In diesem Text werden die aktuellen Identifizierungs- und Lokalisierungsvorschläge für die Porta Triumphalis in Rom in der Kaiserzeit diskutiert:

- Kaiser Domitians Quadrifrons, der von Elefanten-Quadrigen bekrönt war (hier Figs. 19c; 19d), und der (irrtümlich) mit Domitians (angeblichem) Neubau der Porta Triumphalis identifiziert worden ist

Dieser Quadrifrons des Domitian ist (irrtümlich) im Heiligtum der Fortuna und der Mater Matuta lokalisiert worden, das in der heute noch zugänglichen Ausgrabung `Area sacra di S. Omobono´ (hier Figs. 58; 73; 74) zum Teil freigelegt wurde

Als Folge dieser irrtümlichen Hypothese haben dann einige Gelehrte (gleichfalls irrtümlich) vorgeschlagen, dass, in der Kaiserzeit, die Triumphzüge dieses Heiligtum (hier Figs. 58; 73; 74) von Westen nach Osten durchquert hätten

- die Porta Triumphalis auf dem `Beuterelief´ des Bogens des Divus Titus auf der Velia (hier Fig. 120) und auf einem Relief Marc Aurels (hier Fig. 19b); diese Porta Triumphalis ist leider nicht lokalisierbar

- der Arco di Portogallo (hier Figs. 3.5.1; 3.6; 64.1; 64.2), der früher die Via Flaminia / Via Lata / Via del Corso überbrückt hat, ist (irrtümlich) mit Domitians (angeblichem) Neubau der Porta Triumphalis identifiziert worden

Der folgende Text enthält Literaturangaben und viele Abbildungsnummern. Vergleiche FORTVNA PAPERS vol. III-1, S. 1097 ff. für die entsprechenden Bildunterschriften ("List of illustrations"), S. 1128, für die Abkürzungen ("Abbreviations") , und S. 1129 ff., für die Literatur ("Bibliography") .

Dieser Band ist open access auf unserem Webserver publiziert. Siehe: https://FORTVNA-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3.html

Addenda et Corrigenda zu FORTVNA PAPERS vol. III-1, pp. 649-650:

Chapter V.1.i.3.b); Section IV.). The Nollekens Relief, Domitian's sacrifice at his Porta Triumphalis, and the controversy concerning the location of this building

Tonio Hölscher, who wanted to know where in vol. 3-1, I have discussed Domitian's quadrifrons with quadrigas, drawn by elephants, was kind enough to answer me by E-mail on 26th November 2024 to my relevant response: that, as far as he knows, Domitian has not erected a new Porta Triumphalis, nor that Domitian's quadrifrons may be identified with the Porta Triumphalis (!).

Hölscher has alerted me to the facts that the Porta Triumphalis cannot possibly have been a quadrifrons, which, by definition, always bridged a crossroad, whereas the Porta Triumphalis could only have one passage, because it bridged the pomerium-line, the sacred boundary of the city of Rome (for the significance of the pomerium; cf. supra, in volume 3-1, p. 277 with n. 199).

Domitian's quadrifrons was, according to Martial, adorned by two golden statues of Domitian in chariots, drawn by elephants; cf. John Pollini (2017b, 125 with n. 123). This quadrifrons is known from Domitian's coins and from marble reliefs; cf. Pollini (2017b, 121, Fig. 19 [for one of Domitian's coins; here Fig. 19c], p. 122, Figs. 21; 22 [for two reliefs of Marcus Aurelius, representing Domitian's quadrifrons; here Fig. 19d]).

I had (as I see now, erroneously) written supra (in vol. 3-1, pp. 649-650), that Domitian had built a new Porta Triumphalis, adding to this that, in my opinion, Domitian's Porta Triumphalis cannot be located though. With my assumption of a new Porta Triumphalis, built by Domitian, I had, like many other scholars, followed Filippo Coarelli's relevant hypothesis (1968; 1988), who, in addition to this, has suggested, that Domitian's (alleged) Porta Triumphalis should be identified with Domitian's well-known quadrifrons, decorated with quadrigas, drawn by elephants (here Fig. 19c). For his relevant hypotheses; cf. also Filippo Coarelli ("Murus Servii Tullii"; Mura Repubblicane: Porta Triumphalis", in: LTUR III [1996] 333-334).

Coarelli (1996, 334) writes:

"Sulla base di questi dati, si è proposto (Coarelli [1968; 1988]) di identificare il duplice giano di età adrianea al centro dell'area sacra di S. Omobono, con una ricostruzione imperiale della p. T. [porta Triumphalis] (la cui prima redazione monumentale sarebbe da riconoscere negli archi di Stertinius, v.[edi; see below]). La presenza di un doppio arco in questa zona non può non essere collegata con il dexter ianus portae Carmentalis, ricordato in Liv. 2.49.8 e Ov., fast. 2.201-204 (v.[edi] porta Carmentalis). La stessa p. T. [porta Triumphalis] sarebbe da riconoscere nell'arcus Domitiani, ricordato da Marziale (8.65) in relazione con un tempio della Fortuna Redux (v.[edi]), da identificare con la Fortuna del Foro Boario: in quest'ultima, insieme a Mater Matuta, sarebbe da riconoscere le ``divinità tutelari della porta´´ ricordate da Flavius Iosephus [BJ VII.5.4; see below; my emphasis]".

Emilio Rodríguez Almeida ("Arcus Domitiani Fortuna Redux", in: LTUR I [1993] 92), quoted by John Pollini (2017b, 121, n. 108), wrote about Domitian's quadrifrons:

"Costruito da Domiziano nel 92 in previsione del ritorno dalla campagna marcomanno-sarmatica, viene descritto da Marziale (8.65-7.10) come un tetrapylon con quadrighe di elefanti. L'arco era solo una parte secondaria (altra dona) di un complesso progettato interamente da Domiziano, il cui fulcro fu il nuovo tempio di Fortuna Redux ... [my emphasis]".

See also Coarelli ("Fortuna Redux, Templum", in: LUR II [1995] 275-276, Figs. 104-107), where he quotes Martial (8.65) verbatim. For Martial's text, with an English translation; cf. also John Pollini (2017b, 125).

Reading again Martial's (8.65) text, I still find Coarelli's conclusions (1968; 1988; and 1996, 334) understandable, who believes that Martial alludes to the fact that Domitian erected his quadrifrons with elephants (here Fig. 19c) as a new Porta Triumphalis next to his Temple of Fortuna Redux.

Nevertheless, I follow now Hölscher's judgements (cf. supra) that Martial (8.65), who describes Domitian's quadrifrons with elephants, does not say, that this is the Porta Triumphalis (cf. infra, for my own translation of Martial's relevant passage), nor that we have any (other) proof for the assumption that Domitian actually erected a new Porta Triumphalis.

Filippo Coarelli (1995, 275-276) does not tell us, why Domitian had commissioned his (new) Temple of Fortuna Redux at all. Francesca Ghedini, like Emilio Rodríguez Almeida (1993, 92, quoted verbatim supra), mentions the achievement, Domitian intended to commemorate with the dedication of this temple: his victory in the Sarmatian War (AD 93). For this victory, the Senate had granted Domitian a triumph, but Domitian resigned this honour, accepted only in January of AD 93 an Ovatio de Sarmatis, and built `instead´ his Temple of Fortuna Redux. Domitian thus acted like Augustus in a similar situation in 19 BC, who, likewise instead of celebrating a triumph, had dedicated an Altar to Fortuna Redux.

To further illustrate this point, I, repeat in the following a passage, written for supra, vol. 3-1, pp. 289-290, n. 232, in Chapter I.2.:

``... F. GHEDINI 1986, 292, argues that Domitian's body language on Frieze A [of the Cancelleria Reliefs; here Figs. 1 and 2 drawing: Domitian is figure 6] can only be understood as hesitation, when the scene is interpreted as a profectio. In her opinion, Frieze A shows Domitian's adventus into Rome instead, after his victory in the Sarmatian War (93 AD). Since he resigned to celebrate the triumph, which he had been granted for this victory, Domitian's "gesto di modestia" (with n. 16), or his "pudore degli onori", is represented on Frieze A: Domitian is shown on his way to Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus to dedicate the "corona d'alloro" to him, as mentioned by Suetonius (Dom. 6). Cf. pp. 292-293: GHEDINI does not believe that Domitian's gesture with his right hand may be identified as "Machtgestus"... but suggests to read it as an "atto di omaggio" (towards Iuppiter obviously). Cf. p. 293 with n. 35: on Domitian's decision, instead of celebrating a triumph for his Sarmatian War, to build a Temple for Fortuna Redux, similarly as Augustus had done in 19 BC (cf. p. 292 with ns. 24, 25), who, instead of celebrating a triumph, had built an Altar for Fortuna Redux ....

For the triumphs, celebrated by Domitian; cf. D. KIENAST, W. ECK and M. HEIL 2017, 109 ...:

"Wichtige Einzeldaten ...

Herbst 83 Triumph über die Chatten; Siegername GERMANICUS ...

Jan.[uar] 93 Ovatio de Sarmatis [(vgl. [vergleiche] Martial 8, 8, 5)] [my emphasis] ...´´.

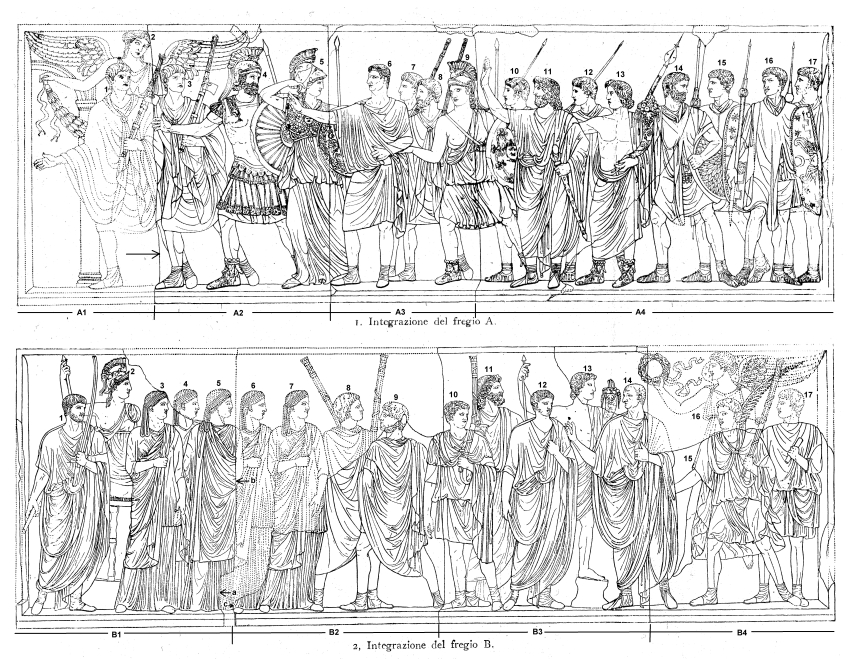

Cf. Figs. 1 and 2 drawing. F. Magis drawing of Frieze A and B of the Cancelleria Reliefs. From: F. Magi (1945, Tav. Agg. D 1 and 2). The slabs of both panels (A1-A4 and B1-B4) and the figures of both Friezes (1-17) are numbered, as in S. Langer and M. Pfanner (2018, 19, Abb. 2).

For ovatio; cf. Howard Hayes Scullard; Andrew William Lintott ("ovatio was a form of victory celebration less lavish and impressive than a triumph, probably of native Roman or Latin origin. It could be granted to a general who was unable to claim a full triumph ... He entered Rome on foot or horseback instead of in a chariot, dressed in a toga praetexta (not picta) and without a sceptre, wearing a wreath of myrtle instead of laurel, and the procession was much less spectacular ...", in: OCD3 [1996] 1084 [my emphasis]).

