by Chrystina Häuber

see link to "Preview Ehrenstatue für Hadrian in Rom".

Der

folgende Text enthält Literaturangaben und viele Abbildungsnummern.

Vergleiche FORTVNA PAPERS vol. III-1, S. 1097 ff.

für die entsprechenden Bildunterschriften ("List of illustrations"),

S. 1128, für die Abkürzungen ("Abbreviations")

, und

S. 1129 ff., für die Literatur ("Bibliography")

.

Dieser Band ist open access auf unserem Webserver publiziert. Siehe:

https://FORTVNA-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3.html

go directly to the update at the end of the following text from 21.2.2025

Let's first of all look at the illustrations of this text.

Fig. 21. Anaglypha Hadriani, adlocutio or alimenta relief, marble. Rome, Forum Romanum, Curia Iulia. Photo: D-DAI-ROM- 68.2783. Because this relief was painted, I believe that in its original state the artists had not only differentiated the represented people by appropriately colouring their garments and shoes, but that they had also characterized the represented statues as such: the seated Trajan, the representation of Italia with her two children, and the statues of the fig tree and of Marsyas.

Fig. 22. Anaglypha Hadriani, `burning of debt records´ relief, marble. Rome, Forum Romanum, Curia Iulia. Photo: J. Felbermeyer D-DAI-ROM- 68.2785. Because this relief was painted, I believe that in its original state the artists had not only differentiated the represented people by appropriately colouring their garments and shoes, but that they had also characterized the represented statues of the fig tree and of Marsyas as such. Scholars agree that both Anaglypha Hadriani were on display on the Forum Romanum, but it is debated, where exactly they had been erected.

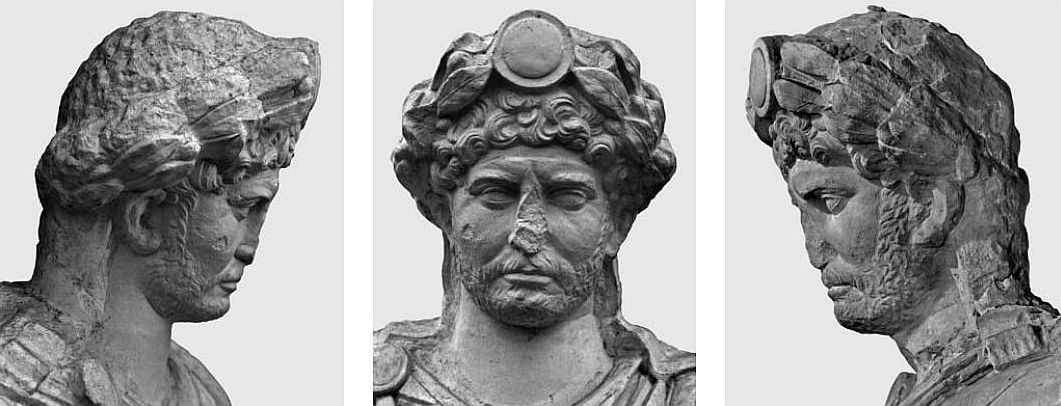

Fig. 29. Over lifesize cuirassed statue of the Emperor Hadrian, marble, 2,68 m high (comprising the plinth), 2,54 m high (without the plinth), his cuirass is decorated with an Athena/ Palladion, crowned by two winged Victories, standing on the lupa Romana, suckling the infants Romulus and Remus. Hadrian sets his left foot on a small human figure (representing the Roman Province of Judaea?). Found at Hierapydna in Crete. Istanbul, Archaeological Museum (inv. no. 50); suggested date: 132-138 AD.

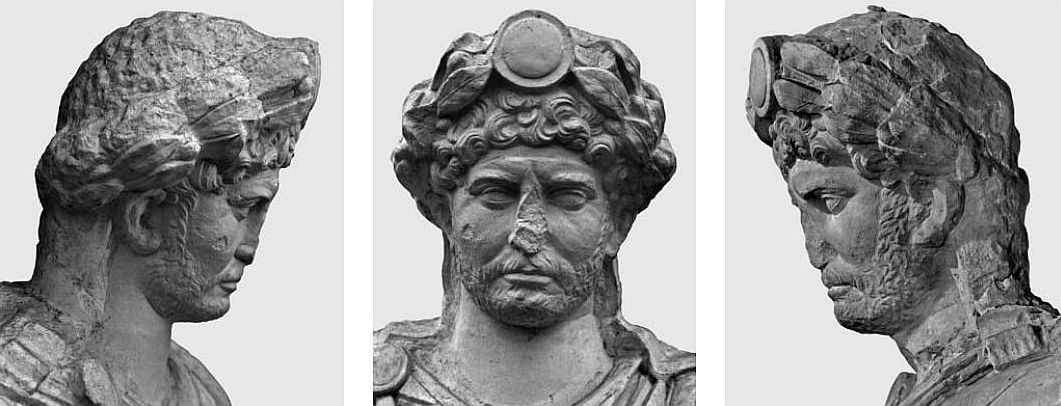

In my opinion, the prototype of this portrait of Hadrian belonged with the inscription (CIL VI 974 = 40524 = here Fig. 29.1) to the victory monument, dedicated in Rome in honour of Hadrian by the Senate and the Roman People in AD 134/5 (so G. ALFÖLDY 1996 = here Fig. 29.1), in AD 135 (so C. BARRON 2018), or in AD 135/6 (so W. ECK 2003, 162, n. 35) to commemorate his victory in the Bar Kokhba Revolt.

Provided, the prototype of this portrait-statue of Hadrian is represented on Hadrian's coins (here Fig. 129, above; Fig. 129, below, left; Fig. 129, below, right), as is suggested here, the fact that Hadrian is represented laureate on the obverses of those coins, allows the following assumption: that those coins commemorate Hadrian's second imperatorial acclamation, which the emperor accepted in AD 136 for the suppression of the Bar Kokhba Revolt.

Photos of the statue and of its cuirass: Courtesy of H.R. Goette (April 2023). Photos of the statue's head: from P. Karanastasi (2012/2013, 387, Tafel 6, 3-5).

Fig. 29.1. Fragmentary inscription (CIL VI 974 = 40524), marble, once belonging to an honorary statue of the Emperor Hadrian, dedicated to him by the Senate and the Roman People to commemorate his victory in the Bar Kokba Revolt (so W. ECK 2003, 162-165; M. FUCHS 2014; C. BARRON 2018); and according to G. Alföldy (at: CIL VI [1996] 40524, who restored the inscription as shown here, dating it to AD 134/5); and M. Fuchs (2014, 130) erected within the cella of the Temple of Divus Vespasianus in the Forum Romanum. From: M. Fuchs (2014, 131, Fig. 8: "CIL, VI, Pars VIII, Fasc. II [1996], 40524 [on 25th November 2024 E. Thomas has kindly alerted me to the fact that the text should read: "Syriam Palaestinam" instead of "Palaesinam"] ". According to C. Barron (2018, who follows in this respect W. ECK 1999-2003), the honorary statue, to which this inscription belonged, stood "beneath (in front of?)" the Temple of Divus Vespasianus, its inscription is kept in the Capitoline Museums, Rome (inv. no. NCE 2529), and is datable: "135 CE Sep 15th to 135 CE Dec 9th". C. Evers (1991, 797, n. 72), according to whom this inscription was found in the Forum Romanum, asks instead, whether it belonged to the colossal statue of Hadrian (now Constantine the Great), here Fig. 11. For a discussion; cf. <https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Konstantin_Hadrian_Koloss_01.html>.

In my opinion, this dedication belonged to the honorary statue, after which Hadrian's portrait-statue from Hierapydna at Istanbul (here Fig. 29) and almost 30 replicas of this portrait were copied. See above, in volume 3-1, pp. 899-959, at A Study on Hadrian's portrait-statue from Hierapydna (cf. here Fig. 29); and in this volume, at Appendix IV.c.2.

Fig. 129, above. Sestertius (`not earlier than AD 134´; so P.L. STRACK 1933). The reverse shown here appears on several coin-types that were issued at Rome by Hadrian. They show the cuirassed emperor in `archaic oriental victor pose´, with spear and parazonium, stepping with his left foot on a crocodile. Photo taken after a plaster cast of a sestertius of the Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Napoli. From: A.C. Levi (1948, 30-31 with n. 1, Fig. 1).

The British Museum, London owns four coins, minted by Hadrian in Rome with reverses that show the emperor in the same iconography as on the sestertius (here Fig. 129, above). In the catalogues of the British Museums those four coins are all dated as follows: AD 130-138.

Apart from the here following two coins (here Fig. 129, below, left and Fig. 129, below, right), these are the following coins: sestertius, Museum number R.9089 (RIC 2, Hadrian 782, p. 440) [see for a better preserved copy of this sestertius: L. CIGAINA 2020, 267 with n. 801, Fig. 113]; and sestertius, Museum number R.9090 (RIC 2.3, Hadrian 1455).

The fact that Hadrian is represented laureate on the obverses of those coins, allows, in my opinion, the following assumption: that those coins commemorate Hadrian's second imperatorial acclamation, which the emperor accepted in AD 136 for the suppression of the Bar Kokhba Revolt.

Fig. 129, below, left. Dupondius or As, issued by Hadrian in Rome in AD 130-138. The British Museum, London. Museum number 1867,0101.2166. "Obverse: Laureate head of Hadrian, facing right. Inscription: HADRIANVS AVG COS III P P. Reverse: Hadrian, in military dress, standing [in `archaic oriental victor pose´] facing right, holding a vertical spear in his right hand and a parazonium upright in his left, his left foot is on a crocodile, who is lying facing right, his head turned back to the left. Inscription: S C. RE3 / Coins of the Roman Empire in the British Museum, vol. III: Nerva to Hadrian (1617, p. 485) Strack ([1933] Hadrian) / Die Reichspraegung zur Zeit des Hadrian (701) RIC2 / The Roman imperial coinage, vol. 2: Vespasian to Hadrian (830, p. 444) RIC2.3 / The Roman Imperial Coinage, vol. II - part 3 from AD 117-138 Hadrian (1457)". Courtesy of the British Museum, London. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

Fig. 129, below, right. Denarius, issued by Hadrian in Rome in 130-138 AD. The British Museum. Museum number 1972.0711.4. "Obverse: Laureate head of Hadrian, right. Inscription: HADRIANVS AVG COS III P P. Reverse: Hadrian standing [in `archaic oriental victor pose´] right on crocodile, holding spear and parazonium. Strack ([1933] Hadrian) / Die Reichspraegung zur Zeit des Hadrian (291) RIC2 / The Roman imperial coinage, vol. 2: Vespasian to Hadrian (294 corr, p. 373) RIC2.3 / The Roman Imperial Coinage, vol. II - part 3 from AD 117-138 Hadrian (1441)". Cf. P. Karanastasi 2012/2013, 353 with ns. 178, 191, Abb. 7. Courtesy of the British Museum, London.

© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

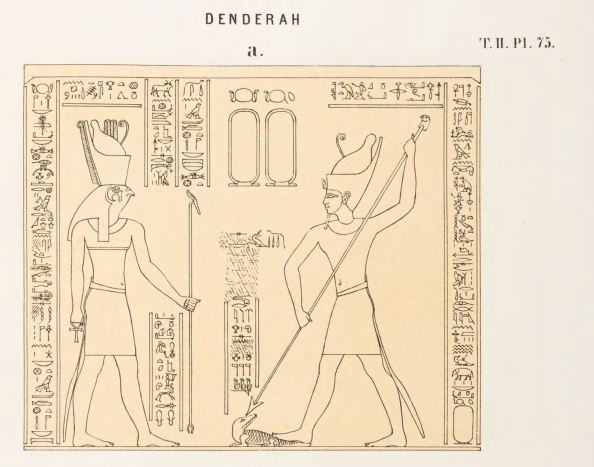

Fig. 129.1. Drawing after a relief from the Temple of Hathor at Dendera in Egypt, which represents a Pharaoh in the iconography of `Horus killing the crocodile´. From: A.E. Mariette, Dendérah, vol. II (1870-1874), Pl. 75a; cf. A.C. Levi (1948, 35, Fig. 5).

Fig. 130. Sestertius, issued by Vespasian in Rome in AD 71: IVDAEA CAPTA. Obverse: Portrait of Vespasian, laureate, to right. Inscription: IMP CAES VESPASIAN AVG P M TR P PP COS III. Reverse: palm tree, to left: Vespasian, standing right in `victor pose´ and wearing a cuirass, holding with his right hand a spear, and with his left hand a parazonium, his left foot set on a helmet; to the right of the palm tree: seated Judaea. Inscriptions: IVDAEA CAPTA and SC (RE2 / Coins of the Roman Empire in the British Museum, vol. II: Vespasian to Domitian (543, p. 117) RIC2.1 / The Roman Imperial Coinage, vol. 2 part 1: From AD 69 to AD 96: Vespasian to Domitian (167, p. 71). Courtesy of the British Museum, London. Online at: <https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/C_R-10518>. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

On 31st October 2024, John Pollini was kind enough to send me a jpeg-file and the Link to a copy of this coin (here Fig. 130), which is much better preserved than the above-mentioned copy in the British Museum, and is owned by the American Numismatic Society; cf. <https://numismatics.org/collection/1944.100.39981>.

I also thank Franz Xaver Schütz, who, on the same day, found out in a special research on the Internet, that this is the only known copy of this coin, on which the point of Vespasian's spear, which is turned downwards, is actually visible, and that very well (!).

Fig. 130. Bronze sestertius, issued by Vespasian in Rome in AD 71: IVDAEA CAPTA. Obverse: Portrait of Vespasian, laureate, to right. Inscription: IMP CAES VESPASIAN AVG P M TR P PP COS III. Reverse: palm tree, to left: Vespasian, standing right in `victor pose´ and wearing a cuirass, holding with his right hand a spear with its visible point turned downwards, and with his left hand a parazonium, his left foot set on a helmet; to the right of the palm tree: seated Judaea. Inscriptions: IVDAEA CAPTA and SC (RE2 / Coins of the Roman Empire in the British Museum, vol. II: Vespasian to Domitian (543, p.117) RIC2.1 / The Roman Imperial Coinage, vol. 2 part 1: From AD 69 to AD 96: Vespasian to Domitian (167, p. 71). Courtesy of the The American Numismatic Society.

Online at: <https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/coins-from-judaea-capta> [On 5th October 2024, this URL was not accessible any more].

The British Museum, RIC II, Part 1 (second edition) Titus 502: "Mint: uncertain value; Region: Europe - Thrace". Obverse: "Head of Titus, laureate, to right. Inscription: IMP T CAES DIVI VESP F AVG P M TR P P P COS VIII". Reverse: Titus, standing in `victor pose´ and wearing a cuirass, "holding spear and parazonium, resting foot on helmet, standing to left of palm tree; Judaea seated right on cuirass; Inscriptions: IVDAEA CAPTA and SC". Courtesy of the British Museum, London. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

Fig. 131b. Sestertius, issued by Vespasian in Rome in AD 72. Obverse: Head of Titus, laureate, to right. Inscription: "T CAES VESPASIAN IMP PON TR POT COS II". Reverse: Titus, standing right in `victor pose´ and wearing a cuirass to the left of a palm tree, "holding spear in right hand and parazonium in left hand, foot on helmet; to right, Judaea seated right. Inscriptions: IVDAEA CAPTA SC". The British Museum, Museum number R. 10570 (RE2 / Coins of the Roman Empire in the British Museum, vol. II: Vespasian to Domitian (631, p. 140) RIC2.1 / The Roman Imperial Coinage, vol. 2 part 1: From AD 69 to AD 96: Vespasian to Domitian (422, p. 87). Courtesy of the British Museum, London. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

Fig. 131c. Sestertius, issued by Titus in Rome in AD 80-81. Obverse: Portrait of the divinized Vespasian, laureate, to right. Inscription: "DIVVS AVGVSTVS VESPASIAN PATER PAT". Reverse: "Palm tree; to left, captive standing right; to right, Judaea seated right on cuirass, head on hand; both surrounded by arms; Inscriptions: IVDAEA CAPTA and SC". The British Museum, Museum number 1974,0518.1 (RIC2.1 / The Roman Imperial Coinage, vol. 2 part 1: From AD 69 to AD 96: Vespasian to Domitian (369, p. 221). Courtesy of the British Museum, London. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

Fig. 142. Aureus, issued by the Emperor Hadrian in AD 117 in Rome. RIC 3 (p. 237, Hadrian 5, pl. 46.3). Trajan gives Hadrian the globe of `world rule´. Cf. Stack's Bowers and Ponterio Sixbid Numismatic Auctions The January 2013 N.Y. I.N.C Session I Lot 5001 11. Jan. 2013 [on 21st November 2024, this URL was not accessible any more]: "Among the earliest coinage issues of Hadrian, it depicts a youthful beardless portrait of the emperor. The reverse type depicts Trajan and Hadrian clasping hands, with "ADOPTIO" in the exergue. This directly references Hadrian's adoption by Trajan, testifying to Hadrian's legitimacy as the new emperor of Rome"... "`IMP. CAES. TRAIAN. HADRIANO OPT. AVG. GER. DAC´. Laureate, draped and cuirassed bust of Hadrian right. Reverse: `PARTHIC. DIVI TRAIAN. AVG. F. P.M. TR. P. COS. P.P. ADOPTIO´. Trajan and Hadrian standing, facing each other, clasping right hands". - Contrary to this description, comparisons with the portraits of Hadrian on the aurei here Figs. 145; 146 show that also this coin represents Hadrian bearded.

Courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Online: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b104274528 (21.11.2024)

Tempel des Divus Vespasianus (Photos: FX Schütz).

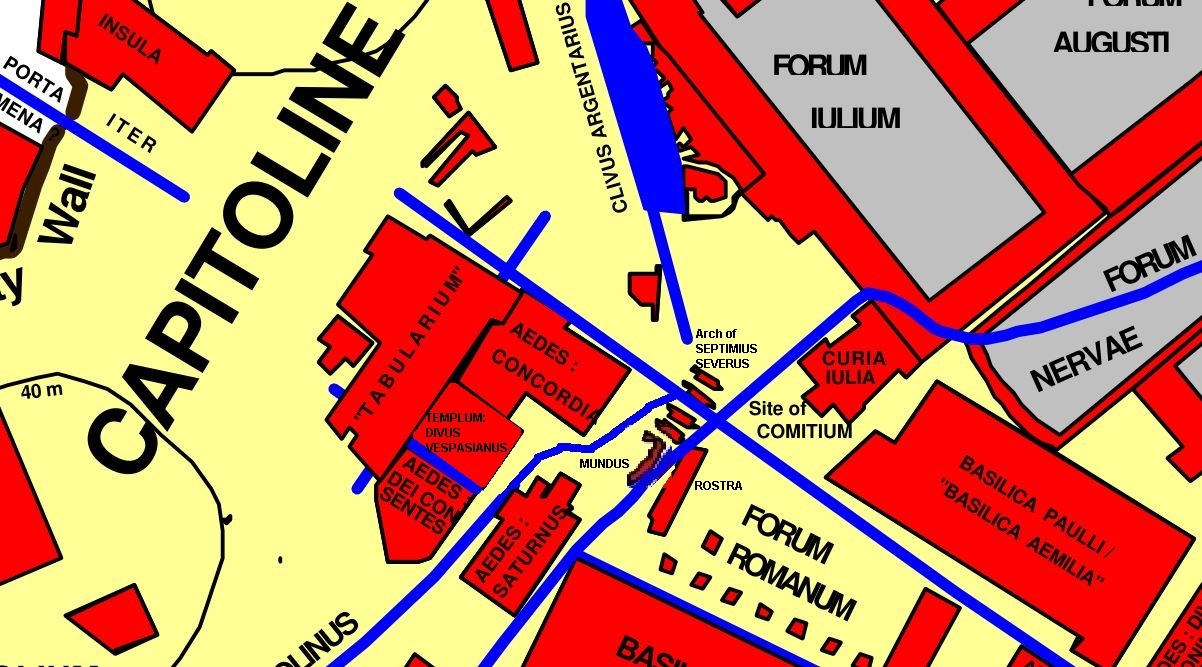

Fig. 58: Karte des Forum Romanum (Detail), mit dem Tempel des Divus Vespasianus. C. Häuber und F.X. Schütz, "AIS ROMA" (2022).

This text, a discussion of the Preview, "Ehrenstatue für Hadrian in Rom für die Niederschlagung des Bar Kochba-Aufstandes" belongs to FORTVNA PAPERS vol. III-2,

Appendix IV.c.2.) The Ogulnian monument (a statue group representing the she-wolf suckling Romulus and Remus, standing underneath the sacred fig tree ficus Ruminalis), and the she-wolf suckling Romulus and Remus on a headless cuirassed statue of a Flavian emperor (Domitian?) in the Vatican Museums (cf. here Fig. 6, right) and on Hadrian's cuirassed statue from Hierapydna at Istanbul (cf. here Fig. 29). Exactly like the statue of the ficus Ruminalis on the Anaglypha Hadriani (cf. here Figs. 21; 22), the lupa and the twins on those cuirasses symbolize Rome's claim to eternal power and divine mission, and that it was the task of the Roman emperor to fulfill this obligation (cf. C. Parisi Presicce 2000, 28, 29). With a discussion of the meaning of the lupa and the twins on the "Rilievo Terme Vaticano" (cf. here Fig. 31), and with The second Contribution by Claudia Valeri

... To conclude this survey: very different occasions have so far been suggested for the creation of the series of statues that resemble Hadrian's portrait-statue from Hierapydna (cf. here Fig. 29): shortly after AD 117, after 121, after 131/132, around 132-135, or after Hadrian's divinization.

