3, labels: Via G. Lanza; ISIS-FORTUNA "Lararium"), and the Egyptianizing statuettes worshipped there together with it, had originally been dedicated in the sanctury Isis et Serapis in Regio III. If true, this could (in theory) support my hypothesis that the mid-Republican (but possibly archaic) shrine on the old Via Curva/ Carlo Botta, the cult of which survived until the imperial period, should be identified with the temple of Fortuna Virgo. If the cornucopia was indeed part of a cult-statue of Isis-Fortuna, this would identify the `Porticus with Piscina´ with the area of the temple of Isis in the Egyptian sanctuary. Note that I identify a fragmentary statue found in the former Vigna Reinach (fig. 3; B 1.)) as an Isis-Fortuna. [page 513]

The distribution of those finds, a fragment of the cult-statue of Isis-Fortuna from the `Porticus with Piscina´ (if that should be true), the head of the cult-statue of Serapis from the former Vigna Reinach, and the Cerberos/ Aion, belonging to the cult-statue of Serapis from the `Terme di Filippo´ [hier Abb. 2; 3] (or from the `Porticus with Piscina´?; maps 3, 17, labels; ISIS ET SERAPIS, "Porticus with Piscina", Forum Petronius Maximus; Isis et Serapis Regio III/ Forum Petronius Maximus?; 58a-d "Terme di Filippo"; a), would then prove the reconstruction of the sanctuary Isis et Serapis in Regio III, as suggested by Lanciani and de Vos, in the most beautiful fashion. Even without the assumption that the lost cornucopia had belonged to the cult-statue of Isis-Fortuna, their suggestion is proved, since at least fragments of the over life-size cult-statue of Serapis (figs. 10 and 11? [hier Abb. 2; 3]) from his temple in the sanctuary Isis et Serapis in Regio III are now known, and are recorded to have been found within the areas of two buildings adjacent to the `Porticus with Piscina´ (or actually within the `Porticus with Piscina´). Finally it cannot be ruled out that this "grande cornucopia marmorea" could have belonged to a statue of the Egyptian god Harpocrates, who was also worshipped in the sanctuary Isis et Serapis, as shown by the coffered ceiling of the stucco-work decoration (fig. 7 [hier Abb. 1]), where he holds a cornucopia in his left arm. It is, of course, also possible that this cornucopia had belonged to a statue of Serapis, or to yet another god or personification.

Be all that as it may, since the excavators of the 19th century27 had, very understandably, not suggested in the two short notes published on this cornucopia that it could (in theory) have been part of a statue of one of the Egyptian gods, Lanciani28 and everyone else ever since could be of the opinion that no single Egyptian or Egyptianizing sculpture had been found by the `excavators´ of his time within the area of the `Porticus with Piscina´. Because it is now proved that Petronius Maximus built his Forum at the site of the `Porticus with Piscina´ (cf. I.7.), we may assume that he changed the previous building accordingly. This, taken together with the Aegyptiaca discussed here and in the chapters I.1; I.5; B 1.); B 4.); B 16.); B 19.), and also those discussed in the chapters B 25.); B 27.); B 29.), allows the conclusion that the `Porticus with Piscina´ was part of the sanctuary Isis et Serapis in Regio III. It further explains why the excavators of the late 19th and 20th centuries did not find anything there which looked like temples of Isis and Serapis".

------------1 Schütz, Häuber 2001, p. 292, figs. 10; 11 (but note that the identification of the cornucopia was wrong, see below).

2 Cf. supra, p. 76, n. 250.

3 The `Cerbero del Bufalo´ is not listed in the LIMC; cf. S. Woodford Spier, s.v. Kerberos, c) "Macrobian" types, in LIMC VI 1, 1992, pp. 30-31; cf. M. Le Glay, s.v. Aion-Chronos, in LIMC I, 1981, p. 410; cf. for the Serapis of Bryaxis: Leclant 1997, pp. 25-26.

4 Homo 1898, passim; cf. Wrede 1982, p. 5 n. 30.

5 S.-A. ASHTON, M. FERROUKHI, s.v. Marble head of Sarapis, in WALKER, HIGGS 2001, p. 73, cat. no. 52.

6 Lollio Barberi, Parola, Toti 1995, p. 46.

7 Last autopsy: September 24th, 2008. I thank Giuseppina Bruscia for accompanying me. Roma, Musei Capitolini, Centrale Montemartini (inv. no. MC 1217), head from an over-lifesize statue of Serapis, marble, 61 cm high; head without modius 44 cm high. H. Stuart Jones, Pal. Cons., pp. 261-262, Scala VI 5, pl. 102; Pietrangeli 1951, p. 33 cat. no. 22, suggested date: Antonine period; he says about the alleged provenance given by Stuart Jones for this head: "dice erroneamente che proviene dal Larario di S. Martino ai Monti"; HÄUBER 1991, p. 186 no. 218.

