Preview FORTVNA PAPERS 3, Domitian, Palatine, Nollekens Relief

V.1.i.3.b) J. Pollini's

discussion (2017b) of the allegedly `lost´ Nollekens Relief (cf. here Fig. 36),

which he compares with the Cancelleria Reliefs (cf. here Figs. 1; 2; Figs. 1

and 2 drawing) and Domitian's `Domus Flavia´/ Domus

Augustana. With The Contribution by

Amanda Claridge

ChapterV.1.i.3.b); Section I.

Introduction

"The presence of the goddess Roma in Martial's adventus scene is mirrored in the Nollekens Relief.

A sacrifice related to a triumph would have been an appropriate subject to decorate

a stately space in Domitian's Domus Flavia. Military victories leading to

triumphs were a basis for deification after death, as in the case of Domitian's

father and brother, even if for Domitian the outcome turned out to be different".

John Pollini (2017b, 126).

With "Martial's adventus scene", Pollini (2017b,

126) refers to Martial's epigram (8, 65), which he discusses on p. 125.

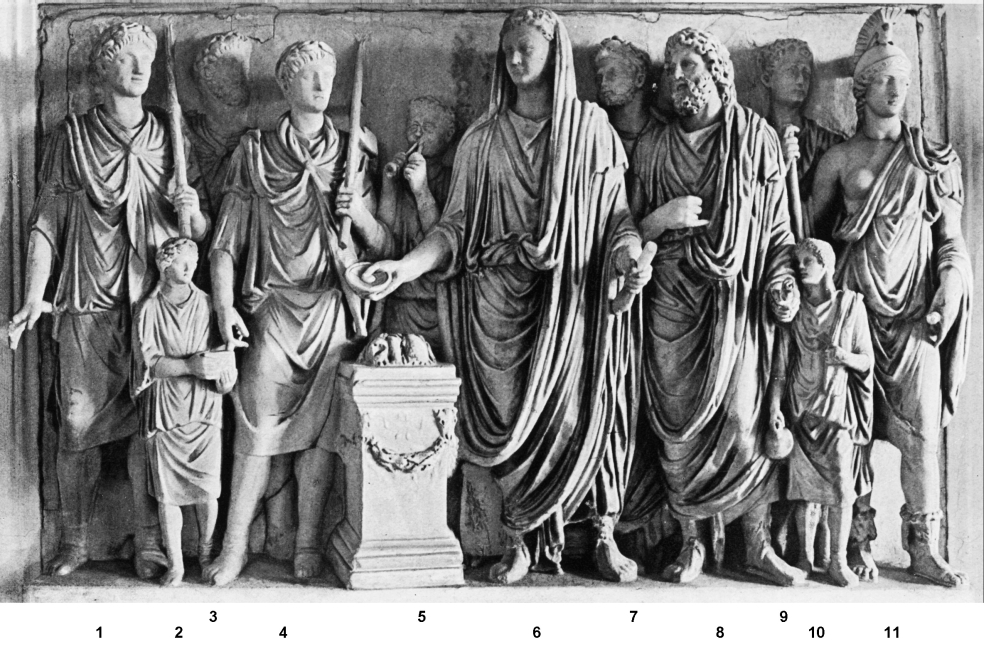

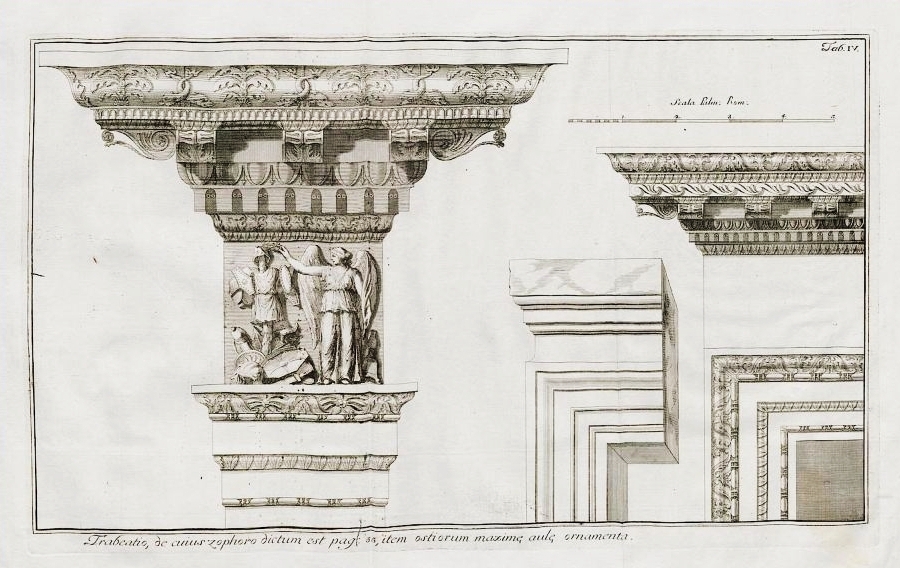

Fig. 36. The Nollekens Relief, on display above the fire

place in the White Hall of the Gatchina Palace near St. Petersburg, marble, 88

x 139 cm. F.

Bianchini (1738, 68) found this

relief in 1722 in the `Aula Regia´ of

Domitian's `Domus Flavia´; cf. S.

Cosmo (1990, 837 Fig. 8 [= here Fig.

39]). J. Pollini (2017b, 120,

124; cf. p. 98, Fig. 1) suggests that it

shows the togate triumphator

Domitian, sacrificing in AD 89 just outside Domitian's Porta Triumphalis; after which, the Emperor would begin his (last)

triumphal procession. Photograph, taken in 1914, when the relief was still

preserved in its restored state of the 18th century. Courtesy John Pollini.

The caption of

Pollini's Fig. 1 reads: "Photograph taken in 1914 of the Nollekens Relief

... [the author provides a reference for that on p. 107 with n. 47]. Note that

only the heads of nos. 6 [i.e., of Domitian], 8 [i.e., of the Genius Senatus] and 10 [i.e., of a boy

ministrant] in the foreground and of all the background figures are ancient [my

emphasis]".

Pollini (2017b, 97)

begins his article as follows:

"Mainstream

classical scholarship has long considered as lost a Roman ``historical´´ relief, excavated in the earlier part of the

18th c.[entury] in the Palace of Domitian on the Palatine hill [with n. 1].

Showing an emperor sacrificing, it is known as the Nollekens Relief after Joseph

Nollekens, an accomplished British sculptor who came to possess it in the 18th

c.[entury]. Besides being a sculptor and painter, he was a sculptural restorer

and dealer active between 1761 and 1770 in Rome [with n. 2], where he worked in

the workshops of the sculptural restorer Bartholomeo Cavaceppi and in his own

studio [with n. 3]. The relief has been known chiefly from two engravings and a

pen-and-watercolor drawing, all produced in the 18th c.[entury], but rather

than being lost the relief has been hiding in plain sight in the Gatchina

Palace near St. Petersburg [where it has been continuously on display since the

1770s/ early 1780s]".

In his notes 1-3,

Pollini provides references and further discussion.

Concerning the

sculptural decoration of Domitian's `Aula

Regia´ at the `Domus Flavia´ on

the Palatine, Pollini (2017b) is able to make an important contribution by

presenting in great detail the so-called Nollekens Relief, which was found

there by Francesco Bianchini in 1722 (cf. id.

1738, 68, quoted verbatim infra) - a

fact which Pollini himself ignores though. As Pollini is able to demonstrate,

already in the later 18th century the relief had allegedly disappeared. Silvano

Cosmo (1990, 837, cf. his plan Fig. 8 =

here Fig. 39) has found out

and documented in plan where exactly within Domitian's Palace Bianchini had

`excavated´. - To this I will come back below (cf. infra, in Chapter V.1.i.3.b); Section II.).

The Nollekens Relief

was previously only known from non-photographic images of the 18th century,

which Pollini (2017b, Figs. 2-4) also illustrates and discusses, whereas he is

first to publish photographs of the Nollekens Relief (cf. J. POLLINI 2017b,

Frontispiece, and Figs. 1; 10-12; 16). Among those, one is especially important

(his Fig. 1 = here Fig. 36), because

it was taken in 1914, when the portrait head of Domitian, appearing on this

relief (cf. figure 6), was still

preserved; this head is now lost. The relief itself, possibly broken into six

fragments when found, had been restored in the 18th century, and was greatly

damaged in World War II and after that. Pollini was also able to find out that

a plaster cast of the relief had been produced when it was in Russia, but the

whereabouts of the cast is unknown.

Pollini (2017b) has

meticulously traced the vicissitudes of the relief summarized above (here Fig. 36) since its `excavation´ and its alleged disappearance soon

afterwards. Gerhard Koeppel (1984, 65; cf. id.

1985, 146, n. 20) was told that the relief has been on display since the 18th

century at the Gatchina Palace near St. Petersburg. After Koeppel's first

discussion of the relief (1984), "O. Neveroff" kindly informed him

that the relief was by no means lost, but instead on display in this

collection, as Koeppel reported. In the course of his correspondence with his

Russian colleagues, Koeppel had also received two photographs of the relief

from them, and mentioned this fact also in his "Nachtrag" (1984, 65;

cf. id. 1985, 146, n. 20). But

Koeppel himself never published those photographs, and even his information

that the relief had been in the Gatchina Palace since the 18th century has been

neglected by almost all subsequent scholars. Cf. Pollini (2017b, 97, n. 1, pp.

106-107 with ns. 43-46, who quotes G. KOEPPEL 1984, 46-49, 65; id. 1985, 146, n. 20).

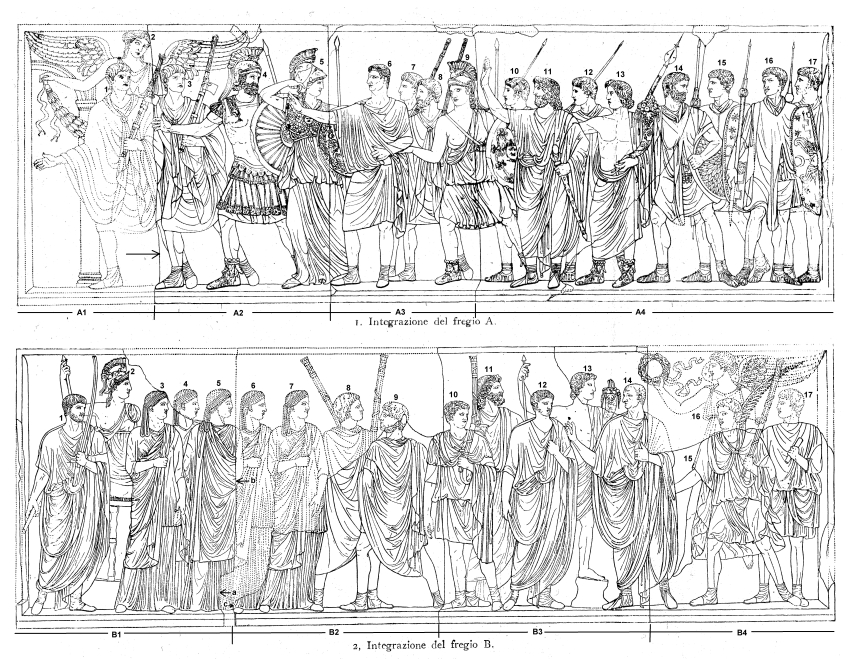

Pollini (2017b, 115-118) provides detailed comparisons

of the Nollekens Relief relief with the Cancelleria Reliefs (cf. here Figs. 1;

2; Figs. 1 and 2 drawing). His observations refer to many subjects which are of

interest in this study, which is why they have already been quoted several

times above (cf. especially supra, in

Chapter II.3.1.d); Section I., and infra, at Appendix IV.c.1.)).

