von

Chrystina Häuber

Der folgende Text enthält Literaturangaben und viele Abbildungsnummern. Vergleiche FORTVNA PAPERS vol. III-1, S. 1097 ff. für die entsprechenden Bildunterschriften ("List of illustrations"), S. 1128, für die Abkürzungen ("Abbreviations") , und S. 1129 ff., für die Literatur ("Bibliography") .

Im folgenden Text wird häufig auf Passagen in FORTVNA PAPERS vol. III-1 hingewiesen; cf. https://FORTVNA-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3.html

Dieser

Text, eine Preview meines Buches über Domitian in FORTVNA PAPERS vol. III-2,

ist ein Ergebnis der Preview mit folgendem Titel:

Chrystina Häuber, Die neuesten

Forschungsmeinungen zu folgenden Themen in 9 Kapiteln:

Hadrian / Konstantin in Rom

- die Kolossalstatue in Rom, die in ein

Bildnis Konstantins des Großen umgearbeitet worden ist

- die Fragmente der Kolossalstatue Konstantins

des Großen im Konservatorenpalast in Rom -

- umgearbeitet aus Domitians Kultbild des

Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus?

- oder umgearbeitet aus dem Kultbild des Divus Hadrianus im Hadrianeum in Rom?

- die im Maßstab 1:1 rekonstruierte

Kolossalstatue Konstantins des Großen in den Musei Capitolini, im Giardino der

Villa Caffarelli

cf.

<https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Konstantin_Hadrian_Koloss_01.html>:

Further research on those subjects has led to

results, which are presented in the following text, written in English and

divided into three Chapters. In this text are quoted many passages from the

Preview "Hadrian / Konstantin in Rom", which was published in German.

For this new text, those passages were translated into English.

Let's begin with the German titles of these

three Chapters, followed by English translations of them:

I.) Das kolossale Konstantinportrait (hier Figs. 11; 11.1; 156) kann nicht, wie Claudio Parisi Presicce (2022)

vorgeschlagen hat, aus Domitians (viertem) Kultbild des Iuppiter Optimus

Maximus Capitolinus umgearbeitet worden sein. Dieses Jupiterkultbild war

nämlich, wie Birgit Bergmann (2010a) feststellt, mit einem Eichenkranz bekränzt

(vergleiche hier Figs. 13; 158),

eine Tatsache, die mir zuvor unbekannt gewesen ist. Das Konstantinportrait

(hier Fig. 11) hat aber mit

Sicherheit nie einen Kranz getragen.

Dieser

Text enthält außerdem Zusammenfassungen von Themen, die in der Preview "Hadrian / Konstantin in Rom" in

folgenden Kapiteln behandelt werden; vergleiche Kapitel 1: Die Motivation,

diesen Text zu verfassen: Claudio Parisi Presicces (2022) Rekonstruktion des

Konstantinkolosses (hier Fig. 156);

Kapitel 2, Punkt 1.): Cécile Evers' Beweis, dass der Kopf des Konstantinkolosses

(hier Fig. 11) aus einem Portrait

des Hadrian umgearbeitet worden ist; Kapitel 2, Punkt 1.)-Kapitel 7: Parisi

Presicces (2005; 2006a; 2006b; 2022) Beobachtungen zu Domitians (viertem)

Kultbild des Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus; Kapitel 2, Punkt 2.):

Die vier Tempel des Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus und ihre vier

Kultbilder; Kapitel 3: Die Kopien von Domitians (viertem) Kultbild des Iuppiter

Optimus Maximus Capitolinus; Kapitel 5-Kapitel 6: Parisi Presicces (2006b;

2022) Beobachtungen zur Konstantinstatue in Rom, die Eusebius (Hist. Eccl. 9,9,10-11) beschrieben hat;

Kapitel 6-Kapitel 7: Parisi Presicces (2022) Vorschlag, dass der Koloss des

Konstantin (hier Figs. 11; 11.1; 156)

aus Domitians (viertem) Kultbild des Jupiter Capitolinus umgearbeitet worden

sei, und meine Widerlegung dieser Hypothese; Kapitel 9: Meine eigene Hypothese,

dass der Koloss des Konstantin möglicherweise aus dem Kultbild des Divus Hadrianus im Hadrianeum umgearbeitet worden sei.

I.) Claudio Parisi Presicce's hypothesis (2022), according to which

the colossal portrait of Constantine (here Figs.

11; 11.1; 156) has been reworked from Domitian's (fourth) cult-statue of

Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus, cannot possibly be true, and that for the

following reasons. As observed by Birgit Bergmann (2010a), this cult-statue of

Jupiter (cf. here Figs. 13; 158) was

crowned with an oak wreath, a fact that was previously unknown to me. The

portrait of Constantine (here Fig. 11),

on the other hand, has certainly never worn a wreath.

In

addition, this text contains summaries of subjects, that are discussed in the

following Chapters of the Preview "Hadrian

/ Konstantin in Rom"; cf. Kapitel 1: the motivation to write this

text: Claudio Parisi Presicce's (2022) reconstruction of the colossus of

Constantine (here Fig. 156); Kapitel

2, at point 1.): Cécile Evers's proof, that the head of the colossus of

Constantine (here Fig. 11) has been

reworked from a portrait of Hadrian; Kapitel 2, at point 1.)-Kapitel 7: Parisi

Presicce's (2005; 2006a; 2006b; 2022) observations concerning Domitian's

(fourth) cult-statue of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus; Kapitel 2, at

point 2.): the four Temples of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus

and their four cult-statues; Kapitel 3: the copies of Domitian's (fourth)

cult-statue of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus; Kapitel 5-Kapitel 6:

Parisi Presicce's (2006b; 2022) observations concerning the statue of

Constantine in Rome, which has been described by Eusebius (Hist. Eccl. 9,9,10-11); Kapitel 6-Kapitel 7: Parisi Presicce's

(2022) suggestion, that the colossus of Constantine (here Figs. 11; 11.1; 156) has been reworked from Domitian's (fourth)

cult-statue of Jupiter Capitolinus, and my rejection of this hypothesis;

Kapitel 9: my own hypothesis, that the colossus of Constantine has possibly

been reworked from the cult-statue of Divus

Hadrianus in the Hadrianeum.

II.) Claudio Parisi Presicce (2022, 389) behauptet (irrtümlich),

dass Domitians Kultbild des Jupiter Capitolinus in der erhobenen, rechten Hand

einen Globus mit darauf stehender Victoriastatuette hielt (vergleiche hier Fig. 10). Erst nachdem die Preview zum

Thema "Hadrian / Konstantin in Rom"

(am 24. September 2024) auf unserem Webserver publiziert war (siehe Kapitel 4),

hat Franz Xaver Schütz (am 7. Oktober 2024) das Exemplar von Domitians Denar

mit Darstellung seines (vierten) Tempels des Iuppiter Optimus Maximus

Capitolinus in der Bibliothèque Nationale de France gefunden, auf dem noch sehr

viel besser als auf der Münze im British Museum erkennbar ist (die uns bereits

bekannt war), dass Domitians Jupiter Capitolinus mit seiner rechten, auf dem

rechten Oberschenkel ruhenden, Hand ein Blitzbündel hielt. Wir bilden hier

deshalb jetzt beide Exemplare dieser Münze auf Fig. 83 ab.

II.) Claudio Parisi Presicce (2022, 389) asserts (erroneously) that

Domitian's cult-statue of Jupiter Capitolinus held in his right, raised hand a

globe surmounted by a standing statuette of Victory (cf. here Fig. 10). Only after the Preview "Hadrian / Konstantin in Rom" had

been published on our Webserver (on 24th September 2024; see Kapitel 4), Franz

Xaver Schütz has found (on 7th October 2024) the copy of Domitian's denarius with the representation of his

(fourth) Temple of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus, kept in the

Bibliothèque Nationale de France. On this coin it is much better visible than

on the coin in the British Museum (which we knew already before) that

Domitian's Jupiter Capitolinus held with his right hand a thunderbolt which was

lying on his right thigh. We, therefore, illustrate here on Fig. 83 both copies of this coin.

III.) Wie Cécile Evers (1991) nachgewiesen hat;

vergleiche

die Preview "Hadrian / Konstantin

in Rom", Kapitel 2, zu Punkt 1.);

cf.

<https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Konstantin_Hadrian_Koloss_02.html>,

- war

das Portrait des

Konstantinkolosses (vergleiche hier Fig.

11) aus einem Bildnis des Kaisers Hadrian umgearbeitet worden. Nota bene:

Als Evers ihren Aufsatz publizierte, ging die Forschung noch davon aus, dass

für die Konstantinstatue (hier Figs. 11;

11.1; 156) Teile von verschiedenen

kolossalen Marmorstatuen wiederverwendet worden waren.

Dank der

von ihm in Auftrag gegebenen Marmortests konnte jedoch Claudio Parisi Presicce

(2005; 2006b; 2022) inzwischen klarstellen, dass statt dessen der gesamte

Konstantinkoloss aus einer einzigen

Statue umgearbeitet worden war, die aus der besten Qualität parischen Marmors,

namens lychnites, bestand.

Da diese

originale Statue Hadrian barfuss zeigte, habe ich vorgeschlagen (s.o., in Band

3-1, S. 498-499, 726, 729, 737-738, 758), dass sie den vergöttlichten Kaiser,

den Divus Hadrianus, dargestellt

habe, wobei es sich, meiner Meinung nach, um das Kultbild des Divus Hadrianus im Hadrianeum gehandelt haben könnte.

Nachdem

diese Forschungen in der Preview "Hadrian

/ Konstantin in Rom" auf unserem Webserver publiziert waren (siehe

Kapitel 8), habe ich diesen Text einigen Kollegen und Freunden geschickt und

sie gefragt, wie sie die Barfüßigkeit dieses kolossalen Hadrianportraits deuten

würden.

Lorenzo

Cigaina schrieb mir Folgendes: "Die Barfüßigkeit könnte wohl auf den

göttlichen bzw. [beziehungsweise] vergöttlichten Status hindeuten, wie man es

bei der berühmten Prima-Porta-Statue des Augustus festgestellt hat".

Und John

Pollini antwortete auf meine diesbezüglich Frage: "In the Prima Porta

statue, Augustus also appears as a hero, one who was mortal but possessed

divinity in life (therefore of a dual nature)".