Parisi Presicce (2000, 29, quoted verbatim infra) suggests that these statues could have been commissioned by the magistrates of the towns in question soon after Hadrian's divinization. Birgit Bergmann (2010b) believes this statue-type was created after Hadrian's foundation of the Panhellenion 131/132 and was especially frequently copied in connection with Hadrian's victory in the Bar Kokhba Revolt (132-135 or 136). As we shall see below, this was followed by Michaela Fuchs (2014), who suggests that the iconography of the original statue-type was appropriately adjusted to the new purpose.

Cornelius Vermeule was first to suggest that the statue from Hierapydna (here Fig. 29) commemorates Hadrian's victory in the Bar Kokhba Revolt (132-135 or 136); cf. Vermeule (Art of Antiquity, Volume Four, Part Two. Jewish Relations with the Art of Ancient Greece and Rome (``JVDAEA CAPTA SED NON DEVICTA´´) 1981, pp. 24-25, quoted verbatim supra, in volume 3-1, p. 918).

Vermeule's findings were overlooked by (almost) all the other scholars discussed here.

My thanks are due to Hans Rupprecht Goette, who alerted me to Vermeule's publication (1981), after I had finished writing this Appendix IV.2.c). Later I decided to `cut out´ from this Appendix the text, which became the separate Study on Hadrian's portrait-statue from Hierapydna in volume 3-1, pp. 899-959.

Matteo Cadario (2004) prefers an earlier date, namely sometime after AD 121, and sees a connection with Hadrian's travels in Greece (AD 121-125). Pavlina Karanastasi (2012/2013, 381), on the other hand, believes that this series of statues was created even earlier than that, in response to "repercussions of the uprising of the Jews of the Diaspora, which had broken out under Trajan in AD 116/7", and which, as we have learned above from Goette (2019, 2, quoted verbatim supra, at Appendix IV.c.1.). Post Scriptum: Hadrian's situation in AD 117-118), Hadrian had only to deal with as late as in August of AD 117 Trajan had fallen ill and decided to leave the Levant for Rome.

Karanastasi (2012/2013, 342-348, Section: "Der Aufstand der Juden in der Diaspora") discusses this uprising of the Jews in the diaspora, seen from the perspective of the people, who lived in the island of Crete, who had commissioned the many statues of this `Hadrian series´ found there.

But as we have seen above, in Parisi Presicce's discussion of those statues (here Fig. 29), examples of them have also been found elsewhere; cf. Parisi Presicce (2000, 25-30), on the now almost 30 `replicas´ of Hadrian's portrait-statue from Hierapydna at Istanbul, who notes that they are not faithful copies of one prototype in the true sense of the word. For a discussion of this fact in detail; cf. Birgit Bergmann (2010b, 230-235); and Pavlina Karanastasi (2012/2013, 334).

See also Karanastasi (2012/2013, 325-332; cf. pp. 358-363, cat. nos. 1-29). Cf. pp. 358-365: her cat. nos. 1-22 are, in her opinion, certain replicas of this statue-type; cf. pp. 365-366: her cat. nos. 23-24 possibly belong to this statue-type; cf. pp. 366-367: her cat. nos. 25-29 probably do not belong to this statue-type.

Before discussing the hypothesis of Karanastasi (2012/2013, 342-348) concerning her suggestion that the series of portrait-statues of Hadrian (cf. here Fig. 29) `were a response to the uprising of the Jews in the Diaspora shortly after 116/117 AD´, I will anticipate a summary of the results of my telephone- and E-mail-conversations with several colleagues and friends concerning this matter.

My correspondence with Hans Rupprecht Goette dates from 6th October-8th November 2024. The following summary of my research (published supra, in volume 3-1; to which I have now added many new observations supporting my dating of this statue) from 14th October-14th November. This correspondence began, when I sent Hans the Link to the Preview to FORTVNA PAPERS volume III-2 on our Webserver, of the "Ehrenstatue für Hadrian in Rom für die Niederschlagung des Bar Kochba-Aufstandes (132-135 oder 136 n. Chr.)", in which I discuss the portrait of Hadrian from Hierapydna (here Fig. 29). Online at: <https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Hadrian_Ehrenstatue_in_Rom.html>.

Because Hans wrote me that he does not agree with my `late´ dating of this portrait of Hadrian (Fig. 29) - he himself dates it to circa AD 120 - I have summarized below my arguments for this suggestion. In the course of this correspondence with Hans, and after discussions with Franz Xaver Schütz (13th October-12th November); with Lorenzo Cigaina (15th October-14th November), with Eberhard Thomas (25th October-9th November), with Eric M. Moormann (28th October-10th November), with John Pollini (14th-October-9th November), and with Peter Herz (October-November), all of whom I sent the Preview on the "Ehrenstatue", and also this manuscript, I have realized now more clearly than before that Karanastasi's hypotheses (2012/ 2013) are based on some (erroneous) assumptions.

First of all, I am not convinced of Karanastasi's (2012/2013) explanation, why so many portraits of Hadrian of the `Hierapydna-type´ (five or even six?; cf. here Fig. 29) have been dedicated in Crete.

As will be discussed in detail in the following, Karanastasi (2012/2013) explains the dedications of those many portraits of Hadrian in Crete as responses to the Revolt of the Jews in the diaspora (AD 116-117). But let me before anticipate here the results of my own research that will be summarized below:

I myself explain the dedications of those portraits of Hadrian in Crete (cf. here Fig. 29), following the hypotheses of Lorenzo Cigaina (2020, 221-222, § IV.6, quoted verbatim infra). Cigaina suggests that Hadrian (in AD 133-136) had improved a pre-existing road that connected the western part of Crete with its eastern part. Cigaina, therefore, convincingly suggests that Hadrian used this road to guarantee the transportation of soldiers and supplies that Hadrian needed for his suppression of the Bar Kokhba Revolt in Judaea (AD 132-135 or 136). In Cigaina's opinion, all the replicas of this statue-type of Hadrian (here Fig. 29) are datable to AD 132-138; and that they were, therefore, dedicated to commemorate Hadrian's suppression of the Bar Kokhba Revolt. Cigaina's hypotheses are corroborated by the date and by the iconography of Hadrian's coins (cf. here Fig. 129, above; Fig. 129, below, left; 129, below, right). Those coins of Hadrian represent, in my opinion, the prototype of Hadrian's portrait-statue from Hierapydna (here Fig. 29, and of its replicas), and because those coins were issued in Rome, this prototype stood there.

As also Karanastasi agrees (2012/2013; cf. below, and infra, in Post Scriptum, at point 5.)), these coins, issued by Hadrian in Rome, show on their reverses a statue strikingly similar to Hadrian's portrait-statue from Hierapydna (here Fig. 29). Those coins are dated in the catalogues of the British Museum to `AD 130-138´. Peter Franz Mittag (Römische Medaillen Caesar bis Hadrian, 2010, 48) dates those coins to: "vor 132(?)-138(?) n. Chr.". I thank Peter Herz for the reference. I myself assume that Hadrian issued those coins in Rome in AD 136 (for a discussion; cf. infra, in Post Scriptum, at point 3.)).

Karanastasi (2012/2013, 352-353; cf. also p. 324 with n. 4, p. 356 with n. 191 (both text-passages quoted verbatim infra), Fig. 7. London, Brit. Mus. Inv. 1972.0711.4: Silbersesterz Hadrians [= here Fig. 129, below, right]), publishes one of those coins, which she dates to `AD 128-138´.

But Karanastasi (2012/2013, 353, with n. 178, p. 356 with n. 191) does not consider the date of this coin Fig. 129, below, right (`AD 128-138´) in her discussion of the question, on which occasion the portrait-statue of Hadrian from Hierapydna (here Fig. 29; and its replicas in Crete) could have been dedicated.

Let's now turn to Karanastasi's hypotheses in detail:

As was discussed above, in this Appendix IV.c.2.), Karanastasi (2012/2013, 342-348, Section: "Der Aufstand der Juden in der Diaspora") writes (on page 348): "Dass die ›Feinde‹ in diesem historischen Moment für die Insel [i.e., Crete] keine anderen als die aufständischen Juden in der Diaspora sein konnten, scheint im Licht der geschilderten Ereignisse über jeden Zweifel erhaben".

I have in this context commented on Karanastasi's (2012/2013) observations as follows: ``Karanastasi (2012/2013) suggests that the portraits of Hadrian of her `eastern type´, of which, apart from the statue discussed here [i.e., Hadrian's portrait-statue from Hierapydna; here Fig, 29], also many other replicas were found in Crete, were dedicated as Loyalitätsadressen [to Hadrian] in response to the uprisings of the Jews in the diaspora [which she dates: AD 116-117] inter alia in Cyrene, a Roman province that was closely connected to Crete, since the capital of the province Creta et Cyrenae, with the residence of its proconsul, was Gortyn in Crete; cf. Cavalieri and Jusseret (2009, 357); and Karanastasi (2012/2013, 347 with n. 145)´´.

Whereas Karanastasi (2012/2013, 342-348, Section: "Der Aufstand der Juden in der Diaspora") discusses the Revolt of the Jews in the diaspora (AD 115-117) in more detail, she only mentions the Great Jewish Revolt or War (AD 66-73) on p. 346 with n. 137, and the Bar Kokhba Revolt (AD 132-135 or 136), on p. 342 with n. 105, p. 346 with n. 137, and on p. 350, with n. 167.

Based on different parts of the immense available research on those subjects than that consulted by Karanastasi (2012/2013), all those uprisings of the Jews are here dealt with in great detail; see below, in this Appendix IV.2.c).

In this research, I have followed the methodological approach of the military historian Rose Mary Sheldon (Spies of the Bible. Espionage in Israel from the Exodus to the Bar Kokhba Revolt, 2007), to whom this book is dedicated. She starts her research with the Maccabean Revolt (167-163 BC), and describes all those above-mentioned conflicts from the perspective of the Jews and of the Romans alike. It thus became also evident for me in the course of my own studies that all those uprisings of the Jews against the Romans are interrelated. In addition, I follow those scholars, who have suggested that the Emperor Trajan (and his natural father, Traianus pater) had caused the Revolt of the Jews in the diaspora, whereas it was the Emperor Hadrian, who caused the Bar Kokhba Revolt. What is less well known: the Emperor Nero had himself, if not caused the Great Jewish Revolt, at least "helped to precipitate the great insurrection of 66"; cf. Howard Hayes Scullard ("Gessius Florus", in: OCD3 [1996] 635); cf. supra, in volume 3-1, pp. 192-193.

The Bar Kokhba Revolt lasted from AD 132-135; cf. Rose Mary Sheldon (2007, 179-199, "Chapter 8 Israel's Last Stand - The Bar Kokhba Revolt"; cf. Werner Eck (2007); Werner Eck and Andreas Pangerl (2008, 385 with n. 72). According to Werner Eck (2019b, 201 with n. 34; and id. 2022, Sp. 486; and according to D. KIENAST, W. ECK and M. HEIL 2017, 123: it lasted until AD 136 instead). For a discussion of this point; cf. supra, in volume 3-1, p. 959.

