Chrystina Häuber

The Horti of Maecenas on the Esquiline in Rome. My research since March 23, 1981:

Errors, funny stories and successes

The notes are to be found at the end of the text.

I had been searching for a dissertation project since 1975. By March 2, 1981, the fifth topic had also proven unfeasible, so I returned to the third: ``[translated from the German:] The statue decoration of the Horti Sallustiani in Rome´´. My friend Demetrios Michaelides at the British School at Rome, who asked me my reasons on March 19, 1981, mentioned the offer from Eugenio La Rocca, then director of the Musei Capitolini, to research the statues from the Horti of Maecenas. Since Demetrios was unable to realize this project himself, he generously suggested that I approach La Rocca about this topic - which turned out to be a saving idea for me. On March 23, 1981, I therefore visited Eugenio La Rocca in his office:

"[translated from the German:] On March 23, 1981, Eugenio La Rocca offered me a topic to work on, which, after consultation with my doctoral supervisor [Andreas Linfert], was to become my dissertation topic. I first identified the provenances of the new finds made by the Commissione Archeologica in Rome [the Archaeological Superintendency of the City of Rome] after 1870, most of which were in the Musei Capitolini, and earlier also in the Antiquarium Comunale on the Caelius, and then, building on this, studied [translated from the German:] ``The statue decoration of the Horti Maecenatis and of the Horti Lamiani on the Esquiline´´ [note 1].

In the catalogues of the Palazzo dei Conservatori of the Musei Capitolini by Henry Stuart Jones (1926), and of the "Museo Mussolini" (later called `Museo Nuovo Capitolino´) by Domenico Mustilli (1939), it is stated for many of these new discoveries (after 1870) that their provenance is unknown [note 2].

The ‘new method’ that I would have used in working on my dissertation topic, as Eugenio La Rocca called it (on 23 May 2015) [note 3], was a result of my many conversations in Rome (until September 1985) with him, Filippo Coarelli, Amanda Claridge, T.P. Wiseman and Lucos Cozzas, the latter of whom gave me the following good advice: ‘You must read everything, then you sometimes have the feeling of slipping into this time like in a glove’.

After reading some early excavation reports in the BullCom and the NSc, I decided to proceed chronologically with the excavators in my study of all these excavation reports (after 1870). In this way, the provenances of these new finds did indeed become clear to me. But only because I was also the first to use the photographs from the Parker Collection, dated 1874 and showing 65 of these newly excavated ancient sculptures, as well as many other photographs of these new finds (see below), as `dating sources´.

In the "Sala ottagona", a temporary wooden exhibition pavilion erected in the former kitchen garden of the Conservatori (located between the Palazzo dei Conservatori and the Palazzo Caffarelli, which are both part of the Musei Capitolini), which existed until 1903, the Commissione Archeologica exhibited 133 of these ancient sculptures newly discovered in its excavations at its opening on February 26, 1876. After the destruction of the "Sala ottagona", a "giardino alla Romana" was built in its place.

Right at the beginning of our collaboration, Eugenio La Rocca provided me with the printed speech by Rodolfo Lanciani from the library of the Musei Capitolini, which he had delivered at the opening of the "Sala ottagona" as First Secretary of the Commissione Archeologica (`Director of the Archaeological Superintendency of the City of Rome´). This printed speech by Lanciani includes a plan of the "Sala ottagona", showing the positions of all 133 ancient sculptures exhibited there at the opening, as well as a list of these pieces and their provenances. La Rocca also gave me two photographs from this library, taken in the "Sala ottagona".

Unfortunately, the Commissione Archeologica did not photographically document the statues in the "Sala ottagona", which were to be supplemented by many additional ancient sculptures found in further excavations until 1903.

However, numerous freelance photographers did, and I found their photographs in Roman archives. In these photos, taken in the "Sala ottagona" between 1876 and 1903, I was able to identify a total of 235 of these sculptures, newly discovered in excavations by the Commissione Archeologica (after 1870).

In addition to the aim of subsequently determining the provenance of these new discoveries (after 1870), which was achieved in this way, this procedure also produced another result: I have summarized the working methods of the employees of the two Archaeological Superintendencies in Rome (after 1870 [that of the City of Rome and that of the State]) in my `Topographical Manifesto´ [note 4] (see below, in Section III.).

As we will see below, not only the aforementioned scholars Eugenio La Rocca, Filippo Coarelli, Amanda Claridge, T.P. Wiseman, and Lucos Cozza have provided me with sustained support in the development of the Horti des Maecenas project. For this, I am deeply grateful to all of them .

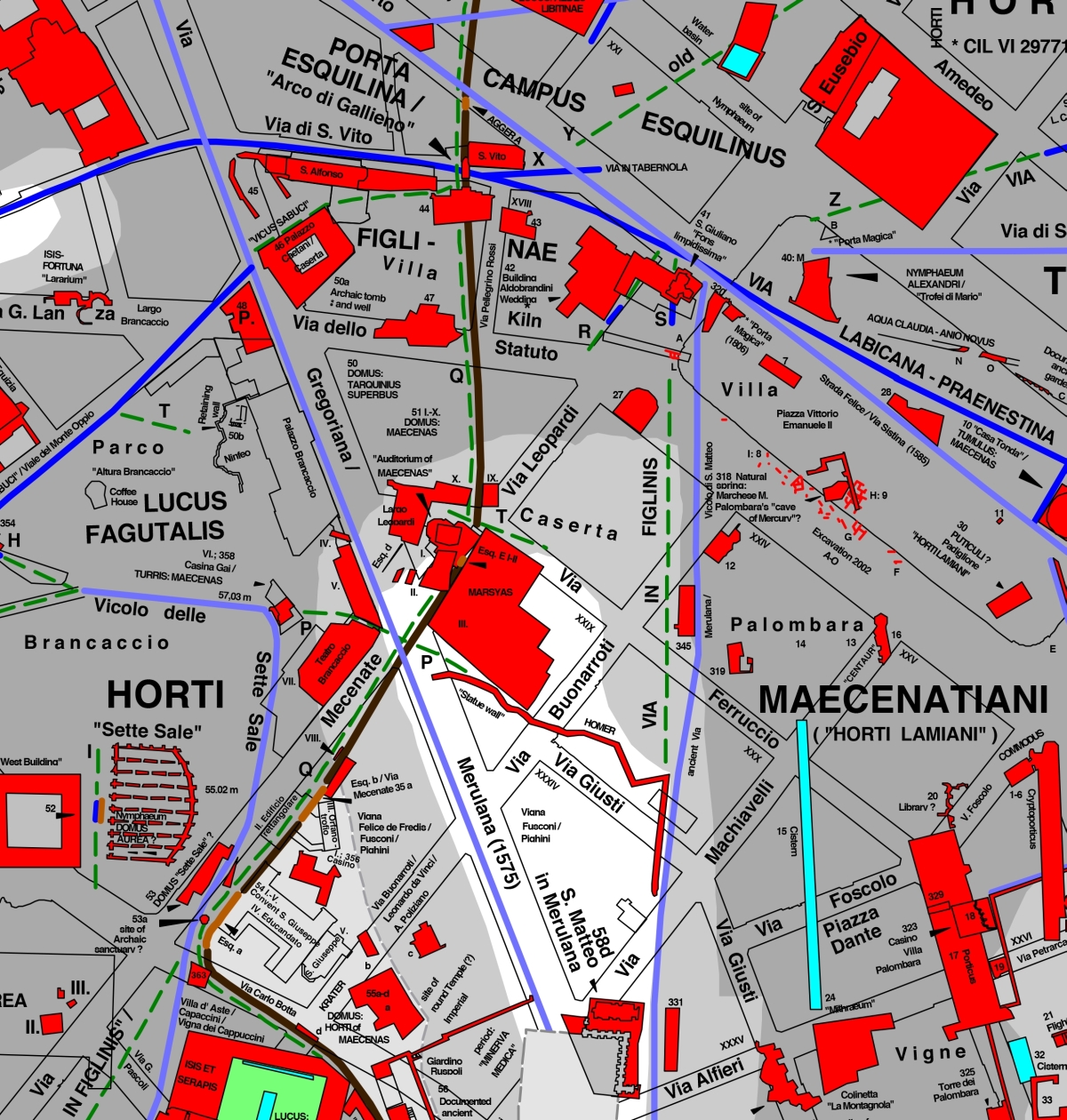

I. The section of the Servian city Wall in Via Mecenate 35a, here Fig. 1; 3

Let us now turn to those colleagues and friends who helped me study a section of the so-called Servian city Wall in Via Mecenate No. 35a (Fig. 3), as well as those who supported me concerning finds (here Figs. 4; 5) from an Augustan Domus on what is now Via Angelo Poliziano (in my catalogue of ancient structures in the Horti of Maecenas, Nos. 55a-d; a; b; c; d; KRATER). Both structures can be precisely located and are marked on our diachronic topographical map (Fig. 2) [note 5].