Francesco Bianchini found the Nollekens Relief in 1722,

while `excavating´ in the Orti Farnesiani, and precisely within Domitian's

Palace on the Palatine. As usual with such early finds, it is crucial to

clarify 1.) to exactly which area an

`excavator´ at a given time may have had access; and 2.) within which ancient building this `excavation´ was conducted.

According to Silvano

Cosmo's plan (in his article: "Aspetti topologici e topografici degli Orti

farnesiani come premessa alla conservazione ambientale" 1990, Fig. 8 [=

here Fig. 39]), who has successfully undertaken both kinds of research in order

to draw this plan, Bianchini `excavated´ exclusively within the `Aula Regia´ and the immediately

adjacents halls called `Basilica´ and

`Lararium´, all three located within

the `Domus Flavia´ (cf. supra, in Chapter II.3.1.d); Section I.).

Since on 25th, 26th

February, 3rd and 4th March 2020 I have been given access to Bianchini's book

(1738) in the Library of the British School at Rome, I could verify Cosmo's

cartographic information, given on his Fig. 8: he marks on his plan the areas,

where precisely Francesco Bianchini and Pietro Rosa had excavated; cf. his

labels: "scavi p. rosa 1861-64; scavi f. bianchini 1720-26". By

reading now Bianchini's book (1738, 50, 68, quoted verbatim infra, at Chapter V.1.i.3.b);

Section III.) myself, I

realized that he describes explicitly that he `excavated´ within these three

halls, and that he found the Nollekens Relief (his Tab. VI.; cf. here Fig. 36; cf. his plans Tab. II. and

VIII. = both here Fig. 8)) in that

hall within the `Domus Flavia´, which

was already then (and is still now) called `Aula

Regia´.

Fig. 39. S. Cosmo's plan of the (former) Orti Farnesiani

on the Palatine in Rome. From S. Cosmo: "Aspetti topologici e topografici

degli Orti farnesiani come premessa alla conservazione ambientale" (1990, 837,

Fig. 8). The caption of his figure reads: "Il giardino di Napoleone III

(1861 - 1870) Dis.[egno]

S. Cosmo".

Cosmo

marks on this plan the areas, where exactly within the Orti Farnesiani

Francesco Bianchini and Pietro Rosa had excavated, see his labels: scavi p.

rosa 1861-64; scavi f. bianchini 1720-26. Cosmo marks also the boundary between

the Orti Farnesiani on the Palatine and the adjacent property to the

south-west, which at Bianchini's time

had been the property of the "Conti Spada", as Bianchini (1738, see

the lettering on his plan Tab. VIII = here Fig. 8) had also himself indicated

on his plan.

Cosmo has documented the consecutive owners of this

property. See the letterings on his plan: spada 1689-1746 / p. magni 1746-1776

/ rancoureil 1776-1816 / c. mills 1816-1849 / smith 1849-1856 /suore della

visitazione 1856.

Pollini (2017b, 101-102, 113, 124), who has overlooked

Cosmo's account, (erroneously) suggests that Bianchini found the Nollekens

Relief elsewhere within the Domus

Augustana, but where Bianchini had certainly not `excavated´. - To all this I will come back below (cf. infra, at Chapter V.1.i.3.b); Section II.).

As will be quoted in

detail in the following, Pollini provides a thorough analysis of the scene

represented on the Nollekens Relief (Fig.

36): the togate triumphator

Domitian, who is depicted as sacrificing at an altar, accompanied by the Dea Roma, the Genius Senatus, the two consules,

two of his lictors and one soldier, a tibicen,

and interestingly also by two "young sacrificial attendants, ministri ... paedagogiani (servile

pages)" from his own household; cf. Pollini (2017b, 113).

When I sent this Chapter to Rose Mary Sheldon, asking her

to revise my English, I had added at this point:

[I need to check,

whether Domitian himself was possibly himself consul in AD 89! - meant as a explanation

to Rose Mary that I still needed to do this]. Rose Mary was kind enough to

answer this question for me by E-mail, adding the following remark:

"Domitian was

consul every year of his reign except 89, 91, 93, 94 and 96. Pat Southern

[1997], Domitian, p. 35". - See also Dietmar Kienast, Werner Eck, Matthäus

Heil (2017, 110): from AD 70-95, Domitian held the consulship 17 times (!).

As we shall see below,

Pollini (2017b, 120 with n. 106; cf. infra,

at Chapter V.1.i.3.b); Section IV.) suggests that the Nollekens Relief

shows Domitian sacrificing in AD 89. Pollini himself has not realized that,

because of the representation of both consules

(figures 7 and 9) on the Nollekens Relief, this is in theory actually possible,

because - as we have seen above - in that year Domitian did not himself hold one of the consulships. To

this I will come back below (cf. infra,

at Chapter VI.3. Addition: My own tentative suggestion, to which monument or building

the Cancelleria Reliefs may have belonged, and a discussion of their possible

date).

The Emperor Domitian

[on the Nollekens Relief] is crowned with a laurel wreath, and the fasces of his two paludate lictors (with

axes attached to their rods !) are likewise adorned with laurels. Pollini,

therefore, convincingly suggests that Domitian is shown in the course of

performing this sacrifice just outside the Porta

Triumphalis, that was built anew by the emperor, and that immediately after

that will begin Domitian's triumphal procession. In Pollini's opinion (2017b,

120 with n. 106, referring to Suet., Dom.

6,1), the sacrifice depicted on the Nollekens Relief, must refer to Domitian's

last triumph of AD 89 (for that; cf. supra,

n. 232,

in Chapter I.2., and infra, at Chapter VI.3.; Addition: My own

tentative suggestion, to which monument or building the Cancelleria Reliefs may

have belonged, and a discussion of their possible date). Pollini also

suggests, where in reality Domitian has conducted this sacrifice, which is

represented on the Nollekens Relief. - To this I will come back below (cf. infra, at Chapter V.1.i.3.b); Section IV.).

Already Diana E.E.

Kleiner (1992, 183) wrote about this panel: "Also from Domitian's Palace

is the so-called Nollekens Relief, which was found east of the state dining

hall, the Coenatio Jovis. It is today lost and known only through drawings (for

example, fig. 153), but it appears to have been manufactured while Domitian was

emperor. It depicts a sacrifice that is in the tradition of earlier sacrifice

scenes such as those in the Louvre Suovetaurilia Relief (see fig. 117 [cf. here

Fig. 25]), but with two noticeable

differences. The figures of the sacrificant - probably the emperor - and his

companions are almost frontal, and the human emperor interacts with divinities

and personifications (Roma or Virtus and the Genius Senatus); such interactions

would become one of the hallmarks of Domitianic art". - The latter is for

example true of Frieze A of the Cancelleria Reliefs (cf. supra, at Chapter I.2., and here Fig. 1; Figs. 1

and 2 drawing), and Kleiner's observed frontality of the figures on the

Nollekens Relief is also true of the relief from Domitian's Templum Gentis Flaviae, which depicts

Vespasian's adventus into Rome in AD

70 (cf. supra, at Chapter V.1.i.3.a) and here Fig. 33).

To Kleiner's "Coenatio

Jovis" (also referred to as: Cenatio

Iovis; Triclinium (cf. here Figs. 8;

8.1, label: "TRICLINIUM"; Fig.

58, label: "TRICLINIUM"; Figs.

108-110); and Banquet hall), I will come back below (cf. infra, in Chapter V.1.i.3.b); Section II.).

Pollini

(2017b, 101) writes: "we know that the

reliefs were found in the general vicinity of the Aula Regia in the Domus

Flavia (fig. 6) ... the excavations were ``within the Farnese Gardens´´,

created in 1550 by Alessandro Farnese on the N[orth] side of the Palatine,

where indeed part of Domitian's Palace is located [with n. 12, providing a

reference; my emphasis]". - With "the reliefs", Pollini refers

to the Nollekens Relief (i.e., F.

BIANCHINI 1738, Tab. VI.; cf. here Fig.

36) and to another one, found by Bianchini together with it (cf. J. POLLINI

2017b, 104-105, his Fig. 5 = F. BIANCHINI 1738, Tab. VII. = here Fig. 37); this relief is obviously now

lost.

Fig. 37. The other fragmentary marble relief, found by

Francesco Bianchini in 1722 within the `Aula

Regia´ of the `Domus Flavia´,

shows four female representations or divinities in Greek dress. From F.

Bianchini (1738) Tab. VII.: "Fragmentum anaglyphi repertum in Palatio

Caesarum intra Hortos Farnesianos MDCCXXII Hieronymus Rossi incid.". Cf. infra, at ChapterV.1.i.3.b); Section III.

Cf. Pollini (2017b,

120): the emperor, depicted on the Nollekens Relief (cf. here Fig. 36: figure 6), is Domitian. Cf. p. 124: the represented sacrifice

"would allude to the sacrifice performed at the Porta Triumphalis, thereby

recalling triumph" (for a more detailed quotation of this passage; cf. infra, at Appendix IV.c.1.)).

Cf. Pollini (2017b,

97-99): the Nollekens Relief is on display in the White Hall of the Gatchina

Palace near St. Petersburg (cf. his Figs. 10; 11). Cf. pp. 97-99: in this

article, Pollini "examines the history of this relief, its discovery and

restoration in the 18th c.[entury], its purchase by the Russian noble Ivanovich

Shuvalov, and its vicissitudes during World War II and afterwards. Also

presented and discussed is the evidence for the condition of the relief in 1914

and subsequently. The 1914 photograph (fig. 1, with my numbering of figures [=

here Fig. 36]) allows us to compare

it with the three earlier non-photographic illustrations (figs. 2-4) in order

to address questions about restoration and other details of [page 99] it. The

history of the relief and its supposed disappearance in the later part of the

18th century are important for the history of collecting and the display of

classical antiquities".