The above-quoted information proves the following: Domitian did not celebrate his victory in the Sarmatian War (AD 93) with a triumph, but accepted only in January of AD 93 an ovatio de Sarmatis, and built `instead´ his Temple of Fortuna Redux.

Nevertheless it seems at first glance, when reading Martial (8.65), who mentions Domitian's Temple of Fortuna Redux as already existing, as if the poet had himself seen Domitian in this very triumphal procession. This triumph, because Martial (8.65) mentions Domitian's Temple of Fortuna Redux, should (in theory) have been Domitian's triumph after his Sarmatian War - and that although Martial (8.8.5) knew perfectly well that Domitian had only celebrated an ovatio de Sarmatis (!).

I suggest this, because Filippo Coarelli (1995, 276) writes: "Anche se Marziale non indica esplicitamente il sito ove sorgeva l'edificio [i.e., Fortuna Redux, Templum], alcune indicazioni si desumono dal testo: il tempio era in una felix area, strettamente collegata al trionfo dell'imperatore (che presenta infatti la faccia dipinta di minio, purpurum iubar, ed è accolto dalla stessa Roma): siamo di conseguenza nel punto di accesso alla città, in corrispondenza della porta Triumphalis (v.[edi]), che è infatti ricordata subito dopo in modo esplicito (digna tuis ... porta triumphis non può significare altro, come pure l'indicazione che questo è l'aditus dell'urbe Martis) [my emphasis]".

When reading Martial's (8.65) text more carefully; cf. Pollini (2017b, 125, with an English translation and the author's comments), I realized that, although already mentioning in his text Domitian's Temple of Fortuna Redux, and reporting on one of Domitian's triumphs as an eye-wittness, Martial actually says the truth.

Addressing at the end of his epigram Domitian as "Germanice", thus citing the emperor's victory title `Germanicus´, which Domitian accepted after his victory over the Chatti in AD 83, and henceforth integrated into his titulature, Martial (8.65) obviously recalls Domitian's triumphal procession of AD 83 (!).

This is also, how John Pollini (2017b, 125, with ns. 122, 124) comments (in square brackets) the translation by S. Bailey (1993) of the following phrase in Martial (8.65):

"hic stetit Arctoi formosus pulvere belli

purpureum fundens Caesar ab ore iubar";

`Here stood Caesar [Domitian] beauteous, with the

dust of northern warfare [his victory over the Germans],

pouring a purplish radiance from his countenance´ [my emphasis]".

The Sarmatians, on the other hand, were not a `northern´ (i.e., a Germanic) tribe, but rather a large confederation of Iranian equestrian nomadic peoples; cf. supra, in volume 3-1, pp. 143, 289 with n. 232, p. 247 n. 82, p. 337, n. 304; and Max Cary and John Joseph Wilkes ("Sarmatae", in: OCD3 [1996] 1357).

Besides, Domitian was the first emperor to integrate his victory title `Germanicus´ into his official title; cf. supra, in vol. 3-1, pp. 134, 150.

In my opinion, Martial (8.65), by writing:

"haec est digna tuis, Germanice, porta triumphis",

intends to say:

`this porta [i.e., Domitians quadrifrons, adorned with quadrigas, drawn by elephants], Germanicus, [thus addressing Domitian by his victory title], is worthy your triumphs´; so also Pollini (2017b, 125).

Immediately after that, Martial's epigram (8.65) ends with the following line:

"hos aditus urbem Martis habere decet",

translated by S. Bailey; cf. Pollini (2017b, 125) as: "Mars' city deserves such an entrance".

Inter alia this final remark in Martial's epigram (8.65) has led Coarelli (1968; 1988; 1995; 1996), followed by Pollini (2017b, 125) and other scholars, to believe that Domitian's quadrifrons, decorated with two quadrigas, drawn by elephants (here Fig. 19c), was Domitian's (alleged) new Porta Triumphalis, by which henceforth the future triumphatores would enter Rome with their triumphal processions.

Let's now apply what we have just learned above to my (in part erroneous) formulations, supra, in vol. 3-1, at pp. 649-650 (at the beginning, I quote, what I wrote there):

``ChapterV.1.i.3.b); Section IV.).The Nollekens Relief, Domitian's sacrifice at his Porta Triumphalis, and the controversy concerning the location of this building

In my opinion, Pollini (2017b, 120 with n. 106) convincingly suggests that the Nollekens Relief (here Fig. 36) represents Domitian sacrificing in AD 89 immediately outside the Porta Triumphalis. Like Pollini (op.cit.), I assume that Domitian did that at the Porta Triumphalis, built anew by the emperor, and that Domitian would have started this triumph (which turned out to be his last) immediately after this ceremony ...

[Page 650] Filippo Coarelli's (wrong) location of Domitian's Porta Triumphalis at the "Area sacra di S. Omobono" was also followed by Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli and Mario Torelli (1976 ...

Within the `Area sacra di S. Omobono´ have been excavated two Republican Temples of Fortuna and of Mater Matuta. At the site in question, Domitian's quadrifrons (i.e., his Porta Triumphalis) was not found ...

Pollini (2017b, Figs. 21-23) follows also in this respect Coarelli (1988) by illustrating the same reliefs again, erroneously asserting that they all show Domitian's Porta Triumphalis ...

At the same time, Pollini follows Coarelli's likewise erroneous identification of the Temple of Fortuna at the Forum Boarium with that of Fortuna Redux, which, as we know, stood next to Domitian's Porta Triumphalis ...

Coarelli's relevant hypotheses have been refuted, apart from Neudecker (1990) also by myself; cf. Häuber (2005, 51-55, Section: " III.4. Die Porta Triumphalis" [with my reconstruction of the Republican Porta Triumphalis/ Porta Carmentalis], esp. p. 53 with ns. 385-390 [discussion of Coarelli's wrong location of Domitian's Porta Triumphalis ...

Personally I refrain from trying to suggest a location for Domitian's Porta Triumphalis ...

Paolo Liverani (2021, 88) ... does not mention in this context that in several of his earlier publications, he had suggested that Domitian's Porta Triumphalis should be identified with the former Arco del Portogallo [my emphasis]´´.

Correct would instead be the following formulations:

Cf. supra, in volume 3-1, p. 649:

ChapterV.1.i.3.b); Section IV.).The Nollekens Relief, Domitian's sacrifice at the Porta Triumphalis, and the controversy concerning the location of this building

In my opinion, Pollini (2017b, 120 with n. 106) convincingly suggests that the Nollekens Relief (here Fig. 36) represents Domitian sacrificing in AD 89 immediately outside the Porta Triumphalis. Like Pollini (op.cit.), I assume that Domitian would have started this triumph (which turned out to be his last) immediately after this ceremony [my emphasis] ...

Cf. supra, in volume 3-1, page 650:

Filippo Coarelli's assumption of Domitian's (alleged) Porta Triumphalis at the "Area sacra di S. Omobono" was also followed by Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli and Mario Torelli (1976 ...

Within the `Area sacra di S. Omobono´ have been excavated two Republican Temples of Fortuna and of Mater Matuta. At the site in question, Domitian's quadrifrons (i.e., his [alleged] Porta Triumphalis) was not found ...

Pollini (2017b, Figs. 21-23) follows also in this respect Coarelli (1988) by illustrating the same reliefs again, erroneously asserting that they all show Domitian's (alleged) Porta Triumphalis ...

At the same time, Pollini follows Coarelli's likewise erroneous identification of the Temple of Fortuna at the Forum Boarium with that of Fortuna Redux, which, as we know, stood next to Domitian's quadrifrons ...

Coarelli's relevant hypotheses have been refuted, apart from Neudecker (1990) also by myself; cf. Häuber (2005, 51-55, Section: " III.4. Die Porta Triumphalis" [with my reconstruction of the Republican Porta Triumphalis/ Porta Carmentalis], esp. p. 53 with ns. 385-390 [discussion of Coarelli's wrong location of Domitian's quadrifrons, Coarelli's (alleged) Porta Triumphalis ...

Personally I refrain from trying to suggest a location for Domitian's quadrifrons, his (alleged) Porta Triumphalis ...

Paolo Liverani (2021, 88) ... does not mention in this context that in several of his earlier publications, he had suggested that Domitian's (alleged) Porta Triumphalis should be identified with the former Arco del Portogallo [my emphasis]´´.

To this I should like to add now something else: I refrain likewise from trying to suggest a location for the Porta Triumphalis of the Imperial period (to this I will come back below).

My thanks are due to Franz Xaver Schütz, who, after this text had been published on our Webserver on 17th December 2024, has found the following article by Elena Köstner on the Internet, who has followed my reconstruction (2005) of the Porta Triumphalis of the Republican period; cf. Köstner ("``Triumphans Romam redit´´. Rom als Bühne für eine kommemorative Prozession", Hermes, 147, H. 1 (2019), pp. 21-41).

Let's now pursue the discussion of Filippo Coarelli's Porta Triumphalis of the Imperial period, (allegedly) built by Domitian :

Coarelli's (1968; 1988) above-mentioned hypotheses, concerning: Domitian's quadrifrons, his identification of Domitian's Temple of Fortuna Redux and of Domitian's (alleged) new Porta Triumphalis, were in toto followed by Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli and Mario Torelli (1976, "Arte Romana", schede 2 and 105), who followed Coarelli also in attributing the Cancelleria Reliefs (here Figs. 1 and 2 drawing) to Coarelli's (1968; 1988: alleged) "duplice giano" (`double quadrifrons´), which Bandinelli and Torelli, like Coarelli, attributed to Domitian.

See Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli and Mario Torelli (1976, "Arte Romana", scheda):

"2 ROMA AREA SACRA DI S. OMOBONO

Alla sbocco del vicus iugarius che congiungeva il Foro con il Portus Tiberinus, sul confine tra Foro Olitorio e Foro Boario, sorsero nel secondo quarto del VI secolo a. C., sul luogo occupato da capanne protostoriche, due templi (di cui uno solo è stato inividuato dai sondaggi archeologici) dedicati, secondo le fonti, a Fortuna e Mater Matuta ... [and about the two Republican temples of those goddesses, they wrote:] Davanti ai templi, che erano in stretto rapporto con il percorso del trionfo e con la Porta Triumphalis , L. Stertinius elevava nel 292 a. C. i primi due archi di trionfo coronati da statue dorate. Ultimo restauro in ordine di tempo, dopo quello seguito ad un incendio nel 213 a. C. è quello domizianeo, che ricostruisce i templi su di una platea di travertino, con un arco quadrifronte centrale in funzione di porta trionfale, come ci dimostrano monete e due rilievi aureliani nell'arco di Costantino (v.[edi scheda] n. 142 [ = here Figs. 19d, left; 19d, right]) [my emphasis]".

Cf. Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli and Mario Torelli (1976, "Arte Romana", scheda):

"105 ROMA, PALAZZO DELLA CANCELLERIA: RILIEVI DOMIZIANEI MUSEI VATICANI (EX LATERANESE) m 2,06 [i.e., The Cancelleria Reliefs; here Figs. 1 and 2 drawing]

... "Il monumento da cui provengono i rilievi ... è certo un arco trionfale, presumibilmente quadrifronte: si potrebbe pensare addiritura alla stessa porta triumphalis presso il tempio della Fortuna Redux (v.[edi] n. 2), ricostruito da Domiziano in occasione del trionfo sui Chatti dell'83 d.C. [my emphasis]".

As we have seen above, Domitian had, contrary to the just-quoted assumption of Bianchi Bandinelli and Torelli (1976, "Arte Romana", scheda 105), only after his victory in the Sarmatian War (AD 93) rebuilt the pre-existing Temple of Fortuna Redux.

Domitian's (alleged) Porta Triumphalis:

his quadrifrons (here Fig. 19c), adorned with two quadrigas drawn by elephants,

and the real Porta Triumphalis of the Imperial period (here Figs. 19b;120)

As mentioned supra (in vol. 3-1, p. 650), I have refuted that part of Coarelli's hypotheses, which concerns his identification of his (alleged) "duplice giano" in the `Area sacra di S. Omobono´ with Domitian's (alleged) Porta Triumphalis.