Im

Zusammenhang meiner Diskussion mit Eberhard Thomas, wie man wohl das Problem

gelöst haben könnte, das hier betrachtete Bildnis des vergöttlichten Hadrian in

ein Portrait des (noch lebenden) Kaisers Konstantin umzuwandeln, wies mich

Eberhard darauf hin, dass man diesem barfüßigen Hadrianbildnis womöglich

Sandalen angezogen hat (!). Wie ich erst daraufhin festgestellt habe, sind an

beiden Füßen des Konstantinkolosses in sehr flachem Relief die Riemen von

Sandalen eingetieft. Ich vermute deshalb als Arbeitshypothese, dass diese

Reliefdarstellungen von Sandalenriemen im Zusammenhang der Umwandlung des

originalen Hadrianportraits in ein Bildnis des Konstantin ausgeführt worden

sind, um dem Künstler, der diese Sandalen ergänzt hat, als Hilfslinien zu

dienen.

III.) As Cécile Evers (1991) was able to prove;

see the

Preview "Hadrian / Konstantin in

Rom", Kapitel 2, at point 1.);

cf.

<https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Konstantin_Hadrian_Koloss_02.html>,

- the portrait of the colossus of

Constantine (cf. here Fig. 11) had

been reworked from a portrait of the Emperor Hadrian. Nota bene: When Evers

published her article, scholars still believed that the statue of Constantine

(here Figs. 11; 11.1; 156) had been

created by re-using parts of different

colossal marble statues.

In the

meantime, Claudio Parisi Presicce (2005; 2006b; 2022) has been able to clarify,

thanks to marble tests which he has ordered, that instead the entire colossus

of Constantine has been reworked from only one single statue, that had been sculpted from the best quality

of Parian marble, called lychnites.

Because

this original statue had represented Hadrian with bare feet, I have suggested

(cf. supra, in vol. 3-1, pp. 498-499,

726, 729, 737-738, 758) that this statue had represented the divinized emperor,

Divus Hadrianus, and that, in my

opinion, this could possibly have been his cult-statue in the Hadrianeum.

After

this research had been published on our Webserver in the Preview "Hadrian / Konstantin in Rom" (see

Kapitel 8), I have sent this text to some colleagues and friends, asking them

how they themselves judge the bare feet of this colossal portrait of Hadrian.

Lorenzo

Cigaina wrote me the following: "Die Barfüßigkeit könnte wohl auf den

göttlichen bzw. [beziehungsweise] vergöttlichten Status hindeuten, wie man es

bei der berühmten Prima-Porta-Statue des Augustus festgestellt hat".

And John

Pollini answered my relevant question: "In the Prima Porta statue,

Augustus also appears as a hero, one who was mortal but possessed divinity in

life (therefore of a dual nature)".

Eberhard

Thomas, with whom I had discussed the question, how the problem may have been

solved to rework the portrait of the divinized Hadrian, discussed here, into

one of the (still living) Emperor Constantine, alerted me to the fact that the

bare feet of this portrait of Hadrian may have been dressed with sandals (!).

Only after Eberhard's suggestion have I realized that on both feet of the

colossus of Constantine have been sculpted in very low relief the straps of

sandals. I, therefore, suggest as a working hypothesis, that those straps of

sandals may be explained with the transformation of the original portrait of

Hadrian into one of Constantine, and that the straps served as guidelines for

that artist, who added those sandals.

Let's

begin our discussion by looking at the illustrations, which are mentioned in

the Preview "Hadrian / Konstantin

in Rom";

cf.

<https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Konstantin_Hadrian_Koloss_01.html>,

and in

the following text.

Please

note that the coins and medallions, which we publish here, are not illustrated

in their original sizes. For some more figures, which are discussed in the

Preview "Hadrian / Konstantin in

Rom", but not in the following text; cf.

https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Hadrian_Hierapydna_statue.html>.

ILLUSTRATIONS

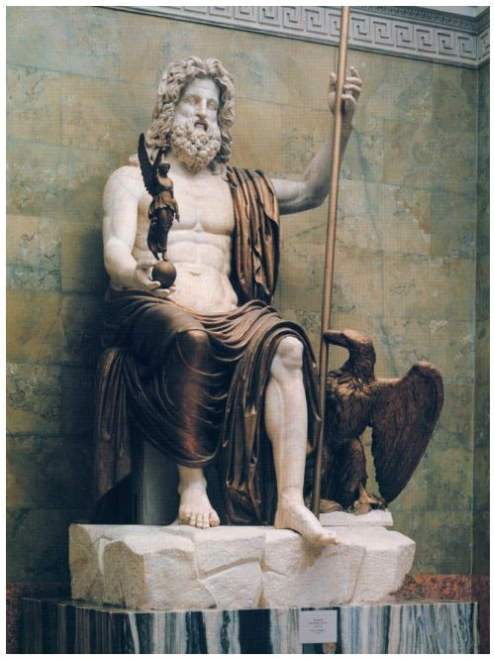

Fig. 10. Colossal acrolithic statue of

Jupiter. St. Petersburg, Hermitage (inv. no. ГР-4155), from Castel Gandolfo.

Height: 3,47 m. From: C. Parisi Presicce (2006b, 146, Fig. 47, copied after M.B.

PIOTROVSKIJ and O.J. NEVEROV 2003, fig. on p. 200).

Fig. 10.1. Giuseppe Antonio Guattani (1805,

Tav. 11), drawing of Vincenzo Pacetti's first restoration of the colossal

marble statue of Jupiter from Castel Gandolfo in the Hermitage at St.

Petersburg (here Fig. 10).

Fig. 11. Colossal acrolithic statue of Hadrian (now Constantine the Great). Roma, Musei Capitolini, Palazzo dei Conservatori,

Cortile. For the nine fragments in the Cortile (MC, inv. 757; inv. 784; inv. 785; inv. 789; inv. 791; inv. 793, inv. 794; inv. 798; MC, dep. 12); cf. C. Parisi

Presicce (2006b). Cf. infra, for the tenth fragment.

C. Evers (1991) has proven that this portrait of Constantine has been reworked from a portrait of Hadrian of his `Rollocken-Portraittypus´.

Compare the right profile of Constantine's head, at which still some of Hadrian's curls called `Rollocken´ are preserved, with the right profile of the portrait

of Hadrian of his `Rollocken-Portraittypus´ in Sevilla, with the same kind of curls; cf. M. Wegner, Hadrian, Plotina, Marciana, Matidia, Sabina,

Berlin 1956, 13: "Sevilla, Museo Arqueologico Provincial, Sala VIIIa", Taf. 11, right.

At the bottom right appears the black and white version of the photo of Constantine's left foot; to the left of it you see the colour photograph.

This black and white photo shows more clearly than the two colour photographs of both feet that on these feet there are represented in very low relief the straps of

sandals. The ten extant fragments of this colossus (cf. here Fig. 11.1, on which they are are all represented) were carved from the best quality of Parian marble,

called lychnites, and were found within and near the Basilica of Maxentius.

The height of the head (without the modern addition of its neck) is 1,74 m. Nine fragments are kept at Roma, Musei Capitolini, Palazzo dei Conservatori,

courtyard.

The tenth fragment, "A portion of the left chest, 126 centimeters high, with the shoulder and arm attachment ... is currently housed in a storage

room of the Parco archeologico del Colosseo (formerly in the first cloister of the Church of Santa Francesca Romana, site of the Antiquarium of the Roman Forum)

[ILL. 18] [my emphasis]"; cf. C. Parisi Presicce (2022, 405, with n. 51. This is the fragment, found by H. Kähler (1951; published by him in 1952).

Photos of the fragments in the courtyard of the Palazzo dei Conservatori: Courtesy of F.X. Schütz (06-III-2020).

Fig. 11.1. "Ricostruzione virtuale del

colosso di Costantino realizzata da Konstantin-Ausstellungsgesellschaft Trier

mbH, Musei Capitolini e ARCTRON3D"; cf. C. Parisi Presicce 2006b, 147,

caption of Fig. 48; cf. p. 127, note *). Courtesy of C. Parisi Presicce.

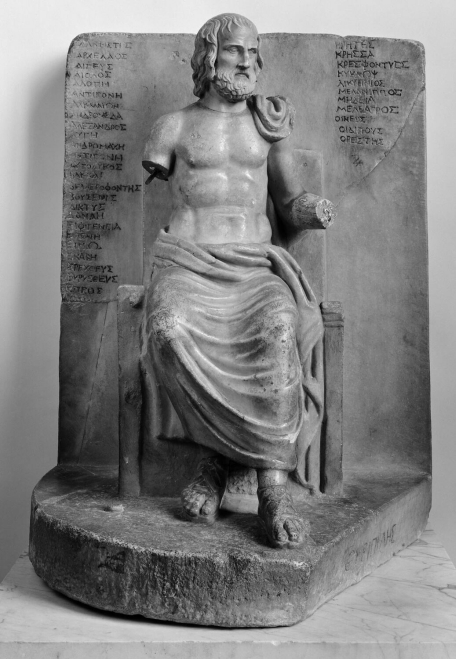

Fig. 12. Statuette of the seated `Euripides´,

marble. Paris, Louvre (MA 343). This figure represented originally Jupiter in

the Capitoline Triad. Cf. H.R. Goette ("From Father god to tragic poet

...", forthcoming).

Photo: © Musée du Louvre, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn / Maurice et Pierre Chuzeville.

Collection: Département des Antiquités grecques, étrusques et romaines.

Permalink: https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010277111 (online: 21.1.2025)

Fig. 13. Statuette of the Capitoline Triad,

marble. Represented are the cult-statues of Domitian's (fourth) Temple of

Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus: Jupiter, Juno and Minerva; the

cult-statue of Jupiter is wearing an oak wreath. Guidonia Montecelio (Roma),

Museo Civico Archeologico `Rodolfo Lanciani´ (inv. no. 80546). Cf. Z. Mari, in:

F. Buranelli (2019, 73: "20. Triade Capitolina Fine del II-inizi III

secolo. Scultura a tutto tondo in marmo lunense, quasi integra (parzialmente

mancanti alcuni arti delle figure e attributi); lungh. cm 119, largh. cm 53, h.

max. cm 80. Dal Comune di Guidonia Montecelio (Rm), loc. Tenuta dell'Inviolata

- Quarto Campanile, Guidonia Montecelio, Museo Civico Archeologico ``Rodolfo

Lanciani´´ (già nel Museo Nazionale di Palestrina fino al 2012). Inv. no.