There is no doubt, as also Karanastasi stresses (2012/2013, 342-348, Section: "Der Aufstand der Juden in der Diaspora"), that the Emperor Hadrian tried very hard to improve the situation in those parts of the Roman Empire that had greatly suffered from the Revolt of the Jews in the diaspora (AD 115-117).

This Appendix IV. is, after all, inter alia dedicated to a study of the here-so-called Anaglypha Hadriani (here Figs. 21; 22), one of which is called `the burning of debt records´ relief (here Fig. 22):

Appendix IV. D. Filippi (1998) has convincingly identified the `first gate of the Capitolium´ (Tac., Hist. 3,71,1-2) with the remains of an arch, excavated by A.M. Colini in the 1940s, with the Porta Pandana, and with the arch, visible on the `burning of debt records´ relief of the here-so-called Anaglypha Hadriani (Figs. 21; 22). With some new ideas concerning the Anaglypha Hadriani; and discussions of the colossal statue of Hadrian (now Constantine the Great) in the courtyard of the Palazzo dei Conservatori (cf. here Fig. 11); of the inscription (CIL VI 974 = 40524; cf. here Fig. 29.1), belonging to a statue of Hadrian; of two headless cuirassed statues of Flavian emperors (Titus or Vespasian? and Domitian?) in the Vatican Museums (cf. here Fig. 6, left and right) and of Hadrian's cuirassed statue from Hierapydna at Istanbul (cf. here Fig. 29).

On this `burning of debt records´ relief (here Fig. 22) is represented the burning of debt records, kept at the aerarium populi Romani, on the Forum Romanum in Rome. This event had occurred shortly after Hadrian had returned to the City as the new emperor on 9th July of AD 118. The debt records in question, comprising also many of the fiscus (that were instead burnt on the Forum of Trajan), had amounted to altogether 900.000.000 sestertii (!). But contrary to what was earlier believed, Hadrian did this by no means for the poor all over the Empire, but rather for the rich, as Peter Herz has been able to demonstrate, and thus in order to improve his own precarious situation.

In the following, I repeat, therefore, what has already been said above; cf. supra, at Appendix IV.b):

``After having finished writing this entire Appendix IV., I had again, beginning with the 11th November 2020, the chance to discuss the whole matter with Peter Herz in several telephone- and E-mail conversations.

Herz alerted me to the fact that Hadrian ordered the destruction of the debt records of the fiscus, recorded by Cassius Dio (69,8,1 2 ) and by the Historia Augusta (Hadr. 7,6), because of very different reasons than those that have been suggested so far. The debtors of the fiscus were by no means the poor all over the Empire, but instead the rich. Since it was the goodwill of those, which Hadrian needed desparately because of his own precarious situation at the beginning of his reign.

This was caused by a variety of reasons: because of Hadrian's lack of legitimization, because he had ordered the assassination of four consulares, and because he, at the very beginning of his reign, had immediately given up some of Trajan's recently conquered provinces in the East and in the Balkans.

Besides, as Herz has informed me as well, the debts at the fiscus, which those documents recorded, could not possibly be payed back, because many of the debtors had for example been the tenants of imperial domains in Egypt, the Cyrenaica and in Cyprus, that is to say, in those Roman provinces that had been greatly devastated in the course of the Revolt of the Jews in the diaspora. The emperor's relevant benefactions were thus the immediate results of the Revolt of the Jews in the diaspora, from which Hadrian had just come back in AD 118 [my emphasis]´´.

See for a detailed discussion of all this, supra, in volume 3-1, pp. 1281-1282, at The third Contribution by Peter Herz: Der Übergang von Trajan auf Hadrian und das erste Regierungsjahr Hadrians.

The just-mentioned `assassination of the four consulares´ at the beginning of Hadrian's reign, shows another difference between Karanastasi's approach to describe the historical situation shortly after AD 117 and the one presented here: Karanastasi (2012/2013, 343-345) mentions the important rôle of Marcius Turbo in the suppression of the Revolt of the Jews in the diaspora (inter alia in Egypt) under Trajan. To this we may now add Peter Herz's account (cf. supra, in volume 3-1, p. 1276), who mentions, in addition to Turbo's actions under Trajan, also those under Hadrian, which served again the purpose of improving Hadrian's own precarious situation.

Peter Herz (supra, in volume 3-1, p. 1280) writes about those four consulares, who had been killed at the beginning of Hadrian's reign:

"SHA Hadr. 7.2: quare Palma Terracinis, Celsus Baiis, Nigrinus Faventinae, Lusius in itinere senatus iubente, invito Hadriano, ut ipse in vita sua dicit, occisi sunt.

``Deswegen wurde Palma in Tarracina, Celsus in Baiae, [Avidius] Nigrinus in Faventia, Lusius [Quietus] auf dem Weg (wohin ist unbekannt) auf Anordnung des Senates und gegen den Willen Hadrians, wie er selbst in seiner Autobiographie sagt, getötet.´´".

Herz (supra, in volume 3-1, p. 1276) writes about Lusius Quietus and Marcius Turbo:

"Hadrian erreichte die Nachricht vom Tode Trajans (und seiner Adoption auf dem Sterbebett) wahrscheinlich am 11. August 117 in Antiochia. Seine wohl erste Personalentscheidung war die Ablösung von Lusius Quietus von der Position des legatus Augusti Iudaeae. Quietus scheint sich dann zusammen mit seinen maurischen Stammeskriegern in Richtung Mauretanien begeben zu haben ... Kurze Zeit danach wurde Marcius Turbo, der bisher in seiner Eigenschaft als praefectus classis praetoriae Misenensis gegen die noch nicht endgültig unterworfenen jüdischen Aufständischen in Ägypten eingesetzt gewesen war, dort abgezogen und mit der Masse seiner Truppen nach Mauretanien gesandt, wo zwischenzeitlich die Stammeskrieger des Quietus rebelliert hatten".

Cf. supra, in volume 3-1, p. 1283, "Note by the editor Chrystina Häuber"):

"Cf. most recently for "Lusius Quietus, der Statthalter in Iudaea ... einer der Teilnehmer der angeblichen Verschwörung der vier Konsulare gegen Hadrian", likewise mentioned by Peter Herz: Werner Eck (2022b, 231; cf. p. 227 with n. 14)".

Secondly, I do not agree with Karanastasi concerning her interpretation of the representation on Hadrian's cuirass.

Karanastasi (2012/2013, 338, 381, both text-passages quoted verbatim supra) asserts that the Palladion, represented on the cuirass of Hadrian's portrait-statue from Hierapydna (here Fig. 29), should instead be identified with the Athena Promachos; she regards this (alleged) fact as an argument for her early dating of this portrait of Hadrian. In reality, Karanastasi's assertion, which she bases on some further (erroneous) assumptions, is not true, as already observed by Michaela Fuchs (2014, 127, n. 24, quoted verbatim supra, in volume 3-1, pp. 903-905):

"Für eine frühe Entstehung des Panzerschmucks [of Hadrian's portrait-statue here Fig. 29] spricht sich jetzt auch Karanastasi 2012-2013, 338 aus und beruft sich auf Prägungen, die seit 121 bzw. [beziehungsweise] 119 n. Chr. das Bild der Lupa Romana bzw. [beziehungsweise] der Athena Promachos, wie sie das Palladion deutet (S. 332-333), zeigen. Beide Motive begegnen jedoch auch schon viel früher und können als Einzelbilder natürlich nicht für die Datierung der Komposition am Panzerschmuck herangezogen werden".

Karanastasi writes concerning the date and iconography of those coins, which Hadrian issued in Rome (Fig. 129, above; Fig, 129, below, left; Fig, 129, below, right), on which, in my opinion, the prototype appears, after which the portrait of Hadrian from Hierapydna (Fig. 29, and its replicas) were copied;

cf. Karanastasi (2012/2013, 352-353, with Fig. 7. London, Brit. Mus. Inv. 1972.0711.4: Silbersesterz Hadrians [= here Fig. 129, below, right]):

"Sucht man nun nach einem konkreten freiplastischen Vorbild bzw. nach einem Vermittler für diese Werke [which she has discussed before], bieten sich als beste Kandidaten [page 353] die Hadrianstatuen aus Kreta im ›östlichen Typus‹ an, zuvorderst die Statue aus Hierapytna [cf. here Fig. 29], die nach orientalischem Habitus den Fuß auf den geschlagenen Feind setzt [with n. 177, providing references]. Die enge Verbindung des statuarischen Schemas der zuletzt genannten Figur mit Ägypten wird durch eine in die Spätzeit Hadrians datierte stadtrömische Prägung noch deutlicher (Abb. 7 [= here Fig. 129, below, right]): der Kaiser, der in einer zum Verwechseln ähnlichen Pose und mit den gleichen Attributen wie die Statue aus Hierapytna dargestellt ist, setzt den Fuß auf das Zeichen von Ägypten, das Krokodil [with n. 178; my emphasis]".

To Karanastasi's (2012/2013, 353) just-quoted passage, I should like to add some comments.

The crocodile is here (i.e., on the coins here Fig. 129, above; Fig. 129, below, left; Fig. 129, below, right) not predominantly "das Zeichen von Ägypten" (`a symbol of Egypt´), as Karanastasi (2012/2013, 353) asserts, who mentions in her note 178 (referring to her note 191) the article by Annalina Calò Levi (1948). Levi quoted in this text Paul Leberecht Strack (1933), who already then had (correctly) characterized the meaning of the crocodile "as a symbol of ... the enemy in general", as Levi (1948, 31) wrote. Karanastasi (2012/2013, 356, n 191, quoted verbatim infra) quotes "Levi 1948" for this statement, but ignores the fact that this was Strack's (1933) interpretation of this crocodile.

We have already heard that the same interpretation of the crocodile, as that suggested by Strack (1933, 138) has, in the meantime, also been provided by the Egyptologist Emanuele M. Ciampini (2016):

"Levi (1948, 35, Fig. 5) bildet ein Relief im Hathor-Tempel von Dendera in Ägypten ab, das einen Pharao als Horus zeigt, der ein Krokodil tötet (hier Fig. 129.1), und stellt zu Recht fest, dass Hadrians Münze (hier Fig. 129, above) den Kaiser somit `als Horus´ zeigt, mit dem die ägyptischen Pharaonen identifiziert wurden: `Hadrian as King of Egypt´ lautet deshalb der Titel ihres Aufsatzes.

Dargestellt ist somit auf diesem Relief (hier Fig. 129.1) die Hauptaufgabe des ägyptischen Pharaos: Die Etablierung der (sozialen) Harmonie in seinem Herrschaftsbereich, Ma'at genannt, ein Idealzustand, den nach ägyptischer Vorstellung nur der regierende Pharao herbeiführen konnte, und der es nötig machte, dass der König `das Böse bzw. [beziehungsweise] das Chaos bekämpfte´; vergleiche Emanuele M. Ciampini (2016, S. 115-116, mit Anm. 4) (s.o., in Band 3-1, S. 29-30, 909, 915-923; und oben, im Appendix II.) [my emphasis]";

cf. <https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Hadrian_Ehrenstatue_in_Rom.html>.