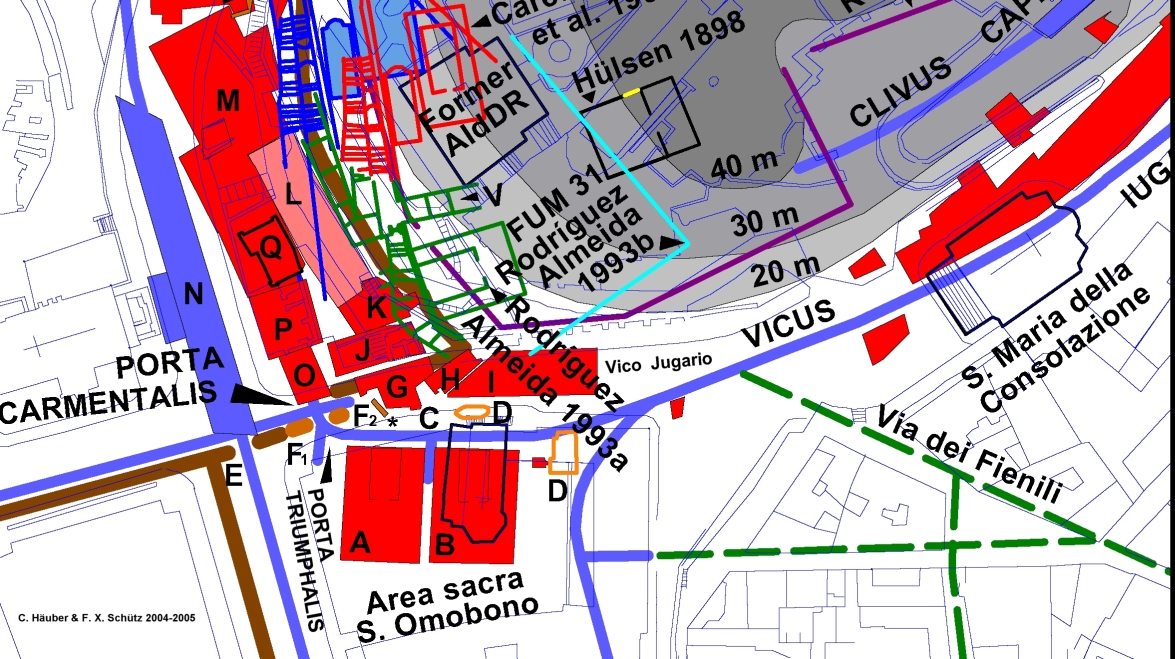

Cf. Häuber (2005, 53):

"Coarellis [with n. 385] Identifizierung seines hadrianischen doppelten Janus der `Area sacra di S. Omobono´ mit der kaiserzeitlichen Porta Triumphalis folge ich nicht, 1.) weil dieser Vorschlag auf seiner [with n. 386] von Wiseman (1990) [with n. 387] widerlegten Identifizierung der im Tempel der `Area sacra di S. Omobono´ verehrten Fortuna mit der Fortuna Redux basiert, 2.) weil es sich bei dieser Architktur gar nicht um einen doppelten Janus, sondern um eine Via Tecta handelt, 3.) weil er [with n. 388] irrtümlich behauptet, daß kaiserzeitliche Münzen und Reliefs, auf denen verschiedene Bogenmonumente erscheinen, seinen ``doppio giano´´ zeigen, und 4.), weil er irrtümlich behauptet, daß diese Darstellungen auch die Porta Fenestella [with n. 389] wiedergeben, die er mit dem N-Eingang zur `Area sacra di S. Omobono´ am Vicus Iugarius identifiziert (vgl. [vergleiche] hier Abb. 2, "C") [= here Fig. 74; my emphasis]".

In my notes 385-389, I provide references and further discussion.

For our maps Abb. 1-5 (in high resolution), published in Häuber (2005); cf. <https://fortvna-research.org/texte/HAEUBER_2005.html>.

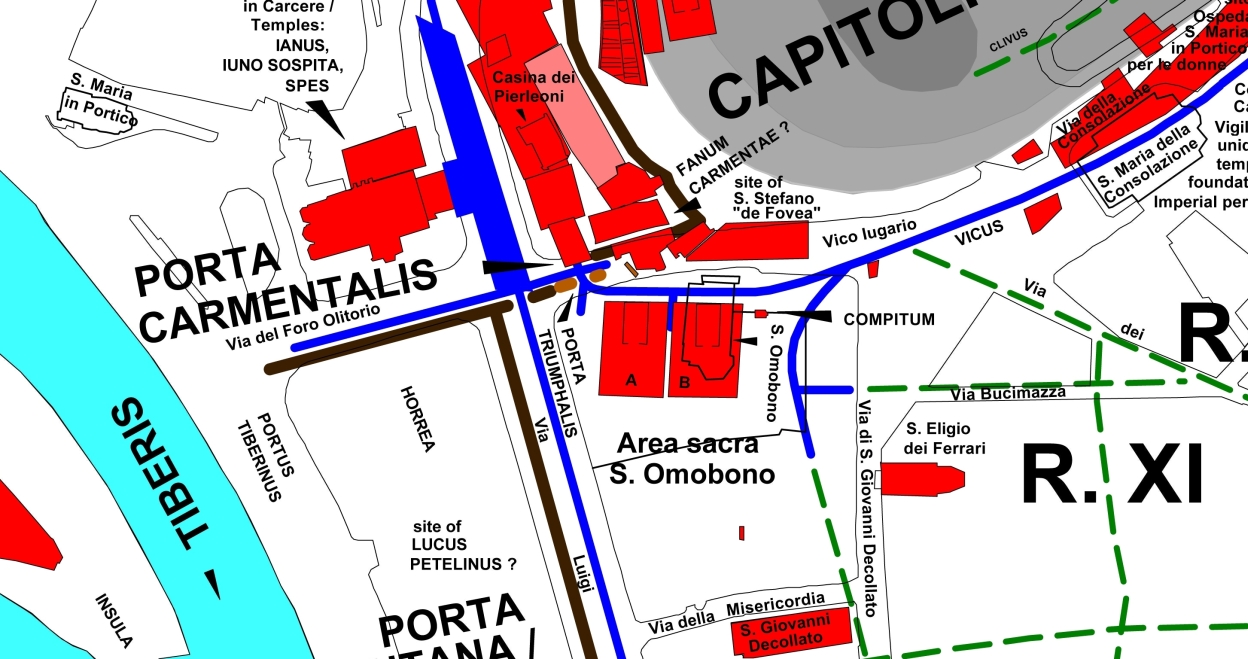

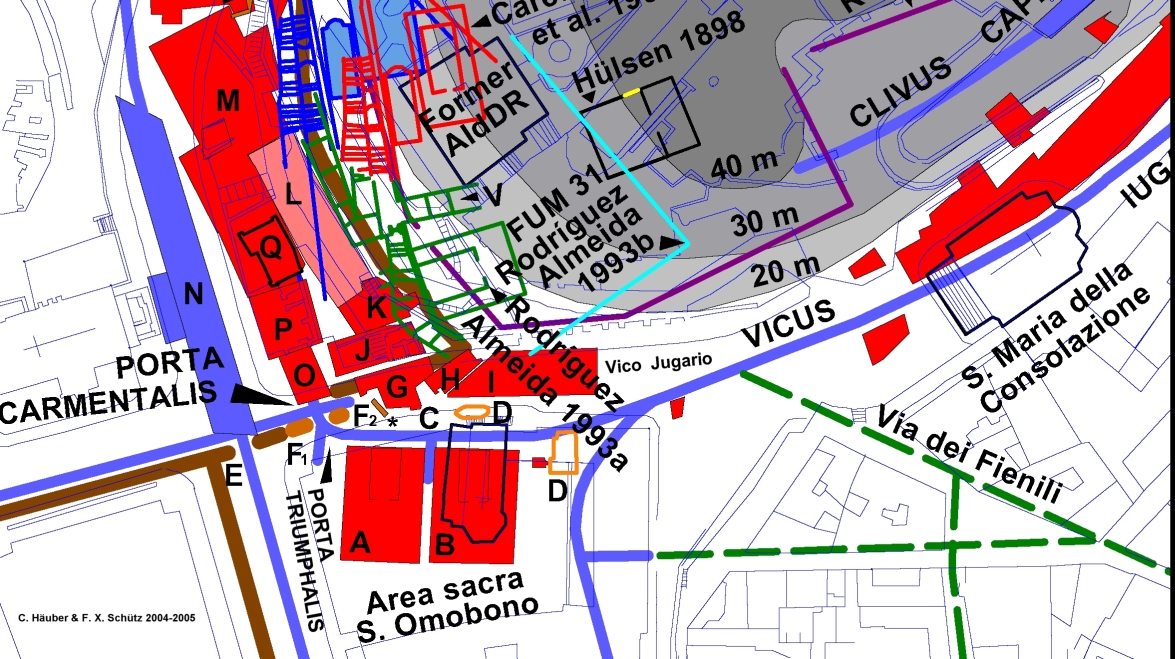

Fig. 74. Map of the Capitol, detail. C. Häuber & F.X. Schütz, "AIS ROMA". From: Häuber (2005, 17, Abb. 2).

For an update of this map; cf. <https://fortvna-research.org/maps/HAEUBER_2014_Map5_Kapitol_Palatin_Rom.html>.

Fig. 73. Rome map, showing the area between the Capitoline Hill and the Caelian, detail. C. Häuber and F.X. Schütz, "AIS ROMA", reconstruction. From: C. Häuber 2014a, Map 5 (enlarged and updated in 2023). For an explanation of the cartographic details; cf. Häuber (2014a, 874-875); and infra, at Appendix V.

For another recent map of this area, cf. Fig. 58 (2022, update of a map, first published in Häuber 2017) cf. <https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/HAEUBER_2022_Visualization_results_book_Domitian_maps.html> :

See, in addition to this, Häuber (2005, 55):

"Da ich Coarellis Identifizierung seines ``doppio giano´´ der `Area sacra di S. Omobono´ als kaiserzeitliche Porta Triumphalis ablehne, folge ich ebensowenig seinem Vorschlag [with n. 412], daß es sich bei der von ihm postulierten Straße, die unter diesem ``doppio giano´´ in W-O Richtung verlaufen sei, um jene nur bei Triumpzügen begangenen Straße gehandelt habe [my emphasis]".

In my note 412, I write: "s.[iehe] F. COARELLI 1968, 89, vgl. [vergleiche] S. 62, Abb. a; ders. 1988, 367, Abb. 82".

In the following, I repeat again some more observations concerning the excavations at the `Area sacra di S. Omobono´, published supra, in vol. 3-1, p. 650:

``At the site in question, Domitian's quadrifrons (i.e., his [alleged] Porta Triumphalis) was not found, as asserted by Coarelli [1968; 1988], but instead six pillars of a via tecta; cf. Richard Neudecker (1990, 176 with ns. 13, 14). Neudecker has also pointed out that the reliefs, illustrated by Coarelli in this context (1988), do not show exclusively the imperial Porta Triumphalis, as asserted by Coarelli, but in reality different arches. Pollini (2017b, Figs. 21-23) follows also in this respect Coarelli (1988) by illustrating the same reliefs again, erroneously asserting that they all show Domitian's Porta Triumphalis [my emphasis]´´.

Only Pollini's third relief (2017b, 122-123 with ns. 110, 111, Fig. 23 [= here Fig. 19b]) actually represents the Porta Triumphalis of the Imperial period, which has only one single passage. Because this is, therefore, not Domitian's quadrifrons, the temple to the left of this Porta Triumphalis is, of course, not Domitian's Temple of Fortuna Redux, as nevertheless believed by Coarelli (1968; 1988), Bianchi Bandinelli and Torelli (1976, "Arte Romana", scheda 142 ), and by Pollini (op.cit.).