80546. Furto 1992 (scavi clandestini), Guidonia Montecelio (Roma). Recupero:

1994, Livigno (Sondrio))".

Photo: Triade Capitolina, Museo Civico

Archeologico Rodolfo Lanciani, Guidonia Montecelio Author: Sailko, CC BY 3.0

Deed (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en).

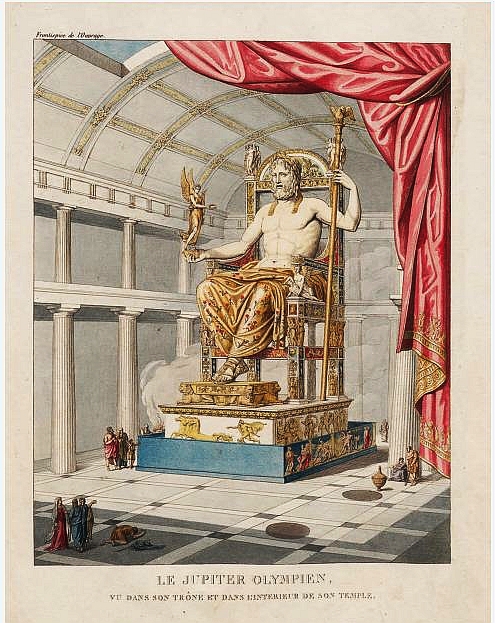

Fig. 14. Reconstruction drawing of the

cult-statue of Zeus in his Temple at Olympia, one of the Seven Wonders of the

ancient (Western) World, a chryselephantine statue made by Phidias (440-430

BC). Coloured lithography by Antoine Chrysostôme Quatremère de Quincy, from his

book Le Jupiter olympien (1815). Cf.

S. Faust (2022, 9-10, "Abb. 1 Zeus von Olympia, Rekonstruktion der Statue

und des Tempelinnenraumes. Farbige Lithographie von A. C. Quatremère de Quincy.

Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg digital, Quatremère de Quincy, 1815,

Frontispiz)".

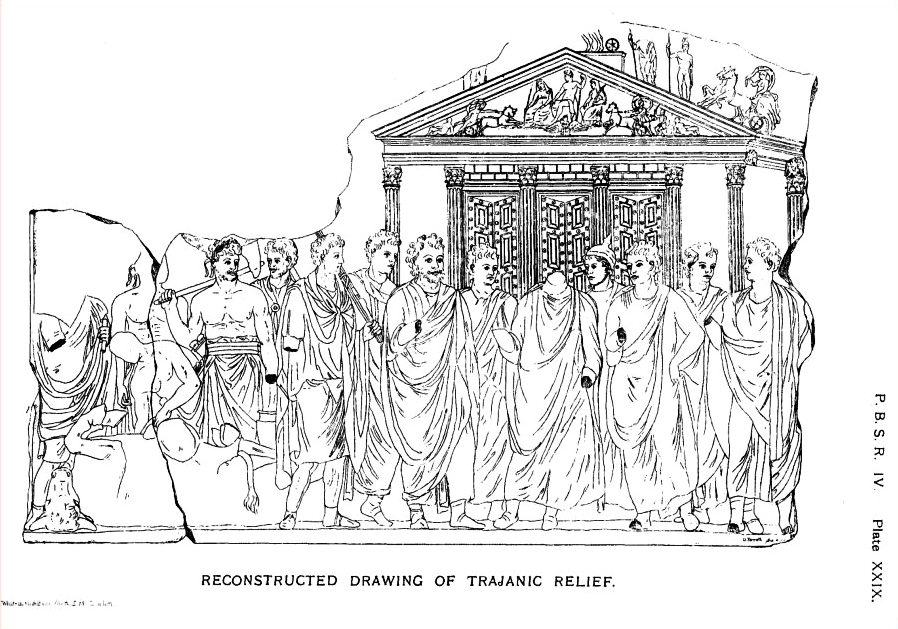

Fig. 16. A.J.B. Wace. Reconstruction drawing

of the Extispicium Relief in the Louvre (MA 978), based on the extant fragments

of this relief, and for the lost parts on Renaissance drawings. The relief

shows the extispicium rite performed

in front of Domitian's (fourth) Temple of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus

and was found in the Forum of Trajan; cf. A.J.B. Wace 1907, 229-244. From:

A.J.B. Wace 1907, 238, Pl. XXIX. Cf. A. Claridge (1998, 238, Fig. 110; ead. 2010, 270, Fig. 113).

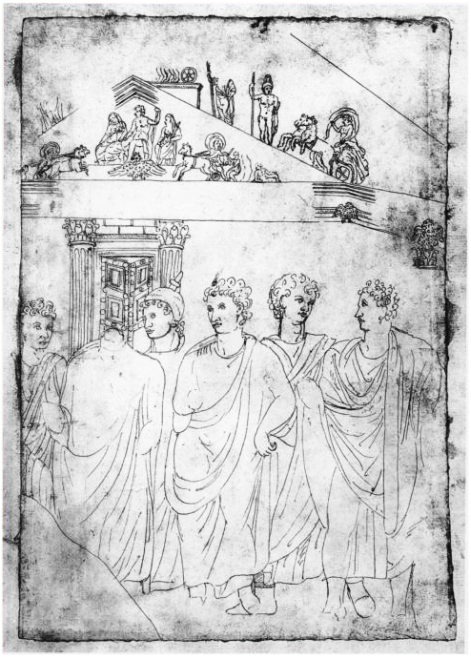

Fig, 17. Renaissance drawing of the right-hand

part of the Extispicium Relief in the Louvre (MA 978), on which in the

background appears the façade of Domitian's (fourth) Temple of Iuppiter Optimus

Maximus Capitolinus. Cod. Vat. Lat. 3439 F. 83. From. A.J.B. Wace 1907, 240, Pl.

XX.

Fig. 17, detail. Renaissance drawing of the

right-hand part of the Extispicium relief in the Louvre (MA 978), on which in

the background appears the façade of Domitian's (fourth) Temple of Iuppiter

Optimus Maximus Capitolinus. Cod. Vat. Lat. 3439 F. 83. From: A.J.B. Wace 1907,

240 Pl. XX. This detail shows part of the pediment of Domitian's Temple of

Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus.

Fig. 19. Marcus Aurelius, `Pietas Augusti´, marble relief, representing a sacrifice in front of Domitian's (fourth) Temple of Iuppiter

Optimus Maximus Capitolinus. Musei Capitolini, Palazzo dei Conservatori, staircase (inv. no. 807/S). Archivio Fotografico dei Musei Capitonini,

Neg. nos. d.13102; d. 13103. Photo: Pasquale Rizzo. © Roma, Sovraintendenza Capitolina ai Beni Culturali. Fig. 19 shows Domitian's

Temple of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus with its pediment. Here are represented the three cult-statues.

The detail of this photo on the right shows Domitian's seated cult-statue of Jupiter Capitolinus,

holding with his right hand his thunderbolt, which is lying on his lap.

Fig. 19a. Marcus Aurelius, `Pietas Augusti´,

marble relief, representing the sacrifice at the end of Marcus Aurelius'

triumph (of AD 176), celebrated in front of Domitian's (fourth) Temple of

Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus. Musei Capitolini, Palazzo dei

Conservatori, staircase (inv. no. 807/S). From: T. Hölscher (2016, 302, Abb.

9.4): "Triumph-Opfer des Marc Aurel auf dem Kapitol. Nach: I. Scott Ryberg,

Panel Reliefs of Marcus Aurelius (1967) pl. XV". R. Bianchi Bandinelli and

M. Torelli (1976, "Arte Romana", scheda 142) wrote: "si tratta

del sacrificio prescritto al termine del trionfo".

Fig. 20. Marble statuette of M. Bossert's

(2000) statue-type "Iuppiter Capitolinus". Rome, Via Appia Nuova. The

caption of M. Bossert's Abbildung 14, which is illustrated here, reads:

"Iuppiter Capitolinus von der Via Appia Nuova, Rom (Italien). Marmor,

H[öhe] 80 cm".

Fig. 20.1. Bronze statuette representing the `Capitoline

Jupiter´, datable to the 1st or 2nd century AD.

Cf. S. Faust (2022, 22-24, Abb.

4: "Bronzestatuette des Jupiter Capitolinus 1.-2. Jh. n. Chr., New York,

Metropolitan Museum of Art

(Open Access/Public Domain [CCO]

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/246686)". (online: 21.1.2025)

Fig. 83. Denarius,

issued by Domitian in Rome in AD 95/96, London, British Museum (BMC 242),

reverse, representing Domitian's (fourth) Temple of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus

Capitolinus. Only on the denarius of

the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, which is also illustrated here, it is

very well visible that Domitian's seated cult-statue of Jupiter Capitolinus is

holding with his right hand his thunderbolt that is lying on his lap.

Cf. R.H. Darwall-Smith (1996, 107-110, 280,

Fig. 34 on Plate XX): Unfortunately we were unable to verify Darwall Smith's

assertion that the coin, which he discusses and illustrates, is kept in the

Ashmolean Museum. There are altogether four copies of this coin known: at the

"American Numismatic Society; Bibliothèque Nationale de France;

Münzkabinett Berlin; and the British Museum", but the copy illustrated by

Darwall-Smith (op. cit.) is not among

those four coins. For this list, and for illustrations of the first three

coins; cf. http://numismatics.org/ocre/id/ric2_1(2).dom.815 [9-X-2024].

For the copy of this coin in the British

Museum, illustrated here; cf. C. Parisi Presicce and E. Dodero (2023, 67, ns. 31, 32, Fig.

3 [= here Fig. 83] cf. supra, in vol.

3-1, pp. 720-723): The British Museum, Museum number R.11170. "Obverse:

Head of Domitian, bare, right. Inscriptions: DOMITIANVS AVG GERM and IMP CAESAR

(inscription on architrave). Reverse: Temple of Capitoline Jupiter, six

columns, with Jupiter seated and two figures flanking him, between columns".

RE2 / Coins of the Roman Empire in the British Museum, vol. II: Vespasian to

Domitian (242, p. 346); RIC2.1 / The Roman Imperial Coinage, vol.2 part 1: From

AD 69 to AD 96: Vespasian to Domitian (815, p. 325).

© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared

under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International

(CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

Courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale de

France. Public domain.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10447826z (22.1.2025)

Cf. supra,

in volume 3-1, pp. 1268-1270, in: The

first Contribution by Peter Herz on the inscription (CIL VI 2059.11), which reports on a meeting of

the Arval brethren on 7th December 80 at the Temple of Ops in Capitolio, among them Titus and Domitian: Titus vows

to restore and dedicate what would become Domitian's (fourth) Temple of

Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus; see below, in: Appendix I.g.1.) Domitian's denarii, issued in AD 95/96, documenting some of the buildings he erected at

Rome (cf. here Figs. 80-84), inter alia

allegedly representing his Temple of Iuppiter Custos. These coins show in

reality Domitian's Temple of Isis and his Temple of Serapis within his Iseum

Campense and his Temple of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus ...; see

also below, in: Appendix I.g.4.) Domitian's sacellum of Iuppiter Conservator, his Temple of Iuppiter Custos, and his

(fourth) Temple of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus (cf. here Fig. 83). With The first Contribution by Peter

Herz.

Fig. 156. Reconstruction at the scale 1 : 1 of

the colossal acrolithic statue of Hadrian (now Constantine the Great) at the

Musei Capitolini in Rome, in the Giardino di Villa Caffarelli. For a detailed

documentation, why and how the reconstruction was created in this way: cf. C. Parisi Presicce (2022).

Since the 6th of February 2024 it is on display there. H: allegedly circa 13 m. In reality, this

statue is only a maximum of 10 m high, as the comparison with me on this photo

shows: I am 1,68 m `high´ (comprising my shoes).

This reconstruction was based on the 10 extant

fragments of this colossal portrait; cf. here, Figs. 11; 11.1.

In the following, I will quote some passages

from the following Press Release:

"Comunicato Stampa, ROMA, Assessorato

alla Cultura, Sovrintendenza Capitolina ai Beni Culturali, MUSEI IN COMUNE

ROMA, and FACTVM FOVNDATION FOR DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY IN PRESERVATION, Roma, 6

febbraio 2024":

"La statua, alta circa 13 metri, è stata

realizzata attraverso tecniche di ricostruzione innovative, partendo dai pezzi

originali del IV secolo d.C. conservati nei Musei Capitolini ...

la straordinaria ricostruzione del Colosso in

scala 1:1, [è] risultato della collaborazione tra la Sovrintendenza Capitolina,

Fondazione Prada e Factum Foundation for Digital Technology in Preservation con

la supervisione scientifica di Claudio Parisi Presicce, sovrintendente

capitolino ai Beni Culturali ...

Il Giardino di Villa Caffarelli, dove è stata

collocata la riproduzione del Colosso di Costantino, insiste in parte sull'area

occupata dal Tempio di Giove Ottimo Massimo, che un tempo ospitava la statua di

Giove, la stessa forse da cui il Colosso fu ricavato o che comunque ne

costituisce il modello di derivazione. I resti del tempio sono oggi visibili

all'interno dell'Esedra di Marco Aurelio ...

I nove frammenti in marmo pario, attualmente

conservati presso i Musei Capitolini, sono stati rinvenuti nel 1486 ... Un

decimo frammento, parte del torace, rinvenuto nel 1951 [this is the fragment,

found by Heinz Kähler, which he has published in 1952], è in procinto di essere

trasferito dal Parco Archeologico del Colosseo nel cortile del Palazzo dei

Conservatori, accanto agli altri frammenti ...

La complessa operazione di ricostruzione

realizzata da Factum ha tenuto conto di molteplici fattori ... Dopo aver

ultimato il modello 3D ad altissima risoluzione, si è poi proceduto con la

ricostruzione materiale del Colosso. Resina e poliuretano, insieme a polvere di

marmo, foglia d’oro e gesso, sono stati scelti come materiali per rendere le

superfici materiche del marmo e del bronzo, mentre per la struttura interna ...

è stato impiegato un supporto in alluminio facilmente assemblabile e

rimovibile". Photo: Courtesy of F.X. Schütz (23-IV-2024).

Fig. 157a. Two Sestertii, issued by Vespasian in Rome in 76 AD (RIC II 577, BMCRE 721, pl. 29.6 [= Fig. 157a, left];

and BMCRE 722, pl. 29.5 [= Fig. 157a, right]).

"Bibliographic references: RE2 / Coins of the Roman Empire in the British Museum, vol.II: Vespasian to Domitian (721, p.168)

RIC2.1 / The Roman Imperial Coinage, vol.2 part 1: From AD 69 to AD 96: Vespasian to Domitian (886, p.123)"

RE2 / Coins of the Roman Empire in the British Museum, vol.II: Vespasian to Domitian (722, p.168)

Both coins are described as follows: "Copper alloy coin , sestertius, Minted in: Rome (city), 76 AD".

Obverse: "Head of Vespasian, laureate, right, Inscription content: IMP CAES VESPASIAN AVG P M TR P P P COS VII".

Reverse: "Temple of Capitoline Jupiter with six columns. Inscription content: S C"

The reverses of these coins show that the cult-statue of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus in Vespasian's (third) temple of the god was

holding with his right hand the thunderbolt which was lying on his right thigh.

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/C_R-10631 (22.1.2025)

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/C_1872-0709-480

© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

Fig. 158. Bronze medallion of Commodus, issued

in Rome. From: B. Bergmann (2010a, 79, 389-390, Kat. Nr. 63, Abb. 27). Date:

"10.-31.12. 183 n. Chr.; Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France; Avers:

Kopf des Commodus nach re[chts] mit Kranz. Bei dem Kranz handelt es sich um

einen dichten Lorbeerkranz, der hinten mit einem Band in einer deutlich

sichtbaren Schleife geschlossen ist. Die Enden des Bandes fallen im Nacken

herab. Li[nks]: M AVREL COMMODVS; re[chts] ANTONINVS AVG PIVS; Revers: Kopf des

bärtigen Iuppiter nach re[chts] mit Kranz. Bei diesem Kranz handelt es sich um

einen dichten Eichenkranz ohne Tänie, in dem verschiedentlich auch Eicheln

dargestellt sind; Li[nks] unten: IOM ...

ABBILDUNG: Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de

France (Monnaies Médailles et Antiques [Me 260])".

Let's

now turn to the first Chapter of my new Text:

I.) Claudio Parisi Presicce's hypothesis (2022), according to which

the colossal portrait of Constantine (here Figs.

11; 11.1; 156) has been reworked from Domitian's (fourth) cult-statue of

Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus, cannot possibly be true, and that for the

following reasons. As observed by Birgit Bergmann (2010a), this cult-statue of

Jupiter (cf. here Figs. 13; 158) was

crowned with an oak wreath, a fact that was previously unknown to me. The

portrait of Constantine (here Fig. 11),

on the other hand, has certainly never worn a wreath.

In

addition, this text contains summaries of subjects, that are discussed in the

following Chapters of the Preview "Hadrian

/ Konstantin in Rom"; cf. Kapitel 1: the motivation to write this

text: Claudio Parisi Presicce's (2022) reconstruction of the colossus of

Constantine (here Fig. 156); Kapitel

2, at point 1.): Cécile Evers's proof, that the head of the colossus of

Constantine (here Fig. 11) has been

reworked from a portrait of Hadrian; Kapitel 2, at point 1.)-Kapitel 7: Parisi

Presicce's (2005; 2006a; 2006b; 2022) observations concerning Domitian's

(fourth) cult-statue of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus; Kapitel 2, at

point 2.): the four Temples of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus

and their four cult-statues; Kapitel 3: the copies of Domitian's (fourth)

cult-statue of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus; Kapitel 5-Kapitel 6:

Parisi Presicce's (2006b; 2022) observations concerning the statue of

Constantine in Rome, which has been described by Eusebius (Hist. Eccl. 9,9,10-11); Kapitel 6-Kapitel 7: Parisi Presicce's

(2022) suggestion, that the colossus of Constantine (here Figs. 11; 11.1; 156) has been reworked from Domitian's (fourth)

cult-statue of Jupiter Capitolinus, and my rejection of this hypothesis;

Kapitel 9: my own hypothesis, that the colossus of Constantine has possibly been

reworked from the cult-statue of Divus

Hadrianus in the Hadrianeum.

See

Birgit Bergmann 2010a, Der Kranz des

Kaisers. Genese und Bedeutung einer römischen Insignie (Berlin/ New York:

Walter de Gruyter 2010).

Bergmann

(2010a, writes on the "Innenseite hinterer Buchdeckel") about the

meaning of oak wreaths:

"Kranz - Bedeutungen

...

Eichenkranz

(corona ilignea, quernea, quercea) 1.

KULT: a) Kranz bei Kulthandlungen (vgl. z.B. [vergleiche zum Beispiel] Opfer an

Ceres). b) Kranz des domitianischen Kultbildes

des Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus. 2. SPIELE: Siegerpreis der von

Domitian initiierten Capitolia ... [my emphasis]".

Concerning

the "Siegerpreis" at the Capitolia, inaugurated by Domitian in AD 86,

which consisted in an oak wreath, Birgit Bergmann (2010a, 73-74, with n. 268,

Section: "Das Aussehen der corona

Etrusca") writes:

"Zusätzlich meinte man, auch zwischen dem

Eichenkranz und Iuppiter eine enge Verbindung belegen zu können [with n.

268], da dem Sieger des von Domitian

gegründeten agon Capitolinus ein

solcher [page 74] Eichenkranz

verliehen wurde [with n. 269]".

In her note 268, Bergmann writes: "Vgl.

[vergleiche] Versnel (1970) 76; Alföldi (1985) 155ff.".

In her note 269, she writes: "Vgl. z.B.

[vergleiche zum Beispiel] Mart. 4, 1, 6. 54, 1f., Iuv. 6, 387 und Fiebiger

(1901) 1642 mit ausführlichem Zitat der relevanten Belegstellen

sowie unten Anm. 303".

In her note 303, she writes: " Vgl.

[vergleiche] Mart. 4, 1, 6. 54, 1; 9, 23, 5, Stat. silv. 5, 3, 231 und Iuv. 6,

387 sowie oben Anm. 269".

Cf.

Andreas Alföldi, Caesar in 44 v. Chr. I:

Studien zu Caesars Monarchie und ihren Wurzeln, Antiquitas III 16 (Bonn: Habelt 1985); Fiebiger, RE IV 2 (1901)

1636ff. s.v. Corona (H.O. Fiebiger).

Before

reading Birgit Bergmann's (2010a, 73-74) statement that the

"Siegerpreis" (i.e., the prize) in the Capitolia (also referred to as

agon Capitolinus and as `Capitoline

Games´), which Domitian inaugurated in AD 86, consisted in an oak wreath, I had

ignored this fact. None of the scholars, whose works I had consulted for the

Capitolia, mentions this prize (cf. supra,

in vol. 3-1, pp. 143, 154-155, 173-174, 233-234).

Bergmann

(2010a, 79), after discussing the question, whether or not any of the three

cult-statues of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus in the first three temples

of the god, had been wearing a wreath, comes to the conclusion that this had

not been the case. Domitian's (fourth) cult-statue of Jupiter Capitolinus was

the first one to be crowned with a wreath, and we also know that this was an

oak wreath.

For all

four Temples of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus, and for their four

cult-statues; cf. Preview "Hadrian

/ Konstantin in Rom", Kapitel 2, at point 2.));

cf.

<https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Konstantin_Hadrian_Koloss_02.html>.

Bergmann

(2010a, 79) writes:

"Erst in domitianischer Zeit scheint ein

gravierender Eingriff in die Ikonographie des höchsten Staatsgottes vorgenommen

worden zu sein, nachdem der capitolinische Tempel 80 n. Chr. erneut einem Feuer

zum Opfer gefallen war: Das Kultbild des Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus

erhielt nun offensichtlich zum ersten Mal einen Kranz. Denn auf einem unter

Commodus ausgegebenen Bronzemedaillon, das den Kopf dieses domitianischen

Kultbildes zeigt, trägt der Gott einen Eichenkranz (vgl. [vergleiche] Kat. Nr.

63, Abb. 27 [= here Fig. 158]) [with n. 302; my emphasis]".

Bergmann

(2010a, 79, n. 302) provides references and further discussion. She calls this

medallion of Commodus (here Fig. 158)

the only "Primärquelle" proving her suggestion that Domitian's

cult-statue of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus had been crowned with an

oak wreath. But she adds that this is so far a mere hypothesis which could only

be verified by looking at all available representations of Jupiter Capitolinus

which, for lack of time, she could not possibly do in the context of this

Study:

"Zur Ikonographie des domitianischen

Kultbildes allgemein vgl. [vergleiche] Martin a. O. (1987) 133 ff.; Krause

(1989) 149 ff. ...

Im Gegensatz dazu gibt es für das

domitianische Kultbild nur eine einzige `Pimärquelle´: das Medaillon des

Commodus Kat. Nr. 63. Die Annahme, daß

das domitianische Kultbild einen Eichenkranz getragen hat, ist daher zunächst

lediglich als Hypothese zu betrachten. Eine Möglichkeit, diese besser

abzusichern, wäre eine Durchsicht aller Denkmäler, die sich mit den jeweiligen

Iuppiter-Capitolinus-Statuen in Verbindung bringen lassen ... Eine solche

Durchsicht aller Iuppiterbilder ist im Rahmen der vorliegenen Studie jedoch

nicht zu leisten [my emphasis]". - To

this I will come back below.

Cf. Hanz

Günther Martin, Römische Tempelkultbilder

: eine archäologische Untersuchung zur späten Republik (Roma:

<<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER, 1987); Bernd Harald Krause, Trias Capitolina. Ein Beitrag zur

Rekonstruktion der hauptstädtischen Kultbilder und deren statuentypologischer

Ausstrahlung im Römischen Weltreich (Trier: University publication 1989).

Bergmann

(2010a, 389-390) writes:

"Kat. Nr. 63 Das Bronzemedaillon des

Commodus (Abb. 27 [on p. 79 = here Fig.

158])

PRÄGESTÄTTE:

Rom.

DATIERUNG:

10.-31. 12. 183 n. Chr.

AO

[Aufbewahrungsort]: Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

NOMINAL:

Medaillon.

MATERIAL:

Bronze.

AV

[Avers]: Kopf des Commodus nach re[chts] mit Kranz. Bei dem Kranz handelt es

sich um einen dichten Lorbeerkranz, der hinten mit einm Band in einer deutlich

sichtbaren Schleife geschlossen ist. Die Enden des Bandes fallen im Nacken

herab.

Li[nks]:

M AVREL COMMODVS; re[chts] ANTONINVS AVG PIVS.

RV [Revers]: Kopf des bärtigen Iuppiter nach

re[chts] mit Kranz. Bei diesem Kranz handelt es sich um einen dichten

Eichenkranz ohne Tänie, in dem verschiedentlich auch Eicheln dargestellt sind.

Li[nks] unten: IOM. [page 390]

LITERATUR:

F. GNECCHI, I medaglioni romani II (1912) 56 Kat. Nr. 41 Taf. 81,2; W.

Szaivert, Die Münzprägung der Kaiser Marcus Aurelius, Lucius Verus und Commodus

(161-192), Moneta Imperii Romani 18 (1986) 49 Nr. 1101; 186; 218 Taf. 11,15;

Krause (1989) 152 ff. Taf. 207, 2.

ABBILDUNG:

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France (Monnaies Médailles et Antiques [Me

260]) [my emphasis]".

That the

head of Jupiter, represented on the medallion of Commodus (here Fig. 158) is wearing an oak wreath, as suggested by Bergmann

(2010a, 389) is very well visible: this is obviously her own observation,

because Bernd Harald Krause (1989, 152 ff.), whom she quotes for this

medallion, does not mention this oak wreath. My thanks are due to Franz Xaver

Schütz, who has found Krause's Dissertation (1989) for me.

Birgit Bergmann's (2010a, 79, n. 302) above-quoted

statement that the medallion of Commodus (her Kat. Nr. 63, Abb. 27 = here Fig.

158) is the only `Primärquelle´, proving her hypothesis that Domitian's

(fourth) cult-statue of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus was wearing an oak

wreath, is fortunately not true.

Bergmann (2010a) herself publishes unwittingly a second such `Primärquelle´,

which is why thanks to the huge collection of wreaths, published in her book,

Bergmann has herself proven, with a second such `Primärquelle´, that Domitian's

cult-statue of Jupiter was actually wearing an oak wreath. - Besides, contrary

to Bergmann's (2010b, 79, n. 302) own above-quoted statement, in my opinion,

she had already proven this hypothesis with her first `Primärquelle´. What do I

mean with this second `Primärquelle´? Domitian's Capitoline Triad in Guidonia

Montecelio (here Fig. 13) !

Franz

Xaver Schütz has alerted me to the fact that Bergmann (2010a, 462, in her

Section "Eichenkranz"), among the representations of Jupiter wearing

an oak wreath, known to her, has also listed the statuette of Jupiter (here Fig. 13), which was at first on display

at the Museo Nazionale at Palestrina, but that, since 2012, is kept in the

Museo Civico Archeologico Rodolfo Lanciani, at Guidonia Montecelio.

Birgit

Bergmann (2010a, 462: "Tabelle C: Iuppiterdarstellungen (ohne Numismatik;

basierend auf LIMC VIII 1 [1997] 421ff. s.v. Zeus/Iuppiter {F. Canciani - A.

Costantini]) writes:

...

Eichenkranz

...

LIMC Nr.

479; Aufbewahrungsort Palestrina Mus.

Naz.; Fundort Guidonia, röm.[ische]

Villa; Gattung Statuette [my emphasis]".

After

reading Birgit Bergmann's (2010a, 462) relevant statement, I looked again at

the photo of this statuette (here Fig.

13) and realized that she is right. I must confess that, although I know

this statuette of Jupiter from autopsy, I had so far not noticed his oak wreath

(!).

Note that the head of Domitian's Jupiter

Capitolinus, which is represented on Commodus's medallion; cf. Bergmann (2010a,

79, Abb. 27 = here Fig. 158), and the head of Jupiter of Domitian's Capitoline

Triad (here Fig. 13) are endowed with the same, very elaborate coiffures and

beards, which is why both were certainly copied after the same prototype.

Bergmann

(2010b, 462) knows that this statuette of Jupiter (here Fig. 13), which was found at Guidonia, at the time, when the LIMC VIII (1997) was published, was on

display in the Museo Nazionale at Palestrina. As mentioned above, this Jupiter

is now since 2012 in the Museo Civico at Guidonia Montecelio. For the thrilling

history of this statuette; cf. the caption of here Fig. 13; and supra, in

vol. 3-1, pp. 698-700.

But

Bergmann (2010b, 462) is unaware of the facts, that a) this Statuette of

Jupiter belongs to a Capitoline Triad, and b) that Filippo Coarelli (2009) has

convincingly suggested in his catalogue Divus

Vespasianus that this Capitoline Triad is a copy of Domitian's cult-statues

of his (fourth) Temple of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus.

Cf. supra, in vol. 3-1, p. 700: ``Filippo

Coarelli (in: F. COARELLI 2006a, 514, cat. 118:) "Gruppo in marmo della

Triade Capitolina" (cf. here Fig.

13), which at the time (until 2012) was kept at Palestrina, Museo

Archeologico Nazionale Prenestino (inv. no. 80546)´´.

On 23rd

December 2024, I called Filippo Coarelli in Perugia to tell him that the

Jupiter of Domitian's Capitoline Triad in the Museum of Guidonia Montecelio is

wearing an oak wreath. He told me that he knew this already, but that,

unfortunately, he had not mentioned this fact in his text in his catalogue Divus Vespasianus (2009) (!).

Conclusions

Why I am telling you Birgit Bergmann's

observation (2010a) that Domitian's cult-statue of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus

Capitolinus was wearing an oak wreath ? - Which, as we have learned above, is

visible on the medallion of Commodus (here Fig. 158), and on the head of

Jupiter in Domitian's Capitoline Triad in the Museo Civico at Guidonia

Montecelio (here Fig. 13), both published by Birgit Bergmann (2010a).

Because this fact proves that the colossal

portrait of Constantine in the Palazzo dei Conservatori (here Figs. 11; 11.1;

156), cannot possibly have been reworked from Domitian's cult-statue of Jupiter

Capitolinus - as suggested by Claudio Parisi Presicce (2022, 395, 396). The

reason being that the head of this colossus of Constantine has certainly never

been wreathed.

For

photos of the colossal portrait of Constantine (here Figs. 11; 11.1; 156), which prove this fact;

cf.