Annalina Calò Levi (1948, 31) wrote: "Strack [with n. 4] also believes the type [i.e., the coins here Fig. 129, above; Fig. 129, below, left; Fig. 129, below, right] to be not earlier than A.D. 134 ... Strack's explanation excludes a reference to Hadrian's journey to Egypt. The motive, in his opinion, is a victory motive; but he queries whether the crocodile might not be a symbol of Palestine or of the enemy in general". In her n. 4, Levi quoted: P.L. Strack (1933, 138).

See also above, in volume 3-1, p. 920: Paul Leberecht Strack (1933, 138) wrote that the crocodile [on the coins here Fig. 129, above; Fig. 129, below, left; Fig. 129, below, right] symbolizes ""``das Gefährliche und Feindliche schlechthin´´ ... oder [das] auch als Symbol für Palästina verstanden werden kann [with n. 43]". Cf. Michaela Fuchs (2014, 130, quoting in her n. 43: P.L. STRACK 1933, 138).

Karanastasi (2012/2013) dates Hadrian's portrait-statue from Hierapydna (here Fig. 29; and its replicas) `early´, that is to say, as honorary statues, dedicated to Hadrian as Loyalitätsadressen in response to the uprisings of the Jews in the diaspora, which, in her opinion, lasted from AD 116-117.

In doing so, Karanastasi does not consider the following facts in her reasoning:

a) already Strack (1933, 138) had written that Hadrian could not possibly have issued those coins (here Fig. 129, above; Fig. 129, below, left; Fig. 129, below, right) in Rome `before AD 134´. Karanastasi herself (2012/2013, 356, n. 191) illustrates the coin here Fig. 129, below, right, as her Fig. 7, and dates this coin as follows: `AD 128-138´ (see below). Nor does Karanastasi mention the fact -

b) that Strack (1933, 138) had suggested - obviously because of the date of those coins - that this crocodile (here Fig. 129, above; Fig. 129, below, left; Fig. 129, below, right) could also `have been a symbol for [a victory over] Palestine´. Nor does Karanastasi consider the facts -

c) that Annalina Calò Levi (1948, 31) had not only followed Strack (1933, 138) concerning point a) and point b), but -

d) that Levi (1948), concerning those coins (here Fig. 129, above; Fig. 129, below, left; Fig. 129, below, right), had been of the following opinion. Levi (1948, 30-31, 38 with n. 36) believed that the cuirassed portrait-statue of Hadrian, which appears on the reverses of those coins, must have been erected in Rome, suggesting that this statue of Hadrian had been dedicated - after AD 134 - at the cenotaph of Antinous, which she located at the Mausoleum of Hadrian/ Castel Sant'Angelo (cf. here Fig. 58, labels: Tomb of the Emperor Hadrian/ SEPULCRUM: P. AELIUS HADRIANUS / Castel S. Angelo); cf. supra, in volume 3-1, pp. 929, 944-946.

For a summary for this entire complex of subjects; cf. supra, in volume 3-1, p. 920; cf. pp. 899-900.

As a logical consequence of points a) - d) we may, in my opinion, therefore, conclude the following:

that the copies of this statue of Hadrian, dedicated in Rome (and represented on the coins here Fig. 129, above; Fig. 129, below, left; Fig. 129, below, right), for example, in my opinion, his portrait-statue from Hierapydna (here Fig. 29) could only have been commissioned after the original statue of Hadrian in Rome had been dedicated. As already mentioned, Annalina Calò Levi (1948, 30-31, 38 with n. 38) had dated this statue of Hadrian in Rome, following Strack's (1933, 138) suggestion, to `after AD 134´.

Fortunately we have those coins (here Fig. 129, above; Fig. 129, below, left; und Fig. 129, below, right), on which this statue of Hadrian in Rome is represented. All four coins with the representation of this iconography on their reverses, owned by the British Museum, London, are dated in the catalogues of this museum as follows: "AD 130-138". For the list of those four coins;

cf. <https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Hadrian_Ehrenstatue_in_Rom.html>.

Hadrian's coins (here Fig. 129, above; Fig. 129, below, left; und Fig. 129, below, right) carry the inscription "HADRIANVS AVG COS III PP"; according to Peter Franz Mittag (2010, 48), Hadrian's coins with this inscription were minted: "vor 132(?)-138(?) n. Chr.". To my own dating of those coins: `AD 136´, I will come back below (cf. infra, in Post Scriptum, at point 3.)).

I am, therefore, wondering, why Karanastasi (2012/2013) has suggested this `early dating´ of the portrait of Hadrian from Hierapydna (and of its replicas) at all: that is to say: `shortly after AD 117´, since she herself, as we have just seen, writes the following (on p. 353):

"Die enge Verbindung des statuarischen Schemas der zuletzt genannten Figur [= Hadrian's portrait from Hierapydna; here Fig. 29] mit Ägypten wird durch eine in die Spätzeit Hadrians datierte stadtrömische Prägung noch deutlicher (Abb. 7 [= here Fig. 129, below, right]): der Kaiser, der in einer zum Verwechseln ähnlichen Pose und mit den gleichen Attributen wie die Statue aus Hierapytna dargestellt ist, setzt den Fuß auf das Zeichen von Ägypten, das Krokodil [with n. 178]".

As already said, all four coins, issued by Hadrian with this iconography on the reverses (cf. here Fig. 129, above; Fig. 129, below, left; Fig. 129, below, right), which are owned by the British Museum, are dated in the catalogues of this museum to `AD 130-138´. One of those four coins, illustrated by Karanastasi (2012/2013, 356, n. 191) as her Fig. 7 (= here Fig. 129, below, right), she herself dates, as already mentioned above: "zwischen 128 und 138" n. Chr. (`between AD 128-138) (!).

Karanastasi (2012/2013, 353) writes in her note 178: "Zum Münzbild und zu dessen Deutung s. u. Anm. 191".

Karanastasi (2012/2013, 356) writes in her note 191: "Sesterz (AR) London, Brit. Mus. Inv. 1972,0711.4 [= here Fig. 129, below, right]: Strack 1933, 138 Nr. 291 Taf. IV; BMCRE III (1936) S. cIxxxii; 475 Nr. 1552. 1553 Taf. 89, 2; 485 Nr. 167 Taf. 91, 3; Levi 1948. Aufgrund der Legende PP (pater patriae) ist die Prägung zwischen 128 und 138 zu datieren. Dass hier Hadrian als König von Ägypten, Inkarnation des Horus und Überwinder feindlicher Kräfte, die das Krokodil verkörpert, dargestellt ist, wurde treffend durch Levi (1948, 36 f.) dargelegt. Vgl. [vergleiche] La Rocca 1995, 231 und Laubscher 1996, 236 mit Anm. 54, der zu Recht hervorhebt, dass römische Betrachter das Bild auch ohne Kenntnis des ägyptischen Hintergrunds verstehen konnten [my emphasis]".

To this I will come back below (cf. infra, in Post Scriptum, at point 5.)).

Karanastasi (2012/2013) does not consider the contributions by Egyptologists to the discussion of the `archaic oriental victor pose´ of Hadrian's portrait-statue from Hierapydna (here Fig. 29). As already said, Hadrian appears also on the reverses of his coins in this iconography (cf. here Fig. 129, above; Fig. 129, below, left; Fig. 129, below, right).

For the contributions by Egyptologists to the discussion of this iconography; cf. supra, in volume 3-1, pp. 29-30, 909-911, 915-923; and above, in Appendix II.

When Karanastasi's article (2012/2013) appeared, the results of Sam Heijnen's (2020) research on the decoration of Hadrian's cuirass of his portrait-statue from Hierapydna (here Fig. 29), and of its replicas, were not yet known. My thanks are due to Hans Rupprecht Goette, who was kind enough to send me Sam Heijnen's publication; cf. supra, in volume 3-1, pp. 927-929, at The observations concerning Hadrian's portrait-statue from Hierapydna by Sam Heijnen (2020); cf. p. 943.

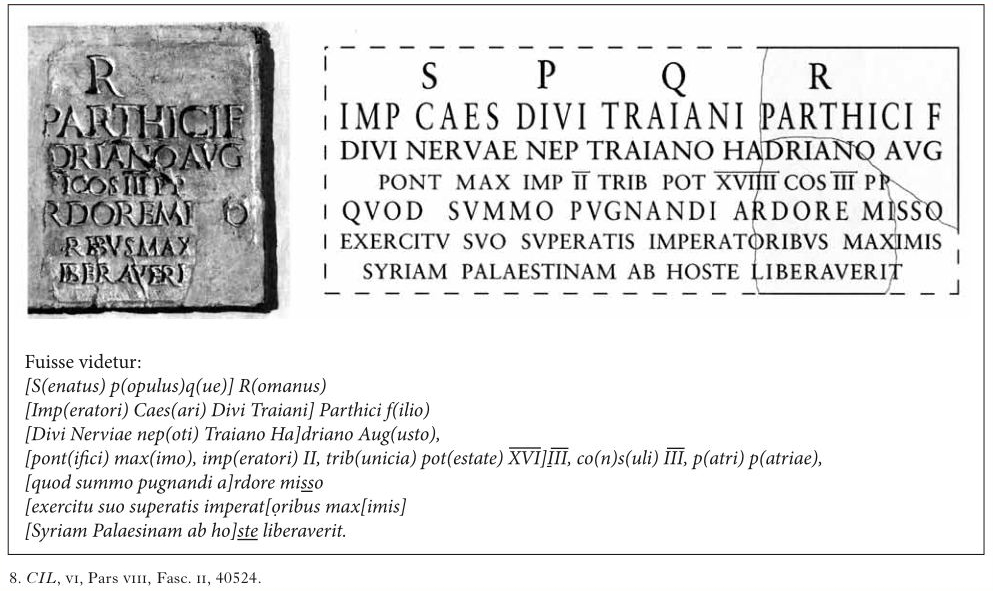

Heijnen ("Living up to expectations. Hadrian's military representation in freestanding sculpture", 2020, 200-204) refers to Hadrian's cuirassed portrait-statue from Hierapydna (and to its replicas; cf. here Fig. 29) as to the "eastern breastplate type".

Heijnen (2020) describes the iconography of Hadrian's cuirass (cf. here Fig. 29), especially the central figure of an "Athena/Palladion/Virtus", as he refers to it, who, standing on the lupa romana, is crowned by two winged Victories, and calls this iconography "trophy-type".