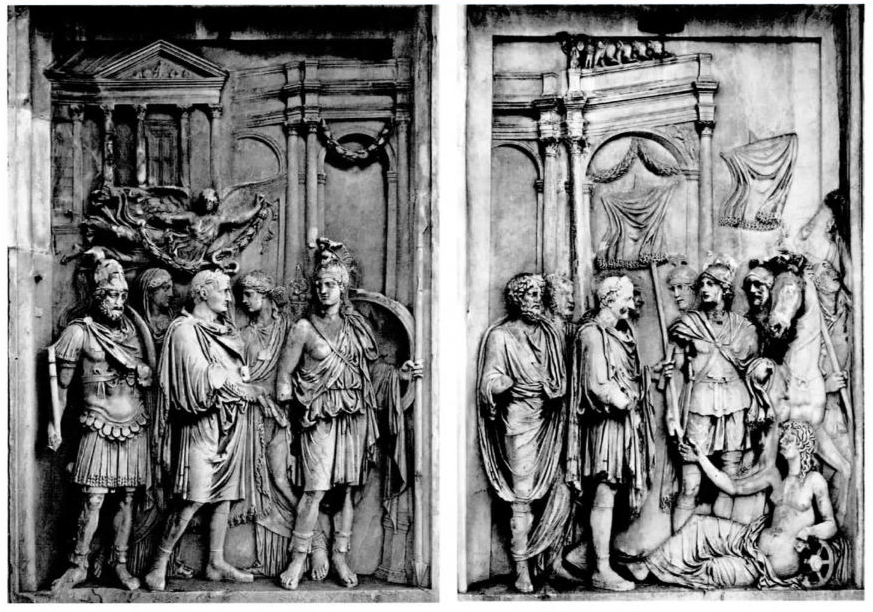

Fig. 19b. "Triumph of Marcus Aurelius, Palazzo dei Conservatori, Musei Capitolini (Ryberg 1967, 15-20, pl. IX, fig. 9a)". From J. Pollini (2017b, 123, Fig. 23).

In my opinion, Pollini's two reliefs (2017b, 122, Figs. 21; 22 = here Fig. 19d) show Domitian's quadrifrons (here Fig. 19c), but, as Tonio Hölscher has explained to me (cf. supra): because this structure is a quadrifrons, it cannot possibly be identified with a Porta Triumphalis. Nevertheless, Coarelli (1968; 1988), Bianchi Bandinelli and Torelli (1976, "Arte Romana", scheda 142) and Pollini (2017b, 121, Fig, 19) have (erroneously) identified Domitian's quadrifrons with Domitian's (alleged) Porta Triumphalis.

Fig. 19d, left: "Relief representing the adventus of Marcus Aurelius, from the Arch of Constantine (Ryberg 1967, pl. XXIII, fig. 19)"; right: "Relief representing the profectio of Marcus Aurelius, from the Arch of Constantine (Ryberg 1967, pl. XXII, fig. 18)". From J. Pollini (2017b, 122, Figs. 21; 22).

Cf. Inez Scott Ryberg, Panel reliefs of Marcus Aurelius (New York, Archaeological Institute of America, 1967).

For the two reliefs of Marcus Aurelius (here Fig. 19d, left and 19d, right); cf. also Diana E.E. Kleiner (1992, 291, Fig. 258 and p. 289, Fig. 256). Kleiner (1992, 291) wrote about the adventus-relief (her Fig. 258 = here Fig. 19d, left): "The emperor returned to Rome in 176 after the successful completion of his northern campaign ... The adventus scene (see fig. 258) represents Marcus' arrival in Rome ...".

Luckily we still have altogether 11 (!) reliefs that originally belonged to the same Arch of Marcus Aurelius - all illustrated by Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli and Mario Torelli (1976, "Arte Romana", scheda 142). And because to this series belongs also the relief Fig. 19b, `the triumph of Marcus Aurelius AD 176´, a comparison of both reliefs (Fig. 19d, left with Fig. 19b) clearly shows that the relief Fig. 19d, left does not represent the Porta Triumphalis as well.

Besides, the relief, illustrated on Fig. 19d, left, shows Marcus Aurelius in an adventus-ceremony in AD 176, when he had just returned to Rome after this victorious military campaign. At this very moment it would have been impossible for Marcus to enter the City of Rome through the Porta Triumphalis.

The reason being that after a military victory, a Roman general or emperor would transgress the sacred boundary of Rome (the pomerium) through the Porta Triumphalis only once - at his triumph.

The problems involved for a Roman magistrate cum imperio or for a Roman emperor, who had conducted victorious military campaigns, and wished to be granted a triumph for it, were complex.

First of all the problem, not to transgress the pomerium before the triumph. Second, in order to be granted by the Senate a triumph, they had to negotiate with the Senate; all this has been discussed in detail supra, in vol. 3-1, p. 277 with ns. 198, 199, p. 397 with ns. 456, 457, p. 398 with n. 458, pp. 569-585.

I, therefore, repeat two passages, written for supra, vol. 3-1, pp. 569, 570 (they refer to the representation of Vespasian on Frieze B of the Cancelleria Reliefs, here Figs. 1 and 2 drawing: Vespasian is figure 14):

``Vespasian on Frieze B is thus deliberately shown as still standing outside the City of Rome, that is to say, within the area militiae. Vespasian's imperium (exactly as that of any magistrate cum imperio) that he had received in AD 67 from Nero with the command to conduct this war [i.e., the Great Jewish Revolt or War, AD 66-73], would have ended precisely at the sacred boundary of Rome (cf. supra, at n. 456, in Chapter III.)´´. Cf. p. 570: ``But like a magistrate cum imperio, who was coming back from a victorious military campaign, Vespasian (in theory ! - see below) had to stay outside the pomerium (cf. supra, n. 199, in Chapter I.1.1.) until the Senate would grant such a victorious general a triumph, as it also did in the case of Vespasian for his victories in the Great Jewish Revolt (cf. supra, n. 198, in Chapter I.1.1., and at n. 458, in Chapter III.). The reason being, that, when a magistrate cum imperio transgressed the pomerium, he automatically lost his imperium, that is to say, his command over his troops. - And without his imperium, he could, of course, not lead his troops in the triumphal procession he desired [my emphasis]´´.

Or in other words: because of the inherent legal prescriptions, Marcus Aurelius in AD 176 could only have `entered the City of Rome through the Porta Triumphalis, together with his victorious soldiers and together with the entire triumphal procession´, after the Senate would have granted him a triumph for this victorious military campaign - de Germanis et de Sarmatis, as it was called in this case (see below). This actually happened in due course, as the marble relief (here Fig. 19b) proves.

The marble relief (here Fig. 19b) shows the Emperor Marcus Aurelius in his triumph of AD 176 (which he celebrated together with his son Commodus), as he is about to drive his triumphal chariot through the Porta Triumphalis.

Kienast, Eck an Heil (2017, 132), who provide the precise data concerning this triumph of Marcus Aurelius, seem to doubt that Commodus had participated in this triumph:

"Marc Aurel (7. März 161 - 17. März 180) ...

23. Dez.[ember] 176 Triumph de Germanis et de Sarmatis (HA v. Comm. 12, 5), gemeinsam mit Commodus ? ...".

Scholars, who know the relief (here Fig. 19b), which had belonged to the above-discussed Honorary Arch for Marcus Aurelius and Commodus, know that this assumption is proven by two of its 11 reliefs:

Originally, Commodus had likewise been represented on Fig. 19b as riding together with Marcus Aurelius in this chariot in their joint triumph in AD 176, but after Commodus' assassination and damnatio memoriae, Commodus' portrait has been erased from this relief; cf. Bianchi Bandinelli and Torelli (1976, "Arte Romana", scheda 142). So also Diana E. E. Kleiner (1992, 292-294, with Fig. 261); as well as Hans-Ulrich Cain (2019, 508-510; quoted verbatim supra). Cain (2019, 509) adds to this that also the "Liberalitas-Relief am Konstantinsbogen" had originally comprised a representation of Commodus.

The `spoils scene´ of the Arch of Divus Titus on the Velia (here Fig. 120; cf. supra, in vol. 3-1, p. 297), and this relief of Marcus Aurelius (here Fig. 19b) contain the only representations of the Porta Triumphalis of the Imperial period discussed in this Study.

But, as already said above, I have no idea, where this Porta Triumphalis was located .

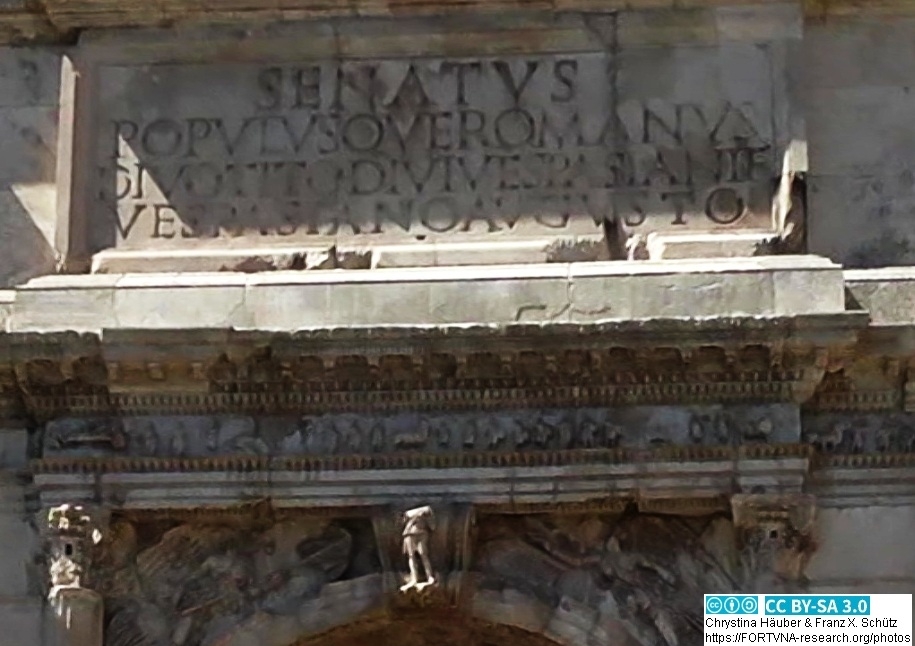

Fig. 120. The Arch of Divus Titus on the Velia in Rome. Cf. Paolo Liverani (2021, 83-84): "We can exemplify what is at stake by examining the decoration on the Arch of Titus ... a monument whose construction was planned by the Roman Senate shortly before the premature death of Titus, but which had to be built and finished under his brother and successor, Domitian". Cf. Diana E.E. Kleiner (1992, 183): "The inscription on the attic of the Arch of Titus indicates that the monument was erected by the senate and people of Rome in honour of the divine Titus, son of the divine Vespasian".

The bay of the Arch of Divus Titus on the Velia is decorated with two famous relief panels, the "spoils scene" and the "triumph relief", and at the apex of the vault of this arch there is a relief representing "the apotheosis of Titus"; cf. Diana E.E. Kleiner (1992, 187, Fig. 155, p. 188, Fig. 156, p. 189, Fig. 157). On the `spoils scene´ stands at the far right an arch (i.e., the Porta Triumphalis), through which the triumphal procession is marching, This arch is crowned by what seems to be statue groups. The centre of those statues is occupied by Domitian on horseback, accompanied to his left by his walking personal patron goddess Minerva, both are flanked on either side by the triumphal quadrigas of Vespasian and Titus, each of which pulled by four horses; cf. Diana E.E. Kleiner (1992, 185, Fig. 155). Photos: Courtesy Franz Xaver Schütz (4-IX-2019).

But the Porta Triumphalis, represented on the `spoils scene´ of the Arch of Divus Titus (here Fig. 120) differs in one important respect from the Porta Triumphalis, visible on the relief of Marcus Aurelius (here Fig. 19b). To illustrate this point, I repeat in the following a passage from supra, vol. 3-1, p. 675:

``As Diana E.E. Kleiner [with n. 477] has realized, on the `triumph relief´ of this Arch of Divus Titus [here Fig. 120] which shows the triumph of AD 71, only Titus is shown in a triumphal quadriga, whereas Vespasian and Domitian are missing. And that, although in reality all three of them had celebrated this triumph together (cf. supra, in vol. 3-1, at Chapter V.1.i.3.)), both Vespasian and Titus riding in their own triumphal quadrigas, accompanied by Domitian on horseback. Elsewhere, on the `spoils relief´, the other horizontal panel in the bay of this Arch of Divus Titus, this has actually been represented. The attic of the arch (i.e., the Porta Triumphalis), that stands at the far right of this relief, and through which the triumphal procession is marching, is crowned by what seem to be statue groups (cf. here Fig. 120) - as has been noted by many scholars: in reality, a triumphal arch, carrying the statues of the three triumphatores Vespasian, Titus and Domitian, could, of course, only have been erected after the triumphal procession had taken place [my emphasis]´´.

See for this `addition´ of the statues of the three triumpatores Vespasian, Titus and Domitian to the Porta Triumphalis, also supra , in vol. 3-1, p. 300 with n. 244 . To this I will come back below.

Also the former Arco di Portogallo was not Domitian's (alleged) Porta Triumphalis

The following passage is likewise a quote from supra vol. 3-1, p. 650 (there I have summarized my research concerning the Porta Triumphalis of the Imperial period in Häuber (FORTVNA PAPERS vol. II, 2017); cf. https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP2.html:

``See also Häuber (2017, 111-112 n. 56, pp. 168, 178-202, esp. p. 200 [with a summary of the most recent discussion concerning the various locations of the Porta Triumphalis and concerning the suggestion that the Arco di Portogallo could be identified as a pomerium-gate and/ or as Domitian's Porta Triumphalis; a hypothesis which I myself do not follow], Section: "The pomerium of Claudius and some routes possibly taken by Vespasian, Titus and Domitian on the morning of their triumph in June of AD 71", discussing inter alia G. FILIPPI's and P. LIVERANI's 2014-2015 relevant findings) ...

Paolo Liverani (2021, 88) ... does not mention in this context that in several of his earlier publications, he had suggested that Domitian's [alleged] Porta Triumphalis should be identified with the former Arco del Portogallo. This fact he has mentioned earlier in this essay; cf. Liverani (2021, 84, with ns. 10-12). For a discussion of Liverani's relevant hypothesis; cf. Häuber (2017, summarized above). See now Liverani (2023, 116-117 with ns. 11-13; i.e., the Italian version of his essay of 2021) [my emphasis]´´.

To those statements, I should like to add now the reason, why I do not follow Paolo Liverani's hypothesis, according to which Domitian's (alleged) Porta Triumphalis should be identified with the former Arco di Portogallo.

Cf. Häuber (2017, 111, n. 56): "... Friedrich Rakob 1987, 704 n. 39 wrote: ``Dass der wahrscheinlich als Pomerium‐Bogen errichtete Arco di Portogallo das neue, hadrianische erhöhte Strassenniveau voraussetzt, hat bereits Lugli a.O. [1961] 222 betont, auch wenn Rodríguez [Almeida 1978‐80] 203 Anm. 23 den Bogen nach seiner Bautechnik eher flavisch‐trajanisch datieren wollte. Vgl. auch MORETTI [1948] 116; CA [Carta Archeologica] Roma 2, 160 Nr. 64 (Niveau: 13.00 m ü. M.)´´ (my emphasis)".

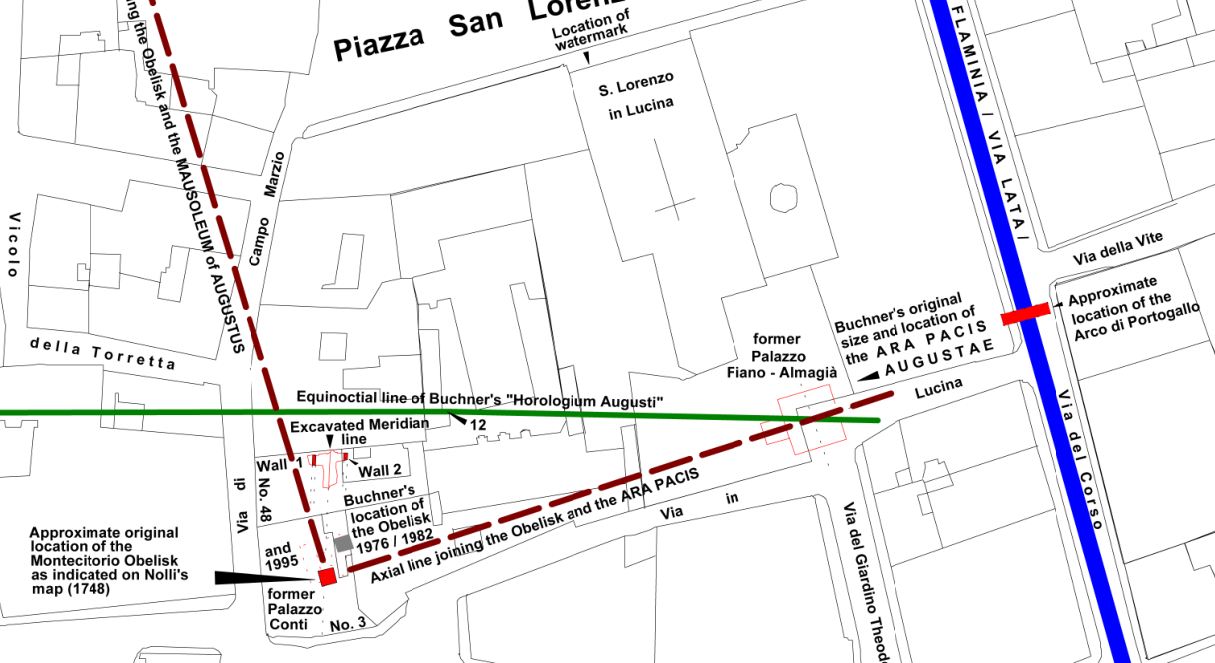

That Hadrian actually raised the level of the Campus Martius by

several meters is well known. See Rakob (1987, 689-712), providing

reconstruction drawings of the levels of the area, which were based

on corings made for this purpose. These reconstruction drawings show

the Augustan, Flavian, Hadrianic and Severan periods, and comprise

the (alleged) Horologium Augusti (in reality a Meridian

instrument; cf. C. HÄUBER 2017, 17-18, 582-597, and passim),

the Ara Pacis Augustae, and the Via Flaminia/ Via

Lata/ Via del Corso; cf. pp. 707-712, his Section: "Rom -

Nördliches Marsfeld Synoptische Tabelle der Bodenniveaus (Abb. 7

["Höhendiagramme für Horologium Augusti, Ara Pacis, Via

Flaminia (1.-20. Jh.])". Rakob described in detail and

demonstrated with those reconstruction drawings, what we also learn

from Mario Torelli (1992; 1999) about the original location of the

Ara Pacis Augustae, to which we will now turn.

I quote in the following the observations, made by

Mario Torelli (1992; 1999) concerning the

Ara

Pacis Augustae,

because that building stood originally very close to the former Arco

di Portogallo (see our

map

Fig. 3.6,

published in Häuber 2017, which is illustrated below). See Häuber

(2017, 357, n. 155):

"cf. M. Torelli 1992, 108 with n. 13, Fig. 1; id. 1999, passim; p. 74: ʺNelle epoche successive e forse fino al IV sec. d.C., anche se non abbiamo altri ricordi letterari, epigrafici o numismatici dellʹaltare, lʹa. P. A. [i.e., l' ara Pacis Augustae] ha certamente continuato a svolgere un ruolo importante nella propaganda imperiale; e infatti, nel II sec. d.C., per impedire che il continuo, forte innalzamento del livello del suolo circostante obliterasse il monumento, si è provveduto a garantirne lʹaccessibilità, racchiudendo lo spazio attorno al recinto entro un muro in laterizio ... dalla sommità del quale, posta al livello dei fregi figurati, era possibile ammirare ancora il recinto con la straordinaria sua decorazioneʺ; cf. LTUR V (1999) 285‐286 (with additional bibliography)".

Cf. Mario Torelli, 1992, ʺTopografia e iconologia. Arco di Portogallo, Ara Pacis, Ara Providentiae, Templum Solisʺ, Ostraka 1, 105‐131; Mario Torelli 1999, ʺPax, Augusta, Araʺ, in: LTUR IV (1999) 70‐74, Figs. 17‐22.

See for the former Arco di Portogallo still in situ the map by Antonio Tempesta (1593):

Fig. 64.1. Detail of Antonio Tempesta's bird's-eye-view map of Rome (1593) with his representation of the Arco di Portogallo, which at this time still bridged the Via Flaminia/ Via Lata/ Via del Corso. In the following, I repeat a text passage from above, in vol. 3-1, p. 122, in Chapter Introductory remarks and acknowledgements: `And when we were discussing the location of the former Arco di Portogallo on the Via Flaminia/ Via Lata/ Via del Corso, which was destroyed in 1622, Franz Xaver Schütz has made a relevant research and found a hitherto not recognized representation of the former Arco di Portogallo on Tempesta's bird's-eye-view map of Rome (1593; cf. here Fig. 64.1)´. Antonio Tempesta has even labelled this Arch: "arcus por / tugalli". See the inserted box on here Fig. 64.1, with the enlarged detail of Tempesta's map with the labelled Arco di Portogallo, which we have turned around, so that the inscription is legible.

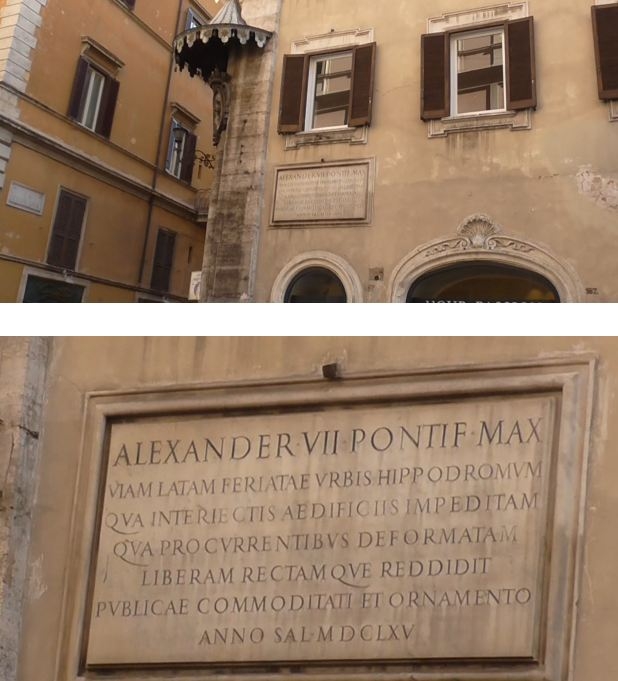

The following photo is published in Häuber (2017, 64-65):

Fig. 3.5.1. Inscription which is inserted into the façade of the Palazzo on the east side of the Via del Corso, at approximately the site where the Arco di Portogallo once stood. ʺThis arch was removed in 1662 by [Pope] Alexander VII in order that the Corso might be widenedʺ; cf. Samuel Ball Platner and Thomas Ashby (1929, 33, s.v. Arco di Portogallo). This Palazzo stands between the junctions of Via del Corso and Via della Vite and Via del Corso and Via in Lucina, and close to the original location of the Ara Pacis Augustae. Cf. Fig. 3.6, labels: Via del Corso; Approximate location of the Arco di Portogallo; Via della Vite; Via in Lucina; Buchnerʹs original size and location of the ARA PACIS AUGUSTAE. Some scholars regard the former Arco di Portogallo as a gate in the sacred boundary of Rome, the pomerium. Cf. M. Torelli (1992, 105 with n. 1). See here ns. 56, 136, 306; chapter VIII. EPILOGUE; and the Contribution by Filippo Coarelli in this volume, at pp. 667-670 (photo: F. X. Schütz 1‐X‐2016).

The following map is published in Häuber (2017, 67, as Fig. 3.6). In this map the former location of the Arco di Portogallo is marked; cf. Häuber (2017, 66):

Fig.

3.6. Detail of the map shown on Fig. 3.5 [=

here Fig.

59].

Map of the Campus

Martius

showing the area, where the Montecitorio Obelisk and the Ara

Pacis

were found with integration of Edmund Buchnerʹs reconstruction of

the Ara

Pacis.

The

map is oriented so that North is in the middle of the top border, or

in other words, it is oriented according to `grid north´. The grid

is based on the following coordinate system: Roma 1940 Gauss Boaga

Est with a transverse Mercator projection. This map shows the output

displayed by the ʺAIS ROMAʺ without cartographic revision ...

This

map is based on the official photogrammetric data of Roma Capitale

which appear in the background. They were generously provided by the

Sovraintendente ai Beni Culturali of Roma Capitale. C. Häuber,

reconstruction. This map was made with the ʺAIS ROMAʺ (C. Häuber

and F.X. Schütz 2017).

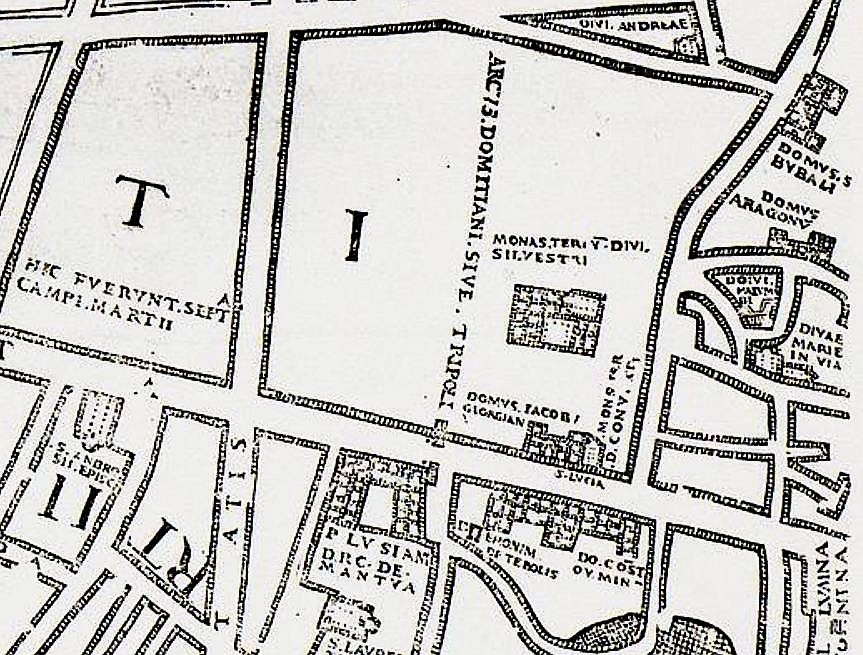

Franz Xaver Schütz alerts me to the fact that, already on the Rome map of Leonardo Bufalini (1551; here Fig. 64.2), the site of the Arco di Portogallo on the Via Flaminia / Via Lata / Via del Corso is marked by a labelling, which expresses the opinion that this arch was built by Domitian (!): ARCVS. DOMITIANI. SIVE. TRIPOLI.

For the Rome map by Leonardo Bufalini (1551); cf. Häuber and Schütz (2004, 118-119, the caption of Abb. II.24): "Die Romkarte von Leonardo Bufalini (1551); Detail. Es handelt sich um die erste exakt vermessene Romkarte der Neuzeit ... Norden befindet sich auf dieser Karte in der Mitte des linken Kartenrandes und die Beschriftungen sind so unterschiedlich angebracht, dass, ganz gleich wie die Karte gedreht wird, immer ein paar auf dem Kopf stehen ...".

Fig. 64.2. Rome map by Leonardo Bufalini (1551), detail: the area of the Via Flaminia / Via Lata / Via del Corso. Note that

Bufalini's map is not oriented North, as our Rome maps today. Therefore, on the detail of the map, illustrated here, the Via Flaminia /

Via Lata, does not run from North-West to South-East, but instead from LEFT to RIGHT. Bufalini called this road VIA LATA:

see the remaining two letters of its name [L A] T A on the far left of this road.

To the right of the lettering: ARCVS. DOMITIANI. SIVE. TRIPOLI, of which Bufalini drew its two piers, standing in reality on the West-side

and on the East-side of the Via Flaminia / Via Lata, he has marked: MONASTERIV[m]. DIVI. SILVESTRI. The location of `S. Silvestro´ shows that Bufalini

with this `Arch of Domitian´ referred to the former Arco di Portogallo.

Francesco Ehrle (1911, 33) wrote about the toponyms, marked by Bufalini on his map (1551), which referred to the former Arco di Portogallo:

"Le indicazioni inscritte sulla pianta; Foglio G:

Arcvs Domitiani sive Tripoli. [With n. 9; my emphasis]".

Ehrle (1911, 33, n. 9) wrote: "L’arco di Portogallo. L’Anonimo Magliabecchiano lo chiama arcus trophali, v.[edi] Jordan-Huelsen, III, 465. MARLIANUS, p. 97: Vocatur autem nunc arcus Tripoli [my emphasis]".

See also Ehrle's discussion (1911, 33) of the lettering on Bufalini's map (1551, Foglio G), which referred to the palazzo, which stood immediately adjacent to the Western pier of the Arco di Portogallo on the Via Flaminia / Via Lata:

"P[alatium] Lusi[t]ani. [With n. 14; my emphasis]".

Ehrle (1911, 33-34, note 14) wrote:

"Sulla storia di questo Palazzo Ottoboni-Teano, v.[edi] F. Albertini, De mirabilibus novae urbis Romae ed. A. Schmarsow, [page 34] p. 24, nota 3. Comunemente si dice che, essendo stato questo palazzo, contiguo all'arco di Domiziano, per parecchio tempo abitato dall’ambasciatore Portoghese, l’arco quindi sia stato chiamato l’arco di Portogallo. Però nel 1551 il suddetto ambasciatore aveva un’altra abitazione (v.[edi] qui sotto p. 34). Inoltre nel Censo di Roma del 1526-27 lo troviamo nel palazzo Savelli-Orsini nel Theatrum Marcelli, v.[edi] Archivio della Soc. Rom., XVII (1894), 507. Quindi potrebbe sembrare più probabile l’opinione che deriva il nome moderno dell’ arco e per conseguenza 1’ epiteto « Lusitanum » dato al palazzo, dalla dimora che ivi fece il cardinale Giorgio Costa, arcivescovo di Lisbona, dal c.[irca] 1476 al 1508; v. l. c. Però l’Albertini, il quale scrisse il suo opuscolo fra il 1506 ed il 1509, non sembra conoscere queste denominazioni. Quella dell’arco di Portogallo si trova nel Giettito di via Lata del 1538, pubblicato dal chiar. Commendatore Lanciani nel Bull. Comun. [i.e., BullCom] XXX (1902), 235; cf. Lanciani, Storia degli scavi, III [1908], 73 (1565), 174, 221, 237 [my emphasis]".

Cf. Francesco Ehrle S.I., Roma al tempo di Giulio III La pianta di Roma di Leonardo Bufalini del 1551 riprodotta dall'esemplare esistente nella Biblioteca Vaticana a cura della Biblioteca medesima con introduzione di Francesco Ehrle S. I. (Roma: Danesi Editore 1911).

Francesco Ehrle (1911) did not add a bibliography to his book. As we have seen above, Ehrle (1911, 33 n. 9) mentioned for the Arco di Portogallo "Jordan-Huelsen, III" and "Marlianus".

From what Ehrle (1911, 28) wrote, we learn that he referred to: Heinrich Jordan and Christian Hülsen, Topographie der Stadt Rom im Altertum I.3 (Berlin et al.: Weidmann 1907). See Ehrle (1911, 25, n. 6) on the second edition of the book by Bartolomeo Marliani (1488-1566: Vrbis Romae Topographia, 1548), which he had consulted.

Ehrle (1911, 33-34) does not explain, why the former Arco di Portogallo has been called `Arcus Domitiani´ by Bufalini. For lack of time, I have decided not to begin an in-depth study on this subject in his context, which is why unfortunately also I myself cannot provide so far an answer to this question.

Could the triumphatores (of the Imperial period) choose their own Porta Triumphalis ?

This is by no means a new idea, as I only found out, when writing this text; cf. Samual Ball Platner and Thomas Ashby (1929, 418, s. v. Porta Triumphalis):

"a gate through which a Roman general, who was celebrating a triumph, passed at the beginning of his march. It is mentioned in five passages (Cic. in Pis. 55; Tac. Ann. i. 8; Cass. Dio lvi. 42; Suet. Aug. 100; Joseph. Bell. Iud. vii. 5. 4), but only the last contains any topographical indications ... Four views have been held as to the character of this gate and its site ... (3) that it was merely a name given to any gate through which a victorious general entered the city, or to a temporary arch erected at any point along the line of march ([Lucia] Morpurgo, BC [i.e., BullCom] 1908, 107-150) ... [my emphasis]".

Cf. Lucia Morpurgo, "La porta trionfale e la via dei Trionfi"; BullCom 36 (1908) 109-150.

In Häuber (2017), I have discussed similar observations

concerning the Porta Triumphalis in the Imperial period,

published by Mary Beard (2007) and T.P. Wiseman (2007; 2008b)

Cf. Häuber (2017, 180):

"I thus follow T.P. Wisemanʹs assumption that ``different triumphatores might use different routes´´ (cf. id. 2007, 448 with n. 27, with a discussion of this controversy [my emphasis]). See also T.P. Wiseman (2008b, 390‐391), where he discusses this idea in more detail, coming on p. 391 to the following conclusion: ``It is quite possible (to borrow for a moment the authorʹs [i.e., Mary Beardʹs 2007] habit of scepticism towards received ideas) that the whole notion of a single Porta Triumphalis is a chimaera [my emphasis]´´. T.P. Wiseman (2008b, 391) adds also another thought to this subject, that we should consider. He suggests that the individual `Porta Triumphalis´, by which, in the imperial period, a victorious commander intended to enter the city of Rome together with his triumphal procession, was not necessarily chosen, because it stood on the line of the contemporary pomerium [my emphasis]".

Cf. Häuber (2017, 184):

"M. Beard (2007, 96) assumes with good reasons the `Porta Triumphalis´, which Vespasian, Titus (and Domitian) had chosen for their triumphal procession, somewhere to the north of the Theatres of Pompey, Balbus and Marcellus ‐ and in the vicinity of the Iseum Campense, we might add, since it was there, where Vespasian and Titus had stayed the night before. T.P. Wiseman (2008b, 390‐391), who follows Beardʹs suggestion, identifies this specific `Via [corr.: Porta] Triumphalis´ with the triumphal Arch of Claudius, which was incorporated into the arches of the Aqua Virgo ... [my emphasis].

Cf. Figs. 3.5; 3.7 [= here Figs. 58; 59], labels: PORTA FLAMINIA/ PORTA DEL POPOLO; VIA FLAMINIA/ VIA LATA; AQUA VIRGO; Arch of CLAUDIUS; ISEUM [CAMPENSE]; Via del Plebiscito; Structure C: so‐called ARA MARTIS; VILLA PUBLICA?/ DOMUS?; Piazza Venezia; Via Cesare Battisti; THEATRUM POMPEI; THEATRUM BALBI; THEATRUM MARCELLI".