8 PIETRANGELI 1951, p. 30 no. 13; Malaise 1972a, p. 173 cat. no. Rome 315f.; De Vos 1997, p. 124 n. 302.

9 For the relevant technique, cf. CLARIDGE 1990.

10 C.L. Visconti 1887, p. 133 no. 1, p. 354 no. 5.

11 C.L. Visconti 1887, p. 133 no. 1, p. 354 no. 5: "Testa minore alquanto del vero ... alta cent. 18".

12 R. Lanciani, in NSc 1887, p. 140: "... Sono state recuperate circa venti teste di statue, alcuna delle quali di proporzioni quasi colossali ...".

13 C.L. VISCONTI 1887, pp. 132, 136.

14 Häuber 1991, p. 186, Sala ottagona no. 218 ("provenance unknown").

15 MEYERS REISEBÜCHER 1889, Sp. 175, 2nd line from the bottom: "Sarapiskopf".

16 Cf. Häuber 1991, p. 149.

17 Ensoli Vittozzi 1993, p. 234 ns. 60-64, fig. 74; ead. 1997, p. 576 n. 1. She suggested in both publications that this head was found in the `Lararium´ on Via Giovanni Lanza (here map 3, labels: Via G. Lanza; "Lararium"). After I had sent her an earlier version of this text, she did not mention the head of Serapis among the finds from the `Lararium´ any more; cf. ENSOLI 2000a, pp. 280-282, 287 figs. 22-24; cf. p. 518, cat. no. 147; cf. M.P. Del Moro, in op. cit.[i.e., in: ENSOLI, LA ROCCA 2000], pp. 518-524, cat. nos. 146, 148-160.

18 Egelhaaf-Gaiser 2000, p. 383 with n. 177.

19 Cf. supra, p. 4 n. 28.

20 PIETRANGELI 1951, p. 28 no. 8, suggested that the statuette of Serapis with Cerberus "Trovata nell 1812 nell'area delle Terme di Traiano; proviene forse dall'Iseo della III regione"; cf. for that, Appendix VII.

21 Cf. supra, p. 170 n. 178.

22 Cf. supra, p. 55 n. 40.

23 Cf. BCom XVIII, 1890, pp. 305, 341, no. 1; p. 305 (here the erroneous opinion is expressed that this cornucopia and the female headless statue, here figs. 105a-c [hier Abb. 5], belonged together and were part of a statue of Fortuna); NSc 1890, 282 (here the cornucopia is correctly identified as belonging to another statue): "Presso la via Buonarroti [today: Via A. Poliziano], nell area dell'antica Vigna dei Cappucini ... È stata pure trovata nello stesso luogo [i.e. like the statue here figs. 105a-c = hier Abb. 5] la parte superiore di una grande cornucopia marmorea, ricolma di frutti, che doveva essere sostenuta da un altro simulacro, come simbolo di fertilità e di abbondanza". By judging from these short descriptions it seems clear that nothing survived of the statue to which the cornucopia once belonged. Earlier I had erroneously suggested that this cornucopia is visible on the photograph here fig. 29a [hier Abb. 4], together with the Rospigliosi-type Athena from the Vigna dei Cappucini, when both sculptures were in the former `Orto Botanico´, the garden of the first Antiquarium Comunale on the Caelian (cf. here map 3). But because this cornucopia is not standing on the ground, I was wondering whether it could belong to a statue, to which it is still attached but that is not visible on the photograph. This is in fact true. This cornucopia belongs to the fragmentary statue of a genius in the giardino of Palazzo Caffarelli (Musei Capitolini, inv. no. MC 2211); MUSTILLI 1939, p. 175 n. 57, pl. 104, 396, marble, 1, 10 m high. I thank Claudio Parisi Presicce, Emilia Talamo and Maddalena Cima, whose combined efforts in September of 2008 helped me finally to identify the cornucopia of this photograph; cf. Häuber 1991, pp. 326-327, cat. nos. 21, 22; ead. 1998a, p. 107, ns. 123, 124, figs. 5; 9; ead. 2001, pp. 85-87, fig. 17a,b (with erroneous reconstruction of this cornucopia as part of a standing statue of Tyche-Fortuna/ Dea Syria?); Schütz, Häuber 2001, p. 292, fig. 10 right (with erroneous assumption that it was part of the cult-statues of the temple of the Egyptian cults discussed here); Häuber, Schütz 2004, pp. 136-141 (with erroneous reconstruction as part of a standing statue of Isis-Fortuna (?)).

24 The excavation note referring to this statue is also mentioned by DE VOS, 1997, p. 125 with n. 313; and MARRONI 2010, p. 112 with n. 311 ("una statua di Fortuna con cornucopia, forse identificabile con Iside"), both of whom quote BCom XVIII, 1890, p. 305, but do not identify this statue.

25 Cf. for the marble statue of Fortuna of the Claudia Iusta-type (Musei Capitolini, inv. no MC 925), found near-by, on modern Via Merulana at the Church of S. Antonio di Padova; later the marble bust of Augustus (Musei Capitolini, inv. no. MC 495) was found in its vicinity (cf. map 3, labels: Collegio S. Antonio; S. Antonio di Padova, the findspot is marked: AUGUSTUS; FORTUNA); cf. PESCI 1964, p. 8: "La chiesa di S. Antonio di Padova con l'annesso Collegio dei frati minori ... si erge dinanzi alla chiesa dei Ss. Marcellino e Pietro ... e fu consacrata nel 1887". It was built by the architect Luca Carimini (p. 9) for the "Ministro generale dei frati minori con la sua curia", who from June 26th, 1250-November 29th, 1885 "aveva avuto la sede in S. Maria in Aracoeli sul Campidoglio". The ground-plan of the Flavian or Trajanic domus with later building phases, found next to the Collegio di S. Antonio di Padova on Via Merulana, where the sculptures occurred, does not appear on the FUR (fol. 31; map 2); Lanciani shows only the ground-plan of an adjacent ancient building, labelled: Scavi 6. VI. 1884; for a detailed discussion of the find of both sculptures and of the architectural remains mentioned here, cf. COLINI 1944, pp. 70, 310-311; cf. HÄUBER 1991, p. 160 no. 164 (for both sculptures); ead. 1998a, p. 107 n. 123, fig. 10,1 (Fortuna); DE VOS 1997, p. 120 with ns. 278, 279 (both sculptures), fig. 192 (Augustus), p. 134 with n. 372. On p. 120 she writes that finds comprising the statue of Fortuna and the bust of Augustus "... con ogni probabilità appartengono all'iseum dell'Oppio"; contra: LING 2000, p. 544; cf. COATES-STEPHENS 2001, p. 227 n. 21, p. 237, his Appendix no. 18; P. SCHOLLMEYER, in P.C. BOL IV 2010, p. 23, Abb. 23 (Augustus); M. CADARIO, in LA ROCCA, PARISI PRESICCE, LO MONACO 2011, p. 262, cat. no. 4.9, "Ritratto di Augusto con corona´"; LA ROCCA et alii 2013, p. 163, cat. no. II.14.2. Busto di Augusto (M. SZEWCZYK). Birgit Bergmann 2012, p. 271, identifies the wreath worn by Augustus as corona Etrusca; the original portrait of which this is a copy "was created for an honorary statue of Augustus voted by the senate after his return to Rome 19 B.C., following the recovery of the ensigns that Crassus had lost to the Parthians in 53 B.C.". On p. 272 n. 2 she asserts that the (correct) indication of the findspot of this bust of Augustus by BOSCHUNG 1993, p. 120 and M. PAPINI, in LA ROCCA, TORTORELLA 2008, p. 187: "gegenüber von SS. Marcellino e Pietro" (cf. here map 3, label: SS. Pietro e Marcellino), is wrong, erroneously assuming that they have misunderstood C.L. VISCONTI's description of the findspot; cf. BCom XVII, 1889, p. 140: "quasi dirimpetto alla nuova chiesa ed al monistero di s. Antonio". Here Visconti refers to the find-report on the statue of Fortuna; cf. BCom XV, 1887, p. 107: "Facendosi lavori per l'allargamento della via Merulana, in prossimità della nuova chiesa di s. Antonio". Note that at that stage the Via Merulana was enlarged only on its eastern side; cf. FUR (fols. 23, 30; map 2.); HÄUBER 1990b, p. 27, fig. 11, Karte 1 (= here fig. 23), where that is indicated.

26 Inv. no. MC 928, 1, 46 m high; cf. Ensoli Vittozzi 1993, pp. 222-224, cat. no. 1, figs. 56, 57, 59, suggested date: early Antonine period; ead. 1997, pp. 576-89, cat. nos. VI.47-VI.55; ead. 2000, pp. 280-282, 287 figs. 22-24; p. 518, cat. no. 147; M.P. Del Moro, in op.cit. [i.e., in: ENSOLI, LA ROCCA 2000], pp. 518-524, cat. nos. 146, 148-160; cf. J. Calzini Gysens, s.v. Isis-Fortuna, Lararium (Via G. Lanza; Reg. V), in LTUR III, 1996, p. 115 fig. 76; MARRONI 2010, pp. 100-105, pls. VIII-XI, fig. 2, no. 26. "Isis Fortuna (lararium) - V Regio augustea (tav. XXIX)"; SPINOLA 2013, p. 54; cf. on this statue of Isis-Tyche-Fortuna: Häuber, Schütz 2004, pp. 136-141 figs. II.27-II.29; FRAIOLI 2012, p. 336 with n. 270, fig. 101; VORSTER 2012/2013, p. 472 n. 315, p. 478 with n. 351.

27 BCom XVIII, 1890, pp. 305, 341, no. 1 and NSc 1890, p. 282.

28 Cf. supra, p. 51 n. 5.

Datenschutzerklärung | Impressum