After having finished

writing this Chapter, I received on

22nd April 2020 Paolo Liverani's forthcoming essay ("Historical reliefs

and architecture") that has in 2021 appeared in the essay volume, edited

by Aurora Raimondi Cominesi et al.

(2021), and on 30th April 2020, Liverani has kindly granted me the permission

to quote verbatim from this text.

Concerning the Nollekens Relief, Liverani (2021, 88) writes:

"Another

interesting document is the so-called Nollekens Relief, representing an

imperial sacrifice (fig. 4), [with n. 21] ... In the middle Domitian is shown

sacrificing on a little altar, to the right is the Genius of the Roman Senate

and the personification of Rome with a young assistant for the sacrifice (camillus). To the left are two lictors

carrying the fasces with axes, a flute player and a second camillus. Pollini, who

rediscovered the lost relief, interprets

the scene in connection with the triumph and considers it as the sacrifice

performed by the Emperor in front of the Porta Triumphalis before entering the

city. Setting aside some minor problem of his reconstruction connected wit this

gate, [with note 22] the triumphal

connotation is based on weak evidence and must remain hypothetical. What

appears interesting is the survival of Domitian's portrait in the imperial

palace on the Palatine after his damnatio

memoriae, but, unfortunately, we do not know the exact find spot and cannot

solve the riddle [my emphasis]".

In his note 21,

Liverani writes: "Pollini 2017 ... [i.e.,

here J. POLLINI 2017b]".

In his note 22,

he writes: "Pollini seems to be not aware of the discussion about the

position of the Porta Triumphalis after the extension of the pomerial

limits". - For a discussion of this subject; cf. infra, at Chapter V.1.i.3.b);

Section IV.

Liverani (2021, 88)

identifies the represented figures on the Nollekens Relief exactly like Pollini

(2017b) himself, but he leaves out the figures in the background (cf. here Fig. 36: figure 3, a soldier, and figures

7 and 9, two togate men), whom

Pollini, in my opinion convincingly, interprets as the consules.

And because we have seen above that in AD 89 Domitian

did not himself hold one of the consulships, the appearance of the two consules on the Nollekens Relief

supports at the same time Pollini's suggested date for the scene depicted on

the Nollekens Relief: AD 89 (!).

Even so, it is interesting that Liverani has not realized

that the figures, which he has

mentioned, are positioned according to strict observations of their relevant

spatial restrictions: the right-hand half of the relief represents the area domi (with the Dea Roma and the Genius

Senatus, figures who, according to their relevant constructions, are

constrained to remain within the pomerium

of Rome; not by chance the consules

appear on that side of the relief), the left-hand half of the relief represents

the area militiae instead (here we

see the two paludate lictors, having axes attached to heir rods, their fasces are adorned with laurels, as well

as one soldier). - The soldier is, of course, of special importance, when we

try to find out, what the scene might represent. For a detailed description of

the two lictors and the soldier; cf. Pollini (2017b, 115, quoted verbatim infra, at Chapter V.1.i.3.b); Section III.).

In the following, I

repeat what was already written above (cf. supra,

at Chapter I.2.1.c):

`It is interesting to

compare in the just discussed context the solution, found by the artists who

designed the Nollekens Relief (cf. ... here Fig. 36). Here the two paludate lictors, who accompany Domitian,

and one soldier (figures 1, 4 and 3) represent the area militiae. All three of them are standing

just outside the pomerium and appear

on the left hand `half´ of the panel - as they should. Whereas those figures,

who represent the area domi: the Dea Roma, the Genius Senatus and the two consules

(figures 11, 8, 7 and 9) are standing on the `right´ hand

half of the panel - as also they should. The emperor himself thus stands at the

pomerium-line - as he likewise

should, provided we follow Pollini's interpretation. According to his

hypothesis, Domitian is performing the sacrifice at (or in front of) the Porta Triumphalis. Only after its

completion, Domitian will transgress the pomerium-line

(by passing through his newly built Porta

Triumphalis), and thus begin his triumphal procession, accompanied by his

army and his lictors, who, at the represented moment, are still waiting outside

the pomerium. And, as soon as the

procession will have marched through the Porta

Triumphalis, it will be solemnly received by the entire populace of Rome,

indicated by the city's representatives on the right hand `half´ of the

relief.´

Domitian thus stands on

the Nollekens Relief at the pomerium-line.

This the artists, who created the relief, have shown by the distribution of the

figures (apart from the two boy ministrants and the flute player) who surround

the emperor. In addition to this, Domitian is wearing a toga, is crowned with a laurel wreath, and is shown in the act of

sacrificing. And because I believe (because of the presence of the two consules) that Pollini is right in

suggesting that the scene, visible on the Nollekens Relief, shows an event of

AD 89, I therefore wonder what else

this panel could represent, than what Pollini (2017b) himself suggests.

In addition to the

above-mentioned details of the Nollekens Relief itself, which Liverani (2021)

has not considered in his reasoning, he ignores the fact that Francesco

Bianchini (1738, 68) found the Nollekens Relief within the `Aula Regia´ (cf. infra, at Chapter V.1.i.3.b); Section II.). And because Bianchini documented in great detail the marble

decoration of this hall (cf. F. BIANCHINI 1738, Tab. III.; IV. = here Fig. 9; cf. infra, at Chapter V.1.i.3.b); Section III.), we know also that the major theme of the `Aula Regia´ was the celebration of

Domitian's military victories, cf. Eugenio Polito (2009, 506, quoted verbatim infra, at Chapter V.1.i.3.b); Section III.).

To conclude. Pollini's (2017b)

himself ignores the fact that the Nollekens Relief was actually found within

the `Aula Regia´. Considering not

only what was said above about the iconography of the Nollekens Relief itself,

but also that the overall theme of this magnificent hall was the praise of

Domitian's military victories, which the emperor had celebrated with triumphs,

I therefore maintain my earlier judgement. Namely that Pollini's interpretation

of the Nollekens Relief, according to which it shows Domitian sacrificing in AD

89 at the Porta Triumphalis before

beginning his (last) triumphal procession, is sound.

Before discussing in the following Section, where

Francesco Bianchini `excavated´ the Nollekens Relief, I allow myself a digression on the `excavator´, Francesco

Bianchini.

Paolo Liverani (2000, 67) has characterized Francesco Bianchini as

follows:

"Dopo un secolo e

mezzo Clemente XI Albani (1700-21) torna a interessarsi alle antichità e nel

1703 nomina mons.[ignore] Francesco Bianchini Commissario alle Antichità di

Roma. Si tratta di un uomo i cui interessi abbracciano matematica, astronomia e

archeologia e con una vasta rete di conoscenze in tutta Europa. Costui

allestisce il «Museo Ecclesiastico», un esperimento di breve vita che durerà

solo fino al 1716, ma di grande valore [with n. 14]. Il criterio con cui

vengono scelti i materiali è di carattere filologico e storico, senza nessuna

concessione estetica. Vengono privilegiati i documenti iscritti che abbiano

rilevanza cronologica (per es.[empio] le iscrizioni consolari), senza limitarsi

all'antichità, ma comprendendo anche documenti medievali con una modernità di

visione assolutamente stupefacente".

In his note 14,

Liverani writes: "C. Hülsen, Il «Museo Ecclesiastico» di Clemente XI

Albani, BullCom 1890, 260-77; Pietrangeli, cit. a nota precedente [= C.

Pietrangeli, I Musei Vaticani. Cinque secoli di storia (1986) 3-27]; F.

Uglietti, Un erudito veronese alle soglie del Settecento, Mons. Francesco

Bianchini 1662-1729 (1986) 61-63; C. M. S. Johns, Papal Art and Cultural

Politics. Rome in thè Age of Clemens XI (1993) 33-8".

ChapterV.1.i.3.b); Section II.

The Nollekens Relief was found in the `Aula Regia´ within the `Domus Flavia´

In order to be able to

understand the following discussion of the topography of Domitian's Palace on

the Palatine, I suggest that the reader consults all relevant maps

simultaneously.

Cf. here Figs. 58; 71; 73, labels: PALATIUM;

Arch of DIVUS TITUS; VICUS APOLLINIS ?/ "CLIVUS PALATINUS"; ARCUS

DOMITIANI / DIVI VESPASIANI ?; Temple of IUPPITER INVICTUS ? or of : IUPPITER

STATOR ? IUPPITER VICTOR ? IUPPITER PROPUGNATOR ?; "DOMUS FLAVIA";

"BASILICA"; "AULA REGIA"; "LARARIUM";

"PERISTYLE"; "TRICLINIUM"; DOMUS AUGUSTANA; "Porta

principale"; Arch of DOMITIAN ?; Cancelleria Reliefs ?; Vigna Barberini;

DI(aeta) (a)DONAEA; site of Nero's CENATIO ROTUNDA; S. Sebastiano; "AEDES

ORCI"; SOL INVICTUS ELAGABALUS; IUPPITER ULTOR; CURIAE VETERES?". -

For those toponyms; cf. infra, at Appendix V.; Sections IV. and VII.

See also Silvano

Cosmo's plan of the Orti Farnesiani (1990, 837, Fig. 8 = here Fig. 39); Francesco Bianchini's plan

(1738, his Tab. VIII. = here Fig. 8)

of Domitian's Palace on the Palatine (online at: <https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/bianchini1738/0001/image>); the map SAR 1985, labels: 64: Domus

Flavia: "Basilica"; 65:

Domus Flavia: "Aula Regia"; 66: Domus Flavia: "Lararium" (the relevant detail of this map is reproduced in: LTUR IV [1999] fig. 6, s.v. Palatium, but without the numbering

of the single structures); Amanda Claridge's plan of the Imperial Palace (1998,

132-133, Fig. 54, p. 135, p. 137, Fig. 57: "Domitian's Palace.

Reconstruction of the great Banquet Hall and its fountain courts"; ead. 2010, 145-156, esp. pp. 146-147,

Fig. 55, p. 148): "`Aula Regia´ or Audience Chamber", p. 150, Fig.

57: "Domitian's Palace. Reconstruction of the great Banquet Hall and its

fountain courts"; Filippo Coarelli (2012, 2-3, Fig. 1 [= SAR 1985], p. 116, Fig. 29, p. 447, Fig.

88; and the plan published by John Pollini (2017b, 101, Fig. 6): "Plan of

Domitian's palace (R. Mar ... [i.e.,

here R. MAR 2009] fig. 3, slightly altered by author)", in which the `Aula Regia´ is labelled: "Salón de

trono", the `Basilica´:

"Bas.", the `Lararium´:

"Lar.", the entrance to those three halls in the west:

"Ingreso", and the larger entrance to the `Aula Regia´ in the north: "Ingreso ceremonial". Pollini's

just-mentioned `slight alteration´ in Mar's plan (2009, Fig. 3) of Domitian's

Palace consists in the fact that he

marks the small hall immediately to the east of the `Aula Regia´ with the

lettering: "Lar.[arium]"; and Daniela Bruno ("Region X. Palatium", 2017, ill. 13 Palatium, domus Augustiana, AD 117-138:

Reconstruction by D. Bruno, illustration by inklink").