For

our maps Figs.

3.5; 3.7,

published in Häuber (2017), now updated and called Figs.

58; 59;

cf.

https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/HAEUBER_2022_Visualization_results_book_Domitian_maps.html

cf.

Häuber (2017, 198):

"I also thank T.P. Wiseman for ... discussing also this latter point with me, who alerts me to the precise meaning of Josephusʹ (BJ VII.4.130) relevant expression; a fact which I had previously overlooked, (erroneously) assuming that Vespasian, Titus (and Domitian) had gone to the Porta Triumphalis of Republican date at the foot of the Capitoline (i.e., to the Porta Carmentalis). He wrote me by email on 25th June 2017: ``Vespasian and Titus go back from the Porticus Octaviae to the triumphal gate. Thatʹs absolutely clear in the Greek; itʹs the only thing the verb anachorein can mean´´ (my emphasis)".

Cf. Mary Beard, The Roman Triumph (The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA 2007); T.P. Wiseman 2007, ʺThree notes on the triumphal routeʺ, in: A. Leone, D. Palombi and S. Walker (eds.), Res bene gestae. Ricerche di storia urbana su Roma antica in onore di Eva Margareta Steinby, LTUR Suppl. IV, Roma 2007, pp. 445-449; T.P. Wiseman 2008b, ʺRethinking the Triumph: Mary Beard, The Roman Triumph (The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA 2007)ʺ, JRA 21, 389-391.

As I have only realized now, John Pollini (2017b, 123 with n. 114) has translated Flavius Josephus' (which he quotes: BJ 7.130) verb "anachorein" differently, by writing: "Thereupon, Vespasian and Titus ``withdrew to the Porta Triumphalis [with n. 114; my emphasis]´´".

In his note 114, Pollini writes: "Beard (2007, 99 with n. 58) who translates `to go back´. As she argues this would have been in the opposite direction from where Coarelli [1968; 1988] locates the Porta Triumphalis. The verb can also mean `to withraw´or `retire´ from something". To this I will come back below.

Compare for this subject also Tonio Hölscher ("Die Stadt Rom als triumphaler Raum und ideologischer Rahmen in der Kaiserzeit", in: Fabian Goldbeck and Johannes Wienand (eds.), Der Römische Triumph in Prinzipat und Spätantike (Berlin; Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 2016), pp. 283-315).

My thanks are due to Franz Xaver Schütz for providing me with this publication.

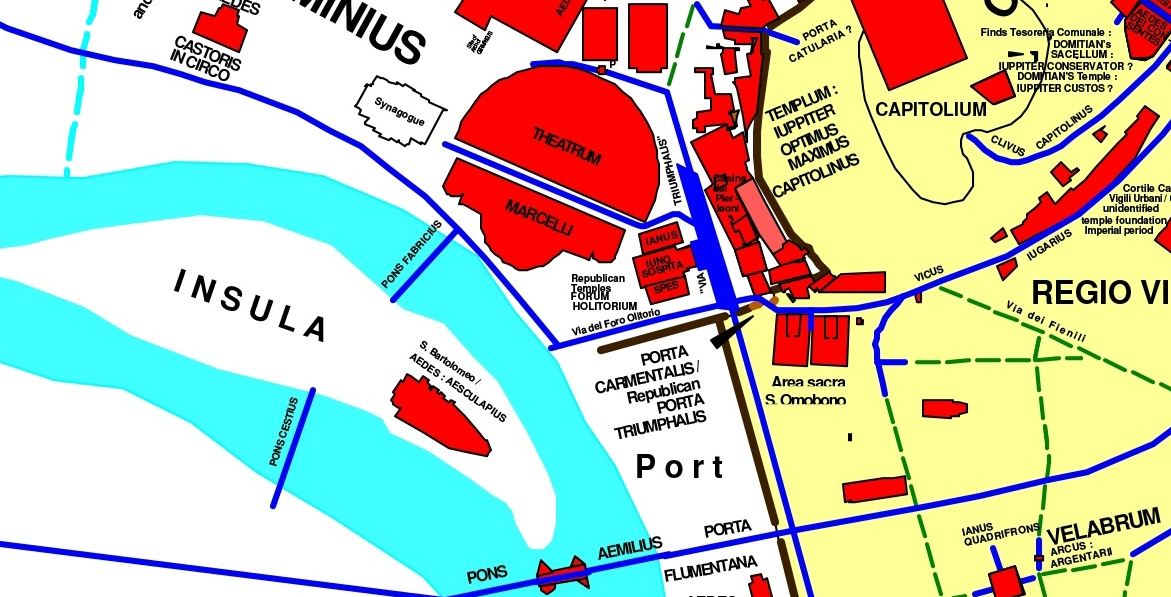

Hölscher (2016, 291, Abb. 9.2) illustrates a reconstruction of the `route of the triumphal procession´ (in the Imperial period): "Abb. 9.2: Rom, Stadtzentrum: Route des Triumphweges (Hubert Vögele, Heidelberg)". This drawing is based on the Rome map by Francesco Scagnetti and Giuseppe Grande (1979), a fact, which is not mentioned in the caption of this illustration.

By choosing this "Route des Triumphweges", Hölscher (2016, 291, Abb. 9.2) shows that he too (like myself 2005, 53, 55, quoted verbatim supra) does not follow Coarelli's (1968; 1988) suggestions, according to which the triumphal processions of the Imperial period marched -

(see for the following Coarelli's plan [1988, 454, Fig. 112] of the sanctuary of Fortuna and Mater Matuta; cf. J. Pollini 2017b, 121, Fig. 20; LTUR II [1995] Fig. 112):

a) along a (non existing) road, oriented from West to East, that, according to Coarelli, (allegedly) passed through the sanctuary of Fortuna and Mater Matuta at the `Area sacra di S. Omobono´ (i.e., the relatively small excavated area of this former sanctuary), and, likewise from West to East, -

b) under Coarelli's (alleged) "duplice giano" (`double quadrifrons´) of the Hadrianic period, that stood, according to Coarelli, between the two Republican temples of those two goddesses.

In this "Route des Triumphweges"; cf. Hölscher (2016, 291, Abb. 9.2), it is rather assumed that those triumphal processions of the Imperial period followed a road, running some distance to the south and parallel to Coarelli's (alleged) road, and likewise oriented from West to East.

And immediately after having passed those two Republican temples, it is assumed in this "Route des Triumphweges", that the triumphal processions turned in a right angle left, following a road, oriented from South to North, that led to the Vicus Iugarius. The latter detail of this "Route des Triumphweges" follows a road, marked on Scagnetti and Grande's map (1979), but note that on this map this road is marked at the wrong location (cf. infra).

Hölscher (2016) does not mention in his text, where he locates the Porta Triumphalis of the Imperial period, nor shows Vögele's drawing of their "Route des Triumphweges"; cf. Hölscher (2016, 291, Abb. 9.2), where they assume this Porta Triumphalis (!).

Another surprise consists in the fact that their "Route des Triumphweges"; cf. Hölscher (2016, 291, Abb. 9.2) only begins at the Circus Flaminius, although we learn from Josephus (cf. M. Beard 2007, 96, who quotes: "BJ 7.123-131"; cf. Häuber 2017, 198) that the triumphal procession of Vespasian, Titus and Domitian in June of AD 71 had led through "the theatres", as Josephus writes: according to Mary Beard those of Pompey, Balbus and Marcellus, not only the theatre of Marcellus, as drawn on this route; cf. Hölscher (2016, 291, Abb. 9.2).

Besides, also their section of the "Route des Triumphweges" of the Imperial period, which leads through the sanctuary of Fortuna and Mater Matuta; cf. Hölscher (2016, 291, Abb. 9.2), is exactly like the one, suggested by Coarelli (1968; 1988, 454, Fig. 112), impossible, and that for the following reasons.

Because for its first part through the sanctuary of Fortuna and Mater Matuta, the "Route des Triumphweges" of the Imperial period; cf. Hölscher (2016, 291, Abb. 9.2), which is oriented from West to East, there is no ancient road, which the triumphal processions could have marched along.

This part of Vögele's/ Hölscher's "Route des Triumphweges" rather follows approximately the northern boundary of the next modern city block to the south. Also for the second part of this route, which is oriented from South to North and leads to the Vicus Iugarius, there is no ancient road, which the processions could have followed. There actually was an ancient road in this area, but that ran parallel to the east of the road, drawn on Scagnetti and Grande's map (1979); unfortunately we do not know neither the name, or the date of this ancient road.

See our map of the area, Häuber (2014, Map 5 = here Fig. 73);

cf. <https://fortvna-research.org/maps/HAEUBER_2014_Map5_Kapitol_Palatin_Rom.html>,

- where I have marked the precise area of the excavated part of this sanctuary, labelled: "Area sacra S. Omobono", and the precise location of the ancient road to the East of the two Republican temples, in part located within the excavated area, which was oriented from South to North and led to the Vicus Iugarius.

"Hubert Vögele, Heidelberg", who drew this "Route des Triumphweges; cf. Hölscher (2016, 291, caption of Abb. 9.2), and Hölscher himself, either by drawing this part of their route of the triumphal processions of the Imperial period, or by publishing it, did not consider the fact that the excavated `Area sacra di S. Omobono´ of this sanctuary, which I have marked on our Map 5, does by no means comprise the entire former sanctuary, which certainly extended further to the south and further to the east.

See for those facts again the plan, published by Filippo Coarelli (Foro Boario 1988, 454, Fig. 112 [= LTUR II [1995] "Fig. 112. Fortuna et Mater Matuta, aedes. Area sacra di s. Omobono e pendici meridionali del Campidoglio"]).

See also Häuber (2013, 160, for the excavation of the sanctuary of Fortuna and Mater Matuta):

"Die Ausgrabung ist heute noch zugänglich und wird als `Area sacra di S. Omobono` bezeichnet. Der Besucher sollte sich jedoch vergegenwärtigen, dass das archaische Heiligtum wesentlich größer als die sichtbare Ausgrabungsfläche gewesen sein muß";

cf. < https://fortvna-research.org/texte/Archaeologische_Stadtforschung_Rom.html >, quoting:

Giuseppina Pisani Sartorio ("Fortuna et Mater Matuta, Aedes", in: LTUR II [1995] 284):

"Lo scavo e quindi lo studio dell'area sono ancora sostanzialmente incompleti; le indagini finora eseguite, a partire della scoperta avvenuta nel 1937-38, hanno saggiato solo una minima parte dell'intero santuario arcaico, mentre meglio note sono le fasi repubblicane e imperiali [my emphasis]".

It is, therefore, in my opinion, completely out of the question that in the Imperial period the triumphal processions could have marched through this sanctuary of Fortuna and Mater Matuta, as assumed by Filippo Coarelli (1968; 1988) and by Hubert Vögele and Tonio Hölscher in this "Route des Triumphweges"; cf. Hölscher (2016, 291, Abb. 9.2).

POST SCRIPTUM

Only after I had finished writing this text, Franz Xaver Schütz found on 13th December 2024 the article about the Porta Triumphalis by Michael Pfanner (1980), in which the author has already come to (almost) the same conclusions concerning Domitian's quadrifrons as I myself 44 years later, and presented above in this text (!). In the following, I will, therefore, quote the relevant passage from Pfanner's (1980) article.

Cf. Michael Pfanner, "Codex Coburgensis Nr. 88: die Entdeckung der Porta Triumphalis (Taf.114)", RM 87 (1980) 327-334.

Michael Pfanner (1980, 327-328) writes:

"Über die porta triumphalis wissen wir wenig. Das einzig Sichere ist, daß durch sie das Heer beim Triumph in Rom einzog [with n. 1]. Genaue Lage, Aussehen und Bedeutung sind unbekannt. Die zahlreichen Thesen bleiben hypothetisch [with n. 2] ...

Für das Aussehen der porta triumphalis haben wir nur einen Anhaltspunkt, und das ist die Bezeichnung als porta. Demnach handelt es sich um ein Stadttor. Zwar kommt [page 328] bei einigen Triumph- [with n. 4] und Adventusszenen [with n. 5] ein eintoriger Bogen vor, den man gewöhnlich für die porta triumphalis hält, da jedoch immer die Angabe der Stadtmauer fehlt, könnte auch ein anderer Bogen gemeint sein [with n. 6]. Ein öfters abgebildeter Quadrifrons, der aufgrund verschiedener Kombinationen als ein domitianischer Neubau der porta triumphalis angesehen wird, und an den man weitreichende Schlußfolgerungen knüpfte, bleibt besser aus der Diskussion [with n. 7]. Er ist nämlich nie im Kontext eines Triumphes nachgewiesen. Das entscheidende Argument scheint mir zu sein, daß der Quadrifrons in der gleichen aurelischen Reliefserie nur bei Adventus und Profectio erscheint, während der Triumphzug durch einen eintorigen Bogen führt [with n. 8; my emphasis]".

In his notes 1-6, Pfanner provides references and further discussion.

In his note 7, he writes: "Mart. 8, 65 beschreibt eine "porta triumphis digna", die man mit

der porta triumphalis und Darstellungen eines Quadrifrons (domitianische und aurelische Münzen, aurelische Reliefs am

Konstantinsbogen, historischer Fries des Konstantinsbogens) zu identifizieren versucht, s. RE VII A 1, 374 f. (Kähler) und

Coarelli a.O. [i.e., here F. Coarelli 1968] 68. 71 f. Abb. 1. 2. 5. 6. Es ist aber nicht bewiesen, daß Martial mit diesem

poetischen Ausdruck die porta triumphalis meint, noch, daß der Quadrifrons damit zusammenhängt, noch, daß es sich

immer um den gleichen Quadrifrons handelt [my emphasis]".

In his note 8, he writes: "Richtig Scott Ryberg a.O. [i.e., here I. Scott Ryberg 1967] 32 f. Abb. 9 a. 18. 19 [= here Fig. 19b; Fig. 19d, right; Fig. 19d, left] .

- Auch die Tempel im Hintergrund sind verschieden [my emphasis]".

Note that also Pfanner (1980, 333 with n. 49) discusses the arch, which is represented on the far right of the "Beuterelief" (the `spoils relief´) of the Arch of Divus Titus on the Velia (here Fig. 120).

But before summarizing Pfanner's (1980) relevant observations, let me alert you to Eric M. Moormann's (2023) article, who has not only studied the `spoils relief´ (here Fig. 120), but also in great detail the represented spoils and their history and meaning over time.

Cf. Eric M. Moormann, "Chapter 13 Judaea at the Tiber: Sacred Objects from Judaea and Their New Function in Imperial Rome", in: Reading Greek and Hellenistic Roman Spolia. Objects, Appropriation and Cultural Change (Euhormos: Greco-Roman Studies in Anchoring Innovation, 3), Leiden: Brill 2023, pp. 238-262. My thanks are due to Eric Moormann for sending me this article.

Eric M. Moormann (2023, 250 (writes):

"In the southern relief [of the Arch of Divus Titus on the Velia; here Fig. 120], aptly called ‘Beuterelief’, [with n. 60] troops carry the spoils on two biers or fercula towards an arch, seen as the temporary triumphal arch or porta triumphalis. On its outer side are a Victoria (as on the outer side of the arch itself) and dates of a date palm, symbol of Judaea. On top are, on the right, the four horses of a quadriga in a frontal position next to four more horses, clearly representing the chariots of Titus and Vespasian, accompanied by Domitian on horseback and a female deity, perhaps Minerva. [with n. 61; my emphasis]".

In his note 60, Moormann writes: "Thus, Pfanner 1983: 50; Eberhardt 2005: 264. See Pfanner 1983: 50-55, pls. 54-67; Yarden 1991; Eberhardt 2005: 264–267; Millar 2005; Östenberg 2009".

In his note 61, he writes: "Pfanner 1983: 72. The ‘identity’ of the Arch remains unclear (Pfanner 1983: 71–72; Eberhardt 2005: 267). Katarzyna Balbuza (in Goldbeck and Wienand 2017 [corr.: 2016]: 270–271, fig. 8.6) suggests that the triumphators are represented on top of the Arch through which the triumphal procession enters the city on the southern relief of the Arch of Titus (fig. 13.1 [= here Fig. 120]) [my emphasis]".

Cf. Eberhardt, B., ‘Wer dient wem? Die Darstellung des Flavischen Triumphzuges auf dem Titusbogen und bei Josephus (B.J. 7.123–162)’, in J. Sievers, G. Lembi (eds.), Josephus and Jewish History in Flavian Rome and Beyond (Leiden 2005) 257–277;

Goldbeck, F., Wienand, J. (eds.), Der römische Triumph in Prinzipat und Spätantike (Berlin-Boston 2017 [corr.: 2016]);

Millar, F., ‘Last Year in Jerusalem. Monuments of the Jewish War in Rome’, in J. Edmondson, S. Mason, J. Rives (eds.), Flavius Josephus and Flavian Rome (Oxford 2005) 101–128;

Östenberg, I., Staging the World. Spolia, Captives, and Representations in the Roman Triumphant [corr: Triumphal] Procession (Oxford 2009);

Yarden, L., The Spoils of Jerusalem on the Arch of Titus. A Re-Investigation (Stockholm 1991).

As we have just learned, Eric M. Moormann (2023, 250), after his survey of the subject, comes, concerning the arch that is represented on the far right of the `spoils relief´ (here Fig. 120), to the following conclusions:

this arch is "seen as the temporary triumphal arch or porta triumphalis [my emphasis]". And in his note 61, Moormann writes: "The ‘identity’ of the Arch remains unclear (Pfanner 1983: 71–72 ... [my emphasis]".

In my opinion, this arch may be identified with the Porta Triumphalis, through which `the triumphal procession of Vespasian, Titus and Domitian of June AD 71 is marching´. The above-mentioned statues of the triumphatores Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian (with his patron-goddess Minerva), appearing on top of this arch (here Fig. 120), have, in my opinion, been added by Domitian's artists to their representation of the already existing Porta Triumphalis. To this I will come back below.

Let's now turn to Michael Pfanner's (1980) opinion concerning this arch, which is visible on the `spoils relief´ (here Fig. 120); an article, which Eric M. Moormann (2023) has not discussed.

Because of those statues of Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian (here Fig. 120), Pfanner (1980, 333 with n. 49) believes that this arch cannot possibly be a representation of the Porta Triumphalis, but that it should instead be identified as an "Ehrenbogen" (`honorary arch´). Pfanner argues as follows:

"Der Bogen kann aber zum Zeitpunkt des Triumphes noch gar nicht gestanden haben: Die Verbindungen sind gedanklicher Art, die Gegenstände allerdings bleiben in sich real. Unrealistisch in diesem Sinn wäre es gewesen, die porta triumphalis mit Figuren zu bekrönen [my emphasis]".

If Pfanner is right, the problem remains that on this `spoils relief´ (here Fig. 120) the triumphal procession of Vespasian, Titus and Domitian is marching through this arch, and that this historical event is, of course, `documented´ in this relief `in retrospect´. We should also consider the following fact: even provided, the arch on this relief (here Fig. 120) was not the Porta Triumphalis, but instead an "Ehrenbogen´, as Pfanner (1980) suggests, also that honorary arch - decorated with these statues of the triumphatores Vespasian, Titus and Domitian - could only have been erected after this triumphal procession had actually entered the City of Rome through the Porta Triumphalis (!).

I am mentioning this fact here, because Flavius Josephus (BJ VII.5.4) states explicitly, that the triumphal procession of Vespasian, Titus and Domitian in June of AD 71 had marched through the Porta Triumphalis (thus transgressing the pomerium, the sacred boundary of the City of Rome). This proves, by the way, that at the time a gate called `Porta Triumphalis´ existed.

To further illustrate this point, I quote in the following in more detail a passage from FORTVNA PAPERS vol. II, that has already been quoted above.

Cf. Häuber (2017, 198):

"In the case of Vespasian, Josephus is more explicit: after pronouncing this invitation to the soldiers to have breakfast, Vespasian himself ``withdrew to the gate [i.e., the Porta Triumphalis´]´´, as H.St.J. Thackeray (1928) translates. From what follows is clear that Vespasian goes there together with Titus (and Domitian). Because, once at the Porta Triumphalis: ``Here the princes [i.e., Vespasian, Titus (and Domitian)] first partook of refreshment, and then, having donned their triumphal robes and sacrificed to the gods whose statues stood beside the gate, they sent the pageant [i.e., the triumphal procession] on its way, driving off through the theatres, in order to give the crowds an easier view´´ (Josephus, BJ VII.5.4; translation: H.St.J. Thackeray (1928)).

.... I also thank T.P. Wiseman ... for discussing also this latter point with me, who alerts me to the precise meaning of Josephusʹ (BJ VII.4.130) relevant expression; a fact which I had previously overlooked, (erroneously) assuming that Vespasian, Titus (and Domitian) had gone to the Porta Triumphalis of Republican date at the foot of the Capitoline (i.e., to the Porta Carmentalis). He wrote me by email on 25th June 2017: ``Vespasian and Titus go back from the Porticus Octaviae to the triumphal gate. Thatʹs absolutely clear in the Greek; itʹs the only thing the verb anachorein can mean´´ (my emphasis)".

Also Eric M. Moormann (2023, 244) comes to the conclusion that the triumphal procession of Vespasian, Titus and Domitian in June of AD 71 had started in the Campus Martius: "The triumph began in the Campus Martius where the two honorands [i.e., Vespasian and Titus] had slept in or near the Iseum Campense. [With n. 27, providing references and further discussion]".

CONCLUSIONS

I, therefore, maintain my above-made suggestion that the arch appearing on the `spoils relief´ (here Fig. 120) may, with confidence, be identified with the Porta Triumphalis. The reason being that we witness on this relief, how the triumphal procession of Vespasian, Titus and Domitian in June of AD 71 is marching through that arch, which Flavius Josephus (BJ VII.5.4), who described also this very detail of the triumphal procession, explicitly called the `Porta Triumphalis´.

And because it seems logical to assume that real statues of the three triumphatores Vespasian, Titus and Domitian, could not possibly have been added to the Porta Triumphalis at all, let alone before this event, I maintain likewise my further suggestion: that the representations of those statues (here Fig. 120) were only `added´ afterwards to this arch. And, as I now also suggest, presumably not in reality, but only by the artists, who designed this `spoils relief´ for the Arch of Divus Titus.

Addendum of 6th January 2025:

The Republican porticus (here Fig. 102.6), located at the foot of the Capitolium, between the Forum Holitorium and the Vicus Iugarius, which is oriented from North-West to South-East and leads towards the Porta Triumphalis/ Porta Carmentalis within the Servian city Wall, has been identified by Filippo Coarelli as `Porticus Triumphi´. On our map Abb. 2 (2005 = here Fig. 74), the ground-plan of this porticus is marked with the letters "O"; P".

Cf. Coarelli ("Porticus Triumphi", in: LTUR IV [1999] 151, Figs. 55-56); Coarelli ("Forum Holitorium", in: LTUR II [1995] 299, Figs. 123, 126-126a; 127-128); Häuber (2005, 17, Abb. 2, labels: "O"; "P", p. 43, n. 290, p. 46, ns. 316, 319, pp. 51-52, n. 368).

For our maps Abb. 1-5 (in high resolution), published in Häuber (2005); cf. <https://fortvna-research.org/texte/HAEUBER_2005.html>.

Fig. 74. Map of the Capitol. C. Häuber & F.X. Schütz, "AIS ROMA". From: Häuber (2005, 17, Abb. 2).

Datenschutzerklärung | Impressum