Contrary to all previous scholars, who have studied the iconography of Hadrian's cuirass of his portrait-statue from Hierapydna (here Fig. 29; and of its replicas) so far, Heijnen is able to demonstrate that these specific "trophy-types" are very similar of representations on cuirasses, that had been created for the Flavian emperors to honour them for their victories in the Great Jewish War (AD 66-73 n. Chr.), and in Germania. At the end of his discussion of Hadrian's "eastern breastplate type" (here Fig. 29), Heijnen (2020, 204) comes to the following, in my opinion very convincing, conclusion:

"The choice to use the `trophy-type´ [on the cuirasses of this series of portraits of Hadrian; cf. here Fig. 29] as an anchor might have been influenced by the fact that this type has been used before to commemorate the conquest of Judaea under the Flavians [my emphasis]".

In addition to this, Karanastasi, when writing her article (2012/2013), could not as yet consider the results of Lorenzo Cigaina's research (2020), whom I myself have followed above, in volume 3-1. My thanks are due to Peter Herz, who had alerted me to Lorenzo Cigaina's research on Crete.

In the following, I will, therefore, repeat some text-passages from supra, volume 3-1, where I have summarized Cigaina's research (2020) on Hadrian's cuirassed portraits in Crete, inter alia his portrait from Hierapydna (here Fig. 29). Cf. supra, in volume 3-1, p. 929:

``The observations concerning Hadrian's portrait-statue from Hierapydna by Lorenzo Cigaina (2020)

Lorenzo Cigaina (Creta nel Mediterraneo greco-romano: identità regionale e istituzioni federali, 2020, 122-124) discusses the well-known, but at the same time remarkable fact that in Crete were found five (or six?) copies of `Hadrian's portrait series´, to which the statue from Hierapydna (here Fig. 29) belongs.

Cigaina is first to connect this fact with Hadrian's improvement of a major road that connected the western part of Crete with its eastern part. We know three Hadrianic milestones of this road, which, as Cigaina (2020, 219) is able to demonstrate, are datable between AD 133-136. He, therefore, convincingly suggests that Hadrian used this road to guarantee the transportation of soldiers and supplies that he needed for his suppression of the Bar Kokhba Revolt in Judaea´´.

See also above, in volume 3-1, pp. 933-934:

``Cigaina (2020, 221-222, § IV.6) discusses Hadrian's road in Crete, known through those milestones, its possible connection with the Bar Kokhba Revolt and with Hadrian's statues of his `tipo Hierapytna´ (cf. here Fig. 29); the fact that, in his opinion, the replicas of this statue-type are datable to AD 132-138; and that the replicas, found in Crete, therefore, commemorated Hadrian's suppression of the Bar Kokhba Revolt:

"... [page 934] L'unica guerra impegnativa durante il suo [i.e., Hadrian's] regno è rappresentata dalla repressione della rivolta di Bar Kochba ed è verosimile che proprio a questo evento militare facciano riferimento le statue cretesi con corazza del `tipo Hierapytna´ [my emphasis]"´´.

That the representations on the reverses of Hadrian's coins (here Figs. 129, above; Fig. 129, below, left; Fig. 129, below, right), and consequently the portrait-statue of Hadrian from Hierapydna (here Fig. 29), which shows the emperor with an elaborate laurel crown, celebrate a military victory, is, in addition to this laurel crown, proven by the following facts: represented standing, wearing a cuirass and armed with a spear and a parazonium, Hadrian is shown in the already mentioned `archaic oriental victor pose´.

See also Karanastasi (2012/2013, 329): "An den Statuen aus Olympia und Hierapytna (8 Taf. 4, 3. 4; 12 Taf. 6, 3 - 5 [= cf. here Fig. 29]) ist der Kaiser [i.e., Hadrian] mit einem doppelreihigen Lorbeerkranz und Medaillon über der Stirnmitte porträtiert und dadurch als siegreicher Imperator gekennzeichnet [with n. 40]; my emphasis". In her note 40, Karanastasi writes: "... Zum Lorbeerkranz s.[iehe] zuletzt Bergmann 2010b [= here B. BERGMANN 2010a], 51-58".

Sam Heijnen's analysis (2020) of the iconography of the representations on Hadrian's cuirass (here Fig. 29) sounds like a repetition of the content of an honorary inscription (CIL VI 974 = 40524; here Fig. 29.1), dedicated to Hadrian in AD 134-136 by the Senate and the Roman People to commemorate his suppression of the Bar Kokhba Revolt. Cf. supra, in volume 3-1, pp. 927, 928, 929, 945, 943.

The honorary statue, to which the fragmentary inscription (CIL VI 974 = 40524; here Fig. 29.1) once belonged, had been dedicated to Hadrian between AD 134-136 by the Senate and the Roman People in honour of his suppression of the Bar Kokhba Revolt (AD 132-135 or 136).

Not by chance, this honorary statue for Hadrian had been erected within the Temple of Divus Vespasianus at the Forum Romanum in Rome, or else immediately in front of this temple (cf. here Fig. 58, labels: FORUM ROMANUM; TEMPLUM: DIVUS VESPASIANUS). Because in the pertaining inscription (here Fig. 29.1), Hadrian's victories, for which he had been honoured with this statue, are expressis verbis compared with the victories of the `imperatores maximi´ (meaning Vespasian's and Titus's victories in the Great Jewish War, AD 66-73; cf. supra, in volume 3-1, pp. 30, 738, 770, 921, 922, 924, 935, 940-941, 943), that had been fought by Vespasian and Titus in the same area of the Imperium Romanum. Note that in this inscription (here Fig. 29.1), it is stressed that Hadrian, with his victories, had even surpassed those of Vespasian und Titus (!).

With my suggestion that the honorary statue for Hadrian, to which the fragmentary inscription (CIL VI 974 = 40524; cf. here Fig. 29.1) once belonged, was erected within the Temple of Divus Vespasianus, I have followed Geza Alföldy (at: CIL VI 40524, who suggested that this honorary statue of Hadrian stood in the cella of the Temple of Divus Vespasianus), and Michaela Fuchs (2014, 130); cf. supra, in volume 3-1, p. 738.

On 31st October 2014, John Pollini was kind enough to write me by E-mail the following comment on this statement, and on 4th November 2024, John has written me the permission to publish his comment here:

"The statue set up in the Temple of Divus Vespasianus, would not have been placed within the cella but in the porch of the temple, because Hadrian was not deified. This is a tradition going back to the Pantheon, when Agrippa wanted to place a statue of Augustus in the cella, but Augustus forbade this. Under Tiberius, he did not permit a statue of himself to be set up in one of the temples in Spain, he only allowed it to be an ornamentum - undoubtedly, therefore, in the porch. That was the function of the statues of Agrippa and Augustus in the porch of the Pantheon. There are other examples [my emphasis]".

Already Annalina Calò Levi (1948, 30-33, 35, 37-38) and Cornelius Vermeule (1981, 25) had realized that on the reverses of the coins, issued by Hadrian in Rome (here Fig. 129, above; Fig, 129, below, left; Fig. 129, below, right), appears a cuirassed portrait-statue of Hadrian that follows exactly the same iconography as Hadrian's portrait-statue from Hierapydna (here Fig. 29).

As mentioned above, Annalina Calò Levi (1948, 30-31, 38 with n. 36) had added to this the suggestion that - after AD 134 - this statue of Hadrian, which is represented on the reverses of those coins (here Fig. 129, above; Fig, 129, below, left; Fig. 129, below, right), had been dedicated in Rome; she obviously assumed this, because Hadrian had minted those coins in Rome.

And we have also seen above that Vermeule (1981, 25; quoted verbatim supra, in volume 3-1, p. 918) had been first to suggest that the portrait-statue of Hadrian from Hierapydna had been dedicated in order to honour the emperor for his suppression of the Bar Kokhba Revolt, arguing inter alia with the fact that this statue shows Hadrian with a "mature portrait" (cf. here Fig. 29).

Interestingly, Claudio Parisi Presicce (2000), who knew only altogether 15 copies of this statue-type of Hadrian from Hierapydna (here Fig. 29), had already observed the strange fact that those statues had been created in great haste - as he himself interpreted the fact that most of those statues, which he knew, seemed to be unfinished.

In the case of the statue from Hierapydna (here Fig. 29), the face has not received its final finish, and both of its ears are still only roughened out; compare for those facts also the observations by Birgit Bergmann (2010b, 210-211, Abb. 2a.c-d); and Pavlina Karanastasi (2012/ 2013, 334 with n. 57, p. 335).

But I have a problem with this hypothesis: why was, according to this scenario, the head of this portrait-statue of Hadrian sculpted last? In theory, an artist, specializing in portraits, could, of course, have done this job only after the rest of the sculpture had already been finished by another sculptor - especially, provided of this portrait of Hadrian had been created a whole series of copies.

My thanks are, therefore, due to Hans Rupprecht Goette for telling me by E-mail on 7th November 2024 that he is in the course of studying the following questions: whether the portrait-statue of Hadrian from Hierapydna (here Fig. 29) was renewed as part of a repair, and, if that should have been the case, why and when this could have happened. To this I will come back below (cf. infra, in Post Scriptum, at point 4.)).

Parisi Presicce (2000, 29) writes: "L'esecuzione, benché attribuita a una o più officine greche, è nella maggior parte dei casi rapida, poco raffinata ed è il frutto evidente dell'esigenza di rispondere in tempi brevi alla forte domanda delle città e dei magistrati desiderosi di mostrare la loro adulazione per l'imperatore, forse subito dopo la sua divinizzazione [my emphasis]".

Concerning the represented age of Hadrian in his portrait-statue from Hierapydna, I agree with Vermeule (1981, 25).

First of all because of Hadrian's coins (here Fig. 129, above; Fig. 129, below, left; Fig. 129, below, right), on which, in my opinion, on the reverses the prototype of the statue from Hierapydna (Fig. 29) appears, and on the obverses portraits of the clearly elderly Hadrian. All those coins are dated in the catalogues of the British Museum to AD 130-138, and by Peter Franz Mittag (2010, 48): "vor 132(?)-138(?) n. Chr.". As we shall see below (in Post Scriptum, at point 3.)), I myself date those coins of Hadrian to: `AD 136´.

See also the photos of Hadrian's head of his portrait-statue from Hierapydna, published by Karanastasi (2012/2013, 387, Taf. 6,3-5 [= here Fig. 29]), and compare those with Hadrian's portrait on an aureus, which is one of the earliest coins, issued by the Emperor Hadrian in AD 117 in Rome (here Fig. 142). As mentioned above, according to Karanastasi (2012/2013, 381), the portrait-statue of Hadrian from Hierapydna (here Fig. 29, and its replicas) were commissioned `shortly after AD 117´.

For a discussion of the coin (here Fig. 142); cf. <https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Konstantin_Hadrian_Koloss_09.html>.