The most recent publications on Domitian's Palace on the

Palatine, those by Ulrike Wulf-Rheidt (2020), Natascha Sojc (2021), Aurora

Raimondi Cominesi and Claire Stocks (2021), and Aurora Raimondi Cominesi (2022)

are discussed supra, in the Chapters The major results of this book on Domitian;

and at The visualization of the results

of this book on Domitian on our maps.

This leads us to one of

the problems that are connected with Domitian's Palace on the Palatine : the

parts discussed here, of which the Palace consists, are unfortunately not called by all modern commentators by

the same (modern) names. From Francesco Bianchini's (1738) account and his own

plan (his Tab. II; cf. here Fig. 8),

to be discussed below, it is clear that he excavated at the `Basilica´, `Aula Regia´ and `Lararium´

of the `Domus Flavia´. I follow with

this nomenclature of those halls Bianchini (cf. here Fig. 8), which is repeated on the map SAR 1985 (cf. supra). But

note that Bianchini (1738, caption of his Tab. III., quoted verbatim infra) erroneously believed

that the Domitianic Palace, excavated by him, should be identified with the

`Domus Tiberiana´. In Cosmo's plan (cf. here Fig. 39) the area, where Bianchini excavated, is correctly

indicated. Ricardo Mar (2009, 256, Fig. 3: label: "Larario", p. 257,

Fig. 4, label: "Larario/Tempio") calls another part of the Palace `Lararium´, namely the large eastern peristyle.

As we shall see in the following, Pollini (2017b, 103) refers to this structure

erroneously as to the "``Adonea Peristyle´´". - To the real

`Adonisgarden´ in Domitian's Palace I will come back below.

When discussing with Amanda Claridge the research

presented here back in 2020, I asked her for advice concerning reconstructions

of Domitian's Palace on the Palatine.

Because at that time I knew only Sheila Gibson's

reconstruction drawing of the `Triclinium´/

`Coenatio Iovis´/ Banquet Hall,

published by Amanda in her Rome guide; cf. Claridge (1998, 137, Fig. 57; ead. 2010, 150, Fig. 57:

"Domitian's Palace. Reconstruction of the great Banquet Hall and its

fountain courts"), Peter Connolly's (8th May 1935 - 2nd May 2012) coloured

reconstruction drawing; cf. Peter Connolly and Hazel Dodge (1998, illustration

on pp. 222-223, figure without number. Its caption reads: "Ein Querschnitt

durch die rekonstruierte Aula Regia, das Peristyl und triclinium der Domus Flavia. Das Dach der Aula Regia wird heute von

Experten viel diskutiert - hier wurde es aus Holz rekonstruiert"), and the

illustration, published by Daniela Bruno (2017, ill. 13: "Palatium, domus Augustiana, AD

117-138", "Reconstruction by D. Bruno, illustration by

inklink"), into none of which the architectural marbles, found within

these Halls of Domitian's Palace have been integrated.

Interestingly, of Connolly's just-mentioned coloured

reconstruction drawing exists now a version that shows the same image `back to

front´; cf. Aurora Raimondi Cominesi and Claire Stocks (2021, 106, Fig. 2:

"Reconstruction of the Domus Flavia on the Palatine (akg-images / Peter

Connolly))".

This is recognizable, when we compare with this image the

true locations of the `Basilica´, `Aula Regia´, `Peristyle´ and `Triclinium´/

`Coenatio Iovis´ / Banquet Hall on

any plan of Domitian's Palace; cf. for example in Natascha Sojc (2021, 132,

Fig. 2) and here Figs. 8.1; 58.

In the following, I

repeat a passage, written for the

Chapter Introductory remarks and

acknowledgements:

In the course of this

discussion, Amanda Claridge was kind enough to alert me to `the reconstruction

drawings [of Domitian's Palace on the Palatine] (here Figs. 108-110) of the architect Gordon Leith (1885-1965 [whose name

Amanda at first did not remember, nor the date of his scholarship]) from South

Africa, who had in 1913 a scholarship at the British School at Rome. As Amanda

would later confirm ... Gordon Leith had only received a scholarship for one

academic year (i.e., from October

until June ... Amanda ... had seen his drawings at the British School, where

they had been on display, and which, as she recalled, in the 1980s or 1990s had

been donated to the Superintendency of the State on the Palatine.

At that stage of our discusssion it seemed impossible to

trace the architect and his drawings. I myself, although having spent much time

at the BSR since late December of 1980, did not remember these drawings, which

is why, without Amanda's help, I would never have been able to identify them

(!).

The reason being that neither the name of this man, nor the

time of his scholarship at the British School were known, and that although

Valerie Scott, the Librarian of the BSR, and the archivist Alessandra Giovenco

had supported Amanda's relevant research in all possible ways. In the end,

Amanda found out by chance that, already a long time ago, four of those

drawings have been published by Maria Antonietta Tomei ("Scavi Francesi

sul Palatino : le indagini di Pietro Rosa per Napoleone III (1861-1870)",

École française de Rome 1999, figs 225, 228, 229, and 230). But Amanda told me

also that she knew that Gordon Leith had created many more of these drawings.

My thanks are due to Francesca Deli, Assistant Librarian of the BSR, for

scanning for me in Tomei's publication Gordon Leith's extraordinary

reconstruction drawings of Domitian's Palace on the Palatine (cf. here Figs. 108-110)´.

Figs. 108-110 (when you klick on these thumbnails you will see the original size of the illustrations)

See the Contribution by Amanda Claridge in this

volume: A note for Chrystina Häuber:

Drawings of the interior order of the Aula Regia of the Palace of Domitian on

the Palatine, once in the British School at Rome.

Why I am telling you all this at the beginning of this

Chapter? Because we shall look below at Francesco Bianchini's (1738)

documentation of architectural marbles from the `Aula Regia´, and will hear the judgements of recent scholars

concerning the sculptural decoration of this hall. We shall also realize that

Gordon Leith, with his reconstruction drawings of Domitian's Palace (here Figs.

108-110), has provided a very interesting contribution to this discussion; cf. infra, at ChapterV.1.i.3.b); Section III.

All this information taken together, so my hope, may be

useful for new efforts to reconstruct the interior order of the `Aula Regia´. Contrary to Bianchini's own

reconstruction of the `Aula Regia´

(cf. id. 1738, his Tab. II. = here Fig. 8) and to Gordon Leith's

reconstruction of the `Aula Regia´

(1913; here Fig. 108), in both of

which the interior order of this hall has only one colonnade, we know now that

there was also a second order, because "columns in front of the niches [in

the `Aula Regia´] ... were surmounted

by further colonnades, taking the ceiling about 30 m (100 RF [i.e., Roman Feet]) above the

floor"; cf. Amanda Claridge (1998, 135; ead. 2010, 148). Peter Connolly; cf. Connolly and Dodge (1998,

illustration on pp. 222-223) had already considered this information in his

reconstruction; and of course also Daniela Bruno (2017, ill. 13).

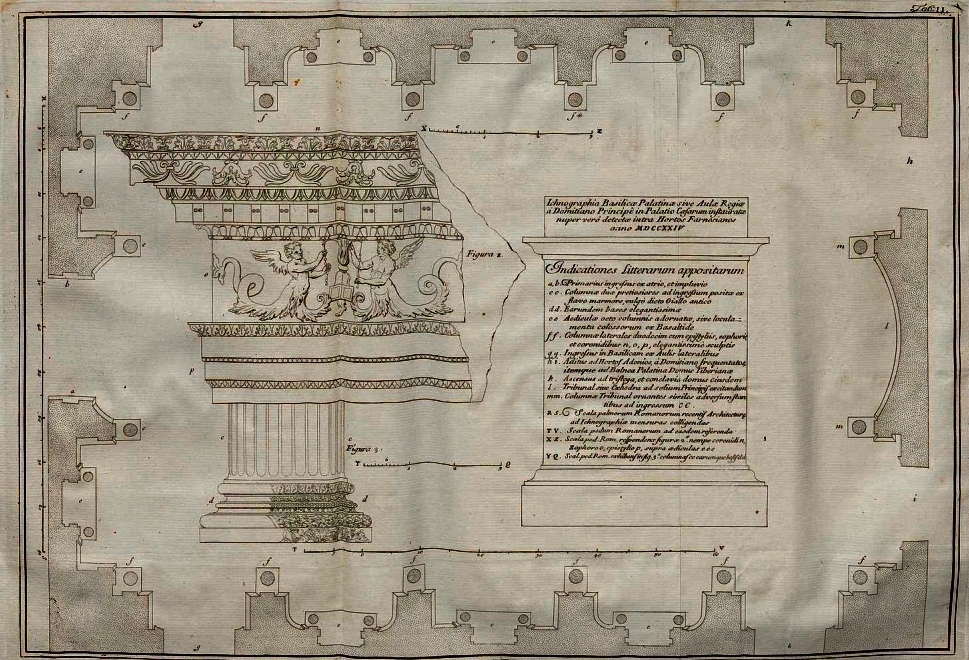

Bianchini (1738, Tab. II = here Fig. 8) shows in the middle of his measured ground-plan of the `Aula Regia´ a reconstruction of the

colonnade of the interior order, using for this reconstruction precisely drawn

architectural fragments that were found within the `Aula Regia´. But because Bianchini does not explain this

reconstruction in his text, it is impossible to know, from this etching alone,

whether the relevant parts of this reconstruction: column base, column shaft

and architrave, had actually belonged together.

Even if that had been the case, it is for us likewise impossible to know,

whether Bianchini's reconstruction belonged to the lower or rather to the upper

colonnade of the interior order of the `Aula

Regia´. - Provided it is true, what all three: Sheila Gibson in her

reconstruction of the interior order of the `Triclinium´/ `Coenatio Iovis´/

Banquet Hall; cf. Claridge (1998, 137, Fig. 57; ead. 2010, 150, Fig. 57), and Peter Connolly and Daniela Bruno in

their reconstructions of the interior order of the `Aula Regia´ have assumed : namely that in both halls the columns of

both superimposed colonnades had (almost, or even exactly) the same heights

(!); cf. Connolly and Dodge (1998, illustration on pp. 222-223); and Bruno

(2017, ill. 13).