<https://fortvna-research.org/photos/Fragmente_Kolossalstatue_Konstantin_ehemals_Hadrian.html>.

In the

Preview "Hadrian / Konstantin in

Rom", Kapitel 1, is mentioned the reason, why I had conducted the

research that is summarized in this text;

cf.

<https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Konstantin_Hadrian_Koloss_01.html>:

``In volume 3-1, I have summarized the scholarly

discussion, at the time known to me, that concerns this statue of Constantine,

and I maintain my judgement, following Cécile Evers (1991), that this colossal

statue was recarved from a portrait of Hadrian. I also maintain my tentative

suggestion that this colossal statue of Hadrian could have been the cult-statue

of Divus Hadrianus in the Hadrianeum (cf. supra, in volume 3-1, 498-499, 726, 729, 737-738, 758).

Cf. supra, in volume 3-1, p. 724 ff., at A Study

on the colossal portrait of Hadrian (now Constantine the Great) in the

courtyard of the Palazzo dei Conservatori at Rome (cf. here Fig. 11). With The Contribution by Hans Rupprecht

Goette on the reworking of the portrait of Hadrian (now Constantine the Great).

But I had overlooked the publication by

Claudio Parisi Presicce (2022), in which he suggests that this portrait of

Constantine was instead created by reworking Domitian's (fourth) cult-statue of

Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus. Therefore, this article by Parisi

Presicce will be discussed in the following. My thanks are due to Claudio

Parisi Presicce, who has been so kind as to send me this article ...

Cf. Claudio Parisi Presicce: "From Jupiter

to Constantine: A Marble Colossus Reused, Dismembered, `Reconstructed´",

in: Salvatore Settis und Anna Anguissola (eds.), exhibition-catalogue Recycling Beauty (Milano: Fondazione

Prada 2022), 389-417 (comprising the catalogue texts "46" and

"47"); cf. pp. 548-555 ("Texts in Italian").

In my discussion of Parisi Presicce's

hypotheses, I have also considered the contribution by Adam Lowe of the Company

Factum Foundation for Digital Technology

in Preservation:

"47 Reconstruction

of the Colossus of Constantine 2022 ...", in: Parisi Presicce 2022,

411-413 (within his catalogue text "47"). This Company has created

the reconstruction of the colossus of Constantine at the scale 1:1 (cf. here

Fig. 156)´´.

Let's

begin our survey with the ancient reliefs and sculptures in the rounds,

representing Domitian's (fourth) cult-statue of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus,

that were already known to me, when I wrote the Preview "Hadrian / Konstantin in Rom", Kapitel 3:

``3.)

Domitian's (fourth) cult-statue of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus is

known from two ancient marble reliefs, four marble statuettes, and one bronze

statuette´´;

cf.

<https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Konstantin_Hadrian_Koloss_03.html>.

Of the

Extispicium Relief in the Louvre at Paris some fragments were found in the

Forum of Trajan, and some of its fragments are known from Renaissance drawings

(cf. here Figs. 16; 17); Marcus

Aurelius's relief `Pietas Augusti´ is on display in the staircase of the

Palazzo dei Conservatori (here Figs. 19;

19a).

The

first relief (here Figs. 16; 17)

shows the performance of the Extispicium rite in front of Domitian's Temple of

Jupiter Capitolinus. The pediment of this Temple was also represented on one of

the fragments of this relief, which is now lost, but fortunately a Renaissance

drawing of this fragment has survived (here Fig. 17, detail). This drawing shows that the cult-statue of

Jupiter, together with the cult-statues of Juno and Minerva, was also

represented in the pediment of this temple. Jupiter's right hand lies on his

right thigh; the drawing shows also, that Jupiter's left knee and left leg are

not covered by his garment. On the relief of Marcus Aurelius (here Figs. 19; 19a), the pediment of

Domitian's Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, which appears in the background, is

still extant: it shows a representation of the cult-statue of Jupiter, again

together with the cult-statues of Juno and Minerva: Jupiter is holding his

thunderbolt with his right hand that is lying on his right thigh.

But we

can also see that in both reliefs (here Figs.

16; 17; 19; 19a) the cult-statue of Jupiter is not represented as wearing

an oak wreath. In all the representations of Domitian's Jupiter Capitolinus,

mentioned here, the god holds with his raised left hand his long sceptre.

As we have learned above, the statuette of

Jupiter in Domitian's Capitoline Triad in the Museo Civico at Guidonia

Montecelio (here Fig. 13) is actually wearing an oak wreath.

For the

other replica of Domitian's Capitoline Triad in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum

Trier (Inv. Nr. ST 3196), published by Hans Rupprecht Goette ("From Father

god to tragic poet ...", forthcoming) this is not true. My thanks are due

to Hans Rupprecht Goette, who has confirmed this fact by E-mail on 15th January

2025. Also the other statuettes, copying Domitian's cult-statue of Jupiter

Capitolinus, are not shown as wearing an oak wreath.

These

replicas of Domitian's cult-statue of Jupiter Capitolinus are: Martin Bossert's (2000, 21-22

with n. 22, Abb. 14 [here Fig. 20])

marble statuette of his statue-type "Iuppiter Capitolinus", Rome, Via

Appia Nuova; also this statuette of Jupiter shows the god with exposed left

knee and left leg, and the god is again holding his thunderbolt with his right

hand that is lying on his right thigh; and the bronze statuette in the

Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City (here Fig. 20.1), published by Stephan Faust (2022, 22-24, Abb. 4): also

this bronze statuette of Jupiter Capitolinus is holding a thunderbolt with his

right hand that is lying on his right thigh.

In the following, I quote in an English

summary that part of the Preview "Hadrian / Konstantin in Rom",

Kapitel 3;

cf.

<https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Konstantin_Hadrian_Koloss_03.html>;

- in which, based on the above-summarized

discussion of the marble reliefs and statuettes (here Figs. 12; 13; 16; 17; 17,

detail; 19; 19a; 20; 20.1), which represent Domitian's (fourth) cult-statue of

Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus, I have suggested that also the colossal

statue of Jupiter in the Ermitage at St. Petersburg (here Fig. 10) is a copy of

Domitian's cult-statue of Jupiter Capitolinus.

``These

marble reliefs, the marble statuettes and the bronze statuette prove that

Domitian's cult-statue of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus was copied

after a seated prototype of Jupiter (cf. here Fig. 13), in which the god held his sceptre with his left raised

hand, and with his right hand his thunderbolt, which was lying on his right

thigh (cf. supra, in volume 3-1, pp.

698-723, especially pp. 700-707, 712, 718-719).

Contrary

to the just-mentioned copies of Domitian's cult-statue of Jupiter Capitolinus

(here Fig. 13), the portrait-statue

of Hadrian (now Constantine the Great; here Figs. 11; 11.1; 156) was copied after a prototype of Jupiter, which

showed the seated god in a reversed image of the cult-statue of Iuppiter

Optimus Maximus Capitolinus - that was copied much more frequently. In the case

of the statue-type of Jupiter, after which the colossus of Hadrian/

Constantine was copied (here Figs. 11; 11.1; 156), the god holds his

sceptre with his raised right hand and holds with his left hand his (other)

attribute.

For the

very different numbers of replicas of both prototypes of Jupiter; cf. supra, in vol. 3-1, p. 707.

The colossal statue of Jupiter in the Ermitage

of St. Petersburg (Inv. Nr. ГР-4155; here Fig. 10), from Domitian's Villa on Lago Albano called Albanum; cf. Parisi Presicce (2022, 389,

ILL. 1), holds his sceptre with his raised left hand, and his left knee and

left lower leg are exposed. With his right hand, originally lying on his right

thigh, he was holding his thunderbolt. This statue of Jupiter, therefore,

copies, in my opinion, likewise Domitian's (fourth) cult-statue of Iuppiter

Optimus Maximus Capitolinus.

Cf. supra, in vol. 3-1, pp. 60-61, 708-709.

For the meaning of the exposed left knee and left lower leg of this statue of

Jupiter (here Fig. 10); cf. supra, in vol. 3-1, pp. 709-710 (inter alia with summaries of the earlier

relevant studies of C. PARISI PRESICCE); see now in much more detail: Parisi

Presicce (2022, 389-393).

That the statue of Jupiter at St. Petersburg

(here Fig. 10) may be regarded as a copy of Domitian's cult-statue of Iuppiter

Optimus Maximus Capitolinus, is certain for the following, interrelated

reasons:

a) the entire right arm and right hand of this statue (comprising

the globe, held in the right hand, surmounted by a statuette of Victory), are

modern restorations. See Massimiliano Papini (2020, 30 with Fig. 14 [= here Fig. 10.1]), to whom we owe the

information, that the statue had been found without its right arm and without

its head; and Anna Trofimowa (2020, 77-78, from whom we learn that the statue

had been found without its right hand. For both; cf. supra, in vol. 3-1, pp. 60-61, 706, 718). My thanks are due to Hans

Rupprecht Goette, who was kind enough to send me those two publications;

b) Massimiliano Papini (2020, 30 with n. 30, Fig. 14 [= here Fig. 10.1]; cf. supra, in vol. 3-1, pp. 82-83, 718) quotes from the first find

report of this statue of Jupiter at St. Petersburg and mentions the first

drawing of the (already restored) statue by Giuseppe Antonio Guattani, who has

also published this drawing (cf. G.A. GUATTANI, Monumenti antichi ovvero notizie sulle antichità e belle arti di Roma

per l'anno 1805, 1805, pp. LIV-LIX, Tav. XI [= here Fig. 10.1]). Guattani saw this statue of Jupiter in the Studio of

Vincenzo Pacetti; his drawing and his text are for us of so great importance,

because he has documented with them Pacetti's first restoration of this statue

of Jupiter. Guattani was obviously unaware of the fact that (when he drew the

statue) Pacetti had already restored great parts of it, otherwise Guattani had

certainly not written in his text (cf. id.

1805, pp. LVIII-LIX) that Pacetti would only soon restore this statue (!).

My

thanks are due to Franz Xaver Schütz, who has found Guattani's publication

(1805) for me on the Internet; cf. here Fig.

10.1. In Guattani's drawing this statue of Jupiter raises its left arm and

holds with its left hand the sceptre, whereas the right arm is lowered and his

right hand is lying on his right thigh. Guattani draws also the head of the

statue and describes the head, the right arm and the right hand as being

ancient, and that although the statue had been found without its right arm and

right hand, and without its head. The head and the right arm of this statue of

Jupiter, comprising the right hand, were, therefore, obviously very convincing

restorations of Pacetti, which still Oskar Waldhauer (1928; see below) should

(erroneously) judge as being ancient;

c) we can also conclude something else when looking at Vincenzo

Pacetti's first restoration of the statue of Jupiter now at St. Petersburg, as

drawn by Guattani (here Fig. 10.1),

and when we look at the statue of Jupiter in its current state (here Fig. 10); cf. supra, in vol. 3-1, pp. 60, 61, 704, 706, 718, 719 (the quotation

is from p. 61):

We learn from Anna Trofimowa (2020, 77-78)

that the statue (here Fig. 10) had first been restored by Vincenzo Pacetti,

holding a thunderbolt in its right hand: since its right thigh is ancient, my

guess is that Pacetti had seen remains of this thunderbolt on the right leg of

the god [my emphasis].

Contrary

to the here just-mentioned new observations concerning the statue of Jupiter in

the Ermitage (here Fig. 10), Claudio

Parisi Presicce has not realized that the complete right arm of this statue of

Jupiter is a modern restoration, and that the restoration of its right hand

with the globe, surmounted by a standing statuette of Victory, has intentionally

been copied after the statue of Zeus in his temple at Olympia (here Fig. 14); See Parisi Presicce (2006b,

144-145; cf. supra, in vol. 3-1, p.

719; and Parisi Presicce 2022, 390´´.

Parisi

Presicce's (2022, 390) believes instead that the globe, surmounted by a

statuette of Victory, may be regarded as the original attribute of the statue

of Jupiter in the Ermitage (here Fig. 10).

This

error leads Parisi Presicce to suggest that Domitian's cult-statue of Iuppiter

Optimus Maximus Capitolinus has followed exactly the same iconography. For a

discussion; cf the Preview "Hadrian

/ Konstantin in Rom", Kapitel 6 and Kapitel 7. To both I will come

back below;

cf.

<https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Konstantin_Hadrian_Koloss_06.html>;

and

<https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Konstantin_Hadrian_Koloss_07.html>.

``Compare Oskar Waldhauer (1928, 4) for the

restorations of this statue of Jupiter in the Ermitage at St. Petersburg (here

Fig. 10):

"Erhaltung: Ergänzt von [Vincenzo] Pacetti [3.

April 1746 in Rom - 28. Juli 1820 in Rom] die

Nike in der rechten Hand erst in Leningrad hinzugefügt, Meister unbekannt; in

der Sammlung Campana hielt die Rechte den Blitz ..."´´.

Cf. supra, in vol. 3-1, p. 704; and p. 719, text, published on the

Website of the Ermitage.

``Although

Parisi Presicce (2022, 390) states that, in the case of the statue of Jupiter

in the Ermitage, "large portions of the statue are modern

restorations", he himself is unaware of the above-mentioned, only recently

observed facts. After what was said above, and because this statue of Jupiter

in St. Petersburg (hier Fig. 10) was

found in Domitian's Villa on Lago

Albano, his Albanum, I believe that

this statue was certainly a copy of the most important sculpture which Domitian

had the chance to order during his reign: his (fourth) cult-statue of Iuppiter

Optimus Maximus Capitolinus.

Cf. supra, in vol. 3-1, p. 234, in Chapter Preamble:

``Personally, I prefer the following

judgements about Domitian by other scholars : ... by Claudio Parisi Presicce,

Massimiliano Munzi and Maria Paola Del Moro (2023, 10): `"La profonda dedizione [i.e., of Domitian] per gli dei e, insieme, il sentimento religioso che lo portò a sentire

su di sé la loro protezione, soprattutto quella di Minerva, ne determinarono il comportamento di

attenta cura delle cerimonie e degli edifici sacri, la cui espressione più alta

fu la lussuosa ricostruzione del tempio capitolino arso nell'incendio dell'80

d.C. ..." [my emphasis]´´.

Let's now turn to the hypotheses concerning

Domitian's (fourth) cult-statue of Jupiter Capitolinus in detail that have been

published by Claudio Parisi Presicce (2022).

In the

Preview "Hadrian / Konstantin in

Rom", in Kapitel 4, I write:

cf.

<https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Konstantin_Hadrian_Koloss_04.html>:

``4.) Contrary to my own

opinion, published in this Study,

that the Domitianic statue of Jupiter in the Ermitage (here Fig. 10) is a copy of Domitian's

(fourth) cult-statue of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus, but ignoring the

facts concerning this statue, mentioned at the end of Kapitel 3 in the Preview "Hadrian / Konstantin in Rom"

[which have just been summarized above];

cf.

<https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Konstantin_Hadrian_Koloss_03.html>,

Claudio Parisi Presicce (2022, 390 with n. 4) believes, that the statue at the Ermitage (here Fig. 10) is either a copy of

Vespasian's (third) cult-statue of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus (which,

in my opinion, is not true), or of the (fourth) cult-statue, commissioned by

Domitian: "whose [i.e., the

statue in der Ermitage; here Fig. 10] dating to the Flavian period makes it the

finest rendering of the cult statue from the time of Vespasian or Domitian.

[With n. 4; my emphasis]".

In his note 4, Parisi Presicce provides references for the statue in the

Ermitage, inter alia: "Martin

1987, pp. 28-31, 131-144; Maderna 1988, p. 27, pl. 5.4"´´.

As

discussed in the Preview "Hadrian /

Konstantin in Rom", Kapitel 4;

cf.

<https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Konstantin_Hadrian_Koloss_04.html>,

``Claudio

Parisi Presicce (2022, 389) writes concerning Vespasian's (third) and

Domitian's (fourth) cult-statues of Jupiter Capitolinus:

"The

fire that broke out during the second year of Titus’s rule, however, is

remembered mainly for having reached the Capitoline Hill and destroyed the

ancient temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus that

had recently been restored by Vespasian, the father and progenitor of the

Flavian dynasty.

The

69 CE reconstruction of the temple -

[but see

above, in the Preview " Hadrian /

Konstantin in Rom", Kapitel 2, at point 2.);

cf.

<https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Konstantin_Hadrian_Koloss_02.html>:

correct

would be the following formulation: Vespasian's "reconstruction" of

his (third) Tempel of Jupiter Capitolinus, after the (second) temple had been

destroyed in the fire of AD 69,]

- is depicted on a series of bronze coins

minted between 71 and 79 CE [with n. 2 = here Fig. 157a, left; Fig. 157a, right] in which

Jupiter can be seen enthroned in the center of the cella. The god is seated

with his left arm raised and his hand resting on the scepter, while his right

hand is outstretched and holds an orb surmounted by Victory; his cloak

hangs from his left shoulder leaving his torso bare and is wrapped around the

lower part of his body.

The

same statuary type was also replicated by Domitian, who completed the

restoration of the Capitoline temple after his brother’s [i.e., Titus's] death on September 12, 81 CE, and

inaugurated it.

The

statue echoed the traditional archetype dating back to the Phidian sculpture of

Zeus at Olympia, [with n. 3 = here Fig.

14] which was also used as a

reference model during the reconstruction of the cult statue (a

chrysoelephantine statue attributed to the sculptor Apollonios) commissioned by

Sulla following the fire of 83 BCE, which had replaced the archaic agalma [my emphasis]".

In his note 2, Parisi Presicce writes:

"Prayon 1982, pp. 320, 327, pl. 71, 10; Maderna 1988, p. 27 and note 90

(earlier biography [corr.:

bibliography]), pl. 5, 3".

In his note 3, he writes: "Palagia

2019"´´.

According to Parisi Presicce (2022, 389),

Vespasian's (third) and Domitian's (fourth) cult-statue of Jupiter Capitolinus

were thus represented in the same iconography as the cult-statue of Zeus in his

temple at Olympia (cf. here Fig. 14).

See my

comment in the Preview "Hadrian /

Konstantin in Rom", Kapitel 4 (here translated into English);

cf.

<https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Konstantin_Hadrian_Koloss_04.html:

``Claudio Parisi Presicce's (2022, 389)

above-quoted description of Vespasian's (third) cult-statue of Jupiter

Capitolinus ist not true. In

Parisi Presicce's opinion, the god, as shown by Vespasian's bronze coins

(issued between AD 71-79 [= here Fig. 157a, left; Fig. 157a, right]), was holding with his left raised hand his sceptre,

and on his outstretched right hand a globe, surmounted by Victory.

In reality, those coins of Vespasian (here

Fig. 157a, left; Fig. 157a, right) show, that the right hand of Vespasian's

(third) cult-statue of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus was lying on his

right thigh and held the god's thunderbolt´´.

In

addition, we shall see below, in Chapter II.), when discussing Domitian's

coins (here Fig. 83), representing

his (fourth) Temple of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus, that also

Domitian's (fourth) cult-statue of Jupiter Capitolinus held with his right hand

his thunderbolt, which was lying on his right thigh.

See the

Preview "Hadrian / Konstantin in

Rom", Kapitel 5;

cf.

<https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Konstantin_Hadrian_Koloss_05.html>:

``5.) Claudio Parisi Presicce observes that the two holes in the palm

of the right hand of the colossal portrait of Constantine (here Figs. 11; 11.1; 156) allow the

conclusion that the original statue had held a different object in its right

hand than the portrait of Constantine, which has been reworked from this

statue.

See

Parisi Presicce (2006b, 151 with n. 44 [cf. supra,

in vol. 3-1, p. 753]; Parisi Presicce 2022, pp. 394-395; and p. 407, with ILL.

1, in: "46 Right hand and foot of

the Colossus of Constantine 312 CE").

Parisi

Presicce (2022, pp. 394-395) writes:

"Hans Peter L’Orange [with n. 30] offered a different interpretation,

maintaining that the reworkings are not attributable to alterations made to a

pre-Constantinian portrait, but are the result of a Christian revision of

the statue in the years 324–337 CE, which

can be deduced from the substantial retouching detectable [page 395] on the head and a possible substitution of

attributes, namely the addition of the diadem and the symbol of the cross in

place of the scepter. This seems at least partly plausible, because,

although it is not possible to prove the complete substitution of the limb, the [right] hand belonging to the Colossus [46]

has two holes of different shape and

size in the palm, probably due to the substitution or duplication of the

attribute, with the addition of the cross [my emphasis]".

In his note 30, Parisi Presicce writes:

"L’Orange 1982a, p. 163; L’Orange 1984, pp. 70–77".

Cf. H.P. L’Orange 1982a, "In

hoc signo vinces", Boreas 5

(1982) 160–163.

With

"[46]", Parisi Presicce (2022, 395) refers to the following catalogue

text: "46 Right hand and foot of the

Colossus of Constantine 312 CE ...", in: Parisi Presicce (2022, pp.

407-409).

As we

shall see in a minute, L'Orange (1982a; 1984), by mentioning a

"Kreuz" (`cross´) - an assumption, now followed by Parisi Presicce

(2022s, 395) - had referred to what Constantine the Great had himself called

"heilbringendes Zeichen" (`salvation bringing sign´). The real nature

of this sign is still unknown (see below). Besides, we have only one literary

source, in which this sign is mentioned:

The

Christian author Eusebius (Hist. Eccl.

9,9,10-11) has described an honorary statue for Constantine the Great "auf

Roms belebtestem Platz" (`on Rome's most crowded square´), as Klaus M.

Girardet (2020, 90) translates Eusebius's text (cf. supra, in vol., 3-1, p. 776), and which, according to Eusebius, the

Senate had erected in honour of Constantine's victory over Maxentius at the Pons Milvius (AD 312). Eusebius mentions

the fact that Constantine had added to this honorary statue an inscription in

Latin, which Eusebius quotes (in a Greek translation). As Eusebius reports,

Constantine writes in this text that he himself had ordered that the artists

should give his portrait-statue the (so far unidentified) `salvation bringing

sign´ in its right hand, which had brought him the victory at the Pons Milvius.

And only Claudio Parisi Presicce writes

(2006b, 140, commenting on Eusebius, Hist.

Eccl. 9,9, 10-11), that the statue of Constantine, mentioned by Eusebius,

held a globe in its left hand. This assertion of Parisi Presicces (2006b, 140)

is not true. Eusebius (Hist. Eccl. 9,9,10-11) does not say that

this portrait-statue of Constantine held a globe in its left hand.

My thanks are due to Franz Xaver Schütz who,

on 26th August 2024, after we had discussed this matter, has checked Eusebius (Hist. Eccl. 9,9, 10-11).

See for

this subject also the Preview "Hadrian

/ Konstantin in Rom", Kapitel 6;

cf.

<https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Konstantin_Hadrian_Koloss_06.html>´´.

To this I will come back below.

``Compare

for the text of Eusebius: Kirsopp Lake, Eusebius

The Ecclesiastical History with an English Translation by Kirsopp Lake in two

volumes (1926); and Philipp Haeuser, Eusebius

Caesariensis: Des Eusebius Pamphili Bischofs v. Caesarea Teil: Bd. 2.,

Kirchengeschichte / Aus dem Griechischen übers. v. Haeuser (1932).

To my great surprise, I have now realized, that

the passage `Eusebius (Hist. Eccl.

9,9,10-11)´, as quoted by Parisi Presicce (2006b, 140), ist exactly the same,

which Heinz Kähler (1960, 391, Taf. 264) has (erroneously) quoted as `Eusebius

(Hist. Eccl. 10,4,16)´. For Kähler's

translation and comments on this report by Eusebius (cf. supra, in vol. 3-1, pp. 730-731). I had, unfortunately, not checked

Kähler's (erroneous) quotation of Eusebius, and had uncritically repeated it

several times in my Study; and that,

although I had also consulted for example Helga von Heintze (1966, 253), who

has quoted this passage of Eusebius correctly: "(Hist. Eccl.

9,9,10-11)" (cf. supra, in vol.

3-1, p. 732). I am, therefore, very

glad that I am now able to correct this error (!).

For the

text of Eusebius (Hist. Eccl.

9,9,10-11) about this honorary statue of Constantine and the inscription, which

Constantine had himself added to this statue, and which Eusebius has quoted verbatim (!); cf. supra, in vol. 3-1, pp. 730-732, 734-738, 757, 758, 771-774.

776-778.

Note

that Parisi Presicce (2022, 395) uncritically repeats an error of earlier

scholars, which has long since been abandoned. According to this

interpretation, this `heilbringendes Zeichen´ (salvation bringing sign´) which,

according to Eusebius (Hist. Eccl.

9,9,10-11) Constantine had mentioned in his own inscription, which he added to

his honorary statue, may be identified with the cross. In reality, the cross

has assumed the meaning [as a `salvation bringing sign´] only in the 5th

century; cf. Helga von Heintze (1966, 252-254; cf. supra, in vol. 3-1, p. 732). Klaus M. Girardet is for example

convinced that the statue of Constantine, described by Eusebius, held "das

christianisierte Vexillum, also ein Feldzeichen" in its right hand; cf. id. (2020, 90 with n. 408, p. 93 with n.

423; cf. supra, in vol. 3-1, pp. 776,

778).

Why should we reject Parisi Presicce's (2022,

395) above-quoted hypothesis, according to which the colossal statue of Constantine (here

Figs. 11; 11.1; 156) held a cross in its right hand?

Inter alia

because the statue of Constantine, seen by Eusebius (Hist. Eccl. 9,9,10-11), was certainly not the portrait of Constantine discussed here (as, for

example, believed by C. CECCHELLI 1951; 1954, followed by H. KÄHLER 1952; 1960;

cf. supra, in vol. 3-1, pp. 730,

753-754, 757, 758). Why can we be sure about that? The statue of Constantine,

which, according to Eusebius (Hist. Eccl.

9,9,10-11), stood `on Rome's most crowded square´, cannot possibly have been

the statue of Hadrian/Constantine (here Figs.

11; 11.1; 156), because the latter is an acrolithic portrait (cf. supra, in vol. 3-1, pp. 750-752). But

there is more to consider:

The results obtained in the Preview "Hadrian / Konstantin in Rom", Kapitel 5:

a) As we have seen, only Eusebius (Hist. Eccl. 9,9,10-11) mentions a statue of Constantine in Rome,

which held in its right hand the `salvation bringing sign´, thanks to which, as

stated by Constantine himself, he had been victorious in the battle at the Pons Milvius; we have also seen that Parisi Presicce's assertion (2022, 395),

according to which this `salvation bringing sign´ should be identified with a

cross, is based on an interpretation of this passage of Eusebius, that has been

abandoned already a long time ago;

b) We have, in addition to this, seen that the statue of

Constantine, described by Eusebius (Hist.

Eccl. 9,9,10-11), was certainly not, as some earlier scholars had believed,

the colossal portrait of Hadrian/ Constantine in the Palazzo dei Conservatori,

discussed here (here Figs. 11; 11.1; 156);

c) Parisi Presicce (2006b,

140) writes that, according to Eusebius (Hist.

Eccl. 9,9, 10-11), the statue of

Constantine, described by Eusebius, held a globe in its left hand. As we

have seen above, this assertion is not true.

Claudio

Parisi Presicce's (2022) reconstruction of the colossus of Constantine in scale

1:1 (here Fig. 156), follows now -

to my great surprise - precisely that iconography, which he has postulated for

that statue of Constantine in Rome, on which Eusebius (Hist. Eccl. 9,9,10-11) has reported. This reconstruction (here Fig. 156) is obviously and explicitly

based on research (see the caption of Fig.

156), conducted by Claudio Parisi Presicce (2006b, 140; id. 2022, 395; cf. supra, at points a) and c)). Parisi Presicce's

relevant findings concern both, the colossal portrait of Hadrian/ Constantine

in the Palazzo dei Conservatori (here Fig.

11), and the statue of Constantine, described by Eusebius (Hist. Eccl. 9,9,10-11).

But there is a problem: as we have seen above,

at points a) and c), Parisi Presicce's statements concerning the iconography of the

statue of Constantine, described by Eusebius, are not correct concerning those

two important details. To the effect that the reconstruction of the colossus of

Constantine in scale 1:1 (here Fig. 156) shows the Emperor Constantine now with

a globe in his left hand; and that, although there is no ancient literary

source, or any ancient representation, on the basis of which this specific

detail of the iconography, chosen for this reconstruction of the colossus of

Constantine, could be explained.

See also

infra, the summaries of the Preview

"Hadrian / Konstantin in Rom",

Kapitel 6 and Kapitel 7;

cf.

<https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Konstantin_Hadrian_Koloss_06.html>;

and cf.

<https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Konstantin_Hadrian_Koloss_07.html>.

But against the choice of this very

iconography for the reconstruction of the colossus of Hadrian/ Constantine

(here Figs. 11; 11.1; 156) speaks still another, even more serious argument, mentioned

above, in point b): namely the fact

that this colossal statue of Hadrian/ Constantin is certainly not the statue, described by Eusebius (Hist. Eccl. 9,9,10-11)´´.

See the

Preview "Hadrian / Konstantin in

Rom", Kapitel 6;

cf.

<https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Konstantin_Hadrian_Koloss_06.html>:

``6.) The left arm and the left hand of the colossus of Hadrian/

Constantine (here Fig. 11) are not

preserved.

Compare

for this statement the following quotation from Claudio Parisi Presicce (2006b,

140; cf. supra, in vol. 3-1, p. 757),

which has already been discussed above, in the summary of the Preview "Hadrian / Konstantin in Rom",

Kapitel 5;

cf.

<https://fortvna-research.org/FORTVNA/FP3/Konstantin_Hadrian_Koloss_05.html>:

"Dello scettro [of the colossus of

Constantine here Figs. 11; 11.1; 156]

resta l’innesto nel palmo della mano

[destra]. È stato proposto che lo

scettro terminasse con una croce, come nel medaglione in argento conservato

a Monaco [with n. 13], e che la statua

coincida con quella descritta da Eusebio [with n. 14], eretta dal Senato ``a Roma nel luogo più pubblico di tutti´´ [with

n. 15]. Sappiamo che quest’ultima recava

nella mano sinistra il globo, ma del braccio sinistro del colosso marmoreo [of

the colossus of Constantine here Fig. 11] nessun frammento è conservato [my

emphasis]".

In his note 13, Parisi Presicce writes:

"A. ALFÖLDI, Das Kreuzszepter

Konstantins des Grossen, in SchwMüBl,

IV, 16, 1954, pp. 81-86". - As mentioned above, in the summary of the

Preview "Hadrian / Konstantin in