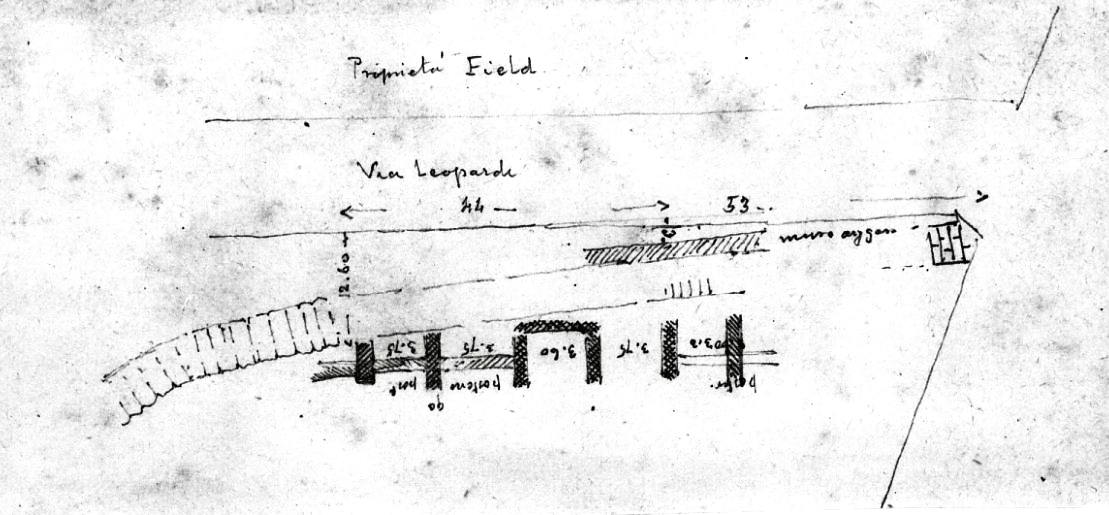

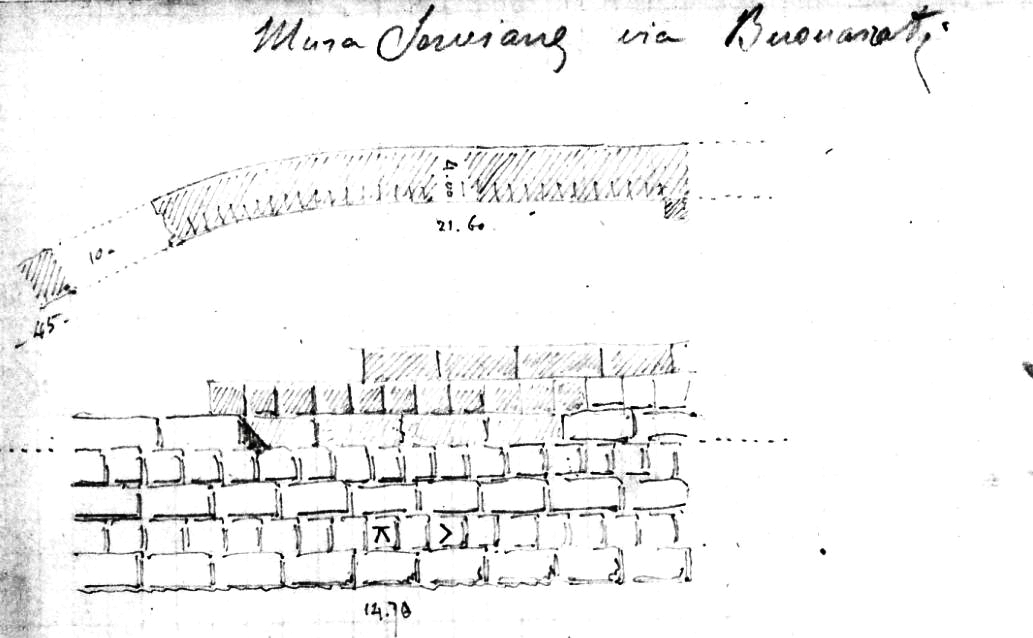

Although two sections of the Servian city Wall in this area were newly excavated at this time and documented by Lanciani personally in excavation drawings (here Fig. 1) [note 6], they are incorrectly depicted and placed in Lanciani's map Forma Urbis Romae (FUR, fols. 23; 30).

The first to recognize these facts was the legendary expert on Roman urban topography, Lucos Cozza, who, generous as he was, shared them with all his colleagues and friends, including me [note 7]. I then also studied this topic, later together with Franz Xaver Schütz [note 8].

Fig. 1. Rodolfo Lanciani, two excavation drawings in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana (Cod.Vat.Lat . 13944 f. 20 recto), which document the two newly excavated sections of the Servian city Wall on the Mons Oppius. From: HÄUBER 2014, p. 140, Fig. 26. The caption reads: "R. Lanciani, two drawings. Above: section of the Servian city Wall found in 1885 in the building site of Via Leopardi (today Via Mecenate no. 35a = SÄFLUND's [1932] cat. no. Esq. b / Via Mecenate 35a). Below: section of the Servian city Wall found in 1884 in the building site of the convent [now: Istituto] of S. Giuseppe di Cluny on Via Buonarroti (today Via A. Poliziano no. 38 = SÄFLUND's [1932] cat. no. Esq. a © 2013 Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana".

Two articles by Romana de Angelis Bertolotti (1983 and 1991) have also proven particularly important for the reconstruction of the topography of this area [note 9]. The latter article shows, for example, that all four of the new buildings erected by Luca Carimini for this monastery (after 1883) had to be built on 20 m deep foundations. From this fact, it can be concluded that Maecenas had already ordered the creation of this artificial terrace in this area [note 10] (compare the light grey area, bordered by a dashed line, on our map Fig. 2). Furthermore, a plan published by de Angelis Bertolotti (dated 1896) of the new building of the monastery, called `Edificio rettangolare´ (the `rectangular building´), erected by Carimini, shows that the southwestern part of the section of the city wall Esq. b / Via Mecenate 35a had been integrated into the foundations of this building [note 11] (compare here Fig. 2).

On the basis of this plan of the `54 II. Edificio rettangolare´ in the monastery of the Suore di S. Giuseppe di Cluny (Fig. 2) from 1896, published by de Angelis Bertolotti [note 12], Franz Xaver Schütz and I have suggested a new reconstruction of the course of the Servian city Wall in this area [note 13].

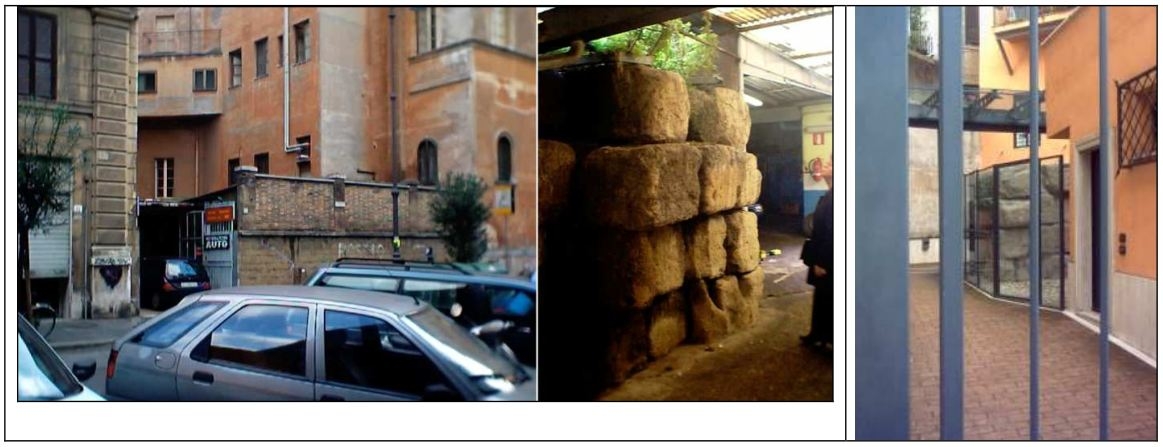

The nuns had commissioned their architect Luca Carimini to design one of their four new buildings as an 'Orfanotrofio' (an Orphanage for War Orphans) (Fig. 2). Since, thank God, there are no more war orphans in the late 20th/ early 21st century (at least in Italy), the nuns have recently had the 'Orfanotrofio' converted into a building with expensive apartments, with its entrance on Via Mecenate No. 35a. The courtyard of this building, which formerly housed a car repair shop and through which the northeastern part of the section of the city wall Esq. b / Via Mecenate 35a is accessible, was 'renovated' at the same time. Franz Xaver Schütz, who studied these changes, is a geographer, and geographers call such processes 'gentrification' [note 14].

Fig. 2. "Diachronic topographical map of Rome: Roman Forum to Mons Oppius", detail: The Horti of Maecenas on the Mons Oppius, which belongs to the Esquiline.

This map section shows the buildings mentioned in the text: The "Palazzo Brancaccio" (built between 1886 and 1908-12) on the modern "Via Gregoriana/Merulana"/ corner of "Largo Brancaccio," built according to plans by Luca Carimini (1830-1890) for the American Mrs. Mary Elizabeth Bradhurst Field (New York 1824-February 18, 1897 Rome) as Palazzo Field, with the "Teatro Brancaccio" and the "Parco Brancaccio," with the "Coffee House." The Palazzo Field was temporarily called Palazzo Field-Brancaccio and later Palazzo Brancaccio. An ancient architecture was integrated into the Palazzo Field (now Brancaccio), which has the number 48 in the catalogue of ancient structures in the Horti of Maecenas, and is therefore marked in red: "48 P.[re-Palazzo Brancaccio]".

The Palazzo Brancaccio literally stands on the main Domus/ `Palace´ of Maecenas in his Horti: "HORTI MAECENATIANI," which was built on three different terraces; see the inscription "51 I.-X. DOMUS: MAECENAS". Opposite the Palazzo Brancaccio, on the "Largo Leopardi," is the "I. Auditorium of Maecenas"; the `Tower of Maecenas´ stood on the highest terrace of the Horti in the Parco Brancaccio: "VI.; 358 [= its number in the `Catasto Pio Gregoriano´, 1866] Casina Gai / TURRIS: MAECENAS"; south of the Palazzo Brancaccio, at the corner of "Via Merulana" and "Via Mecenate," is the "VII. Teatro Brancaccio."

Furthermore, the section of the Servian city Wall "Esq. b/ Via Mecenate 35a" (here Fig. 3), located in the courtyard of the house at "Via Mecenate" No. 35a, whose southwestern part has been integrated into the foundations of one of the five buildings of the Convent of the Nuns of St. Giuseppe di Cluny, "Via Angelo Poliziano" No. 38 (today: Istituto S. Giuseppe di Cluny, which operates a hotel in the old convent); see the inscription: "54 I.-V. Convent S. Giuseppe"; this is the building erected by Luca Carimini: "II. Edificio rettangolare" on "Via Mecenate".

See also the other buildings belonging to this monastery: "I.; 356 [= its number in the `Catasto Pio Gregoriano´, 1866] Casino", which was integrated into an ancient (hence red) building; as well as the buildings built by Luca Carimini, just like the Edificio rettangolare, (after 1883): "III. Orfanotrofio" (`Orphanage for War Orphans´); "IV. Educandato (the convent building for the nuns)"; as well as the church: "V. S. Giuseppe";

and finally, the Augustan Domus in the Horti of Maecenas, previously invisible above ground, excavated only in 1883 during the construction of the "Via Buonarroti/ Leonardo da Vinci/ A. Poliziano" and destroyed immediately after the excavation; see the inscriptions: "DOMUS: HORTI of MAECENAS; 55a-d; a; b; c; d; KRATER".

In my opinion, Felice de Fredis accidentally discovered in 1506 in this Augustan Domus the Laocoon group in the Vatican Museums while excavating in his vineyard for a fountain; compare the inscription of his vigna: "Vigna Felice de Fredis/ Fusconi/ Pighini"; while from 1883 onwards, fragments of the "Torello Brancaccio" in the Palazzo Altemps (here Fig. 4) and the Portrait of Livia in the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest (here Fig. 5) were discovered in the ancient ´statue walls´ of this Domus, which until then had been located on a property that had also belonged to the American Mrs. Mary Elizabeth Bradhurst Field.

Chrystina Häuber and Franz Xaver Schütz, reconstruction 2025, with the "AIS ROMA," based on the official photogrammetric data of the Comune di Roma (now Roma Capitale), generously made available to us in March 1999 by the Sovraintendente ai Beni Culturali of the Comune di Roma, Prof. Eugenio La Rocca. We first published this map in C. HÄUBER 2014 as Map 3 and discussed it in the text of this book; see p. 873 (the key to this map). We have since corrected and significantly expanded it. This georeferenced map is also available online in high resolution open access; the corrections made are explained in detail in the accompanying text; see:

<https://FORTVNA-research.org/maps/HAEUBER_2022_map3_Forum_Romanum-Oppius.html>.

Fig. 3. The section of the Servian city Wall in the courtyard of the house at Via Mecenate No. 35a. In SÄFLUND's catalogue (1932, p. 41 with note 4, pl. 9,2; HÄUBER 2014, p. 57 with note 64) it has the following designation: "Esq.b/ Via Mecenate 35a" (compare here Fig. 2). From: F. SCHÜTZ (2014, p. 120, "Fig. 9. One example of `gentrification´. Rome, Via Mecenate (left: 2000, right: 2010)". Photos: F.X. SCHÜTZ.

The operator of this Carrozzeria Riparazioni AUTO, formerly located in the courtyard of Via Mecenate 35a, always very kindly assisted Amanda Claridge and me on 25 June 1988 (and on all my earlier and later visits, together with Giuseppina Pisani Sartorio and with Franz Xaver Schütz) [note 15].

Giuseppina Pisani Sartorio of the Archaeological Superintendency of the City of Rome, which was then responsible for the Esquiline Hill and was very interested in this research on the Servian city Wall, kindly authorized Amanda and me to this undertaking.

Also Giuseppina had previously examined the section of the Servian city Wall Esq. b / Via Mecenate 35a with me. Furthermore, with her exhibition and the accompanying catalogue L'Archeologia in Roma Capitale tra sterro e scavo 1983, and her invitation to Romana de Angelis Bertolotti to examine the Servian city Wall in a contribution to this catalogue, she had initiated the relevant research by Romana de Angelis Bertolotti (1983; 1991), and later also by Franz Xaver Schütz and myself (2004). Lucos Cozza had already encouraged me to do so (as mentioned above in note 7; compare HÄUBER 1990).

On June 25, 1988, Amanda [note 16] and I checked the distance of this section of the city wall from the modern Via Merulana and its distance from the Via Mecenate (then still called Via Leopardi) using a photocopy of Lanciani's drawing of the city wall Esq. b / Via Mecenate 35a (here Fig. 1, above). The result was that Lanciani's drawing was correct - but unfortunately, Lanciani's draftsmen incorrectly drew and incorrectly located this section of the wall Esq . b / Via Mecenate 35a on the FUR (fol. 23).

In November 2006, Giuseppina Pisani Sartorio and I found out that she had not been responsible for the section of the Servian city Wall Esq. b / Via Mecenate 35a (!).

In November 2006, Franz Xaver Schütz and I visited Rita Volpe of Rome's Archaeological Superintendency, who was now responsible for the Esquiline Hill. She suggested that we also report our new findings to her colleague Mariarosaria Barbera of the Archaeological Superintendency of the State, who was responsible for the Esquiline Hill. She called her, and a short time later, we were sitting across from her.

To our great surprise, Mariarosaria Barbera told us during this conversation that the Archaeological Superintendency of the State is responsible for the section of the Servian city Wall Esq. b / Via Mecenate 35a - and she laughed heartily with us about the story told here.

Mariarosaria Barbera had recently commissioned the architects Antonio Federico Caiola and Maurizio Mattella to restore the section of the Servian city Wall Esq. b / Via Mecenate 35a. This restoration confirmed the correction to Lanciani's drawing (Fig. 1, above) of the section of the city wall Esq. b / Via Mecenate 35a, which Franz Xaver Schütz and I had proposed (2004; here Fig. 2) [note 17].

Because, as Franz Xaver Schütz and I were able to see for ourselves on 22 November 2006 during a local meeting with Caiola and Mattella, which Mariarosaria Barbera had kindly organized for us, thanks to this restoration, one can now see the outside of the section of the city wall Esq. b / Via Mecenate 35a (Fig. 1, above; Fig. 2) and recognize what was previously impossible: the city wall does not have a curved course at this point, as shown in Lanciani's drawing, but is perfectly straight [note 18].

II. The 'Torello Brancaccio', here Fig. 4

In the following, we will examine two sculptures (Figs. 4; 5) that were excavated by members of the Archaeological Superintendency of Rome in the Augustan Domus in the Horti of Maecenas Nos. 55a-d (Fig. 2). They discovered this Domus on what is now Via Angelo Poliziano, on a former property belonging to the American Mrs. Mary Elizabeth Bradhurst Field.

Fig. 4. `Torello Brancaccio´, Ptolemaic or Roman statue of an Apis bull, Museo Nazionale Romano, Palazzo Altemps (Inv. No. 182594); Museo Barracco (Inv. No. 376). Dimensions in centimeters: "120 x 167 x 95 (H x L x W [= height, length, width])", compare S. MÜSKENS (2017, p. 216, No. 102, Fig. 3.3.102a). From: C. HÄUBER (2014, 139, Fig. 24). According to L. SIST RUSSO (in: D. CANDILIO et al. 2011, p. 344), the material of the `Torello´ is "granodiorite." The photo shows it after its third restoration.

Torello Brancaccio, Ptolemaic or Roman statue of an Apis bull, Museo Nazionale Romano, Palazzo Altemps (Inv. No. 182594). From: S. Curto (1978, 283-295, pls. 36-40). The photo shows the second restoration of the `Torello Brancaccio´.

To begin our study of the 'Torello Brancaccio', I would first like to quote a beautiful story about him from my book on the Laocoon, in which some of the protagonists appear who will accompany us until the end of this text [note 19]:

"[translated from the German] Lanciani was very well acquainted with Mrs. Field and her husband, and was a frequent and welcome guest in the salons to which the Fields' daughter, Principessa Elizabeth Brancaccio, invited `the crème de la crème of society´, first to the `Pre-Palazzo Brancaccio´ (cf. [below, in Section IV., note 77]), and later to the Palazzo Field-Brancaccio; compare Rodolfo Lanciani (1988, pp. 206-207 = Lanciani's Notes from Rome to the journal The Athenaeum, dated December 22nd, 1888, Vol. 3191, 855, edited by Anthony L. Cubberley 1988).

The fragment of the `Torello Brancaccio´ (compare [= here Fig. 4]) from the excavation site of the Palazzo Field/ Brancaccio

Lanciani had (1884) for example received valuable ancient finds from the family Field-Brancaccio, including a fragment of a very rare black stone, as a gift for the study collection of marble and coloured stone types that had been processed in ancient Rome, which he was in the course of building up in the Antiquarium Comunale.

Lanciani (1888; compare Cubberley 1988, p. 206) described this fragment, which had been given to him by the Field-Brancaccio family, as follows: "I had obtained, among others, a beautiful and perhaps unique piece of a purplish sort of granite, with oval spots resembling in shape and colour those of a leopard's skin. This block had been discovered, together with other fragments of statuary, under the foundations of Prince Brancaccio's palace [corr.: under the foundations of Mrs. Field's palace], Via Merulana ... [my emphasis]".

However, since this fragment "was not entirely shapeless, but worked by chisel on one side", as Lanciani wrote (1888; compare Cubberley 1988, p. 206), the family Field-Brancaccio had asked Lanciani that if further fragments of this statue should come to light, he would please return the gifted fragment. This happened 'two years later,' wrote Lanciani (1888; compare Cubberly 1988, p. 207), when in 1886 the remaining fragments of this sculpture were discovered during the excavation of the Domus 55a-d on the building site of the future Via Buonarroti/ Angelo Poliziano. As we know today, this sculpture is the Ptolemaic or Roman statue of an Apis bull, the 'Torello Brancaccio' (compare [= here Fig. 4]).

Furthermore, Lanciani also had numerous other social ties with the family Field-Brancaccio; see Häuber (2014, 212, 216-217). Lanciani, for his part, undoubtedly rendered the two ladies (mother and daughter Mary Elizabeth Field/ Brancaccio) a very great service, which was theoretically worth a lot of money, with his `expert opinions´ on these archaeological finds, such as the note mentioned in Punkt 1.) [= NSc 1885, 423; see below, in Section III.], which he promptly published in the scientific journal NSc. It was precisely this behaviour that Lanciani was then accused of in connection with the `Affare Lanciani (1889) (`the 'Lanciani Affair´) and 'cost' him both his public employments (see Chapter IV.2.7.)".

Four facts are of particular interest for my assertion that not only fragments of the ‘Torello Brancaccio’ (Fig. 4), but also the portrait of Livia (Fig. 5; see below, in Section III.) were found in the Domus No. 55a-d on the [former] property of Mrs. Field on Via A. Poliziano:

a) Rodolfo Lanciani (NSc 1885, 423) wrote that the Domus No. 55a-d (Fig. 2) was discovered on a piece of land that Signor [corr.: Signora] Field had sold [1883] to the Società dell'Esquilino, which built here, on behalf of the City of Rome, an extension of the Via Buonarroti (later: Leonardo da Vinci, today: A. Poliziano) [note 20];

b) all the sculptures unearthed on this site in 1885 and 1886 by the staff of the Archaeological Superintendency of Rome were immediately reported in the BullCom [the periodical of the Archaeological Superintendency of Rome] and in the NSc [the periodical of the Archaeological Superintendency of the State]; for example by Lanciani, who had excavated the Augustan Domus No. 55a-d together with Giuseppe Gatti [note 21] and who worked simultaneously for both Superintendencies [note 22]. According to the legal situation in force at the time, all these finds should therefore have become the property of the Musei Capitolini [note 23];

c) that Mrs. Field was nevertheless the owner of the fragments of the `Torello Brancaccio´ (Fig. 4) and of the Dioscuri relief from this property, and that the museum in Budapest was able to buy the Livia portrait (Fig. 5) from the same site in 1912, which came ``from the Palazzo Field-Brancaccio´´, shows that Mrs. Field had negotiated a special agreement with the city of Rome that all sculptures found on her former properties (on Via Angelo Poliziano 1885; 1886 and on the `extension of Via dello Statuto´/ today Largo Brancaccio, 1886) in the excavations that followed would become her property [note 24] (see for the reason for this special agreement below, in Section IV. );

d) Lanciani and Gatti wrote in 1886 that some of the statue fragments discussed here were discovered during their excavation on the building site of Via Buonarroti (today Angelo Poliziano), `about 100 m west of Via Merulana´, and therefore in the Domus no. 55a-d, in a "muraglione di fondamento, costruito con frantumi di statue e di marmi architettonici", that is to say, in a `statue wall´ [note 25] as we call it today. While Carlo Ludovico Visconti [note 26] claimed (erroneously) that the statue fragments found on the grounds of the convent of the Suore di S. Giuseppe di Cluny (Fig. 2), also in 1886, came from ‘medieval statue walls’ – an error still followed by many scholars today – we know for sure that the ‘statue walls’ found on the Esquiline were ancient [note 27].

The portrait of Livia in Budapest (Fig. 5) was discovered in 1885 during excavations in the Via Buonarroti (now Angelo Poliziano; here Fig. 2), within the Augustan Domus 55a-d; compare Rodolfo Lanciani (NSc 1885, 423) [note 28]; further statue fragments, including those of the `Torello Brancaccio´ (here Fig. 4), were unearthed there in 1886. I suggest that the Laocoon group also stood in this Domus No. 55a-d (which was not visible above ground at the time) when it was discovered in 1506 [note 29].

My sincere thanks go to two Italian colleagues in Rome who introduced us to the ‘Torello Brancaccio’ in an unusual way.

On March 3, 2014, the Egyptologist Loredana Sist announced to the Egyptologists Rafed El-Sayed and Konstantin Lakomy, Franz Xaver Schütz, and me that she had discovered a new fragment of the `Torello Brancaccio´ (here Fig. 4) in the Museo Barracco [note 30], which left us with no small amount of astonishment. This fragment undoubtedly matches the `Torello´, as Loredana explained to us: she had been allowed to take this fragment from the Museo Barracco for verification purposes, so that she could compare it with the `Torello Brancaccio´ in the Palazzo Altemps.