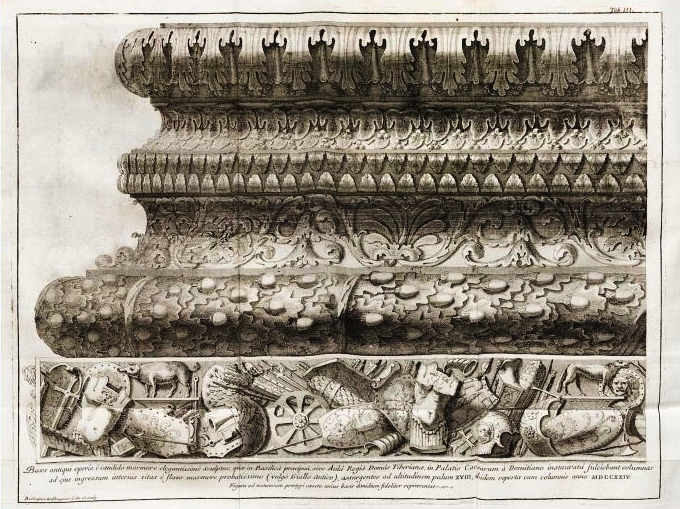

In ChapterV.1.i.3.b);

Section III., we will, in addition to

this, learn from François de Polignac (2009, 507) that of the interior order of

the `Aula Regia´ some fragments are

still preserved of the architraves of the first order, the lower colonnade and

of the second, superimposed order, both of which were decorated with friezes

showing "peopled scrolls", of which Polignac is able to illustrate

one badly damaged fragment. Unfortunately, Polignac (2009, 507) does not

discuss Bianchini's (1738, Tab. II; here Fig.

8) just-mentioned reconstruction in this context.

By reading Polignac's text, it seems nevertheless to be

obvious that one of Polignac's (2009, 507) colonnades of the interior order of

the `Aula Regia´ is precisely that,

which also Bianchini (1738, Tab. II = here Fig.

8) has reconstructed. And one thing is definitely clear: Gordon Leith

(1913) has integrated exactly the same fragments of those architraves with

"peopled scrolls" of both orders, and/ or the reconstruction drawings

of the frieze of the first order, mentioned by Polignac (2009), into one of his

own reconstruction drawings. But Leith has not integrated his resulting

reconstruction of this architrave into his drawing of the `Aula Regia´, where the fragments of both friezes with "peopled

scolls" were actually found, but instead into his reconstruction drawing

of the `Triclinium´ (cf. here Fig. 110) (!).

After having already

anticipated these results, let's approach this complex subject in the following

together, step by step.

For the following

discussion; cf. here Figs. 58; 73,

labels: PALATIUM; "DOMUS FLAVIA"; "BASILICA"; "AULA

REGIA"; "LARARIUM"; "PERISTYLE";

"TRICLINIUM".

Pollini (2017b, 101-103, in his Section: "Bianchini and the place of discovery"

[i.e.,

of the Nollekens Relief, and of the

other relief; cf. here Figs. 36; 37]) writes:

"From Bianchini's

discussion of the location of his excavations, we know that the reliefs were

found in the general vicinity of the Aula Regia in the Domus Flavia (fig.

6)". He also mentions the collossal basalt statues of Hercules and

Bacchus/Dionysus with Pan (now in Parma's Galleria Nazionale) that once

decorated niches in the Aula Regia [with n. 11]. He indicates that the

excavations were ``within the Farnese Gardens´´, created in 1550 by cardinal

Alessandro Farnese on the N[orth] side of the Palatine, where indeed part of

Domitian's Palace is located [with n. 12]. This

is further confirmed by the captions to the plates (VI-VII) illustrating both

reliefs [with n. 13]. Both were

probably found in or near the Horti

Adonii or Adonea, in an area that

separates the ``private sector´´ (Domus Augustana) from the ``state sector´´

(Domus Flavia) of the palace, and just northeast of the grand triclinium of the latter [with n.

14]. This garden peristyle appears to

[page 102] refer to the area just

southeast of the Aula Regia, still within the Farnese Gardens, and facing those

of the Villa Spada, so designated by Bianchini in the 1738 publication

[with n. 15]. The Villa Spada, formerly known as the Villa Mattei, later became

the Villa Mills and is shown on P. Rosa's 1868 plan (fig. 7). Rosa excavated and re-excavated where

Bianchini had dug, marked on the former's plan by the dark areas along the E[east]

edge of the ``state sector´´. On that

plan my dotted ellipse marks the general area in which Bianchini indicates the

two [page 103] reliefs were found.

The Adonea (correctly located in

Rosa's plan) most likely refers to the great peristyle of the Domus Augustana

(henceforth the ``Adonea Peristyle´´ [my emphasis]".

Cf. the caption of Pollini (2017b, 102): "Fig. 7.

Rosa's excavation on [the]

Palatine (1868). Dotted ellipse indicates general area in which Bianchini found

the two reliefs [i.e., the

Nollekens Relief and the other relief; cf. here Figs. 36; 37] (M.A. Tomei in

Hoffmann and Wulf [i.e., here A.

HOFFMANN and U. WULF-RHEIDT] 2014 [corr: 2004] fig. 25) [my emphasis]".

Note that

in Pietro Rosa's plan (1868) the area in question is (erroneously) labelled as

follows: HORTI ADONEA?

Note also

that Pollini's `dotted ellipse´, which he added to Rosa's plan, covers part of

the area of Rosa's "PERISTILIUM" and of the "HORTI

ADONEA?". Bianchini cannot possibly have found these two reliefs within

this `dotted ellipse´, because he did not `excavate´ this area at all.

For the

area, where Bianchini had actually `excavated´ (only within the

"BASILICA", the "AULA REGIA" and the "LARARIUM"

of the `Domus Flavia´); cf.

Bianchini's own report and his own plans: Bianchini (1738, 48-68, Tab. II; Tab.

VIII = both here Fig. 8). This has been summarized above, in The major results of this book on Domtian,

and will be discussed in detail below.

Cf. the caption of Pollini (2017b, 102): "Fig. 8.

Reconstruction of sacrarium (form of

superstructure of tempietto unknown) in the Adonea Peristyle (M.A. Tomei ...

[i.e., here M.A. TOMEI 2009] fig.

6)".

With this caption of

his Fig. 8, Pollini gives the impression that the identification of this part

of Domitian's Palace (i.e., the

eastern peristyle) as the "Adonea Peristyle" could possibly be Maria

Antonietta Tomei's hypothesis : but when reading Tomei's article (2009) and Pollini's above-quoted account, it

becomes clear that this is Pollini's own (erroneous) identification.

In his note 11, Pollini writes: "These

two figures were sent to Parma in 1724; Bianchini ... [i.e., here F. BIANCHINI 1738] 54 and 58; P. Zanker ... [i.e., here P. ZANKER 2004] 99, fig.

142". - See for those colossal statues of Dionysos and Hercules also R.

MAR (2009, 253, Fig. 2 [Dionysos], p. 259, Fig. 5 [Hercules]); and supra, Chapter The major results of this book on Domitian, with further

references. Those statues were carved from basanite (basanites), not basalt, as Pollini (op.cit.) erroneously asserts.

In his notes 12-14,

Pollini (2017b) does not discuss the contributions to the monumental volume Gli Orti

Farnesiani sul Palatino, edited by Giuseppe Morganti (1990), of which

especially the article by Silvano Cosmo (1990) is of importance in the context

discussed here; cf. supra, at Chapter

II.3.1.d); Section I., and below.

In his note 15,

Pollini writes: "For the location of the Horti Adonii and the Villa Spada, see Bianchini [i.e., here F. BIANCHINI 1738] 36, 44,

68, et passim, pl. VIII [= here Fig. 8] (in the middle of the plan and

at the bottom just to the left of the excavated Aula Regia and its two flanking

halls). These gardens are better represented

in [Pietro] Rosa's 1868 plan,

reproduced in ... [i.e., here A. HOFFMANN and U. WULF-RHEIDT 2004]

16, fig. 25 (= my fig. 7). Cf. also R. Lanciani, Forma Urbis Romae (Rome, repr. 1990) sector [i.e., fol.] 29. Bianchini

(ibid. 48) mentions the gardens of the

Villa Spada located in this area. In Bianchini's words the reliefs were found

"dentro gli Orti Farnesi, accanto la facciata del giardino Spada". In

the late 19th c.[entury], Ch. Hülsen

(... [i.e., here C. HÜLSEN 1895]

252-83) tried to identify the possible

findspot of the Nollekens Relief, placing it east of Domitian's Cenatio Iovis in the Domus Flavia, in

roughly the same area as I do [my emphasis]".

The "Cenatio Iovis", mentioned by

Pollini (2017b, 102, n. 15), is marked on the plan by Mar (2009, 256, Fig. 3 =

J. POLLINI 2017b, 101, Fig. 6). Cf. the map SAR

1985: "67", where this structure is called: Domus Flavia: "Triclinium" instead. Cf. here Figs. 58; 73, labels: "DOMUS

FLAVIA"; "TRICLINIUM". On Claridge's plan of Domitian's Palace

(1998, 132-133, Fig. 54; ead. 2010,

146-147, Fig. 55) this structure is labelled: "Banquet hall" (cf.

also A. CLARIDGE 1998, 137, Fig. 57; ead.

2010, 150, Fig. 57, the caption reads: "Domitian's Palace. Reconstruction

of the great Banquet Hall and its fountain courts").

As correctly indicated by Pollini (2017b, 102, n. 15),

his passage: "dentro gli Orti Farnesi, accanto alla facciata del giardino

Spada", is actually a verbatim

quote from Bianchini (1738, 48). But note that Bianchini does by no means say

on his page 48, nor anywhere else, anything which could justify Pollini's

conclusion that "In Bianchini's words the reliefs were found" -

"accanto alla facciata del giardino Spada".

We can therefore conclude that Pollini's (2017b,

102, n. 15) interpretation of Bianchini (1738,

48) is wrong, and that fact in its turn

has resulted in Pollini's (erroneous) indication of the findspots of the

Nollekens Relief (and of the other relief, found together with it; cf. here

Figs. 36; 37) on Pollini's Fig. 7: `in or near the Horti Adonea´, and precisely within the area indicated by his

`dotted ellipse´.

In reality, Bianchini (1738, 64, Tab.

V.) is quite outspoken in his

description of the findspot of the Nollekens Relief (cf. here Fig. 36): this and the `other relief´ (cf. here Fig. 37) were found within

the `Aula Regia´.

First, Bianchini (1738,

64) describes the architecture of the `Aula

Regia´, ending on pp. 64-66 with the following phrase:

"Rimangono ancora

in molti siti di questa sala [i.e.

the `Aula Regia´] le incrostature di

marmi nobili segati in grosse tavole, che la vestivano : e la ossatura, per

così dirla , delle pareti è formata tutta di mat- [page 66] mattoni ...".

In the following (on

pp. 66-68), Bianchini allows himself a digression on the numerous brick stamps

found there, which were produced in figlinae,

owned by family members of Domitian called `Flavia Domitilla´. Bianchini

observes that there were altogether four ladies carrying that name, and is

especially interested in those, who were active in the figlinae business. As a result of this inquiry, Bianchini

attributes the construction of the `Aula

Regia´ to Domitian, because many of these brick stamps were found there.

Then Bianchini returns

to his discussion of the finds, excavated within the `Aula Regia´. Cf. Bianchini (1738, 68):

"Qualunque delle

suddette Flavie Domitille fosse la padrona di Felice, che lavorò que'mattoni ;

appartiene sempre alla età del suddetto Principe [i.e., Domitian] : e

dimostra, che questi saloni ( giacchè ne' prossimi ancora al maggiore si

ritruovano in opera dentro le arcate delle volte simili suggelli di quel Felice

) siano fabbricati da Domiziano. Si è

ricavato altresì il medesimo tempo della struttura [i.e., of the `Aula Regia´] da un basso rilievo qui ritrovato, ove

Tito [i.e., in reality Domitian] fratello di Domiziano rappresentasi in atto

di sacrificare [i.e., the

Nollekens Relief; cf. here Fig. 36], di cui qui [cf. on the border: "Tav. VI."] riporto la figura ; con

l'altro frammento di una tavola simile [i.e.,

the other relief = here Fig. 37], in cui vedesi un [cf. on the border:

"Tav. VII."] sacrificio fatto da femmine : la quale può

credersi che rappresentasse il sacrificio alla Buona Dea solito farsi dalla

moglie del Pontefice Massimo quali furono dell'Imperatore Domiziano Giulia di

Tito, e Domizia [my emphasis]".

Pollini (2017b,

100-101) does not discuss Bianchini's above-summarized passage (1738, 64-68) in

its entirety. He, therefore, overlooks the true meaning of what Bianchini

writes on p. 68 ("questi saloni ...

al maggiore ... Si è ricavato altresì il medesimo tempo della struttura"),

namely that both reliefs had occurred within that grand structure he describes

in detail on pp. 64-68: the `Aula Regia´.

But Pollini (2017b,

100-101) provides an English translation of that part of the quote from

Bianchini (1738, 68), which I have written above in bold, and adds useful

comments:

"The dating of the

building [i.e., of the `Aula Regia´] is also established by the

fact that found here was a bas-relief [i.e.,

the ``Nollekens Relief´´] in which Titus, brother of Domitian, is represented

in the act of sacrificing, a figure which I show here (pl. VI = fig. 2 here

[cf. here Fig. 36]); with [regard

to] the other fragment of a similar panel, in which a sacrifice by females is

to be seen (pl. VII = fig. 5 here [= here Fig.

37]), the latter [relief] can be understood as representing the sacrifice

to the Bona Dea, usually performed by the wife of the Pontifex Maximus, [but]

who were [in the case] of the emperor Domitian, Iulia Titi [daughter of Titus]

and Domitia [wife of Domitian] [with n. 8; page 101].

Contrary to Bianchini's comment, the headless female figures

in the second relief have nothing to do with a sacrifice since no altar or

sacrificial accouterments [!] are depicted, nor is there anything to indicate

that the niece or wife of Domitian appears; rather, the presence of a

bare-breasted female would suggest that the figures are personifications or

divinities [with n. 9]. The bare-breasted figure in the center appears to carry

in her right hand a small pouch (if indeed the engraver has represented this

object correctly [with n. 10])".

In his note 8,

Pollini writes: "Since Iulia Titi was never the wife of Domitian, the

sense of the last phrase is better conveyed by the Latin [i.e., by the Latin version of F. Bianchini's 1738 text, printed

opposite the Italian text] (``quo loco habuit Domitianus Juliam Titi ac

Domitiam´´)".

In his note 9, he

writes: "The upper torso of one of the other three figures is

substantially preserved and shows that the breasts were draped".

In his note 10,

he writes: "Engravers often misrepresented objects they did not

understand, as in the case of the sacrificial ``pitcher´´ carried by the boy

ministrant in the Nollekens Relief (see below)".

To Pollini's own interpretation of the `other relief´

(cf. here Fig. 37), I will come back below (cf. infra, at ChapterV.1.i.3.b); Section III.).

Pollini also suggests,

where precisely in Domitian's Palace the Nollekens Relief (cf. here Fig. 36) could have been on display.

Since he has not realized that Bianchini (1738, 68) actually says that both

reliefs were found within the `Aula Regia´,

the suggestions he makes for the display of the Nollekens Relief could only be

true, provided at least that that relief had occurred in a secondary context.

Let's first of all read

what Pollini writes about the presumed state of the Nollekens Relief, when that

was found in 1722.

Pollini (2017b,

112-113, Section: "Analysis of the condition of the Nollekens Relief") writes:

"Also skillfully

masked in the 18th c.[entury] were the repairs [page 113] to the relief of not

only restored elements but also original parts, including the ancient heads of nos. 6 [Domitian], 8 [Genius Senatus], and 10 [boy ministrant], which were presumably found separated at

the time of excavation, when the relief itself may have been found in as many

as 6 pieces (along all of the principal cracks). (If the relief were not broken when first discovered, then we would have

to presume that it suffered some serious mishap thereafter) [my

emphasis]".

Let's now turn to

Pollini's suggestions about where the Nollekens Relief could have been on

display within Domitian's Palace.

Cf. Pollini (2017b,

103, Section: "Bianchini and the place of discovery"):

"The imperial

sacrifice on the Nollekens Relief would have been appropriate for display in a

state room of the Domus Flavia. One possibility is the adjacent room on the E[east] side of the Aula Regia

(Salon du [!] trono) (fig. 6). This room (which Bianchini called the

``Lararium´´ [cf. here Figs. 8; 8.1,

label: "LARARIUM"; Figs. 58;

73, labels: "DOMUS FLAVIA"; "LARARIUM"]) apparently had

an altar (later demolished) revetted with marble and set against the middle of

its back S[outh] wall [with n. 19] ... The depth of each of the 5 niches is

suitable at 1.18 m [with n. 21]. Another possible location for the Nollekens

Relief is in the area of the great colonnaded vestibule to the southeast [with

n. 22], next to the ``Lararium´´, or in one of the suites of rooms between the

two parallel peristyles of the Domus Flavia and the Domus Augustana (fig. 6)

[with n. 23]".

In his notes 19,

21-23, Pollini provides references and further discussion.

The correct findspot of the Nollekens Relief, as

indicated by Bianchini (1738, 68) in the above-quoted passage, was already known to Silvano Cosmo. I

therefore repeat in the following a passage, written above (cf. supra, at Chapter II.3.1.d); Section I.):

`When we compare

Silvano Cosmo's plan (1990, 837, Fig. 8 [= here Fig. 39]) with the relevant detail of G.B. Nolli's map (cf. C.

KRAUSE 1990, 122, Fig. 1), also illustrated by T.P. Wiseman (2019, 43, Fig.

16), it turns out that Bianchini had `excavated´ in the so-called Aula Regia and in the immediately

adjacent halls `Basilica´ and `Lararium´, both within the `Domus Flavia´; cf. here Figs. 58; 73, labels: "DOMUS

FLAVIA"; BASILICA"; "AULA REGIA"; "LARARIUM". -

For the modern name `Aula Regia´; cf.

Claridge (1998, 132-133, Fig. 54, p. 135; ead.

2010, 146-147, Fig. 55, p. 148): "`Aula Regia´ or Audience Chamber".

See also the map SAR 1985, labels:

64: Domus Flavia: "Basilica"; 65: Domus Flavia: "Aula

Regia"; 66: Domus Flavia:

"Lararium"´.

As we have seen above, Pollini

(2017b, 101) suggests instead that the

Nollekens Relief (and the other relief, found by Bianchini together with it)

were found in or near the Adonea, an

ancient toponym, which Pollini (erroneously) locates within the Domus Augustana.

There are several problems connected with Pollini's just

quoted hypothesis, that will be discussed in the following.

Francesco Bianchini's

own measured plan of Domitian's Palace, where he had found the Nollekens Relief

(cf. id. 1738, his Tab. VIII. [= here

Fig. 8]), is drawn to "Scala

Pedum Romanorum Mille", and is dated 1728. Note that in the plans of

Bianchini (1728, published 1738) and of Pietro Rosa (1868 = Pollini's Fig. 7)

north is approximatly in the middle of the bottom of their plans. - For the

problem involved; cf. supra, at

Chapter The major results of this book on

Domitian and here Fig. 8.1, with

its relating caption.

By writing: "...

Both [reliefs] were probably found in or

near the Horti Adonii or Adonea, in an area that separates the

``private sector´´ (Domus Augustana) from the ``state sector´´ (Domus Flavia)

of the palace, and just northeast of the grand triclinium of the latter [my emphasis]" - Pollini (2017b,

101) refers to Pietro Rosa's plan of 1868, in which Rosa has tentatively

located the: "HORTI ADONEA?" precisely there, where Pollini locates

the Horti Adonea in this passage.

Bianchini (1738, 68; cf. his plan Tab. VIII.

[= here Fig. 8]) does not write that the Nollekens Relief

was found "in or near the Horti

Adonii or Adonea", as

Pollini (2017b, 101) asserts. On the contrary, Bianchini makes clear by the

lettering on his plan Tab. VIII. that the area, identified by him as the Adonea, belonged to the Orti of the

Conti Spada. Note that Bianchini (1738) and Rosa (1868) locate the Adonea at the same site within

Domitian's Palace.

In addition to this,

Bianchini (1738, 68; cf. his plan Tab. VIII. [= here Fig. 8]) writes explicitly that the Nollekens Relief and the other

relief were found in that hall of the Palace, where also "the colossal

basalt statues of Hercules and Bacchus/Dionysus with Pan (now in Parma's

Galleria Nazionale)" were excavated, as Pollini writes (cf. id. 2017b, 101, n. 11, quoting for that,

F. BIANCHINI 1738, 54 and 58). - And that hall is located within the `Domus Flavia´, and was by Bianchini

himself (cf. his plan Tab. II. = here Fig.

8) and is still today referred to as `Aula

Regia´.

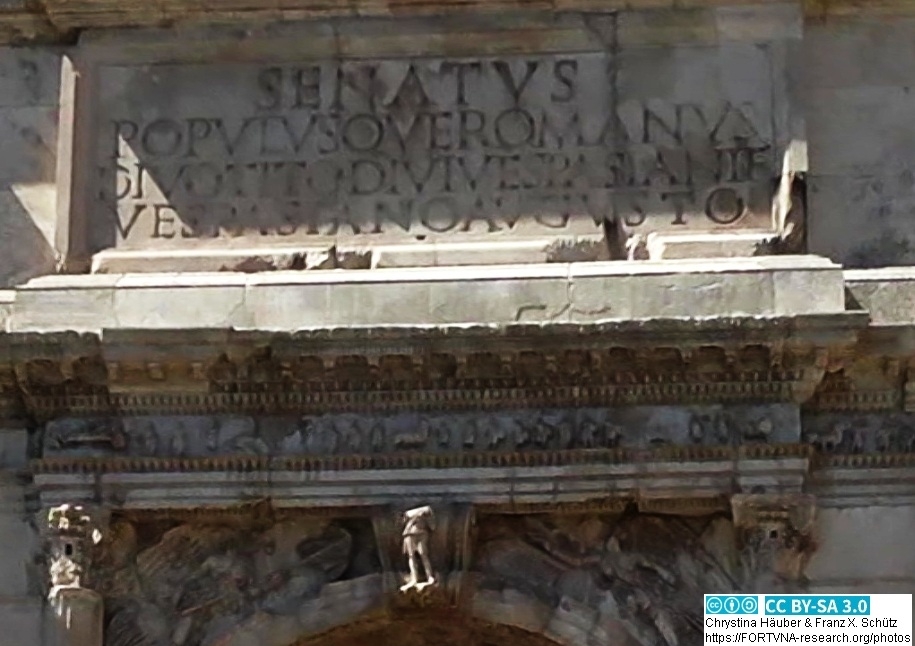

The captions of the illustrations of both reliefs; cf.

Bianchini (1738, Tab. VI.: the Nollekens Relief (cf. here Fig. 36): and Tab.

VII.: `the other relief´; cf. here Fig. 37) add to this expressis verbis that the area in question, where Bianchini found

those two reliefs, belonged to the Orti Farnesiani.

See the caption of the

etching of the Nollekens Relief; cf. Bianchini (1738, Tab. VI.; cf. here Fig. 36):

"1. Imp. Titus

coronatus et velatus sacrificat super aram ... [follows the description of the

other figures that appear on this relief] Anaglyphum marmoreum repertum anno

MDCCXXII in Palatio Caesarum intra Hortos Farnesianos

Hieronymus Rossi

incid.".

See also the caption of

`the other relief´; cf. Bianchini (1738, Tab. VII. = Fig. 37):

"Fragmentum

anaglyphi repertum in Palatio Caesarum intra Hortos Farnesianos MDCCXXII

Hieronymus Rossi

incid.".

Whereas Bianchini (1738) indicates with the lettering on

his plan Tab. VIII. (cf. here Fig. 8) that the area, (erroneously) identified

by him - by Pietro Rosa (1868) and by Pollini (2017b) - as the Adonea,

belonged to the Orti of the Conti Spada:

"Pars Mediana Palatii Caesarum Continet Theatrum

Tauri et Hortos Adonios ubi hodie Horti Co : Spada".

Note that underneath this lettering (i.e., in reality to the north of it),

Bianchini has drawn the ground-plan of the relevant garden. And underneath the

drawing of this garden (i.e., in

reality to the north of it) appears his lettering: "ADONEA sive Horti

Domitiani Augusti [my emphasis]".

When looking for the

first time at Bianchini's (1738, Tab. VIII. = Fig. 8) `Adonis garden´ in Domitian's Palace, I had the impression

of knowing this garden already, and therefore read his detailed explanations,

given in the letterings on his plan Tab. VIII. : only to find out that

Bianchini did not draw the flower beds and a central pool of his Adonea after some real ancient

architectural finds seen by him at this site. His layout of the Adonea is instead inspired by the

garden, represented on the Severan Marble Plan, which already Giovan Pietro

Bellori had correctly identified as `Domitian's garden of Adonis´. The garden,

which appears on these fragments of the Severan Marble Plan, has now been

identified with the excavated garden on the large terrace (measuring circa 135

× 165 m = 19.000 square metres) of that part of Domitian's Palace, which is

located at the north-east corner of the Palatine, in the area of the (former)

Vigna Barberini. - To all this I will come back below.

Bianchini (1738) comments

on his representation of the Adonea

in the lettering of his plan Tab. VIII. (= here Fig. 8 as follows:

"Indicationes

adhibitae ad Ichnographiam partis Orientalis Palatii Caesarum quae et DOMVS

AVGVSTANA

... Κ Ψ Φ Horti Adonii

expressi in Vestigio Veteris Romae [`Vestigio Veteris Romae´ is the title of

Giovan Pietro Bellori's book of 1673, which will be discussed below], ubi à

Domitiano exceptum Apollonium Thyanaeum [?] scribit Philostratus, observante in

Notis Belloris: à quo eoru structura juxta morem Assyrium erudite

explicatur".

Bianchini (1738, 68; cf. his

plan Tab. VIII. = here Fig. 8) mentions the find of the Nollekens Relief (F.

BIANCHINI 1738, Tab. VI.) and that of

`the other relief´ (F. BIANCHINI 1738, Tab. VII.) within the `Aula Regia´, that

is to say that "sala", which is correctly indicated on Cosmo's plan

(1990, 837, Fig. 8 = here Fig. 39) as the area, where Bianchini had

`excavated´.

Cf. the map SAR 1985, label: 65: Domus Flavia:

"Aula Regia" (for the relevant detail of this map: LTUR IV [1999] fig. 6, s.v. Palatium); cf. Claridge (1998,

132-133, Fig. 54, p. 135; ead. 2010,

146-147, Fig. 55, p. 148): "`Aula Regia´ or Audience Chamber".

That part of Domitian's

Palace on the Palatine, which Francesco Bianchini (1738, plan Tab. VIII. [=

here Fig. 8]) and Pietro Rosa (1868

[= J. POLLINI 2017b, Fig. 7]) identified with Domitian's Adonea, whom Pollini (2017b) now follows, is not any more regarded

as such. The Adonaea were instead a

garden on the (in part) artificial terrace, built by Domitian within his Palace

at the north-east corner of the Palatine, known from fragments of the Severan

Marble Plan which carry the inscription DI(aeta)

(a)DONAEA. Later this terrace was occupied by the Vigna Barberini.

With the identification of the ancient garden at the

Vigna Barberini with Domitian's Diaeta

Adonea, I follow Filippo Coarelli (2009b, 90-91, Figs.

32; 33: "Frammento della pianta marmorea severiana con Adonaea. Lo stesso con la ricostruzione

teorica del portico e l'aggiunta del frammento con la scritta DIA"; cf. F. Coarelli, in: F.

COARELLI 2009a, pp. 438-439. cat. no. 29).

Of the same opinion is Maria Antonietta Tomei (2009, 288). - See now also Eric M. Moormann (2018,

172, n. 67), and Ulrike Wulf-Rheidt

(2020, 186).

I have elsewhere summarized the recent findings

concerning Domitian's `Adonis Garden´ within his Palace on the Palatine;

cf. Häuber (2014a, 301-302; see also

p. 684):

"The excavations in the Vigna Barberini on

the Palatine (map 3 [= here Fig. 71], labels: PALATIUM; Vigna

Barberini) have shown that the

rectangular terrace which enlarged the plateau of the hill was finished under

Domitian as part of his palace [with n. 107]. So far only one third of the

building has been uncovered; the substructures of its north wing may have

accommodated the Tabularium principis

[with n. 108]. In the large garden of

this building occurred several rows of half amphorae

embedded in the soil, but upside down. According to Françoise Villedieu [with

n. 109], this unusual practice checked

the growth of those plants. The excavators do not follow Giovan Pietro Bellori

[with n. 110], who was first to identify

this building with the aule Adonidos

[with n. 111], a building in the

Palatine palace where Domitian sacrificed to Minerva and received Apollonius of

Tyana (Philostratus, VA 7, 32)

[with n. 112]. Philostratus says that

this place `was bright with baskets of flowers, such as the Syrians at the time

of the festival of Adonis make up in his honour´ [with n. 113]. This old hypothesis was based on the fact

that the fragments nos. 46a-d of the Severan marble plan [with n. 114] show a large garden, the lettering of which

Coarelli [115] reconstructs as Di(aeta) [page 302] (a)DONAEA.

These fragments do not show adjacent structures, which is why the location of

the represented building is controversial [with n. 116]. Coarelli [with n. 117] believes

that these half-amphorae prove his

identification of this building as the Diaeta

Adonaea. I follow him, since, in my opinion, there is no alternative on the

Palatine (maps 3 [= here Fig. 71]; 6, labels: DI(aeta) (a)DONAEA; S. Sebastiano; ``AEDES ORCI´´ [with

n. 118]; SOL INVICTUS ELAGABALUS; IUPPITER ULTOR; Vigna Barberini); also Maria Antonietta Tomei, who has

studied the gardens within the various domus

and imperial palaces on the Palatine for many years, shares this opinion

[with n. 119]. Linda Farrar, taking it

for granted that this building is, in fact, the Adonaea, comments on these finds from the perspective of garden

studies; her observations perhaps corroborate Coarelli’s hypothesis: ``The

pots had been set in the ground into a bed of marble chippings and because they

were placed so close together, the pots may have served as receptacles for

plants associated with the cult of Adonis. A wider spacing would indicate

permanently planted pots of flowers or shrubs instead …´´. And on the Diaeta Adonaea of

the Severan marble plan Farrar remarks: ``… An elongated rectangular

feature across the centre of the garden

could be a euripus, and the series of

irregularly shaped boxes that surround it may be flower beds. However, four

blocks, each of four lines (with serifs) have remained a puzzle; these perhaps

detail benches or beds upon which the pots containing `Adonis Gardens´ could

have been placed. After the plants had died, they could then have been thrown

into water, in this case the euripus,

to complete the full ritual´´ [with n. 120; my emphasis]".

In my note 107, I

quote: "M.A. Tomei and F. Villedieu

have recently excavated at its north-east corner a structure which they

identify as the coenatio rotunda in

the Domus Aurea (Suet., Nero 31); cf. Carandini et alii 2011, p. 143. They [i.e., A. CARANDINI et al. 2011, 143] themselves interpret this structure as a

``torre-tempietto´´ instead and identify the coenatio rotunda with the octagonal room within the `Esquiline

Wing´ of the Domus Aurea [cf. here Fig. 71, labels: MONS OPPIUS; DOMUS

AUREA]; cf. p. 145, fig. 11; Carandini, Carafa 2012, Tav. 110-112".

Cf. note 108:

"Coarelli 2009b, p. 78 with ns. 104, 105; cf. Villedieu 2009, pp. 246-247; according

to her the size of the terrace measured c. 135 × 165 m / 19.000 square meters

[my emphasis]". - For the Tabularium Principis, which was

certainly accommodated within this substructure; cf. now infra, at Appendix IV.b.2.).

Cf. note 109:

"Cf. Villedieu 2001, p. 98; Coarelli 2009b, p. 91 with n. 277".

Cf. note 110:

"Bellori 1673, pp. 47-48, ``TABVLA XI Donea. Adonea, sive Adonidis Aula´´,

who bases his correct identification on ancient literary sources (I had the

chance to consult this book at the British School at Rome, BSR); cf. the

commentary on this work by Muzzioli 2000; Beaven 2010, p. 330 with n. 25".

Cf. note 111:

"So Sulze 1940, p. 513 (without providing a reference)".

Cf. note 112:

"Richardson Jr. 1992, pp. 1-2 figs. 1; 2".

Cf. note 113:

"Translation: Farrar 1998, p. 185 with n. 51; cf. Frass 2006, p.

282".

Cf. note 114:

"Cf. M. Royo, s.v. Adonaea; s.v. Adonis, Aula; Άδώνιδος αύλή, in LTUR, I, 1993, pp. 14-16; 16, figs. 1;

2".

Cf. note 115:

"Coarelli 2009b, pp. 90-91; F. Coarelli, in Coarelli 2009a, pp. 438-439,

cat. no. 29".

Cf. note 116:

"M. Royo, s.v. Adonaea; Adonis,

Aula; Άδώνιδος αύλή, in LTUR, I,

1993, pp. 14-16; 16, figs. 1; 2".

Cf. note 117:

"Coarelli 2009b, pp. 90-91; F. Coarelli, in Coarelli 2009a, pp. 438-439,

cat. no. 29".

Cf. note 118:

"C. F. Coarelli, s.v. Orcus,

Aedes, in LTUR, III, 1996, p. 364.

Cf. note 119:

"Tomei 2009, p. 288, cf. passim

(referring to earlier studies)".

Cf. note 120:

"Farrar 1998, p. 185 with ns. 51-55 (with references); cf. p. 7 (with

fig.); cf. for the relevant rituals also Marzano 2008, pp. 3-4 with ns. 6, 7,

fig. 3".

To my above-quoted note 109, I should like to add the

following publications on the cenatio

rotunda in Nero's Domus Aurea,

which has now been identified with the structure, excavated at the (later)

Vigna Barberini.

Cf. Franςoise Villedieu

(2010; ead. 2011a; ead. 2011b; ead. 2012; ead. 2015a; ead. 2015b; ead. 2016, 107, n. 2; ead.

2021 [with complete bibliography]); Filippo Coarelli (2012, 504, 509; id. 2015; id. 2021), and Edoardo Gautier di Confiengo (2021), the findings of

which the author was kind enough to share with me. Gautier di Confiengo (2021)

and Eric M. Moormann (2020b, 19-23), to which Gautier di Confiengo has alerted

me as well, compare Nero's cenatio

rotunda on the Palatine also with the octagonal room within the `Esquiline

Wing´ of the Domus Aurea. Both of

which had approximately the same dimensions : diameter circa 16 m, but the

`Esquiline Wing´ of the Domus Aurea

on the Mons Oppius was, as Moormann

(2020b, 21) writes: "situato in una parte secondaria ed intima della

residenza", whereas the cenatio

rotunda of the Vigna Barberini, given its location within Nero's Domus Aurea located on the Palatine,

that served the emperor's official functions like receptions, was obviously

"una struttura per i banchetti di stato ufficiale"; cf. Moormann

(2020b, 21 with n. 19, providing references). Edoardo was, in addition to this,

kind enough to send me the `3D´-reconstructions of the Domus Aurea, created by Marco Fano and published by Clementina

Panella (2013, 101, Fig. 122, p. 113, Fig. 136).

The caption of

Panella's Fig. 122 reads: "Ricostruzione 3D del paesaggio della Domus Aurea vista da Est.

(Elab.[orazione] Marco Fano)". The caption of her Fig. 136 reads:

"Ricostruzione 3D dell'atrio vestibolo e dello stagnum guardando verso il Palatino/Velia. (Elab.[orazione] Marco

Fano)".

Into these two reconstructions,

Panella's Figs. 122 and 136, is also integrated Nero's cenatio rotunda on the Palatine. For a plan, into which both Nero's

cenatio rotunda on the Palatine and

the octagonal room within the `Esquiline Wing´ of the Domus Aurea on the Mons Oppius

are likewise integrated; cf. Villedieu (2010, 1090, Fig. 1.: "Vestiges du

palais de Néron ...", who refers to her n. 2 for the cartographic sources

of her plan. Interestingly, Villedieu's location of Nero's cenatio rotunda within the area of the (later) Vigna Barberini

differs from that of the location of this structure, as assumed on Marco Fano's

`3D´-reconstructions of the Domus Aurea,

published in Panella (2013). Fano's location of Nero's cenatio rotunda on the Palatine was also marked on a plan, that had

been added as a loose sheet to the exhibtion-catalogue on Nero, edited by Maria

Antonietta Tomei and Rossella Rea (Nerone,

2011), and has the following title: "Nerone Nero 12.04.-18.09.2011 Il

Percorso della Mostra The Exhibition Itinerary", label 7: "coenatio

rotunda".

In our maps, I have

followed the location of the cenatio

rotunda, as suggested by Villedieu (2010, Fig. 1).

Cf. here Figs. 58; 71; 73, labels: PALATIUM;

DI(aeta) (a)DONAEA; S. Sebastiano; "AEDES ORCI"; SOL INVICTUS

ELAGABALUS; IUPPITER ULTOR; site of Nero's CENATIO ROTUNDA; Vigna Barberini:

MONS OPPIUS; DOMUS AUREA.

ChapterV.1.i.3.b); Section III. Does the design of the Nollekens Relief reflect

the topographical

context, for which Domitian had commissioned it?

Pollini (2017b, 113,

Section: "An emperor sacrificing") describes Domitian's figure on the

Nollekens Relief in detail:

"As the primary

and tallest figure, the emperor

[Domitian; no. 6] is shown in the

middle, sacrificing over a small altar laden with offerings and decorated with

ox-heads and garlands. He wears the noble and voluminous toga; this is probably

the toga picta, the embroidered

purplish toga of the triumphator, and

would originally have been painted. The emperor's head [at least on the photo

here Fig. 36] is well preserved and

shows no evidence of recutting. Under his veil he wears a laurel crown, the

tips of which appear to be broken off. The other figures probably also wore

laurel crowns at the sacrifice, with the exception of the helmeted female

personification (no. 11 [i.e., the Dea Roma]) [with n. 63]. On the emperor's feet are calcei patricii, the high double-knotted

red shoes of the patriciate [with n. 64]. The location of the altar and the

turn of his [i.e., Domitian's] body

suggest that the emperor was pouring a libation from a patera, evidently correctly re-created by the restorer. In his other hand, the emperor holds a

large book scroll of a type not generally known in antiquity; ancient book

scrolls held by Roman magistrates, by contrast, were typically very small [with

n. 65; my emphasis]".

In his notes 63-65,

Pollini provides references and further discussion.

In his note 65,

Pollini writes: "See, e.g., the scroll held by Gaius Caesar on the

so-called Sandaliarius Altar from Rome, now in the Uffizi Gallery and the

``Tiberius Relief´´ on loan to the Getty Villa Museum. For the former, see ...

[i.e., here J. POLLINI 1987] 33-34,

pl. 14.1; for the latter ... [i.e.,

here J. POLLINI 2012] 97, fig. II.31a".

As on Frieze A of the

Cancelleria Reliefs (cf. here Fig. 1;

Figs. 1 and 2 drawing: figure 6), Domitian holds, in my opinion, also on

the Nollekens Relief (cf. Fig. 36: figure 6) a rotulus in his left hand.

Pollini (2017b, 113)

does not explain the just-mentioned iconographic feature `book scroll´, nor

does he draw comparisons with the Cancelleria Reliefs in this case. Concerning

the rotulus, held by Domitian (now

Nerva; cf. here Figs. 1; 1 and 2

drawing: figure 6) himself on Frieze A of the Cancelleria Relief, and

concerning the rotulus, carried for Vespasian

by one of the men of his entourage on Frieze B of the Cancelleria Reliefs (cf.

here Figs. 2; 1 and 2 drawing: figure 17),

I myself have followed the interpretation, given by Erika Simon (1963, 9, 10,

quoted verbatim supra, in Chapters I.2.1.a), and V.1.b), and infra, at Chapter VI.3.), and repeat it here again:

`to both emperors on

the two friezes of the Cancelleria Reliefs [cf. here Figs. 1; 2; Figs 1 and 2 drawing] belongs a rotulus. Domitian (now Nerva) on Frieze A carries it himself in his

left hand, whereas for Vespasian a rotulus

is carried by a man of his entourage. Both rotuli

contain the vota of these emperors,

made by them to the gods, praying them to be granted a victory in the war, to

which Domitian on Frieze A is shown as leaving, whereas in Vespasian's case on

Frieze B this victory has already been granted - according to Simon (1963, 9,

10) these were the vota taken by the

commander of an army pro reditu´. -

To this I will come back below.

Pollini (2017b)

describes also the other 10 figures that appear on the Nollekens Relief in

detail. I will only mention them shortly. For the following, see the numbering

of these figures on here Fig. 36. As

we have already heard above, the Emperor Domitian is figure no. 6 on this

relief.

Cf. Pollini (2017b,

113, Section: "Cult personnel"): the figure no. 5 in the

background is a tibicen, nos. 2 and 10 are "young sacrificial attendants, ministri". They are precisely "paedagogiani (servile

pages)", and belong to Domitian's household. Cf. pp. 114-115 (Section:

"Lictors and a soldier"): two lictors (nos. 1 and 4) with

"fasces laureati which imperial fasces bore usually on the occasion of a triumph [with n. 76; page

115] ... Both lictors wear low, common-style shoes (calcei) appropriate for freedmen, the class to which most lictors

belonged [with n. 78]. Both are paludati,

wearing not a civic toga but a tunic and a military cloak, fastened with a

round fibula. The same type of tunic and military cloak fastened with a fibula is worn over the shoulders of the

background figure (no. 3), but he bears no fasces over

his left shoulder and because of his beard [with n. 79] is probably a Roman soldier of a stock type

[my emphasis]".

In his notes 76,

78-79, Pollini provides references.

Pollini (2017b, 115, n.

79) writes: "Traces of the beard of this figure [no. 3, i.e., of the soldier] are barely visible

in the present relief (fig. 12 [i.e.,

the Nollekens Relief, here Fig. 36,

illustrating with this photograph its current, badly damaged state]). For the

bearded soldiers in the 1st. c.[entury] A.D., see A. Bonanno, Portraits and other heads on Roman

historical relief up to the age of Septimius Severus (BAR S6; Oxford 1976)".

Hans Rupprecht Goette (Schwertbandbüsten der Kaiserzeit. Zu