Because of all that information, which has been summarized above, I myself have suggested that Hadrian's cuirassed statue from Hierapydna (here Fig. 29, and its replicas), are copies of that honorary statue of Hadrian, which the Senate and the Roman People had erected within the Temple of Divus Vespasianus at the Forum Romanum in Rome, or immediately in front of this temple (cf. here Fig. 58, labels: FORUM ROMANUM; TEMPLUM: DIVUS VESPASIANUS), and to which the fragmentary inscription (CIL VI 974 = 40524; here Fig. 29.1) had once belonged;

cf. supra, in volume 3-1, p. 724 ff., at A Study on the colossal portrait of Hadrian (now Constantine the Great) in the courtyard of the Palazzo dei Conservatori at Rome (cf. here Fig. 11); p. 728 ff., at Part I. The statue of Hadrian (now Constantine the Great) in the courtyard of the Palazzo dei Conservatori (cf. here Fig. 11), the inscription (CIL VI 974 = 40524; cf. here Fig. 29.1), and the cult-statue of Divus Vespasianus. With The Contribution by Hans Rupprecht Goette on the reworking of the portrait of Hadrian (now Constantine the Great); and p. 899 ff., at A Study on Hadrian's portrait-statue from Hierapydna (cf. here Fig. 29).

To this we may now add a fact that was not as yet addressed by the above-mentioned scholars, who have so far studied Hadrian's coins (here Fig. 129, above; Fig. 129, below, left; Fig. 129, below, right): on the obverses of those coins appear the laureate portraits of Hadrian. My thanks are due to Franz Xaver Schütz for discussing this point with me.

Compare the iconography of the IVDAEA CAPTA-coins of Vespasian and Titus (here Figs. 130; 131a, 131b; 131c), that is in this detail identical, showing on the obverses the laureate portraits of Vespasian and of Titus. Add to this the iconography that was chosen for the reverses of those coins, issued by Hadrian: it is almost identical with the representations of Vespasian and Titus, who likewise appear in an `archaic oriental victor pose´ on the reverses of their IVDAEA CAPTA-coins (here Figs. 130; 131a; 131b).

That the iconography on the reverses of Hadrian's coins (here Fig. 129, above; 129, below, left; 129, below, right) had been copied after Vespasian's IVDAEA CAPTA-sestertii (here Fig. 130) had first been observed by Cornelius Vermeule (1981, 24-25; quoted verbatim supra, in volume 3-1, p. 918).

For the IVDAEA CAPTA-sestertii, issued by Vespasian and Titus (here Figs. 130; 131a; 131b; 131c); cf. <https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Hadrian_Ehrenstatue_in_Rom.html>.

Considering those remarkable parallels of the iconography of Hadrian's coins (here Fig. 129, above; 129, below, left; 129, below, right) with Vespasian's and Titus's IVDAEA CAPTA-sestertii (here Figs. 130; 131a; 131b; 131c) we should ask, why and when Hadrian could have made such a proud statement about any of his own achievements.

I believe the fact that Hadrian, by ordering that on his coins (here Fig. 129, above; Fig. 129, below, left; Fig. 129, below, right) should be copied those iconographic details of Vespasian's and Titus's IVDAEA CAPTA-coins (here Figs. 130; 131a; 131b; 131c) - especially that his portraits on the obverses of his coins should likewise be represented laureate - may be explained with the following results of the suppression of the Bar Kokhba Revolt that have been commented upon by Evan Haley (2005).

Evan Haley (2005, 976, n. 29) writes:

"[Hadrian's] conferment of the ornamenta triumphalia on Sex. Iulius Severus, Publicius Marcellus, and Haterius Nepos, in addition to the insertion of `Imperator II´ in Hadrian's titulature [my emphasis]";

cf. Evan Haley (2005, 976, n. 29), quoting for all that: "See now W. Eck, The Bar Kokhba Revolt : The Roman Point of View in JRS 89, 1999 [= here W. ECK 1999d], p. 76-89, esp. 82-87".

As we shall see below (in Post Scriptum, at point 3.)), my just-formulated assumption that Hadrian may have ordered to be represented laureate on the obverses of his coins (here Fig. 129, above; Fig. 129, below, left; Fig. 129, below, right), because he had accepted in AD 136 his second imperatorial acclamation, is actually based on facts.

See also W. Eck ("Kaiserliche Imperatorenakklamation und ornamenta triumphalia", 1999c). I thank Peter Herz for sending me this publication, discussed in his third Contribution to this book: Der Übergang von Trajan auf Hadrian und das erste Regierungsjahr Hadrians (cf. supra, in volume 3-1, pp. 68, 1274-1283).

Werner Eck (1999c, 225) writes:

"Die letzten ornamenta triumphalia wurden unter Hadrian vergeben ... Seit langem bekannt waren die ornamenta für Sex. Iulius Severus, der sie nach der Niederzwingung des Bar Kochba-Aufstandes erhielt. [With n. 21]. Hadrian hatte aus diesem Anlaß zum einzigen Mal während seiner Regierungszeit eine Akklamation als imperator akzeptiert. Seit Anfang 136 führte er in seiner Titulatur die Bezeichnung imperator II [my emphasis]".

Cf. Dietmar Kienast, Werner Eck and Matthäus Heil (2017, 123): "Hadrian (11. Aug.[ust] 117-10. Juli 138) ...

Anfang 136 Annahme der Akklamation als imp.[erator] II".

Cf. Werner Eck (1999c, 227):

"Somit dürfte erwiesen sein, daß seit augusteischer Zeit und gerade wegen des augusteischen Beispiels Triumphalinsignien dann vergeben wurden, wenn der Herrscher wegen eines Sieges seine eigene Akklamation als imperator zugelassen und damit kundgetan hatte, daß der Sieg mit einem Triumph gefeiert werden könnte ... Der eigentlich siegreiche senatorische Feldherr konnte immer dann die Abzeichen des Triumphes erhalten, wenn der Kaiser durch einen Triumph oder durch eine Akklamation den Sieg als triumphwürdig anerkannt hatte. [With n. 33, with further discussion; my emphasis]".

In his note 21, Eck writes: "CIL III 2830+9891 = D. 1056; AE 1904,9".

Cf. E. Haley, "Hadrian as Romulus or the Self-Representation of a Roman Emperor", Latomus 64 (2005) 969-980. I thank Franz Xaver Schütz for providing me with this publication.

That the reverses of Hadrian's coins (here Fig, 129, above; Fig. 129, below, left; Fig. 129, below, right) commemorate a military victory of the emperor, is, in addition, indicated by still another iconographic detail, the meaning of which has so far not been discussed here (to this I will come back below).

On 15th October 2024, Lorenzo Cigaina, whom I had likewise sent the Link to the Preview of FORTVNA PAPERS volume III-2 on the "Ehrenstatue Hadrians in Rom für die Niederschlagung des Bar Kochba-Aufstandes", was kind enough to alert me to Karanastasi's most recent publication (2024) on Hadrian's portrait-statue from Hierapydna (here Fig. 29).

Cf. P. Karanastasi, "Political upheavals and the Roman army: looking for traces of the Roman army in Crete", in: J.E. Francis and M.J. Curtis (eds.), Contextualizing Imperial Disruption and Upheavals and their Associated Research Challenges (= Cretan Studies: New Approaches and Perspectives in the Study of Hellenistic, Roman and Early Byzantine Crete, Volume 1), Oxford and Philadelphia: Oxbow Books, 2024, pp. 43-56.

Pavlina Karanastasi (2024, 50) writes:

"Finally, the numerous statues of Hadrian on the island [i.e., Crete] exclusively in the cuirass type and especially in the so-called eastern or Hierapytna type [cf. here Fig. 29] with a captive barbarian at the Emperor's feet, must, as I have already pointed out, be probably related to the role that Crete was called upon to play in the events of AD 116/117 (Karanastasi 2012-2013).

In the case of the statue of Hadrian from Hierapytna (Fig. 5.12 and 5.13; Bergmann 2010 [= here B. BERGMANN 2010b], 206-20; Figs. 1-4; Karanastasi 2012-2013, 362-63, pl. 6), with his foot on the back of a prostrate female personification, commonly identified with Parthia, a composite bow strapped to a quiver is shown on the support of the statue. This weapon, has been associated with the enemy Parthia (Bergmann 2010 [= here B. BERGMANN 2010b], 247-48), but should rather be seen as referencing Crete, its archers and their contribution to suppressing the revolt of the Jews (Karanastasi 2012-2013, 348; Cigaina 2016, 324, with n. 70) [my emphasis]".

Cf. L. Cigaina, "Der Kaiserkult bei den Kretern in Bezug auf ihre Teilhabe am Militärwesen des römischen Reiches", in A. Kolb and M. VitaIe (eds.), Kaiserkult in den Provinzen des Römischen Reiches: Organisation, Kommunikation und Repräsentation (Akten der Tagung, Zürich, 25.-27. September 2014), Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, 2016, pp. 309-936.

As Karanastasi (2024, 50) herself in the just-quoted passage of her text states, she has repeated in this publication several of her assumptions already published in her article of 2012/2013.

Interestingly, Karanastasi (2024, 50) quotes from the article of Lorenzo Cigaina (2016), but although she also quotes Cigaina's book (2020) in her bibliography, she does not discuss the fact that Cigaina (2020, 221-222, § IV.6, quoted verbatim supra) dates the portrait of Hadrian from Hierapydna (here Fig. 29) and all the 5 (or six?) replicas of this statue, found in Crete, differently than she herself does, namely to `AD 132-138´.

Nor does Karanastasi (2024, 50) mention the fact that Cigaina (2020) also explains the dedication of those portrait-statues of Hadrian in Crete (cf. here Fig. 29, and its replicas) differently than she herself does, namely with Hadrian's suppression of the Bar Kokhba Revolt (AD 132-135 or 136).

And exactly as in her earlier publication, Karanastasi (2024, 50) does not mention the fact that Cornelius Vermeule (1981, 25, quoted verbatim supra, in volume 3-1, p. 918) had interpreted the vanquished figure, on which Hadrian (here Fig. 29) sets his left foot, as a "Jewish boy".

My thanks are due to John Pollini, who wrote me by E-mail on 31st October 2024 the following comment on this statement; on 4th November 2024, he has written me the permission to publish his comment here:

"And clearly the downtrodden figure under Hadrian's foot was not a Jew but a Jewess, personifying Judea, as her female hairdo makes clear".

As I should only realize later, Birgit Bergmann (2010b, 209-210 with n. 10, Abb. 3a-c) is able to show that the head of this barbarian figure does not belong; cf. Pavlina Karanastasi (2012/2013, 362, at cat. no. 12).

Concerning this figure, on which Hadrian (here Fig. 29) sets his left foot, Cigaina (2020), has added an observation, made by Birgit Bergmann (2010b, 254-258). Cigaina (2020, 222, n. 599; the relevant passage is quoted in more detail supra, in volume 3-1, on pp. 933-935) writes:

"Sulla figura secondaria del barbaro sottomesso (inginocchiato o steso a terra) che accompagna tutte le statue cretesi eccetto quella di Cnosso, vd. [vedi] Bergmann 2010 [= here B. BERGMANN 2010b], 242-248 ... Il barbaro di Hierapytna [cf. here Fig. 29] è stato identificato come Parto ... Sulla probabile allusione dei barbari orientali alla rivolta di Bar Kochba, vd. [vedi] Bergmann 2010 [= here B. BERGMANN 2010b], 254-258: l’evento fu percepito come una seria minaccia per la sicurezza dell’Impero anche a causa di una possibile offensiva partica nell’Oriente divenuto instabile [my emphasis]".