On March 5, 2014, the classical archaeologist Maddalena (Magda) Cima made this fragment of the `Torello Brancaccio´ available to us at the Museo Barracco. On March 3, 2014, after our conversation with Loredana, the four of us had wandered to the Palazzo Altemps to study the `Torello´, which is why we were able to confirm that Loredana was absolutely right during our on-site visit to the Museo Barracco on March 5. Magda led us into the meeting room of the Museo Barracco, where the `turned-up´ fragment of the `Torello´ lay on a piece of furniture. She then told us, with her characteristic sense of humor, that this fragment had long served (as was clearly visible) as an ashtray (!).

Magda and I spontaneously agreed that this was the most bizarre story we had ever heard about the `new discoveries from the Esquiline after 1870´.

If one turns this fragment the right way round and knows the `Torello´, which is restored in plaster at this point (Fig. 4), it becomes clear that this highly polished statue fragment belongs to his hindquarters, which, apart from the unique material from which the `Torello´ is sculpted, can be seen in the shape of the fragment and at the start of his vertically hanging tail [note 31].

When I asked if there were any plans to reinsert poor Torello's real fragment, Madga smiled and pointed out that this would be impossible simply because the Museo Barracco is a municipal museum, while the Palazzo Altemps/ Museo Nazionale Romano is a state museum (!).

My daily calendar for March 5, 2014, says [translated in English]:

"to Magda Cima, Museo Barracco - Magda is wonderful as always."

At that time I could not have imagined that this would unfortunately be our last conversation together about the `new discoveries from the Esquiline after 1870´ (!) [note 32].

In research this sculpture (Fig. 4) is called `Torello Brancaccio´ [note 33]. The fragments of the `Torello´, which were discovered in 1886 in the Domus 55a-d on Via Buonarroti (today: Via Angelo Poliziano); compare Lanciani [note 34], were immediately brought to the Pre-Palazzo Brancaccio (see below, note 77), which was to be (partially) integrated into the Palazzo Field; later this was called Palazzo Field-Brancaccio and today Palazzo Brancaccio (compare Fig. 2).

It was there that the painter Francesco Gai [note 35] restored this statue for the first time (also using the fragment of the `Torello´ discovered in 1884 in the excavation site of the Palazzo Field-Brancaccio, as well as the fragments that came to light in 1886 immediately north of the Palazzo during the construction of the `extension of the Via dello Statuto´, today Largo Brancaccio [note 36]), which was then exhibited in the Parco Brancaccio, in the Coffee House designed by Francesco Gai (here Fig. 2). Francesco Gai integrated into the brick base of the `Torello Brancaccio´ the Attic votive relief to the Dioscuri, which was discovered in 1885, together with the portrait of Livia (here Fig. 5), in the Domus 55a-d [note 37].

In 1970, the Ministero per i Beni Culturali purchased the `Torello Brancaccio´ from the Brancaccio family for the Museo Nazionale Romano. The Egyptologist Silvio Curto led the negotiations with the Brancaccio family on behalf of the Ministry; Curto [note 38] mentioned also that the Attic votive relief to the Dioscuri had also been purchased along with the `Torello´.

The Anaximander relief in the Museo Nazionale Romano, the Eudoxos relief in Budapest and presumably also the relief of an unknown philosopher in the magazzino delle sculture in the Palazzo Nuovo of the Musei Capitolini, which I published in 2014 and 2017, also originate from the imperial `statue wall´ in the Domus 55a-d, mentioned by Lanciani and Gatti (Bull Com 14 1886, 215; see notes 25, 54) [note 39].

Compare in the latter text [i.e., HÄUBER 2017] the written comments on these reliefs by R.R.R. Smith [note 40], as well as my discussion of these reliefs with Hans Rupprecht Goette [note 41], who was working on them at the time. The result is that I, like the two scholars mentioned, consider these three reliefs to be Attic and, moreover, suggest that Maecenas commissioned them for his Horti [note 42].

Hans Rupprecht Goette and Árpád Miklós Nagy [note 43] now write the following about this Eudoxos relief in Volume I of the new catalogue of the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest, of which Hans kindly presented me with a copy:

"[translated from the German:] 80 Relief image of Eudoxos, pl. 146-149, inv. 4778 ... Provenance: According to P. Arndt from Rome ... according to new research (Häuber 2014), probably from a medieval wall on the Oppius, from which the relief of Anaximander in the Museo Nazionale Romano 506 (see below) also comes; see also here cat. 73 (4134) [= here Fig. 5]. Then Arndt Collection (Munich); acquired in 1908. Date: 1st century BC".

In their `Bibliography´, Goette and Nagy cite me as follows: "Chr. Häuber, The Eastern Part of the Mons Oppius in Rome, BullCom Suppl. 22 (Rome 2014) [translated from the German:] 9f. Note 59, p. 202 Note 48". However, I did not write there (or anywhere else), as Goette and Nagy claim, that the Eudoxos and Anaximander reliefs originate from a `medieval wall´ [note 44].

III. The portrait of Livia in Budapest, here Fig. 5

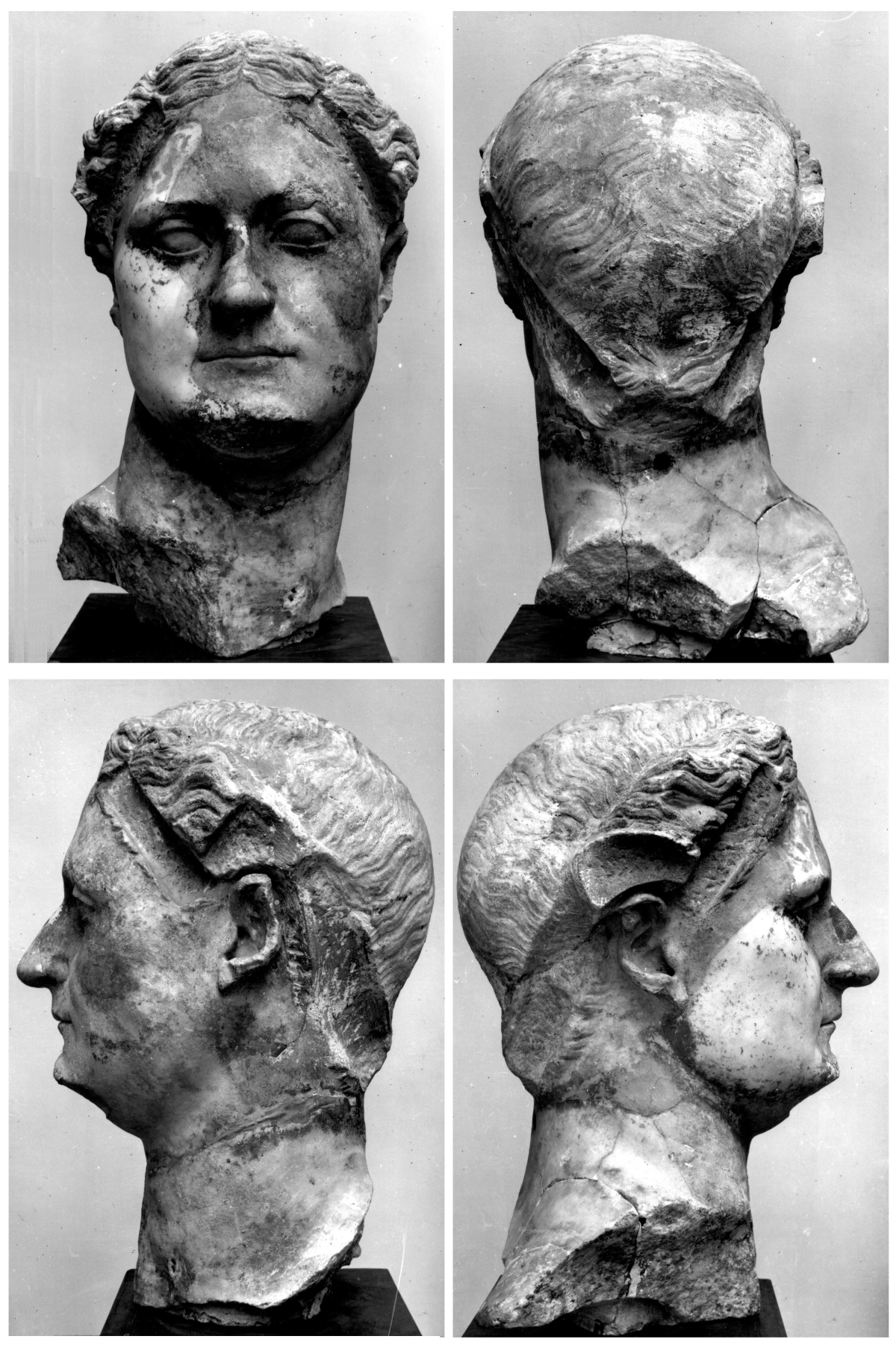

Fig. 5. Larger-than-life portrait of Livia. Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts (Inv. 4134). Compare H.R. Goette and A.M. Nagy 2024, p. 147, cat. 73: "[translated from the German:] Portrait of a Ptolemaic queen, reworked in a portrait of Livia, Parian marble (Lychnites). Height: 47 cm, chin-parting: 33,4 cm. Date: 3rd century BC / Augustan". From: C. HÄUBER (1998, Fig. 12, 1-4).

I don't know this portrait from autopsy.

When it comes to the antiquities of the family Field-Brancaccio, I have benefited for many years from the vast experience of my good friend, the art historian Gabriella Centi, who has spent decades studying this family, its palazzo, its real estate, and its antiquities. The members of this family were also very generous art sponsors and, in addition, acquired exquisite art and jewelry collections, which Gabriella is likewise interested in.

According to Lanciani (NSc 1885, 423), the following two ancient sculptures, the Dioscuri relief in the Museo Nazionale Romano, Palazzo Altemps, and a "Testa colossale, non saprei dire se di donna, ovvero d'un Bacco o d'un Apollo", came from the excavation on the former property of Mrs. Field, the Augustan Domus 55a-d on Via Buonarroti (today Via Angelo Poliziano; Fig. 2):

"Regioni IV e V. Negli sterri per l'apertura della via Buonarroti, attraverso i terreni venduti dal sig. [corr.: dalla signora; note 45] Field alla Società dell'Esquilino, a ponente di via Merulana, e nelle fondamenta delle case adiacenti, sono stati ritrovati i seguenti oggetti: Bassorilievo marmoreo, lungo m. 1,52, alto m. 0,59, con cornice piana larga m. 0,06, di eccellente disegno, e di mediocre fattura e conservazione. Procedendo da s.[inistra] verso d.[estra] le figure si succedono in quest'ordine: a) Dioscuro ignudo, seduto su d'una rupe, sulla quale è distesa la clamide: la d.[estra] riposa presso il torace, la sin.[istra] sollevata in alto regge la lancia: nel fondo cavallo incedente verso d.[estra] b) Gruppo in tutto simile, c) Figura muliebre velata, rivolta verso i Dioscuri, ossia verso sin.[istra] Reca nelle mani l'orciuolo e la patera, e sembra offrire la libazione agli eroi, d) Figura di giovinetto ammantato, rivolto c. s. [come sopra; note 46] e) Figura di vecchio barbato, con palma nella d.[estra] rivolto c. s. [come sopra] f) Figura di donzella velata. La corrosione del marmo vieta di distinguere l'oggetto, che solleva in alto con la destra; rivolta c. s. [come sopra] g) Figura di fanciulletto, anch'esso ammantato [note 47]. Due colonne grezze di bigio, lunghe ciascuna m. 2,90. Testa colossale, non saprei dire se di donna, ovvero d'un Bacco o d'un Apollo. Avea la vitta riportata di bronzo. Oltre a cento frammenti di scolture figurate, da ricomporsi. Frammenti di colonne e cornici in breccie orientali [my emphasis]".

Why I identified Lanciani's (NSc 1885, 423): "Testa colossale, non saprei dire se di donna, ovvero d'un Bacco o d'un Apollo", with the head of Livia in Budapest (Fig. 5).

The reason to suggest this hypothesis was the Dioscuri relief in the Museo Nazionale Romano, which can be identified on the basis of Lanciani's (NSc 1885, 423) excavation note, and of which we learned above, in Section II., that it had obviously been the property of Mrs. Field immediately after its excavation [in the Domus 55a-d here Fig. 2, together with the head of Livia; Fig. 5] - on the basis of the special agreement negotiated by her with the city of Rome.

My colleague, the archaeologist Hans Rupprecht Goette, with whom I have been discussing this portrait of Livia (Fig. 5) for decades, informed me in July 2021 about his new research results, which he had just achieved with Árpad M. Nagy concerning this sculpture. On this occasion, Hans Goette also asked me about the find spot of this Livia portrait in Budapest, which I state in my dissertation: because he and Nagy did not find my identification of Lanciani's description of the find of a colossal head (NSc 1885, 423) with the portrait of Livia (Fig. 5) convincing. I took this opportunity to explain the reasons for this identification in the necessary detail [by writing an additional chapter; note 48]; I have, of course, made this chapter available to both gentlemen. In this text, however, neither the corresponding passage from the first, typewritten version of my dissertation (1986) is quoted verbatim, nor the relevant passage from the printed second version of my dissertation (1991), which I will do below.

Compare Häuber 1986 [note 49]: Following the verbatim quotation from Lanciani (NSc 1885, 423), I have identified the Dioscuri relief described in the text with the one in the Museo Nazionale Romano [with note]: "MNR I,8 II (1985) No. XI,6", and put forward the following hypothesis regarding Lanciani's `colossal head´:

"[translated from the German:] [a] Since the Dioscuri relief was only recently acquired from the Brancaccio family [in 1970; cf. supra, in Section II.], it seems plausible to assume that the colossal head also belonged to the Brancaccio family. For this reason and because of [Lanciani's] description, I suggest the identification with a head in Budapest: Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts, Inv . No. 4134. Cat. [page 29] Hekler (1929) No. 115 ``from Palazzo Field-Brancaccio in Rome´´. [b] According to an idea of D. Salzmann, this piece is a bust of Domitian as Apollo - the wreath made of two parts was worked separately and attached to the temples - which was later reworked into a Trajanic female portrait, see the reworking at the neck for the hair bun. I. Carradice was kind enough to send me photos of coins of Domitian as Apollo [see illustration volume, p. 99; Häuber photo archive], which are in the British Museum [note 50]. One can therefore only admire Lanciani's above-quoted description of the bust in the NSc [my emphasis]".

Regarding the argument marked [a] in this text, we can, based on what was said above in Section II., assume with certainty that this `colossal head´ described by Lanciani (NSc 1885, 423), as well as the Dioscuri relief excavated with it, and the fragments of the Torello Brancaccio (Fig. 4) from the same site, was the property of Mrs. Field immediately after its excavation, and was initially located in the Pre-Palazzo Brancaccio (here Fig. 2, label: "48 P.[re-Palazzo Brancaccio]"; and below, note 77), later in the Palazzo Field, and still later in the Palazzo Field-Brancaccio (the present Palazzo Brancaccio).

Later, in 1998 (see below), I have corrected the interpretation of this head in Budapest (Fig. 5) marked [b] in the text, quoted above. In the second, printed version of my dissertation (1991) [note 51], I unfortunately omitted the argument marked above [a] and retained only my interpretation [ b]:

"[translated from the German:] 6. Bust of Domitian as Apollo, later reworked into a Trajanic female portrait. Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts [page 317] Inv . No. 4134; Cat. Hekler (1929) No. 115: ``from Palazzo Field-Brancaccio in Rome´´. Findspot: see NSc 1885, 423 (H 8). I owe the interpretation of this find to D. Salzmann. According to him, Domitian was depicted as Apollo. The wreath was made separately from two pieces and attached to the temples. The reworking at the neck stems from the fact that the hair bun of the female portrait was later attached there. I. Carradice was kind enough to provide me with photos of coins of Domitian as Apollo, which are in the British Museum. If my identification of Lanciani's excavation note in the NSc with this portrait is correct one can only admire his description: "Testa colossale, non saprei dire se di donna, ovvero d'un Bacco o d'un Apollo. Avea la vitta riportata di bronzo" (see NSc 1885, 423 [my emphasis])".

Why I have followed in 1998 Hans Goette's suggestion that the portrait (Fig. 5) depicts Livia [note 52]:

``[translated from the German:] This head (here Fig. 5) depicts Livia, the wife of Octavian/Augustus, and is now in Budapest, in the Museum of Fine Arts (inv. no. 4134). Over time, it has been identified as a portrait of various women, but also as a portrait of Domitian [with note 199]´´.

In my note 199, I write :

``[translated from the German:] For the portrait of Livia in Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts (inv. no. 4134) [= here Fig. 5], compare R.C. HÄUBER 1991, 316-317, cat. no. 6: "[translated from the German:] Bust of Domitian as Apollo, later reworked into a Trajanic female portrait". I have corrected the identification proposed here in my essay of 1998, 199-100, 110 with note 148, Fig. 12,1-4: "Possibly Livia posthumously as diva".

Compare C. HÄUBER 1998, 110: "[translated from the German:] From this area comes ... a larger-than-life portrait, possibly depicting Livia (Fig. 12 [= here Fig. 5]) [with note 148]".

In my note 148, I write: "[translated from the German:] or Antonia (because of the facial features, compare HEKLER), posthumously identified as diva due to her height. The mass of hair above the ears speaks against the identification as Domitian. These observations were kindly shared with me by Hans Rupprecht Goette, who is working on the piece. The hairstyle, with a center parting and (formerly attached) bun at the neck, combines features of various Livia portraits, compare FITTSCHEN-ZANKER III,1 [1985] (on bun at the neck); p. 4 (on center parting) (ZANKER), compare D.E.E. KLEINER, Roman Sculpture, Yale University Press 1992, p. 77, fig. 56 (Livia as Venus, turquoise cameo Marlborough); see A. HEKLER, Museum der bildenden Künste in Budapest, Vienna 1929 , cat. no. 115 (portrait of a woman of the gens Claudia); HÄUBER 1991, p. 316f., no. 6 (Domitian); NSc 1885, p. 423 (findspot: Via Buonarroti); D. KREIKENBOM, Griechische und Römische Kolossalporträts, JdI, 27. Ergh, 1992, p. 107f., pl. 35 (Domitian)".

Compare C. HÄUBER 2014, 202 with note 49 (with the older literature ... "On December 12th, 2012, Hans Rupprecht Goette, who is in the course of writing a catalogue of the Museum together with Arpad Nagy, was so kind as to write me: ``[translated from the German:] Arpad Nagy and I have ... written a text about the portrait (we consider it to be a Hellenistic portrait head that was [probably] reworked into a Livia´´"), p. 813, Fig. 131 [= here Fig. 5].

The four photographs of the Livia portrait, shown here as Fig. 5, were kindly sent to me by Árpad M. Nagy of the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest in 1985. With his kind permission, I was able to publish them for the first time in my 1998 essay. Because this is such an exceptional piece among the Esquiline finds, I contacted Árpad M. Nagy again in connection with my [Laocoon-] lecture on January 7, 2019, because I wanted to depict this portrait from all angles in the publication already planned at the time and now presented here. I am very grateful to Mr. Nagy for giving me this permission again in writing in 2019 ... [my emphasis]´´.

Hans Rupprecht Goette and Árpád Miklós Nagy [note 53] now write the following about this Livia portrait (here Fig. 5) in Volume I of the new catalogue of the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest [translated from the German]:

``73 Portrait of a Ptolemaic queen, reworked as a portrait of Livia, pls. 124-131

Inv. 4134, dimensions: H. 47 cm; H. chin-parting: 33.4 cm ... Material: medium-crystalline, white marble (Paros-Marathi [Lychnites]) ... Provenance: according to P. Arndt from the Palazzo Field-Brancaccio in Rome; acquired through Arndt in 1912 ... If the head is identical with the fragments mentioned by R. Lanciani, NSc 1885, 423 [with note 3] (so Häuber 2022 [= HÄUBER, Laokoon]), then it would have been found at that site together with other sculptures, including the so-called Esquiline Group in Copenhagen (see note 1) and also the Eudoxos relief (here cat. 80, 4778).

Date: 3rd century BC / Augustan period [my emphasis]´´.

The above-quoted catalogue text by Goette and Nagy (2024, 147, at cat. no 73) contains some errors:

a) "[translated from the German:] If the head is identical with the fragments mentioned by R. Lanciani, NSc 1885, 423 [with note 3] (so Häuber 2022 [= HÄUBER, Laokoon]) ... [my emphasis]".

But since Lanciani (NSc 1885, 423) meant this head with his "testa colossale", it would have been correct to write instead: "If the head is identical with the one mentioned by R. Lanciani, NSc 1885, 423, together with ancient fragments" - but see below, note 3 by Goette and Nagy;

b) "[translated from the German:] ... then it would have been found at that site together with other sculptures, including the so-called Esquiline Group in Copenhagen ... [my emphasis]" .

Instead, it is correct that this `colossal head´, mentioned by R. Lanciani (NSc 1885, 423), was discovered together with only 3 plinths of the `Esquiline Group´ [note 54]; most of the other fragments of the `Esquiline Group´ (which belonged to at least 18 larger-than-life statues, of which only 5 could be partially restored) were instead discovered in ancient `statue walls´ [note 55] `opposite´ the Domus 55a-d, from which the Livia head [Fig. 5] comes, during the construction of the 4 new buildings of the Convent of the Suore di S. Giuseppe di Cluny No. 54 I.-V. Convent S. Giuseppe (Fig. 2).

Goette and Nagy (2024, 147, note 3), after quoting Lanciani, NSc 1885, 423 verbatim, write:

"[translated from the German] The fact that Lanciani considered an interpretation of the fragments as a representation of Dionysus or Apollo hardly allows, in our opinion, the identification of that find with the head in Budapest, as considered by Häuber 2022 [= HÄUBER, Laokoon], because neither the portrait hairstyle nor the individual facial features would have led the experienced researcher [i.e., Lanciani] to such a formulation [my emphasis]".

c) Lanciani (NSc 1885, 423) obviously does not speak of 'Dionysus or Apollo', as Goette and Nagy (2024, 147, note 3) claim, but of 'Bacco and Apollo'. It is also again incorrect that Goette and Nagy (op.cit.) do not speak of 'the colossal head', as Lanciani (NSc 1885, 423) writes, but of (its) fragments, because they obviously assume that this Livia head must have been found in fragments.

Hans Goette and I had already discussed this problem many years ago. At the time, I tried to explain to him that in these excavation reports (after 1870), it was demonstrably very often the already restored sculptures that were described and measured (I will return to this below).

Since Goette and Nagy (2024, 147, note 3) do not write "testa colossale" here, as Lanciani ( NSc 1885, 423), but rather "fragments", they also admit - without reflecting - that my identification of this excavation note by Lanciani with the Livia head in Budapest (Fig. 5) is correct, because this larger-than-life head of Livia actually consists of numerous fragments.

d) Goette and Nagy (2024, 147, note 3) do not mention that Dieter Salzmann interpreted this head of Livia as a portrait of Domitian - an interpretation that Dieter Salzmann had kindly suggested to me personally and which I followed in the first version of my dissertation (1986; quoted above); as well as in the second version of my dissertation (1991; quoted above), which Goette and Nagy also mention in their bibliography on this Livia portrait.

As is well known, Detlev Kreikenbom (1992) also identified this head of Livia as Domitian (see above, text to note 52, the quotation from HÄUBER, Laokoon, note 199); Goette and Nagy (op. cit.) also cite Kreikenbom (1992) in this bibliography.

I am glad that I initially thought that the Livia head [here Fig. 5] was a portrait of Domitian, reworked as a female portrait – in which I followed Dieter Salzmann; Detlev Kreikenbom also identified this head with Domitian – because this error shows that this head has something 'ambivalent' about it.

As announced above, we now turn to the fact that in the excavation reports (after 1870) some new finds were only described and measured after restoration had taken place.

In the following I cite two examples from my dissertation: The first example is the largest marble candelabrum found (after 1870), the second is a statue of Venus [note 56].

Compare page 21:

"[translated from the German] The presentation of the statues [in the "Sala ottagona"] with plaster additions (modeled on the fractures), which had been considered appropriate (because `unsupplemented´) by Lanciani's generation, is openly criticized in Stuart Jones's [1926] catalogue, and it is praised that they had since been removed (in 1925-26) (with note 81).

One could call it an irony of fate that it is precisely the illustrations in this catalogue [STUART JONES 1926] that have made famous those statues with the additions created for their installation in the "Sala ottagona" - even though they no longer looked like this by the time the catalogue was published (1926). These photographs with the additions are also indispensable for determining the provenance of some sculptures, since in the Elenchi of the BullCom, they are described and measured with those plaster additions (see note 82 [my emphasis]).

Compare note 82 [translated from the German]: "e.g. [for example] cat. 196, see p. 118, Sala ottagona 152.

Compare p. 118, Sala ottagona: "152. Marble candelabrum - Cat. 196

Inv. No.: MC 1115

Stuart Jones, Pal.Cons., Ort.Lam. 24 p. 143 plate 51.

H. 2.10 m

Provenance not specified.

In my opinion identifiable with BullCom 5, 1877, 270 No. 2 ... Cain [H.-U. CAIN, Römische Marmorkandelaber, 1985] 176f. Cat. 77 p. 2 note 6 p.12 note 70 pp. 93, 96f. 130. 142 pl. 55, 3f.; 57,3; 83,3f.; 87; Appendix 9.12.13.

[This is: p. 282, cat. [translated from the German:] "The Statues from the Horti of Maecenas; The New Finds (after 1870)", no. 196.]

Page 282: "196. Marble candelabrum

Stuart Jones, Pal.Cons., Ort.Lam. 24 ...

Findspot of the candelabrum shaft: April 30, 1874 Picchetto L 5 (F 11)

Height: 0.70 m; diameter: 0.30 m

RT III, 362, see Häuber, in: Cat. Horti Lamiani [= HÄUBER 1986] 179 with note 56 Fig. 114 (= Moscioni 4374, detail, taken in the "Sala ottagona").

Findspot of the candelabrum base: 17.4.1875 Picchetto I 0 (Via Giovanni Giolitti, corner of Via Mamiani. Given the great distance between the two sites, it is of course questionable whether the two parts belong together, so also Cain [1985] (op.cit.; my emphasis)".

Compare p. 65 [translated from the German]:

"No. 18, Parker Catalogue 45

Statue of Venus in fragments, type similar to the Aphrodite of Syracuse - Cat. 241

[Musei Capitolini] Inv. No.: MC 957, Galleria di Congiunzione

Stuart Jones, Pal.Cons., Galleria 6; p. 79 plate 30.

H (without the plinth): 1.17m

Findspot: 1874 private baths Via Ariosto (H 10).

BullCom 1, 1872-73, 290 No. 14 (the statue compared there is Amelung, Vat.Cat. II No. 441; Pl. 75; Bieber, Ancient Copies, 1977, Ill. 233ff.); 3,1875, 80. The note in BullCom 1 is one example of many that the statues were described in the Elenchi after they had already been restored, here: "... in atto di profumarsi", compare the Parker photograph [see p. 60: it is Photo Parker 3234; cf. HÄUBER 1986, p. 183, Fig. 118; HÄUBER 2014, p. 192, Fig. 53] with the illustration in Stuart Jones [my emphasis]".

The head of Livia in Budapest (Fig. 5) was, in my opinion, described and measured by Lanciani (NSc 1885, 423) only after its restoration. Because of the above-mentioned discussion with Hans Rupprecht Goette about this head of Livia, I will now improve my 'Topographical Manifesto' accordingly. In its current version, it states [note 57]:

"[translated from the German:] The following addresses some of the difficulties that can turn up in `archaeological urban research´, when investigating details. These 17 points of a 'Topographical Manifesto - not only valid for Rome' are based on numerous research examples (cf. C. Häuber and FX Schütz 2004, 109; C. Häuber 2005; Ead. in preparation for printing [= HÄUBER 2014]) ...

6. Many find reports from earlier centuries are at first glance incomprehensible ...

8. For the period of major construction projects in Rome (from approximately 1870 to 1911), there are numerous published excavation reports without photographic documentation. For those finds from this period whose origins have not been adequately documented, it is difficult today to reconstruct their provenance ...

10. The published excavation reports mentioned under 8. may contain information on the geographical location of finds, distances, periods and dimensions (of buildings and finds) that are difficult to understand from today's perspective [my emphasis]".

I will now expand point 10 of my ‘Topographical Manifesto’ (2013, 151) as follows:

"10. The published excavation reports mentioned under 8. may contain information on the geographical location of finds, distances, periods and measurements (of buildings and finds) that are difficult to understand from today's perspective. In the case of the finds, this may be due, among other things, to the fact that they were only described and measured after their restoration [my emphasis]".

In contrast to Hans Rupprecht Goette and Árpád Miklós Nagy (2024, 147, note 3), I maintain my identification (from 1986 to HÄUBER, Laokoon) of Lanciani's excavation note (NSc 1885, 423) with this larger-than-life head of Livia in Budapest (Fig. 5), for the following reasons [note 58]:

1.) Legal situation. As shown above in Section II., Lanciani's (NSc 1885, 423) 'colossal head' must have been the property of Mrs. Field immediately after its excavation in the Augustan Domus 55a-d (Fig. 2) on Via Angelo Poliziano, on a plot of land that had previously belonged to her - due to the special conditions granted her by the City of Rome. This head will, therefore, have been kept initially in the Pre-Palazzo Brancaccio (see below, note 77), later in the Palazzo Field, later called Field-Brancaccio (and today Palazzo Brancaccio; compare Fig. 2); where it is already attested before its purchase by the Budapest Museum in 1912 [note 59].

2.) The Field-Brancaccio Collection of antiquities. A survey of all antiquities (formerly) owned by the family Field-Brancaccio has shown that Lanciani's 'colossal head' is neither in the Palazzo Brancaccio nor in the Parco Brancaccio (here Fig. 2) [note 60].

3.) Purchase of the head of Livia `1912 from the Palazzo Field-Brancaccio´ [note 61], which Mrs. Field had built as "Palazzo Field" [note 62]; the Palazzo Field (today: Brancaccio) was built according to Luca Carimini's plans of 1886.

4.) The characteristics of the portrait of Livia. Apart from the results of the research mentioned under 2.) and the fact that the Livia head originally belonged to Mrs. Field (see points 1.) and 3.) above), two further peculiarities are sufficient to identify it with Lanciani's (NSc 1885, 423) `colossal head´: its larger than life format, and the traces of former attachments to its temples, or, as Lanciani (NSc 1885, 423) wrote: "Avea la vitta riportata di bronzo" [note 63].

However, there are still a few questions open regarding the portrait of Livia in Budapest (Fig. 5), which I have summarized in:

'IV.2.6. Conclusion of the chapter on the installation of the Laocoon group´ [note 64].

Below I quote a greatly abridged passage from this chapter:

"[translated from the German:] This installation by Maecenas in his Horti consisted - according to my hypothesis - just as in the case of the (presumed royal Ptolemaic models) in setting up marble statue(s?) against the background of richly incrusted walls, in addition to a richly decorated floor (which can also be assumed for the Ptolemaic models). In my opinion, the subject chosen by Maecenas for the sculpture, `Death of Laocoon´, cannot be explained at all except with reference to Octavian/ Augustus; cf. HÄUBER (2021/2023, p. 694).

However, we cannot know whether this installation originally included more statues than the Laocoon group. If the scenario developed here were true, one could assume that the sculptures contained portrait statues of Augustus and his family - assuming that Ptolemaic models such as the Thalamegos were indeed intended to be imitated (cf. PFROMMER 2002, pp. 93-98, who has reconstructed the Thalamegos; HÄUBER 2014, pp. 611 ff., especially pp. 618 with notes 68, 74, p. 805 with note 21). The `mythical ancestor Laocoon´ [i.e., of Augustus, the descendant of the Trojan Aeneas, the son of Aphrodite and Anchises - the brother of Laocoon] could have replaced the `divine ancestors´ of the Ptolemaic royal family in the sculptural group on the Thalamegos.

A portrait of Livia in Budapest (here Fig. 5) from the same site as the Laocoon group:

In this context, it may be of interest that, in my opinion, the larger-than-life portrait of Livia in Budapest comes from the same site as the Laocoon group (Fig. 5) ...

What was the function of this Livia portrait? Several peculiarities of this portrait, however, seem to rule out its connection with the Laocoon group, as cautiously considered here:

First, the larger-than-life proportions of the portrait, which, since Livia is actually depicted, would probably have only been possible after Livia's death - but she only died in 29 AD; compare Häuber (2017, 529 with note 249). However, it is well known that her son, the Emperor Tiberius, had not divinized Livia immediately after her death - her divinization was only initiated by her grandson, the Emperor Claudius; compare Nicholas Purcell ("Livia (RE `Livius´ 27) Drusilla", in: OCD3 [1996] 876); POLLINI 2012, p. 335 with note 119.

If, therefore, this portrait, because of its larger-than-life proportions, really represents "Livia, posthumously as diva", as I have suggested (1998 [cf. supra, text related to note 52]), then it cannot possibly have been commissioned by Maecenas himself (Maecenas died already in 8 BC; see above, Chapters III.3. ; III.3.9.).

The presence of its many (former) attachments may also speak against the possibility that this portrait of Livia, together with the Laocoon group, could have belonged to an ensemble similar to that on the Thalamegos of Ptolemy IV (see above, Chapters IV.2.4 .; IV.2.4.1.) ...

In addition, as observed by Hans Rupprecht Goette and Árpad M. Nagy (see above, note 199 [see above, text related to note 52; compare now GOETTE and NAGY 2024, p. 147, cat. 73]), the portrait (here, Fig. 5) was, in their opinion, reworked from a Hellenistic portrait. The additions would then have already distinguished the Hellenistic `original´, which is, for example, typical of Ptolemaic portraits ...

There's another consideration, though I'm unfortunately unable to judge the possible consequences myself: If this portrait of Livia had already been reworked from a Hellenistic original, then this would naturally already have had this `supernatural´ size. Would it have been permissible in such a case to portray Livia larger than life during her lifetime (and during Maecenas's lifetime) - precisely because a suitable head was available, into which one only needed to `inscribe´ Livia's facial and other features, but which `just happened´ to possess these proportions?

In my opinion, the Augustan Domus 55a-d (here Fig. 2), where the head of Livia (Fig. 5) and the Laocoon group were found, stood in the `private´ part of the Horti of Maecenas. Pliny (Nat. Hist. 36, 37-38) famously stated that the Laocoon group was - undeservedly, in his opinion - completely unknown. This could be explained, for example, by the fact that this part of the Horti of Maecenas, where the Laocoon group was accidentally rediscovered in 1506, was quite `remote´ within these Horti (intentionally, as I believe; see below, Chapters IV.2.7.; IV.2.8.).

Personally, I have no idea how the `multi-layered´ characteristics of this portrait of Livia (here Fig. 5), described above, could be explained, and I am curious to see at what conclusion Hans Rupprecht Goette and Árpad M. Nagy themselves will reach in their catalogue, who, moreover, know the piece from autopsy".

The passage just quoted was written a long time ago, when on June 13, 2025, I found in John Pollini's book (2012) that in various places of the Roman Empire, private individuals had already worshipped Augustus `inofficially´ during his lifetime, for example a certain P. Perelius Hedulus, who built a private temple of the Gens Augusta (cf. ibid. 2012, pp. 88-89, with note 104). Therefore, on June 14, 2025, I decided to quote in the following the final remarks of Chapter IV.2.6., Punkt 14.), in which I, concerning Maecenas, have come to exactly the same conclusion. I then called Eberhard Thomas on the same day, whom I thank for discussing with me the ideas developed here regarding the portrait of Livia (here Fig. 5):

"[translated from the German:] By judging from the wall decoration of this room, in which the Laocoon group was found, Maecenas's installation of the Laocoon group - provided, he had commissioned it at all - possibly imitated royal Ptolemaic models, such as the grotto on the Thalamegos of Ptolemy IV. Compare for a very similar wall decoration, found in a secondary context, here 53. Slide. Wall decoration of gilded copper tendrils, in which (semi-)precious stones were set. From the Horti of Maecenas on the Esquiline, Via Machiavelli. From: M. Cima (1986, 116, Tav. 29; 30); C. Häuber 2014, 830, Fig. 154). Furthermore, this installation - with the Laocoon group - possibly even included an homage to the `mythical ancestors´ of his friend Octavian/ Augustus, thus another special feature that may also have been copied after Ptolemaic models, such as the statue group of the royal family in the Thalamegos Grotto, which was also presented `in the midst of their mythical ancestors' (see above, Chapters IV.2.4; IV.2.4.1.). I imagine that Maecenas also commissioned for this room [where the Laocoon group was on display] portraits of his friend Octavian/Augustus and his family - for example, of his wife Livia (here Fig. 5).

Maecenas seems to have realized in his Horti something like an `imperial cult´, and that a) although his Horti were not located somewhere in the Roman provinces or in distant Greece, but in the heart of Rome; and that, in addition to this, b) already during Octavian/Augustus's lifetime (!) - avant la lettre, of course, as so often with his innovative ideas. For Maecenas's innovative ideas, see HÄUBER (2014, 616, with notes 50-52, Figs. 98; 81).

To my great surprise, Goette and Nagy, in their catalogue text of this portrait of Livia (Fig. 5), do not address the problem I mentioned above, namely that this portrait, whose reworking into Livia they date `Augustan´, under `normal circumstances´, could not possibly have depicted Livia already in the Augustan period - because of its larger-than-life proportions.

Compare Goette and Nagy on the Livia portrait (Fig. 5) [note 65]:

"[translated from the German:] If the considerations presented here are correct, the heavily fragmented, larger-than-life head [here Fig. 5] represents the portrait of a Ptolemaic queen, transferred to Rome in antiquity (from Alexandria?), which was reworked in the Augustan period into that of the Empress Livia [with note 8: With bibliographical references and further discussion]. Given the chain of evidence that it was once owned by the family Field-Brancaccio, that ancient sculptures from excavations on the grounds of their palazzo were restored and preserved there, and that the latter, in turn, covered parts of the ancient villa of Maecenas, one may conclude that the once impressive, representative work [here Fig. 5] belonged to the sculptural decoration of that Esquiline area [my emphasis]".

IV. Theatrical talent and passion for theatre as a `family characteristic´ [note 66]

Years ago, Gabriella Centi generously presented me with three books that came just in time as I wrote the following text. They are two books by Bianca Ceccarelli, the older sister of Principessa Fernanda Ceccarelli Brancaccio: one is about her father, the famous anarchist Aristide Ceccarelli (Mio padre, l'anarchico, 1984). The other, written by Bianca Ceccarelli (her stage name was: Bianca Star), is about her career as a singer, silent film- and variety star: Bianca Star (I miei Anni Venti, 1981). The third book is dedicated to the stage successes of Rolando (Roland) Brancaccio, the great-grandson of the builder of the Palazzo Field (now Brancaccio), Mrs. Field: Roland Brancaccio (La carriera artistica di Roland Brancaccio attraverso i giudizi della critica, 1976).

Both T.P. Wiseman and Filippo Coarelli [note 67] point out that Maecenas either maintained a theater in his Horti, as Wiseman believes, or, as Coarelli suggests, offered theatrical performances to his friends invited to banquets in the `Auditorium of Maecenas´ (Fig. 2). Added to this is the fact, previously unknown to me at least, that Peter Wiseman [note 68] tells us:

Terentia, Maecenas' wife, was a dancer. Maecenas's passion for the theater was thus a ´family trait´. The same can now be said of the family Field-Brancaccio.

The members of the Field-Brancaccio family are known for their significant patronage [note 69).

Judging by the contemporary sources which report on their financial situation, one would nowadays describe Mrs. Mary Elizabeth Bradhurst Field and her husband as billionaires [note 70]. Mrs. Field (New York City 1824-18.2.1897 Rome) had acquired very extensive land holdings on the Esquiline in order to build her Palazzo Field (now Brancaccio) with a large park on the west side of the modern Via Merulana, in which she lived from then on, together with her husband, Mr. Hickson Woolman Field Jr., her daughter and her husband, and with their three children: Principe Salvatore Brancaccio, Principessa Mary Elizabeth Brancaccio (14.4.1846-11.4. 1909) [note 71], and their children Carlo, Marcantonio and Maria Eleonora Brancaccio. At the time of its greatest extent, the former property of Mrs. Field behind the Palazzo Field (now Brancaccio) included what is now Parco Brancaccio, which, then called 'Villa Brancaccio', extended westwards almost to the Colosseum, and southwards to the modern Via Labicana.

In order to get an idea of the size of these lands formerly belonging to Mrs. Field - the 'Villa Brancaccio' - behind the Palazzo Field (now Brancaccio) on the Mons Oppius, it is advisable to consult our diachronic map of Rome, of which Fig. 2 shows a detail :

<https://FORTVNA-research.org/maps/HAEUBER_2022_map3_Forum_Romanum-Oppius.html>,

labels: MONS OPPIUS; COLOSSEUM; modern Via Labicana; Baths of TITUS; Parco di Traiano; Baths of Trajan; "Sette Sale"; DOMUS AUREA; Parco del Colle Oppio. If one visits these two now public parks, whose grounds belonged to the properties acquired by Mrs. Field on the Mons Oppius, one will search in vain for an honorary inscription or even a statue in honor of Mrs. Field. It was undoubtedly Mrs. Field's merit, thanks to her painstaking acquisition of these extensive properties, that these important ancient buildings located here were protected from development, and, in addition, that these two extensive parks could later be created for the people of Rome. Compare what I wrote about this in 2014 [note 72]:

"Alberta Campitelli mentions the fact that in 1912 the Mayor of Rome, Ernesto Nathan, had commissioned ``una proposta di vincolo per le ville di importanza storica e artistica´´, among which was ``Villa Brancaccio´´, but instead of being protected this property was among those which ``hanno ceduto all'edificazione parte dei loro parchi e giardini´´ [with note 219] ...

It was obviously Mrs. Field (and her husband? [with note 220]), who by building her Palazzo and park and pursuing very different goals, unconsciously `saved' a large area on the Oppian, where important ancient buildings `survived', thus later enabling the Comune di Roma to create two large public parks in this area [with note 221; my emphasis]".

Compare my note 219: "A. Campitelli, in Ead. 1994, p. 10".

Compare my note 220: "So [in my opinion erroneously, Peter] Rockwell 2005 [in: C. HUEMER 2005a], pp. 6, 7".

Compare my note 221: "Mrs. Mary Elizabeth Field as owner of Palazzo Field-Brancaccio and of the `Villa Brancaccio´ is mentioned by Campitelli, in Ead. 1994, p. 83 (but she confuses her with her daughter, Principessa Mary Elizabeth Brancaccio). For Mrs. Mary Elizabeth Bradhurst Field, cf. Centi 1982; Ead. 1997, both passim; and Häuber, and Schütz 2004, pp. 70-71, 84, 86-90".

Gabriella Centi and I have both documented the acquisition of these lands on the Mons Oppius by Mrs. Field (from 1872-1879 or until around 1882?) using archival material, as well as the expropriation in 1935 of parts of the `Villa Brancaccio´ by the Comune di Roma (today Roma Capitale) [note 73].

Thus, Rodolfo Lanciani (1885), who (as we have already heard above, in Section II.), was a regular guest in the salons of Principessa Brancaccio in the Pre-Palazzo Brancaccio (see below) and later in the Palazzo Field (now Brancaccio), reported that Mrs. Field, `about three years ago´ [note 74], had acquired the huge vineyard of the Church of San Pietro in Vincoli; compare our Map 18 of the Horti of Maecenas, showing the vineyards on the Mons Oppius, as documented on G.B. Nolli's Large Rome Map (1748) [cf. HÄUBER 2014, p. 882, the key to "Map 18"];

compare: <https://FORTVNA-research.org/horti/hm_map10.jpg>,

label: Vigna de' Canonici Reg. di S. Pietro in Vincoli.

Incidentally, Mrs. Field had literally built her Palazzo Field (now Brancaccio) `on´ the (main) Domus/ the `Palace´ in the Horti of Maecenas (here Fig. 2). This family not only shares Maecenas's patronage of the arts, but also the `theatrical talent and passion for the theater´ of Maecenas an his wife Terentia, both of which were also a `family hallmark´ in the case of the family Field-Brancaccio.

One might ask whether Mrs. Field's daughter, Principessa Mary Elizabeth Brancaccio, should not already be credited with a `theatrical´ talent for her highly successful `staged´ garden parties and salons in the state rooms of the "Pre-Palazzo Brancaccio" and in the park behind it - as I personally believe. The design of the festive `setting´ for these receptions, namely the palazzo itself, was largely her own personal responsibility; Francesco Gai actively and competently supported her in the design of the palazzo [note 75].

For example, on 22 May 1886, Principessa Elizabeth Brancaccio invited people to a garden party, which was attended by none other than King Umberto I and Queen Margherita, whose lady-in-waiting Principessa Brancaccio was [note 76].

The guests were led into the park next to the Coffee House and into the reception rooms of the `Pre-Palazzo Brancaccio´ (which were later integrated into the Palazzo Field-Brancaccio); Fig. 2, compare: https://FORTVNA-research.org/maps/HAEUBER_2022_map3_Forum_Romanum-Oppius.html, labels: 48 P.[re-Palazzo Brancaccio; note 77]; Palazzo Brancaccio; Parco Brancaccio; Coffee House; VI. 358 [= its number in the `Catasto Pio Gregoriano´, 1866] Casina Gai / TURRIS: MAECENAS; COLOSSEUM; Baths of Trajan.

The group of guests, including the royal couple and the family Field-Brancaccio, who were seated under tall palm trees at the Coffee House in what is now the Parco Brancaccio, or standing and chatting in groups, with the Colosseum in the far distance and the nearby ruins of the Baths of Trajan, were depicted by Francesco Gai in a colossal painting (measuring 600 x 950 cm). It featured 21 life-size portraits, which could easily be realized in the studio of the Casina Gai, which had sufficient height [note 78].

Even if one does not want to grant Principessa Elizabeth Brancaccio, due to her `events´, a corresponding `theatrical´ talent, the `theatrical talent and passion for the theatre of the family Field-Brancaccio´ became evident at the latest with her two sons, Carlo Brancaccio (29.12.1870-1.1.1916) and Marcantonio Brancaccio (29.5.1879-5.11.1961).

Their grandmother, Mrs. Field, had left to them her Palazzo Field in equal shares [note 79]. In 1914, the two brothers added a fourth floor to the palazzo and built the Teatro Morgana (later Cinema Brancaccio, now the Teatro Brancaccio) within what is now Parco Brancaccio (Fig. 2). Rolando (Roland) Brancaccio, the son of the older brother, Carlo Brancaccio, would later become an internationally acclaimed stage star [note 80].

Marcantonio Brancaccio, the younger brother, was closely associated with a famous stage- and silent film star, the singer and variety artist Bianca Star [note 81]. Bianca Star's real name was Bianca Ceccarelli (1898-17.11.1985). Her father was the important anarchist Aristide Ceccarelli (27.3.1872-5.8.1919) [note 82]. On 1 April 1959, at the age of (almost) 80, Principe Marcantonio Brancaccio married Bianca Ceccarelli's younger sister, Fernanda Ceccarelli (7.7.1907-22.10.2014) 83 . Why am I mentioning this marriage here?

Because throughout his life, [the later] Principe Marcantonio Brancaccio continued the fine tradition of his grandparents (Mr. and Mrs. Field) and his parents (Principe Salvatore and Principessa Mary Elizabeth Brancaccio) of being extremely open to the research of archaeologists and art historians. We have already seen this in the case of Marcantonio Brancaccio's grandparents and parents (see above, in Section II.), as well as in his own case [note 84]. For example, in 1905, Marcantonio Brancaccio invited the archaeologist Giovanni Pinza to study and publish ancient finds from the Esquiline necropolis in his collection, which had been discovered in the excavation site of Palazzo Field (later Brancaccio); later, he repeatedly invited archaeologists to carry out scientific excavations in the park belonging to Palazzo Brancaccio. As we learn from Emanuele Gatti (1983a), Carlo and Marcantonio Brancaccio had arranged for a scientific excavation for the site within today's Parco Brancaccio, before their Teatro Morgana/Brancaccio was built in 1914.

And because, fortunately for all archaeologists interested in the Horti of Maecenas, and for all art historians interested in the Palazzo Brancaccio and its important art treasures, Principe Marcantonio Brancaccio's wife, Principessa Fernanda Ceccarelli Brancaccio, continued this extremely generous policy of her husband and his family until the end of her life (2014). I have also personally benefited greatly from this since 1981; most recently, in 2013, she kindly granted me the permission to publish ancient architectural fragments from her collection [note 85].

It is, therefore, no exaggeration to say that research on the Horti of Maecenas and on the Palazzo Brancaccio and its art and jewelry collections experienced a `golden age´ under the future Principe Marcantonio Brancaccio and his wife, Principessa Fernanda Ceccarelli Brancaccio, over the very long period from 1905 to 2014. Now, after the death of Principessa Fernanda Ceccarelli Brancaccio, such research is no longer possible due to inheritance disputes [note 86].

Cited literature:

HÄUBER, Laokoon

HÄUBER, C., Die Laokoongruppe im Vatikan - drei Männer und zwei Schlangen: `Ich weiß gar nicht, warum die sich so aufregen´ (Wolfgang Böhme). Die Bestätigung von F. Magis Restaurierung der Gruppe und der Behauptungen, sie sei für die Horti des Maecenas, später domus Titi, geschaffen, und dort entdeckt worden, FORTVNA PAPERS vol. IV (in Druckvorbereitung).

The bibliography accompanying this book, from which numerous publications are cited in the text presented here, is published online.

Compare <https://FORTVNA-research.org/FORTVNA/FP4/Literatur.html>.

Footnotes:

1. HÄUBER 2021/2023, p. 9, also on the magnificent offer made to me by Demetrios Michaelides; compare HÄUBER 1991, p. 1; HÄUBER 2014, pp. XV-XVIII, with notes 14, 15, p. XXI with note 28; most detailed in: HÄUBER 2024, also on Eugenio La Rocca, Amanda Claridge, Filippo Coarelli, T.P. Wiseman, and Lucos Cozza.

2. On STUART JONES: WALLACE HADRILL 2001, pp. 27-28. On the fact that STUART JONES (1926) and MUSTILLI (1939) did not themselves clarify the provenances of the new finds (after 1870): HÄUBER 1991, pp. 16-17, with notes 54-56, pp. 20-21, with note 79; compare pp. 21-30 for my methods for determining the provenances of the new and of the old finds.

3. LA ROCCA 2015 (Laudatio on the occasion of the awarding of the Premio Daria Borghese literary prize to me): "Laudatio di Chrystina Häuber, 23 maggio 2015"; "Laudatio auf Chrystina Häuber, 23 May 2015" [Translation: C. Häuber]. Online at:

<https://FORTVNA-research.org/haeuber/Chrystina_Haeuber_Premio_Daria_Borghese_2015.html>.

For the `glove quote´ by Lucos Cozza, see: HÄUBER 2014, p. 1 with note 4. For the photos of these new finds from the Parker Collection, see: PARKER 1879; BRIZZI 1975; RAMIERI 1989; HÄUBER 1986, pp. 183-186, figs. 118-121; HÄUBER 1991, pp. 16-17, and pp. 42-79: "Parkerkat. 1-65"; HÄUBER 2015, pp. 40-41, 28th slide [a portrait of Parker]; CIMA, in: CIMA and TALAMO 2008, pp. 136-137, figs. 1; 2.

On the former kitchen garden of the Conservatori and the `giardino alla Romana´: HÄUBER 1991, pp. 80-81; HÄUBER 2005, p. 17, fig. 2, map of the Capitolium with the ground-plans of the Palazzo dei Conservatori and of the Palazzo Caffarelli, label: "GR" (`giardino alla Romana´); CIMA, in: CIMA and TALAMO 2008, pp. 138-139, figs. 3; 4, pp. 152-156, figs. 17-21: On the site of the former kitchen garden of the Conservatori/ the "Sala ottagona" (1876-1903)/ the `giardino alla Romana´, has now been erected the "Esedra di Marco Aurelio". For the "Sala ottagona": LANCIANI 1876; compare: HÄUBER 1991, p. 17 with note 59; HÄUBER 2021/2023, p. 164. On the newly [after 1870] discovered ancient statues exhibited in the "Sala ottagona": HÄUBER 1986, pp. 173-175, figs. 110-112; 114; HÄUBER 1991, pp. 19-21; pp. 80-191: catalogue "Sala ottagona 1-235"; CIMA, in: CIMA and TALAMO 2008, pp. 140-143, figs. 5-8.

4. HÄUBER 2013, pp. 150-152.

5. In the following I quote abbreviated passages from HÄUBER, Laokoon, with reference to the relevant Chapters.

6. Compare HÄUBER 2014, p. 140, Fig. 26. Compare Chapter I.1.; Appendix I, and Map 2, Lanciani's FUR, inter alia fols. 23; 30.

7. HÄUBER 2014, p. 11 with note 69. Lucos Cozza had asked me to study Lanciani's original excavation drawings in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana and then to reconstruct the course of the Servian city walls (see below, note 18). For these drawings and my first reconstruction of the Servian city walls in this area: HÄUBER 1990, passim and Karte 1. For my good friend Lucos Cozza (1921-2011), see: HÄUBER 2014, pp. XXI, 1-3; HÄUBER 2015; HÄUBER 2024.

8. Compare with Lanciani's excavation drawings [= here Fig. 1]: HÄUBER 1990, pp. 24-25 [Fig. 9: above Esq. b / Via Mecenate 35a; below: Esq. a], 30, 42; HÄUBER and SCHÜTZ 2004, pp. 84-93; p. 84, Fig. II.12 (= Esq. b / Via Mecenate 35a). For the reconstructions of the Servian city wall on the Mons Oppius by Lanciani [on the FUR], SÄFLUND [1932]: HÄUBER 2014, p. 11 with note 69, pp. 251-258, and Map 2 (= Lanciani's FUR, inter alia fols. 23; 30) [as well as Map 3 = here Fig. 2]; HÄUBER, Laokoon, Chapter III.3.1.; Chapter III.3.4.; Chapter III.5., note 146; Chapter III.6., note 147) .

9. DE ANGELIS BERTOLOTTI 1991, p. 115; HÄUBER 2014, p. 253 with note 19, HÄUBER, Laokoon, Chapter IV.2.6., at Punkt 4.).

10. HÄUBER, Laokoon, Chapter IV.2.8.

11. DE ANGELIS BERTOLOTTI 1991, pp. 116-118, Fig. 4.

12. HÄUBER and SCHÜTZ 2004, pp. 84-90, Fig. II.12-II.15.

13. HÄUBER and SCHÜTZ 2004, pp. 84-90, fig. II.12-II.15; HÄUBER 2014, p. 253 with notes 20-22.

14. SCHÜTZ 2014, p. 120, Fig. 9 [= here Fig. 3]. For the old state of the `city wall in the car repair shop´, see: HÄUBER and SCHÜTZ 2004, p. 86, Fig. II.14).

15. HÄUBER 2014, pp. 11, 69.

16. For my good friend Amanda Claridge (1 September 1949–5 May 2022), see HÄUBER 2024; HÄUBER 2021/2023, pp. 8, 785, and pp. 1246–1247 (Amanda's contribution to this volume).

17. see above, note 13.