What then is the above-mentioned iconographic detail, the meaning of which has so far not been addressed here, that proves as well that the reverses of those coins, issued by Hadrian (here Fig. 129, above; Fig. 129, below, left; Fig. 129, below, right), commemorate a military victory of the emperor ?

It is Hadrian's spear (hasta), pointed down !

My thanks are due to John Pollini, with whom I could discuss this matter in an E-mail correspondence from 17th-22nd October 2024. I had asked John for advice, after having found his relevant remark in his book (From Republic to Empire: Rhetoric, Religion, and Power in the Visual Culture of Ancient Rome 2012, 190).

In his discussion of the bronze statue of Germanicus at Amelia, kept in the Archaeological Museum there (his plate XIV, with n. 130, providing references), John Pollini (2012, 190) writes:

"Germanicus' bronze spear is held with its point facing down ...The spear pointed down is also found on a denarius of Vespasian (fig. IV.25) showing him wearing a cuirass ... [with n. 131]. For the Romans, the inversion of the spear point in this manner signified peace. A late Republican-early Augustan painting shows Aeneas' son Iulus and the Etruscan king Mezentius making a peace treaty, with their two spears planted point-down in the ground as a symbol of making peace [with n. 132; my emphasis]".

In his note 131, Pollini writes: "BMCRE II,8 (no. 47), pl. 1.15; Kent (1978) 288 (no. 225), pl. 64 ...".

Cf. J.P.C. Kent, Roman Coins (New York: Abrams 1978).

In his note 132, Pollini writes: "La Regina (1998) 54 with color photo (two figures on the far left)".

Cf. A. La Regina (ed.) 1998, Museo Nazionale Romano, Palazzo Massimo alle Terme (Milano: Electa 1998).

The caption of Pollini's "fig. IV.25" reads: "Fig. IV.25. Denarius (rev.[erse]: cuirassed Vespasian holding spear point down), 69-70 C.E. After Kent (1978) pl. 64.288".

John Pollini answered my question by E-mail of 19th October 2024, and on 22nd October, he has kindly allowed me to quote here the relevant passage from this E-mail:

"The spear pointed down is not just a symbol of peace, but of peace through victory. That is the whole point of the spear point-down ... no pun intended. See also, Mezentius and Ascanius making a peace treaty in the painted wall frescoes from the Family tomb of Statilius Taurus on the Esquiline Hill. Their spears are stuck point-down in the ground. See also the Germanicus statue from Amelia with his spear pointed down. There is also coin evidence of Vespasian, with spear pointed down, as well as a coin of Antoninus Pius showing Mars Ultor holding his spear pointed down. It is based on simple logic !".

In addition to this, John Pollini was kind enough to send me his article on this bronze statue of Germanicus in Amelia, in which he adds further information concerning the meaning of this spear.

Cf. John Pollini, "The Bronze Statue of Germanicus from Ameria (Amelia)", AJA 121, Number 3, July 2017, pp. 425–437.

Pollini (2017, 428) writes: "In his left arm, the Amelia Germanicus cradles a spear (hasta), symbolic of his legal military command (imperium). The point of the spear is turned downward to signify peace through victory (see figs. 2, 4a), as in the case of a coin image of the emperor Vespasian carrying a spear with the point down and the butt end (sauroter) turned up. [With n. 18; my emphasis]".

In his note 18, Pollini writes: "For the significance of the downward-pointed spear with reference to the image of Vespasian on the coin, the bronze statue of Germanicus, and the statue of Augustus from Prima Porta, see Pollini 2012, 190, fig. 4.25 ... [quoted in part verbatim supra]".

Interestingly, Pollini (2017, 428) calls Germanicus' `spear´ a "hasta", a Latin term that in German is usually not translated as `Speer´ (as in English), but instead as `Lanze´. My thanks are due to Peter Herz for discussing this point with me in a telephone conversation on 23rd October 2014.

To this, Pollini (2017, 428) adds, that this "spear (hasta) [is] symbolic of his [i.e., Germanicus'] legal military command (imperium)".

Let's now apply John Pollini's (2017, 428) findings concerning a spear with its point turned downwards to Hadrian's coins, discussed here (Fig. 129, above; Fig. 129, below, left; Fig. 129, below, right):

Hadrian, holding this spear (hasta) means:

a) that he had in the war, to which this coin-image refers, "the legal military command (imperium)", as Pollini (2017, 428) writes; and because -

b) the point of Hadrian's spear is turned downwards, this means that the emperor has ended the relevant war victoriously, or in other words, that Hadrian has established `peace through victory´ in the area in question, as John Pollini (2017, 428) writes.

We have already heard that the iconography, chosen for the reverses of Hadrian's coins (here Fig. 129, above; Fig. 129, below, left; Fig. 129, below, right), appears also on the coins of other emperors:

"Lorenzo Cigaina (2020, 267, Anm. 801) stellt fest, dass die für Hadrian auf dem Sesterz (hier Fig. 129, above) gewählte Darstellung auch auf Münzen anderer römischer Kaiser, wie z.B. Caracalla, wiederkehrt, und kommt zu folgender Bewertung dieser Ikonographie: ``L’imperatore è sempre in abito militare e armato. Il tipo viene interpretato perlopiù in riferimento alla repressione di disordini ... [my emphasis]´´"; cf. <https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Hadrian_Ehrenstatue_in_Rom.html>.

I, therefore, suggest that, on the reverses of Hadrian's coins (here Fig. 129, above; Fig. 129, below, left; Fig. 129, below, right), by means of the crocodile, which is similarly represented as in the iconography `Horus killing the crocodile´ (cf. here Fig. 129.1), and by means of Hadrian's downwards pointed spear, `we are told the whole story´.

Hadrian's stepping with his left foot on this crocodile, defines the great problem, the emperor had to face: the Bar Kokhba Revolt (AD 132-135 or 136) in the Roman province of Judaea; whereas Hadrian, holding with his right hand his spear with its point turned downwards, shows the fortunate outcome: the emperor has ended this war victoriously, re-establishing peace in this province.

Whereas on all of Hadrian's coins, illustrated here (Fig. 129, above; Fig. 129, below, left; Fig. 129, below, right) the downwards held point of his spear is clearly visible, this is not the case (probably not any more: as we shall see below, this is actually true) on Vespasian's and Titus' IVDAEA CAPTA-sestertii, shown here on Figs. 130; 131a; 131b.

But because the reverses of Hadrian's coins were copied after the reverses of Vespasian's sestertii (cf. here Fig. 130), as already Cornelius Vermeule had observed (1981, 25, quoted verbatim supra, in volume 3-1, p. 918) - see also the identical iconography on the reverse of Titus' IVDAEA CAPTA-sestertius (here Fig. 131a), and the likewise identical iconography on the IVDAEA CAPTA-sestertius, issued by Vespasian, but representing Titus (here Fig. 131b) - we can now conclude with confidence the following (we shall see below that this is actually the case):

that points a) and b) had originally also been true for those IVDAEA CAPTA-coins of Vespasian and Titus (here Figs. 130; 131a; 131b): by means of their spears, also Vespasian and Titus were thus characterized on the reverses of their coins as those, who, in the represented war, had "the legal military command (imperium)" (cf. J. POLLINI 2017, 428), and - most importantly - because Vespasian and Titus hold on those coins their spears with their points facing down: they too had ended the relevant war victoriously, and had both established `peace through victory´ in the Roman province of Judaea (cf. J. POLLINI 2017, 428).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My above-made assumption that Vespasian, on his IVDAEA CAPTA- sestertius (here Fig. 130), originally held his spear with its visible point turned downwards, is indeed true. John Pollini was kind enough to send me on 31st October 2024 a jpeg-file and the Link to a copy of this coin, which is owned by the American Numismatic Society: "RIC II, Part 1 (second edition) Vespasian 167), BMC 543".

I also thank Franz Xaver Schütz, who, on the same day, found out in a special research on the Internet, that this is the only known copy of this coin, on which the point of Vespasian's spear, which is turned downwards, is actually visible, and that very well (!);

cf. <https://numismatics.org/collection/1944.100.39981> ; and here Fig. 130 .

My thanks are also due to the following colleagues and friends, whom I sent in October-November 2024 the Link to the Preview of the "Ehrenstatue Hadrians in Rom für die Niederschlagung des Bar Kochba-Aufstandes", as well as this text, for writing me their corrections and comments: to Hans Rupprecht Goette; to Lorenzo Cigaina, who was also kind enough to alert me to the article by Pavlina Karanastasi (2024); to Eberhard Thomas, to Peter Herz; to Eric M. Moormann; and to John Pollini.

POST SCRIPTUM

To the above-discussed subjects I wish to add some more information, which I only found out after having finished writing this text (as I erroneously believed !) on 4th November 2024.

1.) concerning the meaning of Hadrian's spear (hasta), with its point turned downwards, which is visible on the coins (here Fig. 129, above; Fig. 129, below, left; Fig. 129, below, right).

When writing my relevant text-passage, I had overlooked that already Birgit Bergmann (2010b) knew the meaning of this gesture. Bergmann's observations were quoted by Pavlina Karanastasi (2012/2013), whose account I happened to find first (on 4th November 2024); in the following, I will quote both.

Karanastasi (2012/2013, 323-324) writes:

"Der ideologische Abstand dieser Bildnisstatue [of the portrait-statue of Hadrian from Hierapydna; here Fig. 29] zu der etwa 140 Jahre früher entstandenen Panzerstatue des Augustus von Prima Porta ist trotz des ebenso reichen Bildschmucks unverkennbar [with n. 3, providing references for this statue of Augustus]. Während die Augustusfigur das Grundschema und die kontrapostisch ruhige Bewegung klassischer Werke wie des Doryphoros des Polyklet widerspiegelt und sich mit in die [page 324] Ferne gerichtetem Blick deutlich vom Betrachter absetzt, schaut Hadrian ihm düster und direkt in die Augen und macht so seine Entschiedenheit, den erniedrigten Gegner zu vernichten, mehr als deutlich. Die einst vorhandene, mit der seitlich erhobenen Rechten in den Boden gestemmte Lanze wird die Absicht des Imperators zusätzlich unterstrichen haben (vgl. [vergleiche] Abb. 7) [with n. 4; my emphasis]".

In her note 4, Karanastasi writes: "Zum Münzbild [i.e., her Abb. 7 = here Fig. 129, below, right] s. u. [siehe unten] mit Anm. 191 [which is quoted verbatim supra]. Zur verkehrt herum in den Boden gestemmten Lanze und ihrer Bedeutung für den Dargestellten [i.e., Hadrian] als Befrieder der Welt s. [siehe] Bergmann 2010a [= here B. BERGMANN 2010b], 257 mit Anm. 137 ... [my emphasis]".

Birgit Bergmann (2010b, 256-257, in her Section: "Bar Kochba") writes: